Abstract

Purposes

We evaluated the prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy and investigated the role of polypharmacy as a predictor of length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality.

Methods

Thirty-eight internal medicine wards in Italy participated in the Registro Politerapie SIMI (REPOSI) study during 2008. One thousand three hundred and thirty-two in-patients aged ≥65 years were enrolled. Polypharmacy was defined as the concomitant use of five or more medications. Linear regression analyses were used to evaluate predictors of length of hospital stay and logistic regression models for predictors of in-hospital mortality. Age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, polypharmacy, and number of in-hospital clinical adverse events (AEs) were used as possible confounders.

Results

The prevalence of polypharmacy was 51.9% at hospital admission and 67.0% at discharge. Age, number of drugs at admission, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were independently associated with polypharmacy at discharge. In multivariate analysis, the occurrence of at least one AE while in hospital was the only predictor of prolonged hospitalization (each new AE prolonged hospital stay by 3.57 days, p < 0.0001). Age [odds ratio (OR) 1.04; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–1.08; p = 0.02), comorbidities (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.12–1.24; p < 0.0001), and AEs (OR 6.80; 95% CI 3.58–12.9; p < 0.0001) were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality.

Conclusions

Although most elderly in-patients receive polypharmacy, in this study, it was not associated with any hospital outcome. However, AEs were strongly correlated with a longer hospital stay and higher mortality risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polypharmacy is a problem for rational drug prescribing in elderly patients [1–4], the largest consumers of medicines often taking from two to five drugs on a regular basis. A survey of community-dwelling elderly showed that >90% of people ≥65 years used at least one drug weekly and more than 40% took five or more [5]. Among hospitalized elderly, the prevalence of polypharmacy ranged from 20% to 60%, reflecting different criteria used to select patients and collect medication data [6–8]. Although polypharmacy has no generally accepted definition, most often it is defined by cutoffs in terms of the number of medications taken ranging from two to ten [9–12]. However, regardless of the definition, its prevalence has been reported to increase with age and is associated with an increased risk of inappropriate drug prescription, underuse of effective treatment, medication errors, poor adherence to pharmacological therapies, drug/drug and drug/disease interactions, and adverse effects [3, 13–18]. The incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) increases exponentially rather than linearly with the number of drugs taken, and advanced age and polypharmacy are associated with a substantial increase in ADR risk [4, 10, 15, 19–21].

Polypharmacy is often a consequence of multiple chronic conditions, which lead physicians to prescribe more than one drug, thus increasing the risk of disability, hospitalization, and mortality [22–27]. Although the available guidelines have improved and rationalized drug prescription in many disease-oriented fields, they are still weak for elderly people exposed to polypharmacy due to multiple chronic conditions [28, 29]. One chronic condition can potentially worsen another, and drugs can interact negatively with others, increasing the risk of ADRs and reducing the expected benefit. Older patients and patients with multiple chronic disorders are almost always excluded from trials to verify drug effectiveness because of the fear they may be unable to complete the studies due to poor compliance, frequent side effects, or death. Subsequently, many drugs are prescribed to these patients even though the drug benefit–risk profile is not known [27, 28]. Many risk factors for polypharmacy have been identified, including demographic aspects such as age, race, education, sex, health, number of chronic diseases, living arrangements, and number and characteristics of healthcare providers [1, 2, 14–16]. Elderly patients with multiple chronic conditions are common in general medicine specialties such as internal and geriatric medicine. These patients are usually frail, are highly sensitive to pharmacotherapy due to changes in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters, and are often admitted with acute diseases, which may increase their susceptibility to polypharmacy [10, 21].

Hospitalization is a major risk for older persons, particularly the very old. In many cases, hospitalization is associated with an irreversible decline in functional status, cognitive performance, and quality of life [14, 20, 24, 30]. Although polypharmacy and the risk of inappropriate use of medications in community-living and institutionalized elderly patients have been amply described, few studies have analyzed the prevalence, predictors, and in-hospital outcomes of polypharmacy in the elderly. The aims of this study were to evaluate in a sample of hospitalized elderly people the prevalence of polypharmacy (defined as five or more drugs) at admission and at discharge from internal and geriatric medicine wards, to assess the prevalence of the most frequently prescribed medications, to analyze the predictors of polypharmacy at hospital discharge, and to investigate the role of polypharmacy as a predictor of longer hospital stay and increased in-hospital mortality.

