Abstract

The stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of adipose tissue contains an abundant population of multipotent adipose-tissue-derived stem cells (ASCs) that possess the capacity to differentiate into cells of the mesodermal lineage in vitro. For cell-based therapies, an advantageous approach would be to harvest these SVF cells and give them back to the patient within a single surgical procedure, thereby avoiding lengthy and costly in vitro culturing steps. However, this requires SVF-isolates to contain sufficient ASCs capable of differentiating into the desired cell lineage. We have investigated whether the yield and function of ASCs are affected by the anatomical sites most frequently used for harvesting adipose tissue: the abdomen and hip/thigh region. The frequency of ASCs in the SVF of adipose tissue from the abdomen and hip/thigh region was determined in limiting dilution and colony-forming unit (CFU) assays. The capacity of these ASCs to differentiate into the chondrogenic and osteogenic pathways was investigated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and (immuno)histochemistry. A significant difference (P = 0.0009) was seen in ASC frequency but not in the absolute number of nucleated cells between adipose tissue harvested from the abdomen (5.1 ± 1.1%, mean ± SEM) and hip/thigh region (1.2 ± 0.7%). However, within the CFUs derived from both tissues, the frequency of CFUs having osteogenic differentiation potential was the same. When cultured, homogeneous cell populations were obtained with similar growth kinetics and phenotype. No differences were detected in differentiation capacity between ASCs from both tissue-harvesting sites. We conclude that the yield of ASCs, but not the total amount of nucleated cells per volume or the ASC proliferation and differentiation capacities, are dependent on the tissue-harvesting site. The abdomen seems to be preferable to the hip/thigh region for harvesting adipose tissue, in particular when considering SVF cells for stem-cell-based therapies in one-step surgical procedures for skeletal tissue engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tissue engineering is an emerging field in modern medicine. Therapies involve the combination of cells and scaffold materials that can be loaded with bioactive factors, ideally resulting in the regeneration or replacement of lost or damaged tissues and organs. Multiple cell sources have been investigated for their possible applicability in tissue engineering. Embryonal stem cells are the most potent stem cells; however, their use is controversial and has mayor ethical considerations (Dresser 2001). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be obtained from the adult and are widely used because of their differentiation potential. In addition to bone marrow, periosteum (Nakahara et al. 1991), muscle (Asakura et al. 2001), and adipose tissue (Zuk et al. 2002) also appear to be sources of MSCs.

Subcutaneous adipose tissue is a particularly attractive reservoir of progenitor cells, because it is easily accessible, abundant, and self-replenishing. It is derived from the mesodermal germ layer and contains a supportive stromal vascular fraction (SVF) that can be readily isolated (Gronthos et al. 2003; Zuk et al. 2001). This SVF from adipose tissue consists of a heterogeneous mixture of cells, including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, pericytes, leukocytes, mast cells, and pre-adipocytes (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006; Peterson et al. 2005; Prunet-Marcassus et al. 2005). In addition to these cells, the SVF contains an abundant population of multipotent adipose-tissue-derived stem cells (ASCs) that possess the capacity to differentiate into cells of mesodermal origin in vitro, e.g., adipocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and (cardio)myocytes (Erickson et al. 2002; Guilak et al. 2004; Halvorsen et al. 2001; Hattori et al. 2004; Planat-Benard et al. 2004; Rangappa et al. 2003; Zuk et al. 2001). Because of these favorable characteristics, interest has been growing in the application of ASCs for cell-based therapies such as tissue engineering.

For clinical practice, an advantageous approach would be to harvest ASCs and immediately give them back to the patient within the same operation, the so called “one-step surgical procedure” (Helder et al. 2007). This overcomes long-lasting culture expansion of ASCs on the one hand, but necessitates the use of the SVF of adipose tissue on the other hand, since fast selection procedures for stem cells in the SVF are not yet available. Therefore, the success of this procedure requires SVF-isolates to contain sufficient ASCs capable of differentiating into the desired cell lineage. In view of this, we have previously investigated the effect of three different surgical procedures for the harvesting of adipose tissue, i.e., resection, tumescent or conventional liposuction, and ultrasound-assisted liposuction, on the yield and function of the stem cells. We have demonstrated that the SVF isolates from adipose tissue harvested by ultrasound-assisted liposuction contain fewer stem cells, and that the stem cells have a longer population doubling time, leading us to conclude that resection and tumescent liposuction are preferable to ultrasound-assisted liposuction for harvesting adipose tissue, if the cells are to be used for tissue-engineering purposes (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006).

