-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

M Reza, S Maeso, J A Blasco, E Andradas, Meta-analysis of observational studies on the safety and effectiveness of robotic gynaecological surgery, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 97, Issue 12, December 2010, Pages 1772–1783, https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7269

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The safety and effectiveness of robotic, open and conventional laparoscopic surgery in gynaecological surgery was assessed in a systematic review of the literature. This will enable the general surgical community to understand where robotic surgery stands in gynaecology.

A search was made for previous systematic reviews in the Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment, Cochrane Collaboration and Hayes Inc. databases. In addition, the MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL databases were searched for primary studies. The quality of studies was assessed and meta-analyses were performed.

Twenty-two studies were included in the review. All were controlled but none was randomized. The majority were retrospective with historical controls. The settings in which robotic surgery was used included hysterectomy for malignant and benign disease, myomectomy, sacrocolpopexy, fallopian tube reanastomosis and adnexectomy. Robotic surgery achieved a shorter hospital stay and less blood loss than open surgery. Compared with conventional laparoscopic surgery, robotic surgery achieved reduced blood loss and fewer conversions during the staging of endometrial cancer. No clinically significant differences were recorded for the other indications tested.

The available evidence shows that robotic surgery offers limited advantages with respect to short-term outcomes. However, the clinical outcomes should be interpreted with caution owing to the methodological quality of the studies.

Introduction

Advantages of laparoscopic surgery, such as a more rapid postoperative recovery and more acceptable cosmetic results, have been known for many years. Laparoscopy has stimulated the development of new techniques, including robotic surgery. A number of robotic surgery devices have been developed, such as the Automated Endoscopic System for Optimal Positioning (AESOP®; Computer Motion, Santa Barbara, California, USA), the Zeus Surgical System® (Computer Motion) and the Da Vinci Surgical System® (DVSS; Intuitive Surgical, Mountain View, Sunnyvale, California, USA). The DVSS is the only robotic system cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) currently on the market. In Europe, it has full regulatory clearance and the system has got the Conformité Européenne (CE) mark.

The DVSS device is an operator-directed robot that allows surgeons to work in certain areas of the body using very small incisions. Via a console, and with the aid of a stereoscopic viewer, the surgeon controls the robotic arms with hand controls and pedals. The movements of the surgeon's hands are digitalized and transmitted to the robotic arms, which make identical movements in the surgical field. These arms have joints that allow free movement comparable to that of human arms and hands. They are also fitted with an antitremble filter. The surgeon sees a three-dimensional image of the surgical field on a monitor, provided by the binocular viewer on the console. The images show the intraoperative area and the surgical instruments at the ends of the robotic arms. The movements of the robotic arms cease if the surgeon looks away from the screen1. The control console and the robotic arms are connected via a data cable. Telesurgery is possible, in which the surgeon and patient are not in the same room, although this is limited by data transfer speeds. In the USA, the FDA currently allows the use of this device only when both surgeon and patient are physically together.

Advantages of the DVSS include the potential for greater precision, lower error rates, reduced bleeding, a shorter hospital stay, more rapid patient recovery, smaller scars and reduced pain. It is said to be easier to master than conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS)2. It should be remembered, however, that the robotic arms follow the movements of the surgeon, whose experience, skill and judgement all influence the surgical results obtained. It also provides ergonomic advantages for the surgeon, although it is also reported to suffer the drawbacks of lack of tactile feedback, longer surgery times and higher costs2.

The DVSS is now used in general, urological, gynaecological and cardiothoracic surgery3. The FDA cleared its use for gynaecological procedures in April 2005, based on the results of pioneering work in which this system was used to perform myotomies4. Since then, interest in this system for use in the gynaecological setting has increased rapidly.

The safety and effectiveness of robotic surgery using the DVSS, open surgery (OS) and CLS in the gynaecological setting was assessed in a systematic review of the literature. This will help the general surgical community to understand the present status of robotic surgery in gynaecology.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken, in which the best evidence regarding the safety and effectiveness of the DVSS in the gynaecological setting was analysed. An exhaustive search was made for published systematic reviews and assessment reports in the databases of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) databases), the Cochrane Collaboration and Hayes Inc. A single systematic review of good quality that discussed the DVSS was found (published in 2004)5, from which individual studies were retrieved. In addition, primary studies published from 2003 onwards were sought in the MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL databases. No further search restrictions were imposed. The last search was performed in October 2009. The following search terms were used: Da Vinci (tw) OR Davinci (tw) OR ((robotics (MESH) OR robot* (tw)) AND surg* (tw)). The complete strategy used with each database has been published elsewhere3. A manual search was also performed using the references cited in these articles, and experts in surgery were contacted.

For inclusion, studies needed to be in humans, and to compare the DVSS with CLS or OS in a gynaecological setting. Studies without control groups were excluded, as were those involving animals or cadavers. The quality of the selected studies was assessed against a checklist6,7 that examined aspects of the methodology followed. Quality aspects were, among others, whether there was a clearly defined question, whether the study was randomized and blinded, the type of follow-up, whether there was equality in patient management, and the comparability of the groups established. A data collection form was used to record all relevant information, such as design, sample size, hospital(s) involved, type of intervention, characteristics of the technologies being compared, patient characteristics and results.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis of the results was considered when results were available from at least two studies. Significance was set at P⩽0·050. The possible clinical and statistical heterogeneity of the gathered results was first examined and meta-analysis performed only if the former was low. Statistical heterogeneity was considered high when I2 was at least 50 per cent and low when it was below 50 per cent. If high, a sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the study that contributed most to the heterogeneity, and possible differences sought between this and the remaining studies8. In meta-analysis, the fixed-effects method was used when the statistical heterogeneity was low, and the random-effects method when it was high.

For dichotomous variables, meta-analysis of odds ratios (ORs) was performed using the Mantel–Haenszel method, because the sample sizes reported in the studies were fairly small. In such analyses, if one of the studies reported no events in any treatment group, or if events were reported in all patients in all groups, meta-analysis of risk difference was performed using the same method.

