Abstract

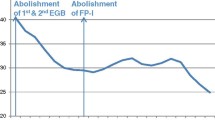

We analyse the decision to drop out of post-compulsory education over the period 1985–1994 using data from the Youth Cohort Surveys. We show that the dropout rate declined between 1985 and 1994, in spite of the rising participation rate in education, but is still substantial. Dropping out is more or less constant over the period of study, though the risk of dropout does vary with young people’s prior attainment, ethnicity, family background and the state of the labour market. The course of study has a substantial effect on the risk of dropout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our data refer to England and Wales where young people complete their compulsory schooling at the age of 16, and may then proceed to a period of continued education, typically up to the age of 18, before entrance to the labour market or to university. The period of education between 16 and 18 is voluntary and is referred to throughout this paper as post-compulsory education.

The Local Authority District is regarded in this study as a self-contained labour market because young people tend to be less geographically mobile than adults and they are therefore likely to respond to ‘local’ labour market conditions.

In 1984, the staying on rate was comparatively low with only 41% of all 16 year olds entering post-compulsory education, whereas by 1994 this figure had risen to 71%.

A potential limitation of the method we adopt is that the effects of unobservables are assumed to be uncorrelated with the observed covariates.

As an aside, it is worth noting that the previous literature has typically estimated cross-sectional binary choice models of the decision to drop out, conditional on having stayed on. The few longitudinal models of dropout in higher education do not take into consideration the initial decision made by the individual to enter university.

In 1997, 11 states required the youth to attend school until age 18 (National Center for Education Statistics 1998).

YCS2–YCS6 are the only versions where sample members complete an annual survey. In YCS7–YCS9, respondents complete a retrospective diary covering a 2 year period (i.e. for the period of 16–18), which may exacerbate the problem of recall bias. Since this is the period in which young people pursue post-compulsory education, we decided not to use the more recent data. In addition, YCS10–YCS11 had only one sweep at the time of going to press, which means that it is not useful for our purposes.

Specifically, young people are sent a postal questionnaire, which they are asked to complete and return.

There is some concern about the quality of the retrospective diary information contained in the YCS, which may lead to measurement error in the dependent variable. To reduce the likelihood of measurement error we carefully examined the diary information and made the following assumptions. First, if a young person in post-compulsory education indicated that they had a spell of employment, for instance, between two spells of education, then the spell of employment was recoded to education. This occurred most frequently in the Christmas and Easter holiday period, which implies that the employment spell referred to a casual job. Since the young person returned to education, it is safe to assume that their main activity is still as a student. Second, the imposition of two conditions for a young person to be a dropout (see the text above) also reduces measurement error because young people whose diaries are inaccurate but nevertheless sit for the examination are counted as graduates. Of course, we cannot completely rule out the presence of measurement error in our data, however, this is unlikely to be any worse than the measurement error associated with many other longitudinal datasets, such as the BHPS and the NCDS, which are routinely used by researchers to estimate models similar to those estimated in this paper.

‘High’ academic education refers to young people taking A levels, the traditional route to higher education, whereas ‘low’ refers to young people repeating their GCSE exams (see footnote 8). Similarly, a ‘high’ vocational education, for instance, refers to BTEC National Diplomas in Business Studies, Science, Engineering, which are ‘equivalent’ to A levels, and ‘low’ vocational education includes basic business, typing and similar courses.

For the single risk model, r i = 1 and r i = 2 are combined but the econometric methods are identical to the competing risks model discussed in the text.

In the econometric analysis, since a young person cannot by definition be observed to start and quit post-compulsory education in the same month, we combine the months October and November thereby giving a total of 20 time periods.

The baseline hazard is estimated non-parametrically, which means that the hazard can vary freely over time but is assumed to be constant within each time interval. This is equivalent to assuming an exponential survival in each time interval.

The marginal effects are actually computed at \(\gamma = 12\) for females and \(\gamma = 10\) for males.

Students sit for the General Certificate of Secondary Examination (GCSE) at the end of their compulsory schooling, typically at age 16, in up to ten subjects dictated by the National Curriculum. The grades that could be achieved at the time of this study were A (high) through to G (low).

We also estimated a model with interaction effects between academic attainment and the local unemployment rate to see if their response to labour market conditions differed. For males, there was no statistically significant effect and for females, the model would not converge because of the small number of observations in some categories.

This version of the paper is available at the following web address: http://www.lancs.ac.uk/staff/ecasb/work.html.

References

Andrews M, Bradley S, Stott D (2002) Matching the demand for and the supply of training in the school-to-work transition. Econ J 112(478):C201–C219

Arulampalam W, Naylor R, Smith JP (2004) Factors affecting the probability of first-year medical student dropout in the UK: a logistic analysis for the entry cohorts of 1980–92. Medical Education 38(5):492–503

Arulampalam W, Naylor R, Smith JP (2005) Effects of in-class variation and student rank on the probability of withdrawal: cross-section and time-series analysis for UK university students. Econ Educ Rev 24(3):251–262

Armor J (1992) Why is black educational achievement rising? Public Interest 108:65–80 (Summer)

Ashenfelter O, Rouse C (1998) Income, schooling and ability: evidence from a new sample of identical twins. Q J Econ 113(1):253–284

Audit Commission (1993) Unfinished business: full time educational courses for 16–19 year olds. HMSO, London

Becker GS (1964) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. Columbia University Press, New York

Becker GS, Lewis HG (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 81(2):s279–s288

Becker GS, Tomes N (1976) Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 84(4):s143–s162

Behrman JR, Taubman P (1986) Birth order, schooling and earnings. J Labor Econ 4(3):s121–s145

