Abstract

Purpose

Low income is an established risk factor for suicidal thoughts and attempts. This study aims to explore income within a social rank perspective, proposing that the relationship between income and suicidality is accounted for by the rank of that income within comparison groups.

Methods

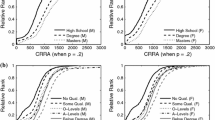

Participants (N = 5779) took part in the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey across England. An income rank variable was created by ranking each individual’s income within four comparison groups (sex by education, education by region, sex by region, and sex by education by region). Along with absolute income and demographic covariates, these variables were tested for associations with suicidal thoughts and attempts, both across the lifetime and in the past year.

Results

Absolute income was associated with suicidal thoughts and attempts, both across the lifetime and in the past year. However, when income rank within the four comparison groups was regressed on lifetime suicidal thoughts and attempts, only income rank remained significant and therefore accounted for this relationship. A similar result was found for suicidal thoughts within the past year although the pattern was less clear for suicide attempts in the past year.

Conclusions

Social position, rather than absolute income, may be more important in understanding suicidal thoughts and attempts. This suggests that it may be psychosocial rather than material factors that explain the relationship between income and suicidal outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization (2014). http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/en/

Office of National Statistics (2014). http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/taxonomy/index.html?nscl=Suicides+and+Intentional+Self-harm

Baumeister RF (1990) Suicide as escape from self. Psychol Rev 97:90–113

O’Connor RC (2011) Towards an Integrated Motivational-Volitional of Suicidal Behaviour. In: O’Connor RC, Platt S, Gordon J (eds) International handbook of suicide prevention: research, policy and practice. Wiley Blackwell, New York, pp 181–198

O’Connor RC, Nock MK (2014) The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry 1:73–85

Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, House JS (2000) Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. Br Med J 320:1200–1204

Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE (2006) Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence. Soc Sci Med 62:1768–1784

Sher L (2006) Per capita income is related to suicide rates in men but not in women. J Men’s Health Sex 3(1):39–42

Ferrada-Noli M (1997) Social psychological variables in populations contrasted by income and suicide rate: Durkheim revisited. Psychol Rep 81(1):307–316

McMillan KA, Enns MW, Asmundson GG, Sareen J (2010) The association between income and distress, mental disorders, and suicidal ideation and attempts: findings from the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology surveys. J Clin Psychiatry 71(9):1168–1175

Chung C, Pai L, Kao S, Lee M, Yang T, Chien W (2013) The interaction effect between low income and severe illness on the risk of death by suicide after self-harm. Crisis 34(6):398–405

Kondo N, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Takeda Y, Yamagata Z (2008) Do social comparisons explain the association between income inequality and health?: relative deprivation and perceived health among male and female Japanese individuals. Soc Sci Med 67:982–987

Eibner C, Sturm R, Gresenz CR (2004) Does relative deprivation predict the need for mental health services. J Mental Health Policy Econ 7:167–175

Marmot M, Wilkinson RG et al (2001) Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. Br Med J 322:1233–1236

Festinger L (1954) A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat 7(2):117–140

Price JS (1972) Genetic and phylogenetic aspects of mood variations. Int J Mental Health 1:124–144

Sloman L (2000) How the involuntary defeat strategy relates to depression. In: Sloman L, Gilbert P (eds) Subordination and defeat: an evolutionary approach to mood disorders and their therapy. Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 47–67

Gilbert P, Allan S (1998) The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: an exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol Med 28:585–598

Gilbert P, Allan S, Brough S, Melley S, Miles J (2002) Relationship of anhedonia and anxiety to social rank, defeat and entrapment. J Affect Disord 71(1–3):141–151

Von Holst D (1986) Vegetative and somatic components of tree shrews’ behaviour. J Auton Nervous Syst (Suppl.):657–670

Shively CA, Laber-Laird K, Anton RF (1997) Behavior and physiology of social stress and depression in female cynomolgus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry 41:871–882

Taylor PJ, Gooding P, Wood AM, Tarrier N (2011) The role of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety, and suicide. Psychol Bull 137:391–420

Dixon AK, Fisch HU, Huber C, Walser A (1989) Ethological studies in animals and man: their use of psychiatry. Pharmacopsychiatry 22:44–50

Williams JMG (1997) Cry of pain: understanding suicide and selfharm. Penguin, Harmondsworth

O’Connor RC (2003) Suicidal behavior as a cry of pain: test of a psychological model. Arch Suicide Res 7:297–308

Rasmussen S, Fraser L, Gotz M, MacHale S, Mackie R, Masterton G, McConachie S, O’Connor RC (2010) Elaborating the cry of pain model of suicidality: testing a psychological model in a sample of first-time and repeat self-harm patients. Br J Clin Psychol 49:15–30

O’Connor RC, Smyth R, Ferguson E, Ryan C, Williams JMG (2013) Psychological processes and repeat suicidal behavior: a four year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 81:1137–1143

Taylor PJ, Wood AM, Gooding P, Tarrier N (2011) Prospective predictors of suicidality: defeat and entrapment lead to changes in suicidal ideation over time. Suicide Life Threat Behav 41:297–306

Brown GDA, Gardner J, Oswald AJ, Qian J (2008) Does wage rank affect employees’ well-being? Ind Relat 47:355–389

Boyce CJ, Brown GDA, Moore S (2010) Money and happiness: rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychol Sci 21:471–475

Wood AM, Boyce CJ, Moore SC, Brown GD (2012) An evolutionary based social rank explanation of why low income predicts mental distress: a 17 year cohort study of 30,000 people. J Affect Disord 136(3):882–888

Daly M, Boyce C, Wood A (2015) A social rank explanation of how money influences health. Health Psychol 34:222–230

McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R (2009) Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: results of a household survey. National Centre for Social Research, London

Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G (1992) Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med 22:465–486

McClements LD (1977) Equivalence scales for children. J Public Econ 8:191–210

Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC (1958) Social class and mental illness: a community study. Wiley, New York

Brown GW, Harris T (1978) Social origins of depression. Free Press, New York

Dohrenwend B, Levav I, Shrout P, Schwartz S, Naveh G, Link B, Stueve A (1992) Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science (New York, N.Y.) 255(5047):946–952

Gilbert P, McEwan K, Irons C, Bhundia R, Christie R, Broomhead C, Rockliff H (2010) Self-harm in a mixed clinical population: the roles of self-criticism, shame, and social rank. Br J Clin Psychol 49(Pt 4):563–576

Gilbert P, Broomhead C, Irons C, McEwan K, Bellew R, Mills A, Gale C, Knibb R (2007) Development of a striving to avoid inferiority scale. Br J Soc Psychol 46:633–648

Williams K, Gilbert P, McEwan K (2009) Striving and competing and its relationship to self-harm in young adults. Int J Cogn Ther 2(3):282–291

O’Connor RC (2007) The relations between perfectionism and suicidality: a systematic review. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 37(6):698–714

Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GG (2011) Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68(4):419–426

Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Williams D (2008) Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry 192:98–105

Acknowledgments

The data was accessed through the UK Data Archive and can be downloaded from http://www.data-archive.ac.uk. The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity survey (APMS) is archived as SN 6379. This research was supported in part by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grant ES/K00588X/1.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

All studies have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wetherall, K., Daly, M., Robb, K.A. et al. Explaining the income and suicidality relationship: income rank is more strongly associated with suicidal thoughts and attempts than income. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50, 929–937 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1050-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1050-1