For continuous variables, meta-analysis of the differences between means was performed using the inverse variance method. When subgroups had to be combined for meta-analysis, the formulas of Higgins and Green8 were used to obtain the means and joint standard deviations. When only medians were available, these were used as estimates of means8,9. When a study failed to indicate the standard deviation, this variable was calculated from the standard error of the mean, 95 per cent confidence interval, t value or the interquartile range8. Some studies only provided ranges; in such instances the standard deviation was estimated as indicated by Hozo and co-workers9 using the formula total range/4 (as long as there were 70 or fewer subjects).

Meta-analyses and graphical representation of the results were undertaken using Review Manager (RevMan) software version 5.0 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). ORs and mean differences are presented with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Results

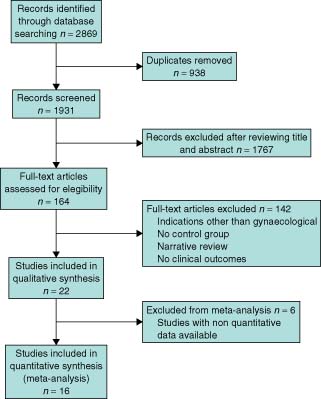

A total of 2869 potential primary studies were detected in the MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL databases. This was reduced to 1931 following the elimination of duplicates. After reading the abstracts (full text when necessary) of these studies, 22 were found to meet all the required criteria and were included in the present systematic review and sixteen of them were also included in the quantitative synthesis (Fig. 1).

Flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review

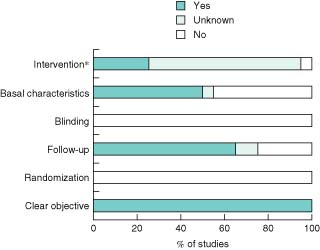

Fig. 2 summarizes features of the studies according to the quality checklist. All studies were controlled, but none was randomized. None reported a clinical trial. The majority had adequate patient follow-up and were designed on an intention-to-treat basis. Generally patients who had been diverted to another type of surgery were analysed in their original group. Approximately half of the studies described some difference in baseline characteristics between patient groups. Although information was provided regarding the intervention to which patients were subjected, the majority of studies did not specify whether patients in different groups were managed similarly in other respects. Generally, the collection of data was retrospective, and the different study groups were treated within different time periods. No information—or only that pertaining to patients who had robotic surgery—was provided regarding preoperative and postoperative care, nor were discharge criteria specified.

Quality of included studies. *Apart from the experimental intervention, groups were treated in the same way

The indications for which the DVSS was assessed in these studies included: hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer, radical hysterectomy for the treatment of cervical cancer, hysterectomy for the treatment of benign disease, myomectomy, sacrocolopexy, fallopian tube reanastomosis and adnexectomy.

Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer

Seven articles10–16 were included in which use of the DVSS was compared with OS and CLS with regard to hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer (Table 1). Two of these assessed the DVSS in a subgroup of obese patients11,16 that formed part of other studies10,15 included in the present analysis. To avoid the duplication of data from these patients, these subgroups were analysed separately.

Studies included in the review

| . | No. of patients . | . | . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference . | Total . | DVSS . | OS . | CLS . | Design . | Centre . | Intervention period . | Control period . | Surgeons . |

| Hysterectomy for the staging of | |||||||||

| endometrial cancer | |||||||||

| Boggess et al. 200810 | 322 | 103 | 138 | 81 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| Gehring et al. 200811 | 81 | 49 | — | 32 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Veljovich et al. 200812 | 160 | 25 | 131 | 4 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2005–2006 | NS |

| Bell et al. 200813 | 110 | 40 | 40 | 30 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2007 | Same |

| DeNardis et al. 200814 | 162 | 56 | 106 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | < 2006 | NS |

| Seamon et al. 200915 | 181 | 105 | — | 76 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 1998–2005 | Same |

| Seamon et al. 200916 | 300 | 109 | 191 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 1998–2006 | Different |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical | |||||||||

| cancer | |||||||||

| Sert and Abeler 200717 | 15 | 7 | — | 8 | HC | S | 2005–2006 | 2004–2005 | Same |

| Boggess et al. 200818 | 100 | 51 | 49 | — | HC | S | 2005–2007 | < 2005 | NS |

| Ko et al. 200819 | 48 | 16 | 32 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Different |

| Magrina et al. 200820 | 93 | 27 | 35 | 31 | HC | S | 2003–2006 | 1993–2006 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200821 | 43 | 13 | — | 30 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2000–2006 | NS |

| Estape et al. 200922 | 63 | 32 | 14 | 17 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2004–2006 | NS |

| Maggioni et al. 200923 | 80 | 40 | 40 | — | HC | S | 2007–2009 | < 2007 | NS |

| Hysterectomy for benign disease | |||||||||

| Payne and Dauterive 200824 | 200 | 100 | — | 100 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Same |

| Myomectomy | |||||||||

| Advincula et al. 200725 | 58 | 29 | 29 | — | P | S | 2000–2004 | 2000–2004 | Different |

| Bedient et al. 200926 | 81 | 40 | — | 41 | HC | S | 2004–2008 | 2000–2008 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200927 | 50 | 15 | — | 35 | P | S | 2006–2007 | 2006–2007 | Same |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||||||

| Rodgers et al. 200728 | 67 | 26 | 41 | — | P | S | 2001–2006 | 2001–2006 | Different |

| Dharia Patel et al. 200829 | 28 | 18 | 10 | — | HC | S | 2003–2004 | 2002–2003 | Different |

| Sacrocolpopexy | |||||||||

| Geller et al. 200830 | 178 | 73 | 105 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 2004–2008 | Different |

| Adnexectomy | |||||||||

| Magrina et al. 200931 | 176 | 85 | — | 91 | P | S | 2003–2008 | 2003–2008 | Same |

| . | No. of patients . | . | . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference . | Total . | DVSS . | OS . | CLS . | Design . | Centre . | Intervention period . | Control period . | Surgeons . |

| Hysterectomy for the staging of | |||||||||

| endometrial cancer | |||||||||

| Boggess et al. 200810 | 322 | 103 | 138 | 81 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| Gehring et al. 200811 | 81 | 49 | — | 32 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Veljovich et al. 200812 | 160 | 25 | 131 | 4 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2005–2006 | NS |

| Bell et al. 200813 | 110 | 40 | 40 | 30 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2007 | Same |

| DeNardis et al. 200814 | 162 | 56 | 106 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | < 2006 | NS |

| Seamon et al. 200915 | 181 | 105 | — | 76 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 1998–2005 | Same |