Bishop JH, Mane F (2001) The impacts of minimum competency exam graduation requirements on high school graduation, college attendance and early labour market success. Labour Econ 8(2):203–222

Booth AL, Satchell SE (1995) The hazards of doing a Ph.D.: An analysis of completion and withdrawal rates of British Ph.D. students in the 1980s. J R Stat Soc Ser A 158(2):297–318

Bradley S, Taylor J (2004) Ethnicity, educational attainment and the transition from school. Manch Sch 72(3):317–346

Card D, Lemieux T (2000) Dropout and enrollment trends in the post-war period: what went wrong in the 1970s? In: Gruber J (ed) An economic analysis of risky behaviour among youth. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Carpenter P, Hayden M (1987) Girls academic achievements: single sex versus co-educational schools in Australia. Sociol Educ 60(3):156–167

Chuang HL (1994) An empirical study of re-enrolment behaviour for male high-school dropouts. Appl Econ 26(11):1071–1081

Chuang HL (1997) High school youths’ dropout and re-enrolment behaviour. Econ Educ Rev 16(2):171–186

Cohany S (1986) What happened to the high school class of 1985? Mon Labor Rev 109(4):28–30

Davies R, Elias P (2003) Dropping out: a study of early leavers from higher education. Research Report 386, London, DfES

Eckstein Z, Wolpin KI (1999) Why youths drop out of high school: the impact of preferences, opportunities, and abilities. Econometrica 67(6):1295–1339

Evans W, Schwab R (1995) Finishing high school and starting college: do Catholic schools make a difference? Q J Econ 110(4):941–974

Finn CE, Toby J (1989) Dropouts and grownups. Public Interest 96:131–136 (Summer)

Hanushek EA (1992) The trade-off between child quantity and quality. J Polit Econ 100(1):84–117

Heckman J, Singer B (1984) A method for minimising the impact of distributional assumptions in econometric models of duration. Econometrica 52(2):271–320

Hodkinson P, Bloomer M (2001) Dropping out of further education: complex causes and simplistic policy solutions. Res Pap Educ 16:117–140

Jakobsen V, Rosholm M (2003) Dropping out of school? A competing risks analysis of young immigrants’ progress in the education system. IZA Discussion Paper No. 918, IZA, Bonn

Johnes G, McNabb R (2004) Never give up on the good times: student attrition in the UK. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 66(1):23–48

Johnes J, Taylor J (1991) Non-completion of a degree course and its effect on the subsequent experience of non-completers in the labour market. Stud High Educ 16(1):73–81

Keep E, Mayhew K (1999) The assessment: knowledge, skills and competitiveness. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 15(1):1–15

Koshal RK, Koshal M, Marino B (1995) High school dropouts: a case of negatively sloping supply and positively sloping demand curves. Appl Econ 27(8):751–757

Lancaster T (1990) The econometric analysis of transition data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Light A, Strayer W (2000) Determinants of college completion. J Hum Resour 35(2):299–332

Manski C, Sandefur G, Lanahan S, Powers D (1992) Alternative estimates of the effects of family structure during adolescence on high school graduation. J Am Stat Assoc 87(417):25–37

Markey JP (1988) The labor market problems of today’s high school dropouts. Mon Labor Rev 111(6):36–43

McElroy SW (1996) Early childbearing, high school completion and college enrollment: evidence from 1980 high school sophomores. Econ Educ Rev 15(3):303–324

Meyer BD (1990) Unemployment insurance and unemployment spells. Econometrica 58(4):757–782

National Center for Education Statistics (1998) Digest of education statistics 1997. Washington DC, US Department of Education

Neal D (1997) The effects of Catholic secondary schooling on educational achievement. J Labor Econ 15(1):98–123

Nguyen A, Taylor J, Bradley S (2002) High school dropouts: a longitudinal analysis. Department of Economics, Lancaster University mimeo, Lancaster

Nguyen A, Taylor J, Bradley S (2006) The effect of Catholic schooling on educational and labour market outcomes: further evidence from NELS. Bull Econ Res (in press)

Payne J (2001) Patterns of participation in full-time education after 16: an analysis of the England and Wales. Youth Cohort Studies, Department for Education and Skills, Research Report No. 307

Prais SJ (1995) Productivity, education and training: an international perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Prentice R, Gloeckler L (1978) Regression analysis of grouped survival data with application to breast cancer data. Biometrics 34(1):57–67

Sander W, Krautmann AC (1995) Catholic schools, dropout rates and educational attainment. Econ Inq 33(2):217–233

Spence M (1974) Market signaling. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Stewart M (1996) Heterogeneity specification in unemployment duration models. Department of Economics, University of Warwick

Toby J (1989) Of dropouts and stay-ins: the Gershwin approach. Public Interest 95:3–13 (Spring)

Toby J, Armor DJ (1992) Carrots or sticks for high school dropouts? Public Interest 106:76–90 (Winter)

Vandenberghe V (2000) Leaving teaching in the French-speaking community of Belgium: a duration analysis. Educ Econ 8(3):221–240

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous referees and the editor of the journal for the helpful comments, which have greatly improved our paper. The authors are also grateful to the Social and Community Planning Research for providing the Youth Cohort Surveys and for the information that enabled us to combine several data sets. We are grateful to Anna Vignoles and the participants at the Human Resource Economics Study Group (Lancaster) for the helpful comments, particularly to Rob Crouchley, Geraint Johnes, Anh Nguyen, Dave Stott and Jim Taylor. The authors accept responsibility for the remaining errors and omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Christian Dustmann

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bradley, S., Lenton, P. Dropping out of post-compulsory education in the UK: an analysis of determinants and outcomes. J Popul Econ 20, 299–328 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-006-0110-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-006-0110-y