Patients and methods

Methods

This prospective cohort study ran from January 2008 to December 2008 in 38 hospitals in different Italian regions, all of which participated in the Registro Politerapie SIMI (REPOSI) study, a collaborative effort between the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI) and the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research. The REPOSI study was designed with the purpose of setting up a network of internal medicine wards to investigate the prevalence and correlates of polymorbidity and polypharmacy in hospitalized elderly patients. Participation was voluntary, but we were careful to ensure participating centers were representative in terms of countrywide distribution and size and had unselected admissions from their own territory or the emergency room. The REPOSI study was specifically designed to describe the prevalence of multiple concurrent diseases and treatments in hospitalized elderly patients, to correlate the patient’s clinical characteristics with the type and number of diseases and treatments, and to evaluate the main clinical outcomes at discharge.

Study population

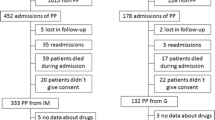

Patients were eligible for REPOSI if: (1) they were admitted to one of the 38 participating internal medicine wards during the 4 index weeks chosen for recruitment (one in February, one in June, one in September, and one in December 2008); (2) their age was ≥65 years; 3) they gave informed consent. Each ward had to enrol at least the first ten consecutive eligible patients during each index week. During each index week, all wards had to complete the register of all patients admitted to the ward and indicate those who were consecutively enrolled in the study. For patients who were excluded, the reason had to be given. On the basis of these data, during the 4 weeks, the recruitment rate for each ward was nearly 40% of patients admitted. Sixty-eight percent of them were excluded because of age <65 years. Other reasons for exclusion were refusal to participate or to sign informed consent (23%), seriousness of patient’s clinical condition or admission in terminal state (6%), and other reasons (3%). No difference for age or sex (the only available data) emerged for these patients in comparison with the enrolled sample. Of 1,411 patients enrolled, 79 (5.6%) were excluded because of missing or incomplete data (25 had missing data on hospital outcome and 54 on most sociodemographic and clinical characteristics due to errors or omissions in data input and recording), and 1,332 fulfilled the requirements for the analysis. The 54 patients excluded because of missing data showed no significant differences in outcomes in comparison with the analyzed cohort.

Data collection

All data obtained from the patient’s medical records were entered into a standardized Web-based “essential” Case Report Form (CRF) by the attending physicians. The following data were recorded for each patient: basic sociodemographic details, clinical parameters, diagnoses and treatments at hospital admission and discharge, clinical events in hospital, and outcome. Before starting the enrolment, all investigators received instructions on how to standardize the procedure for patient inclusion and how to enter and code data in the electronic CRF. All data were collected and checked by a central monitor institution (Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Milan) in full compliance with Italian law on personal data protection. Under the applicable legal principles on patient registries, the study did not require the approval of an ethical committee.

Diagnoses and comorbidities

At admission, the main reason for that admission and any comorbidities were recorded. At discharge, all diagnoses listed in the medical record were listed, confirmed by clinical examination, anamnesis, laboratory, and instrumental data collected by the attending physicians, and encoded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), Sixth Edition (World Health Organization, 1987) [31]. Chronic diseases identified by Veehof et al. [12] analyzed as potential predictors of polypharmacy were hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or bronchial asthma, osteoporosis or osteoarthritis, gastrointestinal disease (peptic or duodenal ulcer, nonspecific bowel inflammation), and psychiatric disorders (dementia, depression). Depression was eventually excluded because it was present in only four patients. Comorbidity was evaluated by the Charlson comorbidity index [32], a method used in longitudinal studies for classifying comorbid conditions that might affect the risk of mortality. This weighted index takes into account the number and seriousness of comorbid diseases. Specific diseases are graded in three levels of severity: low (≤2), moderate (3–4), and severe (≥5) according to the level of individual organ function and prognostic importance.

Drugs and polypharmacy

All drugs being taken at hospital admission and all medications recommended at discharge were recorded and encoded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system (ATC) (WHO 1990) [33]. Drug classes were determined in relation to the ATC third-level (pharmacological subgroup) classification. The numbers of drugs taken at admission and discharge were compared for each patient. Although there is still no consensus or commonly used cutoff for polypharmacy, as previous studies have mostly used four or five drugs as cutoff points, and most drugs prescribed to elderly patients are for chronic therapies, we defined polypharmacy as exposure of a patient to five or more different medications [2–4, 9]. The prevalence of polypharmacy was analyzed in 5-year age brackets: 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, ≥ 90 years. Polypharmacy was evaluated at hospital admission (all 1,332 patients) and at discharge (the 1,155 sent home). Data on drug prescription were not available for 111 patients who were not discharged to go home and for 66 who died in hospital. However, no statistically significant difference was observed at admission between the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 111, 66, and 1,155 patients.