| Seamon et al. 200916 | 300 | 109 | 191 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 1998–2006 | Different |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical | |||||||||

| cancer | |||||||||

| Sert and Abeler 200717 | 15 | 7 | — | 8 | HC | S | 2005–2006 | 2004–2005 | Same |

| Boggess et al. 200818 | 100 | 51 | 49 | — | HC | S | 2005–2007 | < 2005 | NS |

| Ko et al. 200819 | 48 | 16 | 32 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Different |

| Magrina et al. 200820 | 93 | 27 | 35 | 31 | HC | S | 2003–2006 | 1993–2006 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200821 | 43 | 13 | — | 30 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2000–2006 | NS |

| Estape et al. 200922 | 63 | 32 | 14 | 17 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2004–2006 | NS |

| Maggioni et al. 200923 | 80 | 40 | 40 | — | HC | S | 2007–2009 | < 2007 | NS |

| Hysterectomy for benign disease | |||||||||

| Payne and Dauterive 200824 | 200 | 100 | — | 100 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Same |

| Myomectomy | |||||||||

| Advincula et al. 200725 | 58 | 29 | 29 | — | P | S | 2000–2004 | 2000–2004 | Different |

| Bedient et al. 200926 | 81 | 40 | — | 41 | HC | S | 2004–2008 | 2000–2008 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200927 | 50 | 15 | — | 35 | P | S | 2006–2007 | 2006–2007 | Same |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||||||

| Rodgers et al. 200728 | 67 | 26 | 41 | — | P | S | 2001–2006 | 2001–2006 | Different |

| Dharia Patel et al. 200829 | 28 | 18 | 10 | — | HC | S | 2003–2004 | 2002–2003 | Different |

| Sacrocolpopexy | |||||||||

| Geller et al. 200830 | 178 | 73 | 105 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 2004–2008 | Different |

| Adnexectomy | |||||||||

| Magrina et al. 200931 | 176 | 85 | — | 91 | P | S | 2003–2008 | 2003–2008 | Same |

DVSS, Da Vinci Surgical System®; OS, open surgery; CLS, conventional laparoscopic surgery; HC, historical controls; S, single centre; NS, not stated; M, multicentre; P, Prospective.

Studies included in the review

| . | No. of patients . | . | . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference . | Total . | DVSS . | OS . | CLS . | Design . | Centre . | Intervention period . | Control period . | Surgeons . |

| Hysterectomy for the staging of | |||||||||

| endometrial cancer | |||||||||

| Boggess et al. 200810 | 322 | 103 | 138 | 81 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| Gehring et al. 200811 | 81 | 49 | — | 32 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Veljovich et al. 200812 | 160 | 25 | 131 | 4 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2005–2006 | NS |

| Bell et al. 200813 | 110 | 40 | 40 | 30 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2007 | Same |

| DeNardis et al. 200814 | 162 | 56 | 106 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | < 2006 | NS |

| Seamon et al. 200915 | 181 | 105 | — | 76 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 1998–2005 | Same |

| Seamon et al. 200916 | 300 | 109 | 191 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 1998–2006 | Different |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical | |||||||||

| cancer | |||||||||

| Sert and Abeler 200717 | 15 | 7 | — | 8 | HC | S | 2005–2006 | 2004–2005 | Same |

| Boggess et al. 200818 | 100 | 51 | 49 | — | HC | S | 2005–2007 | < 2005 | NS |

| Ko et al. 200819 | 48 | 16 | 32 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Different |

| Magrina et al. 200820 | 93 | 27 | 35 | 31 | HC | S | 2003–2006 | 1993–2006 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200821 | 43 | 13 | — | 30 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2000–2006 | NS |

| Estape et al. 200922 | 63 | 32 | 14 | 17 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2004–2006 | NS |

| Maggioni et al. 200923 | 80 | 40 | 40 | — | HC | S | 2007–2009 | < 2007 | NS |

| Hysterectomy for benign disease | |||||||||

| Payne and Dauterive 200824 | 200 | 100 | — | 100 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Same |

| Myomectomy | |||||||||

| Advincula et al. 200725 | 58 | 29 | 29 | — | P | S | 2000–2004 | 2000–2004 | Different |

| Bedient et al. 200926 | 81 | 40 | — | 41 | HC | S | 2004–2008 | 2000–2008 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200927 | 50 | 15 | — | 35 | P | S | 2006–2007 | 2006–2007 | Same |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||||||

| Rodgers et al. 200728 | 67 | 26 | 41 | — | P | S | 2001–2006 | 2001–2006 | Different |

| Dharia Patel et al. 200829 | 28 | 18 | 10 | — | HC | S | 2003–2004 | 2002–2003 | Different |

| Sacrocolpopexy | |||||||||

| Geller et al. 200830 | 178 | 73 | 105 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 2004–2008 | Different |

| Adnexectomy | |||||||||

| Magrina et al. 200931 | 176 | 85 | — | 91 | P | S | 2003–2008 | 2003–2008 | Same |

| . | No. of patients . | . | . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference . | Total . | DVSS . | OS . | CLS . | Design . | Centre . | Intervention period . | Control period . | Surgeons . |

| Hysterectomy for the staging of | |||||||||

| endometrial cancer | |||||||||

| Boggess et al. 200810 | 322 | 103 | 138 | 81 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| Gehring et al. 200811 | 81 | 49 | — | 32 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2004 | NS |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Veljovich et al. 200812 | 160 | 25 | 131 | 4 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2005–2006 | NS |

| Bell et al. 200813 | 110 | 40 | 40 | 30 | HC | S | 2005–2007 | 2000–2007 | Same |

| DeNardis et al. 200814 | 162 | 56 | 106 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | < 2006 | NS |

| Seamon et al. 200915 | 181 | 105 | — | 76 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 1998–2005 | Same |

| Seamon et al. 200916 | 300 | 109 | 191 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 1998–2006 | Different |

| (obese patients) | |||||||||

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical | |||||||||

| cancer | |||||||||

| Sert and Abeler 200717 | 15 | 7 | — | 8 | HC | S | 2005–2006 | 2004–2005 | Same |

| Boggess et al. 200818 | 100 | 51 | 49 | — | HC | S | 2005–2007 | < 2005 | NS |

| Ko et al. 200819 | 48 | 16 | 32 | — | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Different |