In the present study, we have investigated whether the yield and functional characteristics of ASCs in the SVF are affected by the most frequently used adipose-tissue-harvesting sites. We have previously demonstrated that the yield of nucleated cells in the SVF of the adipose tissue from these different tissue-harvesting sites is similar (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006). In the current study, the frequency of ASCs in the SVF cell isolates has been determined by using limiting dilution and colony-forming unit (CFU) assays. In addition, we have investigated the frequency of CFUs showing an osteogenic differentiation capacity. SVF cells have been subsequently cultured in order to obtain homogeneous cell populations and to acquire sufficient cells to determine their chondrogenic differentiation potential in micromass cultures. Homogeneity has been checked by determining the growth kinetics and phenotypic characteristics of the ASCs. To verify the maintenance of multidifferentiation potential, osteogenic and chondrogenic induction has been assessed in these homogeneous ASC cultures.

Materials and methods

Donors

Samples of human subcutaneous adipose tissue were obtained as waste material after elective tumescent liposuction or resection and donated after informed consent from healthy donors operated on at the Departments of Plastic Surgery of two clinics in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Adipose tissue was taken from the abdomen (n = 12) and the hip/thigh region (n = 10) during cosmetic surgery; 22 female donors were included in this study. The average age (mean age 40, range 24–62 years) and body mass index (BMI; mean BMI 25.5; range 22.2–29.6 kg/m2) were similar for both groups (Table 1).

Cell isolation and storage

Isolation of the SVF from adipose tissue was performed as previously described (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006). The isolation protocol included a Ficoll density centrifugation step to remove contaminating erythrocytes. After isolation, 4×106 SVF cells were resuspended in a mixture (1:1) of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and cryoprotective medium (Freezing Medium, BioWhittaker, Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium), frozen under “controlled rate” conditions in a Kryosave (HCI Cryogenics, Hedel, The Netherlands), and stored in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen according to standard practice at the Department of Pathology of the VU University Medical Center and following the guidelines of current Good Manufacturing Practice.

Limiting dilution assay

To assess the frequency of ASCs in the SVF of adipose tissue, SVF cells were seeded in normal culture medium, consisting of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Gibco, Calif., USA) in 96-well plates at 15×103 cells/well in the upper row. Two-fold dilution steps of the cells were made in subsequent rows. All cultures were performed in duplicate. Medium was changed twice a week. After 3 weeks, each well was individually scored for the number of cells. A well containing a cluster of at least 10 adhered fibroblast-like cells was considered as being positive. The frequency of ASCs was calculated from the rows of cells for which 25%–75% of the wells were scored as positive.

CFU assays

CFU assays were performed to check the consistency of the limiting dilution assay method and to determine the frequency of CFU capable of differentiating into the osteogenic lineage from the abdomen (n = 7) and hip/thigh region (n = 6). SVF cells were resuspended in normal culture medium, consisting of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Gibco). Two 6-well plates were prepared in which the SVF was diluted ten-fold across both columns, resulting in a upper column containing 104 and a lower column containing 103 nucleated SVF cells.

For the CFU-fibroblast (CFU-F) assay, the fixation time was 11–14 days, depending on the amount and growth kinetics of the colonies (merging of colonies was avoided). At the appropriate time point, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min, and subsequently colored in a 0.2% toluidine blue solution in borax buffer for about 1 min. Excess stain was washed off with distilled water, and colonies were counted.

Cells of the duplicate 6-well plate were submitted to a CFU-alkaline phosphatase (CFU-ALP) assay. Cultures were performed in normal medium for 7 days in order to obtain colonies and to remove contaminating cells, after which osteogenic medium was added for 2 weeks. Following this period, cells in the CFU-ALP plate were rinsed with PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and incubated for 10 min in a 0.2 M TRIS-hydrochloride (pH 10), 0.2 M calcium chloride, 0.1 M magnesium chloride solution, whereafter a solution containing 0.2 M TRIS-hydrochloride (pH 10), 0.2 M calcium chloride, 0.1 M magnesium chloride, and 600 μl nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate was added for 30 min. The percentage of the colonies staining positive for ALP was determined.

