Abstract

Objectives

Cancer screening has become common in Japan. However, little is known about the socioeconomic factors affecting cancer screening participation. This study was performed to examine the association between socioeconomic status and cancer screening participation in Japanese males.

Methods

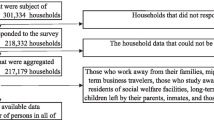

Using the data of 23,394 males sampled from across Japan, the associations between self-reported participation in screenings for three types of cancer (i.e., stomach, lung and colon) and socioeconomic variables, including marital status, types of residential area (metropolitan/nonmetropolitan), household income, and employment status, were examined using multilevel logistic regression by age group (40 to 64 and ≥65 years).

Results

The cancer screening participation rates were 34.5% (stomach), 21.3% (lung), and 24.8% (colon) for the total population studied. Being married, living in a nonmetropolitan area, having a higher income and being employed in a large-scale company showed independent associations with a higher rate of cancer screening participation for all three types of cancer. Income-related differences in cancer screening were more pronounced in the middle-aged population than in the elderly population, and in metropolitan areas than in nonmetropolitan areas.

Conclusions

There are notable socioeconomic differences in cancer screening participation in Japan. To promote cancer screening, socioeconomic factors should be considered, particularly for middle-aged and urban residents.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acheson D. Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health. London: Stationary Office; 2000.

Kogenvinas M, Pearce N, Susser M, Boffetta P. Social Inequalities and Cancer. Oxford: IARC; 1997.

Davey Smith G. Health Inequalities. Bristol: Policy Press; 2003.

Hsia J, Kemper E, Kiefe C, Zapka J, Sofaer S, Pettinger M, et al. The importance of health insurance as a determinant of cancer screening: evidence from the Women’s Health Initiative. Prev Med. 2003; 31: 261–270.

Wu ZH, Black SA, Markides KS. Prevalence and associated factors of cancer screening: why are so many older Mexican American women never screened? Prev Med. 2003; 33: 268–273.

Klassen AC, Smith ALM, Meissner HI, Zabora J, Curbow B, Mandelblatt J. If we gave away mammograms, who would get them? A neighborhood evaluation of a no-cost breast cancer screening programme. Prev Med. 2002; 34: 13–21.

Banks E, Beral V, Cameron R, Hogg A, Langley N, Barnes I, et al. Comparison of various characteristics of women who do and do not attend for breast cancer screening. Breast Can Res. 2002; 4: R1.

Lorant V, Boland B, Humblet P, Deliege D. Equity in prevention and health care. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002; 56: 510–516.

Baker D, Middleton E. Cervical screening and health inequality in England in the 1990s. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003; 57: 417–423.

Suarez L, Ramirez AG, Villarreal R, Marti J, McAlister A, Talavera GA, et al. Social networks and cancer screening in four U.S. Hispanic groups. Am J Prev Med. 2000; 19: 47–52.

Hisamichi S. Community screening programmes of cancer and cardiovascular diseases in Japan. J Epidemiol. 1996; 6: S159-S163.

Yamaguchi K. Overview of cancer control programmes in Japan. Jpn J Oncol. 2002; 32: S22-S31. (Article in Japanese)

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report of Community and Elderly Health. Tokyo: Health and Welfare Statistics Association; 2003. (Article in Japanese)

Yoshimura T. Occupational health. J Epidemiol. 1996; 6: S115-S120.

Hamashima C, Yoshida K. What is important for the introduction of cancer screening in the workplace? Asia Pac J Can Prev. 2003; 4: 39–43.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2001 Comprehensive Survey of the Living Conditions of People on Health and Welfare. Tokyo: Health and Welfare Statistics Association; 2003. (Article in Japanese)

Mejer L, Siermann C. Income Poverty in the European Union: Children, Gender and Poverty Gaps. Luxembourg: Eurostat; 2000.

Hirata M, Kumagai S, Tabuchi T, Tainaka H, Ando T, Orita H. Actual conditions of occupational health activities in small-scale enterprises in Japan: system for occupational health, health management and demands by small-scale enterprises. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi. 1999; 41: 190–201. (Article in Japanese)

Okubo T. The present state of occupational health in Japan. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1997; 70: 148–152.