| Magrina et al. 200820 | 93 | 27 | 35 | 31 | HC | S | 2003–2006 | 1993–2006 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200821 | 43 | 13 | — | 30 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2000–2006 | NS |

| Estape et al. 200922 | 63 | 32 | 14 | 17 | HC | S | 2006–2008 | 2004–2006 | NS |

| Maggioni et al. 200923 | 80 | 40 | 40 | — | HC | S | 2007–2009 | < 2007 | NS |

| Hysterectomy for benign disease | |||||||||

| Payne and Dauterive 200824 | 200 | 100 | — | 100 | HC | S | 2006–2007 | 2004–2006 | Same |

| Myomectomy | |||||||||

| Advincula et al. 200725 | 58 | 29 | 29 | — | P | S | 2000–2004 | 2000–2004 | Different |

| Bedient et al. 200926 | 81 | 40 | — | 41 | HC | S | 2004–2008 | 2000–2008 | NS |

| Nezhat et al. 200927 | 50 | 15 | — | 35 | P | S | 2006–2007 | 2006–2007 | Same |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||||||

| Rodgers et al. 200728 | 67 | 26 | 41 | — | P | S | 2001–2006 | 2001–2006 | Different |

| Dharia Patel et al. 200829 | 28 | 18 | 10 | — | HC | S | 2003–2004 | 2002–2003 | Different |

| Sacrocolpopexy | |||||||||

| Geller et al. 200830 | 178 | 73 | 105 | — | HC | M | 2006–2008 | 2004–2008 | Different |

| Adnexectomy | |||||||||

| Magrina et al. 200931 | 176 | 85 | — | 91 | P | S | 2003–2008 | 2003–2008 | Same |

DVSS, Da Vinci Surgical System®; OS, open surgery; CLS, conventional laparoscopic surgery; HC, historical controls; S, single centre; NS, not stated; M, multicentre; P, Prospective.

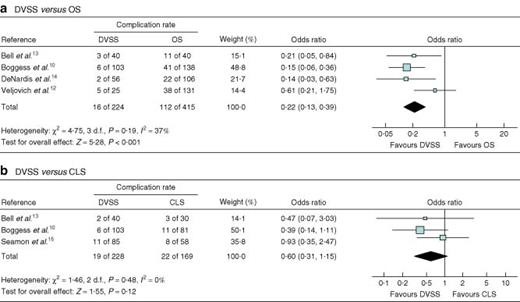

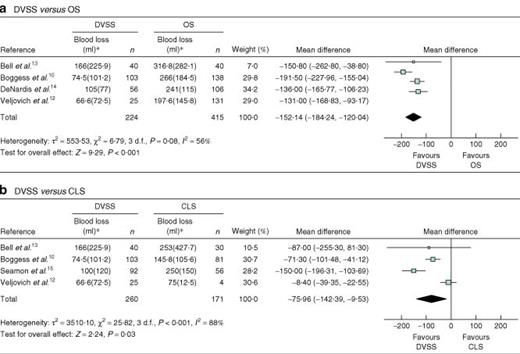

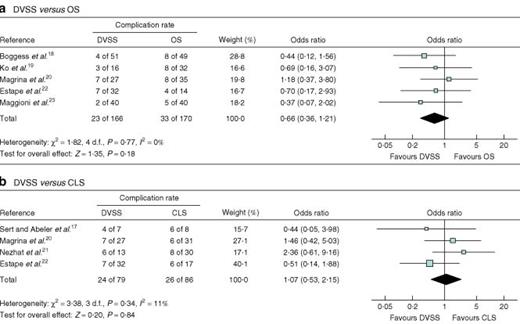

Four studies10,12–14 compared the DVSS with OS. Meta-analysis showed the DVSS to be significantly associated with a shorter hospital stay, a smaller risk of complications (Fig. 3a), reduced blood loss during surgery (Fig. 4a), a reduction in the need for transfusion, and a greater number of resected lymph nodes. However, it was associated with a longer duration of operation (by a mean of 89·25 min) and a greater risk of needing to convert to another surgical method (OR 11·54, 1·40 to 94·97) (Table 2).

Forest plots showing meta-analysis of complications associated with hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer: a robotic surgery using the Da Vinci Surgical System® (DVSS) versus open surgery (OS) and b DVSS versus conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS). A Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effects method was used. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Forest plots showing meta-analysis of blood loss associated with hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer: a robotic surgery using the Da Vinci Surgical System® (DVSS) versus open surgery (OS) and b DVSS versus conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS). An inverse variance random-effects method was used. *Values are mean(s.d.). Mean differences are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Meta-analysis results: Da Vinci Surgical System®versus open surgery

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 93 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·68 (−3·53, − 1·84) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 56 | MD (IV, REM) | − 152·14 (−184·24, − 120·04) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12–14 | 639 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | 5·91 (0·13, 11·68) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·92 (−3·02, 12·86) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·43 (−4·49, 13·15) |

| Complications (%) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 37 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·22 (0·13, 0·39) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,14 | 483 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·25 (0·07, 0·81) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,14 | 403 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 11·54 (1·40, 94·97) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 95 | MD (IV, REM) | 89·25 (51·69, 126·81) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·05 (−2·80, − 1·29) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | − 334·17 (−459·44, − 208·91) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 86 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·29 (−4·16, 6·73) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·18 (0·07, 0·44) |

| Complications (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·66 (0·36, 1·21) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 219,20 | 110 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·05, 0·05) |

| Positive margins (%) | 219,22 | 94 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·58 (0·14, 2·33) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 31·39 (−10·33, 73·11) |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·64 (−1·86, 0·58) |

| Complications (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 3 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·41 (0·08, 2·06) |

| Time to return to work (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, REM) | − 15·97 (−19·55, − 12·38) |

| Pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·86 (0·37, 1·99) |

| Miscarriages (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·37 (0·11, 1·20) |

| Ectopic pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·13 (0·30, 4·33) |

| Intrauterine pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 44 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·99 (0·74, 5·36) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | 46·85 (34·66, 59·04) |