Predictors, clinical events, and adverse outcome

Patients’ characteristics, diagnoses, comorbidity, and AEs were considered potential predictors of polypharmacy. AEs were defined as any change in the individual’s health—with specific symptoms and signs of recent onset—occurring after hospital admission [34, 35]. Length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality were used as outcome measures when evaluating the effect of polypharmacy. Of the 111 patients who were not discharged to go home and were subsequently excluded from the analysis, 61 were transferred to other hospital wards because of acute medical or surgical disease during hospitalization, 44 were transferred to rehabilitation units or long-term-care facilities, and six were terminally ill at admission and thus transferred to end-of-life-care units.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentages and continuous variables as means [± standard deviation (SD)]. The differences in distribution of categorical variables between patients with and without polypharmacy were computed using the chi-squared test, whereas the t-test was used for continuous variables. Determinants of polypharmacy treatment at discharge were studied in 551 patients without polypharmacy at admission. We applied logistic regression models to identify patient-related characteristics associated with polypharmacy. Each model was adjusted for sex, age, number of drugs at admission, and occurrence of at least an AE in hospital. Diagnoses were separately tested (hypertension, ischemic heart diseases, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, COPD, dementia, cerebrovascular diseases, liver diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, osteoporosis/osteoarthritis, chronic renal failure, anemia, and malignancy). For each variable, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Outcome measures (predictors of length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality) were analyzed using linear and logistic regression analysis, respectively. Regression coefficients, OR and their 95% CI were calculated at univariate analysis and after adjustment for sex, age, comorbidities at admission, number of drugs at admission, and occurrence of at least one AE in hospital. In all multivariate models, standard errors (SE) were corrected to allow for the nonindependence of patients within the same ward. All statistical calculations were done with the software JMP v 8.0.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and STATA v11.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Of the 1,332 patients enrolled, 772 (54.2%) were women, the average age was 79.4 years (SD ± 7.5), and 616 (46%) were ≥80 years or more. At admission, almost 90% of patients came from home, where 42% lived with their spouse, 24% alone, 19% with children, and the remainder from nursing home. The mean number of diagnoses was 5.2 (SD ± 2.3). The Charlson comorbidity index mean score was 0.5 (SD ± 0.8), and 545 (40%) patients had a Charlson index rated as moderate or severe. The most frequent diagnoses at hospital admission were hypertension (57.8%), diabetes mellitus (24.0%), coronary heart disease (CHD, 23.0%), atrial fibrillation (AF, 20.6%), COPD (20.0%), and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (19.5%).

Prevalence of polypharmacy

At admission, patients had an average of 5.2 (SD ± 2.3) diagnoses, were in treatment with an average of 4.9 (SD ± 2.9) drugs, and 51.9% were taking five or more different drugs (polypharmacy). Figure 1 shows the prevalence of polypharmacy at admission in relation to age. The prevalence rate was highest at ages 70-74 and 80-84 years, with nearly 60% of patients in polypharmacy. At discharge, the prevalence of patients in polypharmacy increased from 51.9% to 67.0% (+15.1%); patients were discharged with an average of 6.0 (SD ± 2.9) drugs per person and an average of 5.9 (SD + 2.5) diagnoses.

Among the 1,155 patients discharged, 341 (29.5%) had no polypharmacy at either admission or discharge, 210 (18.2%) shifted to polypharmacy at discharge, 40 (3.5%) were on polypharmacy at admission but not at discharge, and 564 (48.8%) were on polypharmacy at both admission and discharge. Figure 2 compares patient distribution in relation to the number of drugs at admission and at discharge and shows a clear increase in the number of patients receiving five or more different medications at discharge.

Table 1 lists the ten most frequently prescribed drug classes at admission and discharge. Except for blood-glucose-lowering drugs (A10B), the prevalence of treated patients was higher at discharge.

Predictors of polypharmacy

Table 2 shows the results of univariate analysis of polypharmacy predictors in relation to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the 1,332 patients at admission and the 1,155 discharged. In both samples, age ≥85 years, education, number of diagnoses, comorbidity, number of drugs, number of AEs during hospital stay, diagnosis of hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, COPD, chronic renal failure, and osteoporosis/osteoarthritis were associated with the use of polypharmacy. At admission, a diagnosis of gastrointestinal disorders was also positively related to polypharmacy.