Culturing of SVF cells

ASCs from the abdomen and hip/thigh region were cultured up to passage 2 for an adequate and quantitative comparison of stem-cell proliferation and differentiation capacity. Single-cell suspensions of cryopreserved SVF cells were seeded at 5.0×106 nucleated cells/cm2 in normal culture medium. The cultures were maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere. The medium was changed twice a week. When reaching 80%–90% confluency, cells were detached with 0.5 mM EDTA/0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen) for 5 min at 37°C and replated. Cell viability was assessed by using the trypan blue exclusion assay. A homogeneous population of ASCs was thus obtained from abdomen and hip/thigh region and was subsequently checked by determining growth kinetics and by analyzing the surface-marker expression profile of the ASCs.

Growth kinetics of ASCs

To determine the growth kinetics of cultured ASCs, ten T25 flasks per donor were seeded with 1×105 cultured ASCs (passage 2 or 3). At several time points (between days 2 and 12) after seeding, cells from two duplicate flasks were harvested and counted. ASC numbers were plotted against the number of days cultured, and the exponential growing phase of the cells was determined. The population doubling time was calculated by using the formula:

where N1 was the number of cells at the beginning of the exponential growing phase, and N2 was the number of cells at the end of the exponential growing phase.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of cultured ASCs from abdomen and hip/thigh region were phenotypically characterized by using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson, USA) as previously described (Varma et al. 2007). All monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were of the immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) isotype. Cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies (conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin, or allophycocyanin) against CD31, CD34, CD45, CD54, CD90, CD106, HLA-DR, and HLA-ABC (BD Biosciences, San José, Calif.), CD166 (RDI Research Diagnostics, Flanders, N.J.), CD105 (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.), CD117 (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.), and CD146 (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.). Nonspecific fluorescence was determined by incubating the cells with conjugated mAb anti-human IgG1 (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark).

Chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation

The chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation capacities of the cultured ASCs from the abdomen (n = 4) and hip/thigh region (n = 4) were studied. Chondrogenic differentiation was induced in cultured ASCs as previously described, with some modifications (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006). In short, a 50-μl drop of a concentrated ASC cell suspension (8×106cells/ml, passage 2) was applied to a glass slide and allowed to attach at 37°C for 1 h. Then, 750 μl chondrogenic medium, consisting of DMEM, plus ITS+ Premix (final concentration in medium when diluted 1:100 was 6.25 μg/ml insulin, 6.25 μg/ml transferrin, 6.25 ng/ml selenous acid, 1.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5.35 μg/ml linoleic acid; BD, USA), 10 ng/nl transforming growth factor- β1 (TGF-β1; Biovision, ITK-diagnostics), 1% FCS, 25 μM ascorbate-2-phosphate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine, was overlaid gently. Cells were maintained in a 5% CO2/1% oxygen custom-designed hypoxia workstation (T.C.P.S. Rotselaar, Belgium) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere, as this was shown to enhance chondrogenic differentiation (data not shown). Chondrogenic media were changed every 2–3 days.

For osteogenic differentiation, ASCs (passage 2) were seeded at 5000 cells/cm2 and cultured in monolayer in osteogenic medium, consisting of normal culture medium supplemented with 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 50 μg/ml ascorbate-2-phosphate, and 100 ng/ml bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2, Peprotech EC, London, UK). Osteogenic medium was changed twice a week.

(Immuno)histochemistry

(Immuno)histochemistry was performed as described previously (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006). Cell nodules that formed under chondrogenic culture conditions were stained with Alcian blue (Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) at acidic pH for detection of proteoglycans. For the detection of collagen Type II, staining was performed with mouse monoclonal antibody II-II6B3 (1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa, USA) against human collagen Type II in PBS containing 1% BSA.

Osteogenesis was visualized after 21 days of culture in osteogenic medium by Von Kossa staining to establish the formation of a calcified matrix, typical for mature osteoblasts. The protocol used was as described previously (Varma et al. 2007) with only one modification of counterstaining the cytoplasm of the cells using fast green. Calcified extracellular matrix was visualized as black spots.