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 93 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·68 (−3·53, − 1·84) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 56 | MD (IV, REM) | − 152·14 (−184·24, − 120·04) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12–14 | 639 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | 5·91 (0·13, 11·68) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·92 (−3·02, 12·86) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·43 (−4·49, 13·15) |

| Complications (%) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 37 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·22 (0·13, 0·39) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,14 | 483 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·25 (0·07, 0·81) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,14 | 403 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 11·54 (1·40, 94·97) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 95 | MD (IV, REM) | 89·25 (51·69, 126·81) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·05 (−2·80, − 1·29) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | − 334·17 (−459·44, − 208·91) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 86 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·29 (−4·16, 6·73) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·18 (0·07, 0·44) |

| Complications (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·66 (0·36, 1·21) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 219,20 | 110 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·05, 0·05) |

| Positive margins (%) | 219,22 | 94 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·58 (0·14, 2·33) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 31·39 (−10·33, 73·11) |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·64 (−1·86, 0·58) |

| Complications (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 3 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·41 (0·08, 2·06) |

| Time to return to work (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, REM) | − 15·97 (−19·55, − 12·38) |

| Pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·86 (0·37, 1·99) |

| Miscarriages (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·37 (0·11, 1·20) |

| Ectopic pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·13 (0·30, 4·33) |

| Intrauterine pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 44 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·99 (0·74, 5·36) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | 46·85 (34·66, 59·04) |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

MD, mean difference; IV, inverse variance; REM, random-effects method; OR, odds ratio; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; FEM, fixed-effects method; RD, risk difference.

Meta-analysis results: Da Vinci Surgical System®versus open surgery

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 93 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·68 (−3·53, − 1·84) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 56 | MD (IV, REM) | − 152·14 (−184·24, − 120·04) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12–14 | 639 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | 5·91 (0·13, 11·68) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·92 (−3·02, 12·86) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·43 (−4·49, 13·15) |

| Complications (%) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 37 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·22 (0·13, 0·39) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,14 | 483 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·25 (0·07, 0·81) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,14 | 403 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 11·54 (1·40, 94·97) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 95 | MD (IV, REM) | 89·25 (51·69, 126·81) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·05 (−2·80, − 1·29) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | − 334·17 (−459·44, − 208·91) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 86 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·29 (−4·16, 6·73) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·18 (0·07, 0·44) |

| Complications (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·66 (0·36, 1·21) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 219,20 | 110 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·05, 0·05) |

| Positive margins (%) | 219,22 | 94 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·58 (0·14, 2·33) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 31·39 (−10·33, 73·11) |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·64 (−1·86, 0·58) |

| Complications (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 3 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·41 (0·08, 2·06) |

| Time to return to work (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, REM) | − 15·97 (−19·55, − 12·38) |

| Pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·86 (0·37, 1·99) |

| Miscarriages (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·37 (0·11, 1·20) |

| Ectopic pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·13 (0·30, 4·33) |

| Intrauterine pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 44 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·99 (0·74, 5·36) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | 46·85 (34·66, 59·04) |

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 93 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·68 (−3·53, − 1·84) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 56 | MD (IV, REM) | − 152·14 (−184·24, − 120·04) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12–14 | 639 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | 5·91 (0·13, 11·68) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·92 (−3·02, 12·86) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,14 | 403 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | 4·43 (−4·49, 13·15) |

| Complications (%) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 37 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·22 (0·13, 0·39) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,14 | 483 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·25 (0·07, 0·81) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,14 | 403 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 11·54 (1·40, 94·97) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12–14 | 639 | 95 | MD (IV, REM) | 89·25 (51·69, 126·81) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | − 2·05 (−2·80, − 1·29) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 90 | MD (IV, REM) | − 334·17 (−459·44, − 208·91) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 86 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·29 (−4·16, 6·73) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·18 (0·07, 0·44) |

| Complications (%) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·66 (0·36, 1·21) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 219,20 | 110 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·05, 0·05) |

| Positive margins (%) | 219,22 | 94 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·58 (0·14, 2·33) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 518–20,22,23 | 336 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 31·39 (−10·33, 73·11) |

| Fallopian tube reanastomosis | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 98 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·64 (−1·86, 0·58) |

| Complications (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 3 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·41 (0·08, 2·06) |

| Time to return to work (days) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, REM) | − 15·97 (−19·55, − 12·38) |

| Pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·86 (0·37, 1·99) |

| Miscarriages (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·37 (0·11, 1·20) |

| Ectopic pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·13 (0·30, 4·33) |

| Intrauterine pregnancies (%) | 228,29 | 82 | 44 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·99 (0·74, 5·36) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 228,29 | 95 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | 46·85 (34·66, 59·04) |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

MD, mean difference; IV, inverse variance; REM, random-effects method; OR, odds ratio; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; FEM, fixed-effects method; RD, risk difference.

One study compared the DVSS with OS for this indication in obese women (BMI at least 30 kg/m2)16. No differences were seen with respect to an adequate lymphadenectomy (at least ten lymph nodes resected). However, after adjusting for co-morbidities, history of previous surgery and preoperative stage of disease, use of the DVSS made an adequate lymphadenectomy less probable (OR 0·22, 0·05 to 0·90). Patients whose procedure had to be converted to open surgery (16 per cent) were not included in the analysis. Use of the DVSS was also associated with reduced blood loss during surgery (mean 109 versus 394 ml; P < 0·001) and a reduced need for blood transfusion (OR 0·22, 0·05 to 0·97). Although operating times were longer with the robot, the hospital stay was 2 days shorter and the risk of complications smaller (OR 0·29, 0·13 to 0·65). The differences with respect to the last three variables were all significant.

Four studies10,12,13,15 compared the DVSS with CLS (Table 3). Use of the robot was associated with significantly reduced blood loss during surgery: mean difference − 75·96 (−142·39 to − 9·53) ml (Fig. 4b). The need for a blood transfusion was also reduced with the DVSS (OR 0·24, 0·09 to 0·64) and hospital stay was shorter: mean difference − 0·17 (−0·28 to − 0·06) days. In addition, the risk of conversion to another type of surgery was smaller with the DVSS (OR 0·43, 0·21 to 0·85). The overall risk of complications was not significantly different (Fig. 3b). The duration of operation varied between the studies, with no significant differences apparent between the DVSS and CLS.