Leyland AH, Goldstein H. Multilevel Modelling of Health Statistics. West Sussex: Wiley; 2001.

Siahpush M, Singh GK. Sociodemographic predictors of pap test receipt, currency and knowledge among Australian women. Prev Med. 2002; 35: 362–368.

Chamot E, Perneger TV. Men’s and women’s knowledge and perceptions of breast cancer and mammography screening. Prev Med. 1999; 34: 380–385.

Nijis HGT, Essink-Bot ML, DeKoning HJ, Kirkels WJ, Schroder FH. Why do men refuse or attend population-based screening for prostate cancer? J Public Health Med. 2000; 22: 312–316.

Tanaka T, Tsushima S, Morio S, Okamoto N, Sato T, Kakigawa Y, et al. Analysis of cancer screening participation in regional inhabitants. Kosei no Shihyo. 1990; 37: 21–28. (Article in Japanese)

Morio S, Okamoto N, Tanaka T, Tsushima S, Sato T, Takigawa Y, et al. Participation of regional inhabitants in cancer screening. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 1990; 37: 559–568. (Article in Japanese)

Hirano Y, Ojima T. Analysis of factors influencing participation in the cervical cancer screening programme in the community in Japan. J Epidemiol. 1997; 7: 125–133.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey on Demands of Health and Welfare Services. Tokyo: Health and Welfare Statistics Association; 2000. (Article in Japanese)

Sackett DL. Bias in analytic research. J Chronic Dis. 1979. 32: 51–63.

Delgado-Rodriguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004; 58: 635–641.

Tsubono Y, Fukao A, Hisamichi S, Hosokawa T, Sugawara N. Accuracy of self-report for stomach cancer screening. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994; 47: 977–981.

Caplan LS, Mandelson MT, Anderson LA. Health Maintenance Organization: Validity of self-reported mammography: examining recall and covariates among older women in a Health Maintenance Organization. Am J Epidemiol. 2003; 57: 267–272.

Armstrong K, Long JA, Shea JA. Measuring adherence to mammography screening recommendations among low-income women. Prev Med. 2004; 38: 754–760.

Watanabe Y, Morita M. Screening for gastric and colorectal cancer in Japan. Journal of Kyoko Prefectural University of Medicine. 2003; 112: 371–378. (Article in Japanese)

Ozasa K. Lung cancer screening, today. Journal of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine. 2003; 112: 395–402. (Article in Japanese)

Nakaya N, Ohmori K, Suzuki Y, Hozawa A, Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y, et al. A survey regarding the implementation of cancer screening among municipalities in Japan. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2004; 51: 530–539. (Article in Japanese)

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60: 7–12.

Kunst A, Mackenbach J. Measuring socioeconomic inequalities in health. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 1997.

Ohtake F. Inequalities in Japan. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Shinbunsha; 2005. (Article in Japanese)

Diez-Roux AV. Multilevel analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000; 21: 171–192.

Subramanian SV, Jone K, Duncan C. Multilevel Methods for Public Health Research. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF editors. Neighborhoods and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. p. 65–111.

Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Increased excess deaths in urban areas: quantification of geographical variation in mortality in Japan, 1973 to 1998. Health Policy. 2004; 68: 233–244.

Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Cause-specific mortality differences across socioeconomic position of municipalities in Japan, 1973–77 and 1993–98: increased importance of injury and suicide in inequality for ages under 75. Int J Epidemiol. 2005; 34: 100–109.

Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Accumulation of health risk behaviors is associated with lower socioeconomic status and women’s urban residence: a multilevel analysis in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2005; 5: 53.

Christenfeld N, Glynn LM, Phillips DP, Shrira I. Exposure to New York City as a risk factor for heart attack mortality. Psychosom Med. 1999; 61: 740–743.

Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Latha E, Monaharan M, Vijay VI. Impacts of urbanization on the lifestyle and on the prevalence of diabetes in native Asian Indian population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999; 44: S207-S213.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuda, Y., Nakamura, K., Takano, T. et al. Socioeconomic status and cancer screening in Japanese males: Large inequlaity in middle-aged and urban residents. Environ Health Prev Med 12, 90–96 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02898155

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02898155