Spectrophotometric ALP activity

Early differentiation of MSCs into immature osteoblasts is characterized by ALP enzyme activity, with human MSCs expressing ALP as early as 4 days after induction, and maximum levels being observed at around 14 days after induction (Jaiswal et al. 1997). Therefore, cellular ALP activity was measured after culturing the ASCs in osteogenic medium for 14 days. Cells were lysed with distilled water, and the ALP activity and protein content were determined. To determine ALP activity, p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at pH 10.3 was used as the substrate, as described by Lowry (1955). ALP activity was expressed as micromole per microgram of protein in the cell layer. The amount of protein was determined by using a BCA Protein Assay reagent Kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill., USA), and the absorbance was read at 540 nm with a microplate reader (Biorad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif., USA).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA isolation and reverse transcription were performed as previously described (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006). Real-time polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were performed by using the SYBRGreen reaction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Diagnostics) in a LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics). cDNA (approximately 5 ng) was used in a volume of 20 μl PCR mix (LightCycler DNA Master Fast Startplus Kit, Roche Diagnostics) containing a final concentration of 0.5 pmol primers. Relative housekeeping gene expression for 18 S-rRNA (18 S) and relative target gene expression for aggrecan (AGG), collagen Type II (COL2B), and collagen Type X (COL10α1) regarding chondrogenic differentiation, and for collagen Type I (COL1α), osteopontin (OPN), and runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX-2) regarding osteogenic differentiation were determined.

Primers (Invitrogen) used for real-time PCR are listed in Table 2. They were designed by using Clone Manager Suite software program version 6 (Scientific & Educational Software, Cary, N.C., USA). The amplified PCR fragment extended over at least one exon border, based on homology in conserved domains between human, mouse, rat, dog, and cow, except for the 18 S gene (encoded by one exon only). Amplified Col2B PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. For real-time PCR, the values of relative target gene expression were normalized to relative 18 S housekeeping gene expression.

Real-time PCR data analysis

With the Light Cycler software (version 4), the crossing points were assessed and plotted versus the serial dilution of known concentrations of the standards derived from each gene by the Fit Points method. PCR efficiency was calculated by Light Cycler software, and the data were used only if the calculated PCR efficiency was between 1.85–2.0.

Statistics

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used to determine the normalcy of measurements and, if appropriate, their logarithmics. For the evaluation of yield and growth kinetics, means between two groups in one variable were compared by using the independent sample two-tailed t-test. Partial correlation was expressed as the Pearson correlation coefficient, r. For evaluation of gene expression, a repeated measures analysis of variance was used to determine significant differences when increasing time-points in one donor within one variable were compared. If levels of gene expression were below the detection limit (0.05), values were set at 10−2 (or log level at −2). All statistical tests used a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

Effects of tissue-harvesting site on frequency of ASCs

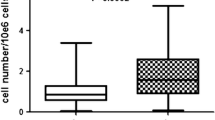

In a previous study, we demonstrated that the yield of nucleated cells in the SVF of adipose tissue from different tissue-harvesting sites was similar (Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006). To investigate whether the tissue-harvesting site affected the frequency of ASCs in the SVF in the present study, limiting dilution and CFU-F assays were performed. The outcomes of both types of assays were similar (Fig. 1a, b). When combined, the SVF of adipose tissue harvested from the abdomen contained 5.1 ± 1.1% ASCs (mean ± SEM), whereas the percentage of ASCs in the SVF of adipose tissue harvested from the hip/thigh region was much lower (1.2 ± 0.7%; Fig. 1c). This difference in ASC frequency between adipose tissue from the abdomen and hip/thigh region was significant (P = 0.0009).