Meta-analysis of results: Da Vinci Surgical System®versus conventional laparoscopic surgery

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 45 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 0·17 (−0·28, − 0·06) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 88 | MD (IV, REM) | − 75·96 (−142·39, − 9·53) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12,13,15 | 464 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·12 (−3·59, 5·83) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 75 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·89 (−3·11, 4·90) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 97 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·32 (−4·24, 8·89) |

| Complications (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·60 (0·31, 1·15) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·24 (0·09, 0·64) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,15 | 365 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·43 (0·21, 0·85) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 85 | MD (IV, REM) | − 5·83 (−29·29, 17·63) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 320–22 | 150 | 51 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·52 (−1·24, 0·21) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 320–22 | 150 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 63·52 (−100·49, − 26·54) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 320–22 | 150 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·73 (−8·39, 13·85) |

| Need to convert to open surgery (%) | 320–22 | 116 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | − 0·02 (−0·09, 0·05) |

| Total complications (%) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 11 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·07 (0·53, 2·15) |

| Recurrences (%) | 220,21 | 101 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·06, 0·06) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 220,22 | 107 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 2·46 (0·25, 24·36) |

| Positive margins (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·84 (0·20, 3·42) |

| Mortality (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·07, 0·07) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 68 | MD (IV, REM) | − 14·01 (−42·85, 14·82) |

| Myomectomy | |||||

| Blood loss (ml) | 226,27 | 130 | 44 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 72·36 (−133·22, − 11·50) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 226,27 | 131 | 79 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·18 (−54·42, 54·79) |

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 45 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 0·17 (−0·28, − 0·06) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 88 | MD (IV, REM) | − 75·96 (−142·39, − 9·53) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12,13,15 | 464 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·12 (−3·59, 5·83) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 75 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·89 (−3·11, 4·90) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 97 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·32 (−4·24, 8·89) |

| Complications (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·60 (0·31, 1·15) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·24 (0·09, 0·64) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,15 | 365 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·43 (0·21, 0·85) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 85 | MD (IV, REM) | − 5·83 (−29·29, 17·63) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 320–22 | 150 | 51 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·52 (−1·24, 0·21) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 320–22 | 150 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 63·52 (−100·49, − 26·54) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 320–22 | 150 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·73 (−8·39, 13·85) |

| Need to convert to open surgery (%) | 320–22 | 116 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | − 0·02 (−0·09, 0·05) |

| Total complications (%) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 11 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·07 (0·53, 2·15) |

| Recurrences (%) | 220,21 | 101 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·06, 0·06) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 220,22 | 107 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 2·46 (0·25, 24·36) |

| Positive margins (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·84 (0·20, 3·42) |

| Mortality (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·07, 0·07) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 68 | MD (IV, REM) | − 14·01 (−42·85, 14·82) |

| Myomectomy | |||||

| Blood loss (ml) | 226,27 | 130 | 44 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 72·36 (−133·22, − 11·50) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 226,27 | 131 | 79 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·18 (−54·42, 54·79) |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. MD, mean difference; IV, inverse variance; REM, random-effects method; OR, odds ratio; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; FEM, fixed-effects method; RD, risk difference.

Meta-analysis of results: Da Vinci Surgical System®versus conventional laparoscopic surgery

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 45 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 0·17 (−0·28, − 0·06) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 88 | MD (IV, REM) | − 75·96 (−142·39, − 9·53) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12,13,15 | 464 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·12 (−3·59, 5·83) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 75 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·89 (−3·11, 4·90) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 97 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·32 (−4·24, 8·89) |

| Complications (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·60 (0·31, 1·15) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·24 (0·09, 0·64) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,15 | 365 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·43 (0·21, 0·85) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 85 | MD (IV, REM) | − 5·83 (−29·29, 17·63) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 320–22 | 150 | 51 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·52 (−1·24, 0·21) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 320–22 | 150 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 63·52 (−100·49, − 26·54) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 320–22 | 150 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·73 (−8·39, 13·85) |

| Need to convert to open surgery (%) | 320–22 | 116 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | − 0·02 (−0·09, 0·05) |

| Total complications (%) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 11 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·07 (0·53, 2·15) |

| Recurrences (%) | 220,21 | 101 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·06, 0·06) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 220,22 | 107 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 2·46 (0·25, 24·36) |

| Positive margins (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·84 (0·20, 3·42) |

| Mortality (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·07, 0·07) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 68 | MD (IV, REM) | − 14·01 (−42·85, 14·82) |

| Myomectomy | |||||

| Blood loss (ml) | 226,27 | 130 | 44 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 72·36 (−133·22, − 11·50) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 226,27 | 131 | 79 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·18 (−54·42, 54·79) |

| Outcome . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | I2 (%) . | Statistical method . | Estimate of effect* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 45 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 0·17 (−0·28, − 0·06) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 88 | MD (IV, REM) | − 75·96 (−142·39, − 9·53) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 410,12,13,15 | 464 | 80 | MD (IV, REM) | 1·12 (−3·59, 5·83) |

| No. of pelvic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 75 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·89 (−3·11, 4·90) |

| No. of aortic lymph nodes resected | 210,15 | 365 | 97 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·32 (−4·24, 8·89) |

| Complications (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·60 (0·31, 1·15) |

| Transfusions (%) | 310,13,15 | 397 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·24 (0·09, 0·64) |

| Need to convert to another type of surgery (%) | 210,15 | 365 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·43 (0·21, 0·85) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 410,12,13,15 | 431 | 85 | MD (IV, REM) | − 5·83 (−29·29, 17·63) |

| Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 320–22 | 150 | 51 | MD (IV, REM) | − 0·52 (−1·24, 0·21) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 320–22 | 150 | 0 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 63·52 (−100·49, − 26·54) |

| No. of lymph nodes resected | 320–22 | 150 | 94 | MD (IV, REM) | 2·73 (−8·39, 13·85) |

| Need to convert to open surgery (%) | 320–22 | 116 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | − 0·02 (−0·09, 0·05) |

| Total complications (%) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 11 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 1·07 (0·53, 2·15) |

| Recurrences (%) | 220,21 | 101 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·06, 0·06) |

| Transfusion required (%) | 220,22 | 107 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 2·46 (0·25, 24·36) |

| Positive margins (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | OR (M–H, FEM) | 0·84 (0·20, 3·42) |

| Mortality (%) | 221,22 | 92 | 0 | RD (M–H, FEM) | 0·00 (−0·07, 0·07) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 417,20–22 | 165 | 68 | MD (IV, REM) | − 14·01 (−42·85, 14·82) |

| Myomectomy | |||||

| Blood loss (ml) | 226,27 | 130 | 44 | MD (IV, FEM) | − 72·36 (−133·22, − 11·50) |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 226,27 | 131 | 79 | MD (IV, REM) | 0·18 (−54·42, 54·79) |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. MD, mean difference; IV, inverse variance; REM, random-effects method; OR, odds ratio; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; FEM, fixed-effects method; RD, risk difference.