Table 3 shows analyses of the 551 patients without polypharmacy at admission, comparing sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 341 who received fewer than five drugs at discharge and the 210 discharged with polypharmacy. Upon univariate analysis, the number of diagnoses, having at least one AE, length of hospital stay, and diagnosis of hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, COPD, osteoporosis/osteoarthritis, or chronic renal failure were predictors of polypharmacy at discharge.

At multivariate analysis in the full sample of 1,155 patients for whom prescription data were available both at admission and discharge, age, number of drugs at admission, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and COPD were the most important predictors of polypharmacy (Table 4).

In a post hoc analysis of the same 1,155 patients, the predictors of changes in the numbers of drug from admission to discharge were evaluated. For 148 patients (13.0%), the number of drugs at discharge were fewer than at admission (delta <0), whereas for 295 (25.4%), there was no difference (delta = 0) and for 712 (61.6%) there was an increase (delta >0). Each disease was separately tested in multivariate analyses to assess whether it was responsible for the change in the number of drugs at discharge. Hypertension increased the number of drugs at discharge by a mean of 0.33 (95% CI 0.09–0.56; p = 0.008) independently of sex, age, number of drugs at admission, ward, and occurrence of at least one AE in hospital. Likewise, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and COPD increased the number of drugs at discharge by a mean of 0.28 (95% CI 0.04–0.53; p = 0.02), 0.61 (95% CI 0.22–1.00; p = 0.003), and 0.61 (95% CI 0.28–0.95; p = 0.001). Dementia reduced the number of drugs at discharge by a mean of 0.76 (95% CI 0.30–1.22; p = 0.0002).

Length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality

In the entire sample of 1,332 elderly patients, 1,155 (86.7%) were discharged to go home, 111 (8.3%) were transferred to another ward, and 66 (5.0%) died in hospital. The average hospital stays were, respectively, 13.1 (SD ± 11.6), 13.1 (SD ± 11.3), and 10.7 (SD ± 8.0) days. Table 5 shows the outcomes at discharge in relation to polypharmacy at admission and the univariate and multivariate analyses of predictors of length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality. Both analyses found that at least one AE while in hospital was positively related to the time in hospital, prolonging it by 3.57 days (95% CI 2.32–4.83; p < 0.0001).

Predictors of in-hospital mortality were age (OR = 1.04; 95% CI 1.01–1.09; p = 0.02), and comorbidity (OR = 1.18; 95% CI 1.12–1.24; p < 0.0001). An AE during hospital stay increased the risk of in-hospital mortality by nearly sevenfold, independently of sex, age, comorbidity, or polypharmacy (OR = 6.80; 95% CI 3.58–12.9; p < 0.0001). Polypharmacy was not a predictor for either length of hospital stay or in-hospital mortality. Adding the ward to the covariates of logistic regression analysis had no effect on the results.

Sensitivity analysis

As the chosen cutoff of five or more drugs to define polypharmacy is not unanimously accepted, and to estimate the sensitivity of the results to this cutoff, we re-ran the multivariate analysis for four and six or more drugs. Estimates for predictors of length of hospital stay and mortality were almost identical to those reported in Table 5, with statistical significance confirmed for the same variables. Among different diseases, whereas hypertension and heart failure were still statistically significant, others were not always present, probably because of random fluctuations or complex interactions between the single variables in the full model.

Discussion

This study shows how common polypharmacy is in elderly patients admitted to an internal medicine or geriatric ward. More than 50% of patients aged ≥65 in a network of 38 Italian internal medicine hospital wards and who voluntarily participated in the REPOSI study were taking five or more different drugs (polypharmacy), mostly as chronic therapies. Polypharmacy was more common in people between 70 and 84 years of age and was related to comorbidities. The decline in polypharmacy in people >85 years of age might be due to poor drug tolerance with age or with doctors’ fears of serious side effects being more common in very elderly patients, as a reduced morbidity with age is unlikely. Hospitalization did not lead to a reduction in the number of drugs. Only 13% of patients had fewer drugs prescribed at discharge than at admission, and >60% had an increase. Moreover, among patients admitted with polypharmacy, only 3.5% were discharged with fewer than five different medicines. This finding suggests that most disorders affecting elderly people admitted to hospital are chronic and need stable therapy. The increase in the number of prescriptions at discharge suggests that hospitalization leads to new diagnoses that require further drugs or that old therapies need to be replaced by new, more complex, therapies. The increases involved all classes of drugs, thus excluding the possibility that the additional drugs were needed because of inadequate treatment at home.