Effect of adipose-tissue-harvesting site on the frequency of adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) in the stromal vascular fraction (SVF). After isolation of the SVF from adipose tissue of both tissue-harvesting sites, the frequency of ASCs in the SVF isolates was determined by using: (a) a limiting dilution assay (LD) and (b) a colony-forming unit (CFU) assay (CFU-F), with similar results. When combined (c), a significant difference was detected in ASC frequency between adipose tissue harvested from the abdomen and adipose tissue harvested from the hip/thigh region (P-values: a limiting dilution: P = 0.003, b colony-forming unit: P = 0.05, c combined: P = 0.0009)

Effect of tissue-harvesting site on frequency of CFUs having osteogenic differentiation potential

Parallel to the CFU-F assay (Fig. 1b), CFU-ALP assays were also performed to determine the percentage of the CFUs capable of osteogenic differentiation. For adipose tissue from the abdomen, 54.9 ± 12.1% (mean ± SEM) of the CFUs stained positive for ALP, whereas the CFUs from adipose tissue of the hip/thigh region displayed an ALP positivity of 72.8 ± 8.1% (Fig. 2). Apparently, no differences in osteogenic potential existed between ASCs from the two tissue-harvesting sites (P = 0.43).

Phenotypic characterization and growth kinetics of cultured ASCs

Cultured ASCs (passages 2 to 4) from abdomen and hip/thigh regions were phenotypically characterized. ASCs from both tissue-harvesting sites were demonstrated to be homogeneous populations staining positive for stem-cell-associated markers CD34, CD54, CD90, CD105, CD166, and HLA-ABC, and negative for hematopoietic/leukocytic/endothelial markers such as CD31, CD45, CD106, CD146, and HLA-DR (Table 3).

To determine growth kinetics, the population doubling time of ASCs from passages 2 to 3 was determined. When ASCs numbers were monitored over time, a cell growing curve was obtained showing an exponential growing phase, after which the cells reached confluency (Fig. 3a,b). The mean population doubling time of the ASCs in the exponential growing phase was about 2 days when the adipose tissue was harvested from the abdomen and hip/thigh regions (abdomen: 2.1 ± 0.8; hip/thigh: 2.3 ± 0.3; mean ± SEM; Fig. 3c).

Effect of the adipose-tissue-harvesting site on growth kinetics of ASCs in vitro. a Growth kinetics of ASCs of a representative donor when adipose tissue was harvested from the abdomen. b Growth kinetics of ASCs when adipose tissue was harvested from the hip/thigh region. c Population doubling time was calculated from the exponential growing phase of the cells. There was no significant difference in population doubling time of ASCs from the abdomen and hip/thigh region (P = 0.78, independent Student t-test).

Effect of tissue-harvesting site on osteogenic differentiation potential of ASCs

Differentiation of cultured ASCs into the osteogenic lineage was induced by culturing the cells in monolayer in osteogenic medium containing BMP-2. Specific RNA expression of osteogenically induced ASCs from all donors tested increased over time, RUNX-2 being up-regulated 18-fold (P = 0.002) and COL1α being up-regulated seven-fold (P = 0.024) after 7 days (Fig. 4a,b). OPN gene expression was increased after 7 days; however, this increase was not significant (Fig. 4c). No significant differences were detected in osteogenic gene expression between ASCs derived from the abdomen and ASCs derived from the hip/thigh region, at all three time points tested.

Effect of adipose-tissue-harvesting site on the osteogenic differentiation of cultured ASCs in vitro. a–c RUNX-2 (runt-related transcription factor 2; P = 0.002), COL1α1 (collagen type Ia; P = 0.024), and OPN (osteopontin; P = 0.38) gene expression was measured after 0, 4, and 7 days (d) of osteogenic induction, by using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). No significant differences were detected in osteogenic gene expression between ASCs derived from the abdomen and ASCs derived from the hip/thigh region, at all three time points tested. d ALP activity was significantly increased after 14 days in the osteogenically stimulated cells (stim) compared with that in unstimulated cells (con; P = 0.047). No statistically significant difference was apparent in ALP activity between ASCs derived from abdominal fat and ASCs from hip/thigh fat. e–g Von Kossa staining of ASCs from abdomen (e) and hip/thigh region (f) after 21 days of culture in osteogenic medium and in control medium (g), showing mineralized matrix visible as black spots.

ALP activity in the ASCs was measured after 14 days of osteogenic stimulation. ASCs cultured in control medium served as negative controls. ALP activity in the osteogenically stimulated cells was significantly increased (P = 0.047) compared with that in control cells (Fig. 4d). No statistically significant difference was apparent in ALP activity between ASCs derived from abdominal fat and ASCs from hip/thigh fat. Calcification of the osteogenic matrix was confirmed by using Von Kossa staining; black spots could be observed after 3 weeks of osteogenic stimulation of ASCs from both origins (Fig. 4e: abdomen, Fig. 4f: hip/thigh). No calcification was seen in ASC cultures expanded in control medium (Fig. 4g).