One study11 analysed the results of a subgroup of obese or morbidly obese patients, noting that use of the robot was significantly associated with a shorter operating time, reduced blood loss and a larger number of lymph nodes resected.

Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer

Seven studies17–23 compared the DVSS with CLS or OS in the setting of radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer (Table 1).

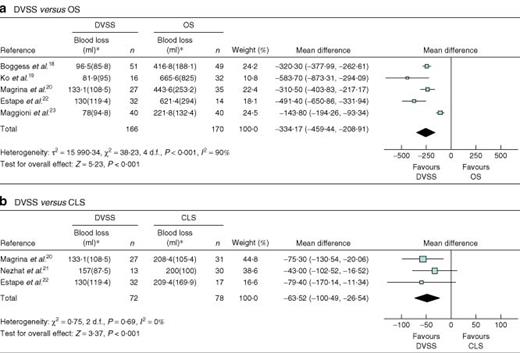

Five studies18–20,22,23 compared the DVSS with OS (Table 2). Use of the DVSS was associated with a significantly shorter hospital stay (mean difference − 2·05 (−2·80 to − 1·29) days), reduced blood loss during surgery (mean difference − 334·17 (−459·44 to − 208·91) ml) (Fig. 5a) and a reduced need for blood transfusion (OR 0·18, 0·07 to 0·44). No significant differences were seen with respect to duration of operation, number of lymph nodes resected, rate of positive margins, the proportion of patients with complications (Fig. 6a) or the need to resort to another type of surgery.

Forest plots showing meta-analysis of blood loss associated with radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a robotic surgery using the Da Vinci Surgical System® (DVSS) versus open surgery (OS) and b DVSS versus conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS). An inverse variance random-effects method was used in a and inverse variance fixed-effects method in b. *Values are mean(s.d.). Mean differences are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Forest plots showing meta-analysis of complications associated with radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a robotic surgery using the Da Vinci Surgical System® (DVSS) versus open surgery (OS) and b DVSS versus conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS). A Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effects method was used. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

One study22 reported mid-term clinical efficacy data, and found that 31 of 32 patients who a robotic procedure were alive and free from disease after a mean follow-up of 284·2 days, compared with 12 of 14 who underwent OS after a mean of 1382·4 days. This difference was not significant but follow-up times were far from comparable.

Four studies17,20–22 compared the DVSS and CLS for this indication (Table 3). Use of the robot was associated with reduced blood loss during surgery: mean difference − 63·52 (−100·49 to − 26·54) ml (Fig. 5b). The four studies yielded different results with respect to duration of operation. Surgery with the DVSS required an extra 5 or 12 min compared with CLS21,22, or 31 or 59 min less20,17. Meta-analysis showed there to be no significant difference. Three studies20,21,17 reported a shorter hospital stay with a robotic procedure (0·9, 1·1 and 4 days respectively), whereas one22 noted a longer stay (0·3 days). Meta-analysis showed no significant difference in length of stay (Table 3). Nor were there significant differences in number of lymph nodes resected, the need for conversion to another type of surgery or the proportion of patients with complications (Fig. 6b).

No study reported recurrences in either group after 1 year of follow-up. One study22 reported that 31 of 32 patients who had a robotic procedure were alive and disease free after a mean follow-up of 284·2 days compared with all 17 who had CLS after a mean follow-up of 941·6 days. The difference was not significant, but again follow-up times were not comparable.

Hysterectomy for benign disease

One large study24 compared the DVSS with CLS for this indication. Overall the duration of operation was 27 min longer for robotic surgery (P < 0·001), but 13 min shorter when only the last 25 procedures performed were included in the analysis (P = 0·03). The DVSS reduced hospital stay by 0·5 days (P = 0·007) and blood loss by 52 ml (P < 0·001).

Myomectomy

Three studies25–27 compared the results for myomectomy performed by means of the DVSS, OS and CLS for the treatment of symptomatic leiomyoma (Table 1).

One study25 compared robotic surgery with OS for this indication. With use of the DVSS the duration of operation was 80 min longer (P < 0·001), but hospital stay was 2 days shorter (P < 0·001). Blood loss was reduced by 170 ml (P = 0·011). However, the DVSS was associated with an increase in costs of US $ 18 000 (P < 0·001).

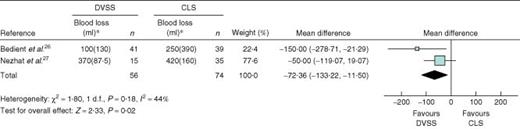

Two studies26,27 compared the DVSS with CLS for this indication (Table 1). In both studies robotic surgery was associated with reduced blood loss: mean difference − 72·36 (−133·22 to − 11·50) ml (Fig. 7, Table 3). The results for duration of operation were conflicting. One study26 reported that the DVSS procedure took 25 min less (not significant), whereas the other27 found that it took 31 min longer (P < 0·03). Other variables showed no significant difference (Table 3).

Forest plot showing meta-analysis of blood loss associated with myomectomy: robotic surgery using the Da Vinci Surgical System® (DVSS) versus conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS). An inverse variance fixed-effects method was used. *Values are mean(s.d.). Mean differences are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Fallopian tube reanastomosis

Two studies28,29 compared a robotic procedure with OS (laparotomy or minilaparotomy) for fallopian tube reanastomosis (Table 1). The results for laparotomy and minilaparotomy are pooled here unless stated otherwise.