Prevalence of polypharmacy

Few studies have analyzed the prevalence of polypharmacy in a general hospital setting. They used different thresholds for polypharmacy, and prevalence at admission ranged from 20% to 60% [6, 7] and was higher at hospital discharge. In the Wawruch study [7], which analyzed 600 patients aged ≥65 years in an internal medicine ward, the prevalence of polypharmacy (six or more drugs) at admission was 60%, increasing to 62% at discharge. Another study [8] found that among 543 patients aged ≥75 admitted to selected internal medicine wards, 58% were taking more than six different medications. In another study, 57% of 2,465 elderly patients admitted to geriatric and internal medicine wards were using more drugs at discharge than in the month before admission [6]. Our analysis showed that nearly 40% of 1,155 elderly patients discharged to home who at admission were taking fewer than five different medicines had shifted to polypharmacy at discharge. On average, they were taking five drugs at admission and six at discharge, thus fewer than in other studies, which reported an average of six and seven drugs at admission and discharge, respectively [6, 8].

Antithrombotic agents were the most prescribed drugs both at admission and at discharge in our study, followed by drugs for peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), high-ceiling diuretics, and ACE inhibitors. Drugs for peptic ulcer and GERD showed the largest increase at discharge, shifting from 41% at admission to 56%. This might indicate an area of inappropriate prescribing that was specifically assessed in an ad hoc analysis [36] in which >60% of patients receiving these drugs had no specific indication for their use. Predictors of polypharmacy in hospital in-patients have been examined only in a few studies [6, 7], which indicated different sociodemographic and clinical factors such as age, sex, living alone, multiple pathologies, and some specific chronic diseases (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, CVD, and COPD). We, too, found that age, number of drugs at admission, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and COPD were predictors of polypharmacy at discharge. As in other studies [6–8], the results of our study indicate that several cardiovascular chronic diseases at admission should be considered a predictor of polypharmacy at discharge because the worsening of these chronic disorders might justify the prescription of new drugs over and above previous home therapy. Furthermore, clinicians might add new drug therapies at discharge to manage the conditions that led to hospital admission or to “prevent” some disease or drug-related risk, such as gastroprotective agents for patients taking aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or polypharmacy itself. Another reason for polypharmacy is often the need to treat some chronic condition, such as diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, according to the guidelines for each disease. In many cases, guidelines for each specific disease support the need to prescribe more than one drug, but only in a few cases do they take into account the patient’s comorbidities and the number and type of drugs taken at the time of the study [10, 21, 27–29, 37].

Although the absolute number of drugs cannot be considered a direct indicator of prescribing appropriateness [38], there is growing evidence that polypharmacy is associated with increases in many adverse outcomes, including adverse drug reactions, drug–drug or drug–disease interactions, falls, hospital admission, and mortality [3, 4, 16, 20, 29]. Moreover, although analysis of the appropriateness of drug prescribing was not the aim of our study, we stress the importance of reviewing drug regimens for older persons in hospital taking multiple medications, as discussed in the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) quality indicators for appropriate drug [39]. However, considering the small proportion of enrolled patients whose medications at discharge were fewer than at admission, our study seems to suggest that hospitalization fails as an important step for reviewing patient’s drug regimens and that clinicians still prefer a disease-oriented approach [28, 29].

Length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality

One study found that the number of drugs used at hospital admission was related to the number of drug-related problems while in hospital. The risk of a drug-related problems increased with each additional drug supplied in hospital. This linear relationship was present over the entire range of drugs, without any specific number [9]. To our knowledge, only one report analyzed the relationship between polypharmacy and length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality [8]. This study, too, found that polypharmacy was not related to the length of hospital stay or in-hospital mortality. We also found, as expected, that the occurrence of AEs in hospital was the most significant predictor for these outcomes, prolonging hospital stay by nearly 4 days and raising the risk of in-hospital death sevenfold. Only a case of suspected adverse drug reaction was reported by clinicians. This low rate is probably due to the lack of an explicit request to signal ADRs and to the well-known underreporting by physicians of suspected ADRs. Although common consequences of polypharmacy include ADRs that can negatively influence outcomes, an account of the restricted window of observation during hospital stay or the “diluted effect” of the number of prescribed drugs was probably the reason we found no effects of polypharmacy on the major clinical outcomes. Furthermore, polypharmacy may be unavoidable and appropriate in some patients, especially when it is carefully prescribed and monitored.