Effect of tissue-harvesting site on chondrogenic differentiation potential of ASCs

The chondrogenic differentiation potential of ASCs was analyzed after culturing the cells in a micromass in chondrogenic medium containing TGF-β. Within 24 h of culture, most of the cells formed nodules (n = 7).

PCR-amplified COL2B mRNA expression was detectable but not quantifiable after 7 days in ASCs from both the abdomen and hip/thigh region in most but not all donors (n = 5). As shown in Fig. 5a, cells from both tissue-harvesting sites displayed COL2B mRNA. Under non-chondrogenic conditions, no COL2B could be detected. AGG and COL10α1 mRNA expression in all donors tested increased over time, AGG being up-regulated 2.4-fold (P = 0.041) at day 7 when compared with day 4, and COL10α1 being up-regulated four-fold (P = 0.024) after 7 days (Fig. 5b,c). No significant differences were detected in chondrogenic gene expression between ASCs derived from the abdomen and ASCs derived from the hip/thigh region, at all three time points tested.

Effect of the tissue-harvesting site on the chondrogenic differentiation of cultured ASCs in vitro. a Both abdomen (lane 1) and hip/thigh region (lane 2) display COL2B mRNA. Under nonchondrogenic conditions, no COL2B could be detected (lane 3). b, c Aggrecan (AGG; P = 0.041) and collagen 10A (Col10a; P = 0.024) gene expression, respectively, was up-regulated after 7 days (d), as measured by qRT-PCR. No significant differences were detected in chondrogenic gene expression between ASCs derived from the abdomen and ASCs derived from the hip/thigh region, at all three time points tested. d, f Cartilaginous matrix expression was visualized in both tissue-harvesting sites by staining proteoglycans (Alcian blue) and COL2 (Col2-II6B3 antibody), respectively. e At higher magnification, the ASC nodules resembled cartilage-like tissue, composed of spherical cells surrounded by lacunae and lying in a proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix.

Alcian blue staining demonstrated proteoglycan deposition in the ASC nodules from both the hip/thigh region and abdomen (Fig. 5d). At higher magnification (Fig. 5e), the ASC nodules resembled cartilage-like tissue, composed of round cells, surrounded by lacunae and lying in a proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix that appeared positive for collagen Type II by immunostaining (Fig. 5f).

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated whether the yield and functional characteristics of ASCs are affected by the adipose tissue-harvesting site, i.e., abdomen and hip/thigh regions. We have found a difference in the frequency of ASCs between adipose tissue harvested from the abdomen and the hip/thigh regions. SVF isolates derived from abdominal fat contain significantly higher frequencies of ASCs. When cultured, the growth kinetics and surface-marker expression of ASCs from both tissue-harvesting sites are similar. We have detected no differences in osteogenic or chondrogenic differentiation potential between these cultured ASCs from the two tissue-harvesting sites.

Adipose tissue is a highly heterogeneous tissue, not only among individuals, but also when comparing different fat depots within one individual. Donor-dependent differences have been demonstrated to exist in (stem) cell yield, proliferation, and differentiation capacity, probably caused by differences in age (Hauner and Entenmann 1991; van Harmelen et al. 2003), BMI (Aust et al. 2004; Hauner et al. 1988; Jaiswal et al. 1997; van de Venter et al. 1994), and diseases such as osteoarthritis and diabetes (Barry 2003; Murphy et al. 2002; Ramsay et al. 1995). Donors used in this study for harvesting adipose tissue were healthy female donors up to 62 years old. Some patients who will benefit from tissue engineering of cartilage will be older or might suffer from disease, and males will also be affected. Therefore, future research should include these donor types to determine whether yields and functional characteristics are influenced by these variables.

In our donor population, no significant correlation has been detected between the frequency of ASCs and the age of the donor (P = 0.32, r = 0.27) or between the frequency of ASCs and BMI (P = 0.42, r = −0.22; data not shown). These data are in agreement with other studies that have demonstrated no correlation between BMI or age and numbers of ASCs per gram of adipose tissue (Hauner and Entenmann 1991; van Harmelen et al. 2003). Most importantly, this means that these variables cannot be responsible for the difference that we have found between the frequency of ASCs and the tissue-harvesting site.