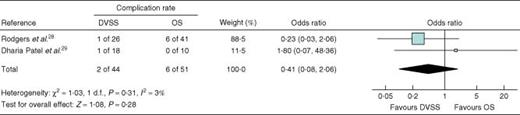

Use of the DVSS was associated with a significantly longer duration of operation, a shorter time to return to work (16 days fewer) and less consumption of analgesics. No significant differences were seen in hospital stay, the proportion of patients with complications (Fig. 8), the pregnancy rate, and the proportion of miscarriages, ectopic and intrauterine pregnancies (Table 2). One study28 reported blood loss to be similar between DVSS procedures and minilaparotomies. The same study reported that use of the DVSS was associated with a significant extra cost of US $ 1446. The other (comparing robotic surgery and laparotomy)29 indicated that the robot was associated with an overall increase in costs of US $ 2000, plus an extra US $ 300 for each newborn.

Forest plot showing meta-analysis of complications associated with fallopian tube reanastomosis: robotic surgery using the Da Vinci Surgical System® (DVSS) versus open surgery (OS). A Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effects method was used. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Sacrocolpopexy

One study30 compared use of the DVSS and abdominal sacrocolpopexy (an open procedure) in the treatment of advanced vaginal vault prolapse. The robotic procedure was associated with reduced blood loss during surgery (mean(s.d.) 103(93) versus 255(155) ml; P < 0·001) and a shorter hospital stay (1·3(0·8) versus 2·7(1·4) days; P < 0·001). The duration of surgery was longer with the robot (328(55) versus 225(61) min; P < 0·001). A small proportion of patients in the DVSS group had postoperative fever, but none after conventional sacrocolpopexy (4 versus 0 per cent; P < 0·04).

Adnexectomy

One study31 compared the DVSS with CLS for adnexectomy in 176 patients with adnexal masses. The only significant difference between the two procedures was in the duration of surgery, although this difference was a mere 12 min.

Discussion

The DVSS, being minimally invasive, achieves better short-term surgical results than OS, mainly expressed in reduced blood loss and a smaller risk of transfusion. Long-term results of hysterectomy have been reported incidentally. No differences were seen between the DVSS and OS with respect to the proportion of patients with complications, except that a robotic procedure was associated with fewer complications in hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer. Hospital stay was shorter with use of the DVSS for all indications. By and large, the duration of operation was much longer with the DVSS except in radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. During hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer more lymph nodes were resected when the robot was used. No differences in lymph node resection were found in radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. In fallopian tube reanastomosis, similar numbers of pregnancies, miscarriages, ectopic and intrauterine pregnancies were recorded.

No good cost–benefit assessment was found regarding use of the DVSS. Although the results obtained show that, compared with OS, the DVSS can provide patients with certain short-term benefits, no rigorous information was available on the extra cost of these benefits.

In hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer, radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer and hysterectomy for benign disease, use of the DVSS was also associated with some significant short-term benefits compared with CLS. Differences between robotic procedures and CLS were seen in blood loss and hospital stay, but these were not substantial (50–70 ml and 0·5 days respectively) and certainly of little importance clinically. The DVSS and CLS were also equivalent in terms of safety. Operating times varied greatly, but were comparable overall between the two groups. In hysterectomy for the staging of endometrial cancer the differences in bleeding between robotic procedures and CLS was more pronounced, conversions were fewer with the robot and complication rates were comparable.

Although economic assessments are lacking, robotic surgery might be expected to be associated with higher costs. Acquisition, use and maintenance costs for the system are all high. Cost-effectiveness data are needed in settings where the DVSS was associated with reduced blood loss. From a clinical point of view, the benefit of robotic surgery is limited. Therefore, if the costs needed to achieve this are large, use of the DVSS may not be justifiable. Moreover, published studies mostly reported perioperative and short-term postoperative results. Very little information was provided with respect to comparison of long-term results of robotic procedures versus OS or CLS in different indications. Longer-term studies are needed to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of the DVSS.

Bias is a problem to consider given the design of the studies examined. None of the studies was blinded. Nineteen of 22 studies had a historical control group. Many were of retrospective design, and the selection of patients was not discussed. The use of historical controls is hampered by the fact that patient care, other than the treatments under examination, may have changed over time, influencing the final results obtained. None of the studies discussed postoperative care or discharge criteria. Differences in patient care may have been responsible for observed differences in hospital stay, blood loss and transfusions. A more rigorous study design is needed to control these sources of bias. In addition, a high degree of heterogeneity was seen for many variables examined in the meta-analysis, which could not by and large be explained by methodological differences.

When interpreting the results it should also be remembered that use of the DVSS is associated with a period of learning. The values of certain variables, such as the duration of surgery, vary over time as the number of times a procedure is performed increases and experience is gained. Results from the first few procedures ever performed by a surgical team are likely to be different from those undertaken when the team has gained experience. In addition, teams that undertake research and publish results will have more experience or greater skill, and their results may be better than those of others. Finally, publication bias may push towards studies reporting significant differences, which normally leads to an overestimation of the differences between techniques.

Another limitation of the present review is that only controlled studies were included. The exclusion of case series leads to loss of information that might have allowed analysis of the DVSS learning curve. The exclusion of such studies also means that information regarding the safety of the technique may not have been included. Some possible advantages of the DVSS, such as better ergonomics and improvement of the surgeon's skills in general, were not assessed.

The evidence reviewed shows that robotic surgery offers certain advantages with respect to short-term outcomes compared to the classical surgical techniques. Robotic surgery with the DVSS is still evolving and is unlikely to replace OS or even CLS in gynaecology in the near future. Further studies are needed in different indications to weigh the benefits including clinical outcomes, long-term results, drawbacks and costs.

Acknowledgements

This report was supported financially with public funds. It is based on a Health Technology Assessment report financed by the Spanish Ministry of Health. The document was prepared within the collaborative framework of the Quality Plan for the National Health System produced by the Ministry of Health and Social Policy, under an agreement between the Carlos III Institute of Health, the Ministry of Science and Innovation, and the Laín Entralgo Agency. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Author notes

[Correction added after online publication 14 October 2010: the article type Systematic review was corrected to Meta-analysis]

- hemorrhage

- cervical cancer

- endometrial cancer

- gynecologic surgical procedures

- gynecology

- hysterectomy

- medline

- safety

- surgical procedures, operative

- surgery specialty

- treatment outcome

- laparoscopic surgery

- uterine myomectomy

- fallopian tube reanastomosis

- hysterectomy, radical

- cochrane collaboration

- general surgery

- community

- robotic surgery

- sacrocolpopexy

- embase