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of the REPOSI study are, first, its multicenter design, which involved 38 internal medicine and geriatric wards throughout Italy, resulting in a sample representation of the hospitalized elderly population, Second, patients were enrolled in four different weekly periods (one per season) to balance the effect of seasons on acute diseases leading to hospital admission. However, there were some limitations to our study. First, problems can arise when using hospital data for research, because hospital records are not designed for research purposes but for patient care, and their diagnostic quality may vary depending upon each hospital, physician, and clinical unit, as data on disability and cognitive status are not routinely collected from these sources. Moreover, admissions are often selective on the basis of local characteristics, associated medical conditions, and admissions policies, which can vary from hospital to hospital. Second, the data set was not planned to include multidimensional geriatric assessment because that is not a general practice in internal medicine wards. Thus, we have no information on patients’ functional profiles. Third, the study allowed no general conclusion regarding the number of drugs taken before admission or on the appropriateness of the drugs already prescribed. Also, over-the-counter drugs and herbal medicines taken before admission were not included.

Conclusions

Although published studies on polypharmacy did not all use the same cutoff point, undoubtedly, elderly in-patients are exposed to a large number of drugs, often due to chronic conditions, and hospitalization often leads to a significant increase in the number of medications. When assessing the risk of polypharmacy, clinicians should carefully consider the patient’s age, the number and type of drugs at admission, and the presence of any chronic disease such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or COPD. At discharge, the presence of polypharmacy and an increase in the number of drugs should alert clinicians to carefully review each patient’s drug portfolio with the aim of withdrawing useless or inappropriate medications. Last but not least, the occurrence of an AE in hospital should raise the level of clinical monitoring for the patient, because AEs are strongly related to the risk of prolonging hospital stay or in-hospital mortality.

References

Gurwitz JH (2004) Polypharmacy. A new paradigm for quality drug therapy in the elderly? Arch Intern Med 164:1957–1959

Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT (2007) Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 5:345–351

Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D (2009) The effects of polypharmacy in older adults. Clin Pharmacol Therapeutics 85:86–98

Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE et al (2006) Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 54:1516–1523

Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosemberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA (2002) Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the united State: the Slone survey. JAMA 287:337–344

Corsonello A, Pedone C, Corica F, Antonelli Incalzi R, on behalf of the Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza (GIFA) investigators (2007) Polypharmacy in the elderly patients at discharge from the acute care hospital. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 3:197–203

Wawruch M, Zikavska M, Wsolova L, Kuzelova M, Tisonova J, Gajdosik J et al (2008) Polyphramacy in elderly hospitalised patients in Slovakia. Pharm World Sci 30:235–242

Schuler J, Duckelmann C, Beindl W, Prinz E, Michalski T, Pichelr M (2008) Polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing in elderly internal medicine patients in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr 120:733–741

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A (2006) Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol 63:187–195

Milton JC, Hill-Smith I, Jackson SHD (2008) Prescribing for older people. BMJ 336:606–609

Simonson W, Feinberg JL (2005) Medication-related problems in the elderly. Defining the issues and identifying solutions. Drug Aging 22:559–569

Veehof LJG, Stewart RE, Haaijer-Raskamp FM, Meyboom-de Jong B (2000) The development of polypharmacy. A longitudinal study. Fam Pract 17:261–267

Linjakumpu T, Hartkainen S, Klaukka T, Veijola J, Kivela SL, Isoaho R (2002) Use of medications and polypharmacy are increasing among elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 55:809–817

Koh Y, Kutty FBM, Li SC (2005) Drug-related problems in hospitalized patients on polypharmacy: the influence of age and gender. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 1:39–48

Lund BC, Camahan RM, Egge JA, Chrischilles EA, Kaboli PJ 2010 Inappropriate prescribing predicts adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Pharmacother. doi:10.1345/aph.1M657

Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N et al (2007) Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet 370:173–184

Veehof LJG, Meyboom-de Jong B, Haaijer-Raskamp FM (2000) Polypharmacy in the elderly-a literature review. Eur J Gen Pract 6:98–106