In addition to donor-dependent heterogeneity, intra-individual differences between fat depots have been demonstrated, e.g., with regard to the metabolic response of adipose tissue to various hormonal and neurological stimuli (Guilak et al. 2004; Lacasa et al. 1997; Masuzaki et al. 1995; Monjo et al. 2003; Rodriguez-Cuenca et al. 2005) and the cellular composition of the adipose tissue (Peptan et al. 2006; Prunet-Marcassus et al. 2005). In this study, we have focused on the intra-individual differences in the yield and function of ASCs from two fat depots: the abdomen and the hip/thigh region. We have demonstrated that adipose tissue derived from the abdomen contains significant higher frequencies of stem cells compared with adipose from the hip/thigh region. Whereas SVF isolates from the abdomen in this study contain about 5.1% of ASCs, the frequency of ASCs in SVF from the hip/thigh region is only 1.2%. Moreover, this 1.2% is the average of a population in which some donors hardly possess any adipose-derived stem cells (see spreading ASC frequency hip/thigh in Fig. 1). Despite this more than four-fold difference, the frequency of ASCs in adipose tissue from the hip/thigh region is still much higher compared with the frequency of MSCs in the bone marrow compartment, which is as low as 0.001%–0.01% (Pittenger et al. 2000), thereby making the hip/thigh region still a much more attractive stem-cell source for tissue engineering therapies.

What are the implications of these stem-cell frequencies for clinical practice? We have shown that 0.5–2.0×108 SVF cells can be harvested from 100 g adipose tissue, an amount that can easily be obtained from a patient (Aust et al. 2004; De Ugarte et al. 2003; Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. 2006; Zuk et al. 2001). With an ASC frequency of 5.1%, the SVF isolates contain between 2.6–10.2×106 stem cells, which is an amount that appears to be sufficient for cell-based therapies as compared with the amount of cells used by others (Erickson et al. 2002; Fan et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2003; Zheng et al. 2006). This implies that time-consuming culturing and expanding steps of the stem cells can be avoided. In comparison, a bone marrow transplant of 100 ml contains approximately 6.0×108 nucleated cells (Zuk et al. 2002), of which only 0.001%–0.01% (0.06–0.006×106 cells) are stem cells (Pittenger et al. 2000).

To determine the frequency of CFU capable of differentiating into the osteogenic lineage, a CFU-ALP assay has been performed on cells from the abdomen and hip/thigh region. The frequencies of CFU-ALP ( ± 3%) are almost comparable with those of the CFU-F (Figs. 1b, 2). This is higher than the value that Mitchell et al. (2006) have found in their clonogenic assay of freshly isolated stromal cells (±0.5%). However, they have used a different assay method and shorter incubation period, and their frequency increases to the same level (5%) after progressive passaging (Mitchell et al. 2006).

SVF cells have been cultured up to passage 3 to obtain a homogeneous population of ASCs as starting material for differentiation studies toward the chondrogenic lineage. When comparing the growth kinetics of these cultured ASCs from the abdomen and hip/thigh region, the cell doubling time appears to be similar, being approximately 2 days. This is in accordance with the findings of others who have compared the replication rate of adipocyte precursor cells from various tissue-harvesting sites (Hauner et al. 1988; Pettersson et al. 1985; Roncari et al. 1981; Zuk et al. 2001). On the other hand, when comparing SVF cells from omental and subcutaneous fat, van Harmelen et al. (2004) have found a difference in cell proliferation rate; however, this may be explained by differences in methodological approach, since they use stromal cells instead of cultured ASCs. As we have shown that different fat depots contain different numbers of stem cells, these differences in proliferation rate may be caused by differences in initial stem-cell numbers when using SVF cells. This is reflected in the finding that, in our study, SVF cells derived from abdominal fat reach 80%–90% confluency within 5 days, whereas SVF cells derived from adipose tissue of the hip/thigh region take more than 9 days to reach 80%–90% confluency when seeded in the same density (data not shown).

In addition to the determination of growth kinetics, we have phenotypically characterized the cultured ASCs. The surface-marker expression profile is in accordance with those found by others (Mitchell et al. 2006; Schaffler and Buchler 2007; Varma et al. 2007), making both tissue sites fully comparable with each other (Tables 1, 3).