Jyrkka J, Enlund H, Korhonen MJ, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S (2009) Polypharmacy stauts as an indicator of mortality in an elderly population. Drugs Aging 26:1039–1048

Onder G, Pedone C, Landi F, Cesari M, Vedova C, Bernabei R et al (2002) Adverse drug reactions as cause of hospital admission: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA). J Am Geriatr Soc 50:1962–1968

Onder G, Landi F, Liperoti R, Fialova D, Gambassi G, Bernabei R (2005) Impact of inappropriate drug use among hospitalized older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 61:1453–1459

Bressler R, Bahl JJ (2003) Principles of drug therapy for the elderly patients. Mayo Clin Proc 78:1564–1577

van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Knottnerus JA (1996) Comorbidity or multimorbidity: what’s in a name? A review of literature. Eur J Gen Pract 2:65–70

van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF et al (1998) Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 51:367–375

Verbrugge LM, Lepkowski JM, Imanaka Y (1989) Comorbidity and its impact on disability. Milbank Q 67:450–484

Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, van den Bos GA (2001) Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. J Clin Epidemiol 54:661–674

Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G (2002) Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 162:2269–2276

Boyd CM, Ritchie CS, Tipton EF, Studenski SA, Wieland D (2008) From bedside to bench: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research conference on comorbidity and multiple morbidity in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res 20:181–188

Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Agostini JV (2004) Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med 351:2870–2874

Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C et al (2005) Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA 294:716

Creditor MC (1993) Hazard of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med 118:219–223

World Health Organization (1987) International Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death. Ninth Revision (ICD-9). Geneva: World Health Organization. http://icd9cm.chrisendres.com/. Accessed 12 July 2010

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

World Health Organization. Guidelines for ATC Classification. Sweden, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Norway and Nordic Councils on Medicines, 1990

Bernardini B, Meinecke C, Zaccarini C, Bongiorni N, Fabbrini S, Gilardi C, Bonaccorso O, Guaita A (1993) Adverse clinical events in dependent long-term nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 41:105–111

Bellelli G, Frisoni GB, Barbisoni P, Beffelli S, Rozzini R, Trabucchi M (2001) The management of adverse clinical events in nursing homes: a 1-years survey study. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:915–925

Pasina L, Nobili A, Tettamanti M, Salerno F, Corrao S, Bonazzi J, Vicidomini R, Mannucci PM (2009) A nome del partecipanti al Progetto Registro Politerapie SIMI. Utilizzo e appropriatezza d’uso dei farmaci anti-ulcera peptica/reflusso gastroesofageo in una coorte di anziani ricoverati in reparti di medicina interna. Intern Emerg Med 4:S69

Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL (1998) The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Eng J Med 338:1516–1520

Holmes HM (2009) Rational prescribing for patients with a reduced life expectancy. Clin Pharmacol Therapeutics 85:103–107

Knight EL, Avorn J (2001) Quality indicators for appropriate medication use in vulnerable elders. Intern Med 135:703–710

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Farncesco Violi, President of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine, for his help and encouragement. We are grateful to Judith Baggott for editorial assistance.

Financial disclosure

Carlotta Franchi holds a fellowship granted by Rotary Clubs Milano Naviglio Grande San Carlo, Milano Scala and Inner Wheel Milano San Carlo.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that no conflict of interest exist. All the authors state that they have a full control of data and that they agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Funding sources

Nothing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

SIMI, Italian Society of Internal Medicine. Participating hospitals and coauthors are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Appendix

Appendix

REPOSI collaborators and participating units

The following hospital and investigators contributed to this study: Pier Mannuccio Mannucci, Alberto Tedeschi, Raffaella Rossio (Medicina Interna 2, Fondazione IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore, Milano); Guido Moreo, Barbara Ferrari (Medicina Interna 3, Fondazione IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore, Milano); Cesare Masala, Antonio Mammarella, Valeria Raparelli (Medicina Interna, Università La Sapienza, Roma); Nicola Carulli, Stefania Rondinella, Iolanda Giannico (Medicina Metabolica, Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia); Leonardo Rasciti, Silvia Gualandi (Medicina Interna, Policlinico S. Orsola Malpighi, Bologna); Valter Monzani, Valeria Savojardo (Medicina d’Urgenza, IRCCS Fondazione Ospedale Maggiore, Milano); Maria Domenica Cappellini, Giovanna Fabio, Flavio Cantoni (Medicina Interna 1A, Fondazione IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore, Milano); Franco Dallegri, Luciano Ottonello, Alessandra Quercioli, Alessandra Barreca (Medicina Interna 1, Università di Genova); Riccardo Utili, Emanuele Durante-Mangoni, Daniela Pinto (Medicina Interna, Seconda Università di Napoli); Roberto Manfredini, Elena Incasa, Emanuela Rizzioli (Medicina Interna, Azienda USL, Ferrara); Massimo Vanoli, Gianluca Casella (Medicina Interna, Ospedale di Lecco, Merate); Giuseppe Musca, Olga Cuccurullo (Medicina Interna, P.O. Cetraro, ASP Cosenza); Laura Gasbarrone, Giuseppe Famularo, Maria Rosaria Sajeva (Medicina Interna, Ospedale San Camillo Forlanini, Roma); Antonio Picardi, Dritan Hila (Medicina Clinica-Epatologia, Università Campus Bio-Medico, Roma); Renzo Rozzini, Alessandro Giordano (Fondazione Poliambulanza, Brescia); Andrea Sacco, Antonio Bonelli, Gaetano Dentamaro (Medicina, Ospedale Madonna delle Grazie, Matera); Francesco Salerno, Valentina Monti, Massimo Cazzaniga (Medicina Interna, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, Università di Milano); Ingrid Nielsen, Piergiorgio Gaudenzi, Lisa Giusto (Medicina ad Alta Rotazione, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria, Ferrara); Enrico Agabiti Rosei, Damiano Rizzoni, Luana Castoldi (Clinica Medica, Università di Brescia); Daniela Mari, Giuliana Micale (Medicina Generale ad indirizzo Geriatrico, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milano); Emanuele Altomare, Gaetano Serviddio, Santina Salvatore (Medicina Interna, Università di Foggia); Carlo Longhini, Cristian Molino (Clinica Medica, Azienda Mista Ospedaliera Universitaria Sant’Anna, Ferrara); Giuseppe Delitalia, Silvia Deidda, Luciana Maria Cuccuru (Clinica Medica, Azienda Mista Ospedaliera Universitaria, Sassari); Giampiero Benetti, Michela Quagliolo, Giuseppe Riccardo Centenaro (Medicina 1, Ospedale di Melegnano, Vizzolo Predabissi, Milano); Alberto Auteri, Anna Laura Pasqui, Luca Puccetti (Medicina Interna, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Le Scotte, Siena); Carlo Balduini, Giampiera Bertolino, Piergiorgio Cavallo (Dipartimento di Medicina Interna, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Università degli Studi di Pavia); Esio Ronchi, Daniele Bertolini, Nicola Lucio Liberato (Medicina Interna, Ospedale Carlo Mira, Casorate Primo, Pavia); Antonio Perciccante, Alessia Coralli (Medicina, Ospedale San Giovanni-Decollato-Andisilla, Civita Castellana); Luigi Anastasio, Leonardo Bertucci (Medicina Generale, Ospedale Civile Serra San Bruno); Giancarlo Agnelli, Ana Macura, Alfonso Iorio, Maura Marcucci (Medicina Interna e Cardiovascolare, Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia, Università di Perugia); Cosimo Morabito, Roberto Fava (Medicina, Ospedale Scillesi d’America, Scilla); Giuseppe Licata, Antonino Tuttolomondo, Riccardo Di Sciacca (Medicina Interna e Cardioangiologia, Università degli Studi di Palermo); Luisa Macchini, Anna Realdi (Clinica Medica 4, Università di Padova); Luigi Cricco, Alessandra Fiorentini, Cristina Tofi (Geriatria, Ospedale di Montefiascone); Carlo Cagnoni, Antonio Manucra (UO Medicina e Primo Soccorso, Ospedale di Bobbio, Azienda USL di Piacenza); Giuseppe Romanelli, Alessandra Marengoni, Francesca Bonometti (UO Geriatria, Spedali Civili di Brescia); Michele Cortellaro, Maria Rachele Meroni, Marina Magenta (Medicina 3, Ospedale Luigi Sacco, Università di Milano); Carlo Vergani, Dionigi Paolo Rossi (Geriatria, Fondazione IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore e Università di Milano).

Clincal data monitoring and revision: Valentina Spirito, Damia Noce, Jacopo Bonazzi, Rossana Lombardo, Luigi De Vittorio (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”, Milano).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nobili, A., Licata, G., Salerno, F. et al. Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. The REPOSI study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67, 507–519 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-010-0977-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-010-0977-0