The homogeneous ASC population has been induced to the osteogenic and chondrogenic lineages. Having determined the osteogenic differentiation capacity of ASCs, we have shown significant up-regulation of osteogenic gene expression, ALP activity, and matrix mineralization. Interestingly, although no significant difference has been detected in ALP activity between ASCs from the abdomen and hip/thigh regions, ASCs from the hip/thigh region tend to show higher values of ALP activity after induction. This might be related to the underlying bone tissue, thereby implying that the ASCs of the hip/thigh region are less multipotent and more committed to the osteogenic lineage.

The chondrogenic differentiation capacity of the ASCs has been demonstrated by the up-regulation of AGG and COL10α1 gene expression and the production of matrix proteins. No difference has been detected in the chondrogenic differentiation potential between ASCs from the abdomen and hip/thigh regions. However, in the PCR studies, we have not succeeded in quantifying COL2α and Col2B mRNA expression for any of the donors tested. Others have obviously faced the same difficulty when trying to measure the up-regulation of COL2B genes in MSCs (Huang et al. 2004; Winter et al. 2003; Zuk et al. 2002). Although intending to measure collagen Type X mRNA expression as a hypertrophic and therefore late marker of chondrogenesis, we have noticed that this mRNA is expressed earlier than collagen Type II mRNA. This is surprising, as we would expect stem cells to have to differentiate into chondrocytes before they can become hypertrophic. However, this unexpected hierarchy of chondrogenic gene expression has also been found by Mwale et al. (2006). Moreover, both Mwale et al. (2006) and we have found AGG to be constitutively expressed in MSCs. Because of this constitutive expression of AGG and the early up-regulation of COL10α1, Mwale et al. (2006) warn against using these molecules as markers for chondrogenesis and chondrocytic hypertrophy. We think that these genes can nevertheless be used as markers for differentiation into the chondrogenic lineage, albeit being exclusively shown as the quantitative up-regulation of gene expression, and always in combination with other chondrogenic markers (an awareness of the possible difference in the function of COL10α1 in chondrogenesis in adult stem cells when compared with embryonic stem cells is also necessary).

Our lack of detection of any significant differences in the osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation potential when comparing ASCs from the two tissue-harvesting sites seems to be in contrast with studies of Hauner and Entenmann 1991) who have found differences in the adipogenic differentiation potential between SVF cells from abdominal and femoral adipose tissue. However, since Hauner and Entenmann 1991) have used fresh SVF cells instead of culture-passaged ASCs, the variation in differentiation potential might be attributable to differences in numbers of ASCs in the SVF isolates of the two regions, as we have shown in this study. Other factors responsible for the variation in differentiation potential can be ascribed to other specific histological characteristics of the adipose tissue at the anatomical site, such as vascularity and amount of fibrous tissue (Lennon et al. 2000; Peptan et al. 2006; Pittenger et al. 2000), and to differences in the regulation of gene expression (Djian et al. 1983; Peptan et al. 2006; Pittenger et al. 2000).

We therefore conclude that the yield of ASCs is dependent on the tissue-harvesting site. In planning the optimal one-stage procedure for the regeneration of cartilage tissue, factors that can positively influence the outcome of the operation must be taken into account. In view of this, the abdomen seems to be preferable to the hip/thigh region for harvesting ASCs.

References

Asakura A, Komaki M, Rudnicki M (2001) Muscle satellite cells are multipotential stem cells that exhibit myogenic, osteogenic, and adipogenic differentiation. Differentiation 68:245–253

Aust L, Devlin B, Foster SJ, Halvorsen YD, Hicok K, Laney T du, Sen A, Willingmyre GD, Gimble JM (2004) Yield of human adipose-derived adult stem cells from liposuction aspirates. Cytotherapy 6:7–14

Barry FP (2003) Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in joint disease. Novartis Found Symp 249:86–96

De Ugarte DA, Morizono K, Elbarbary A, Alfonso Z, Zuk PA, Zhu M, Dragoo JL, Ashjian P, Thomas B, Benhaim P, Chen I, Fraser J, Hedrick MH (2003) Comparison of multi-lineage cells from human adipose tissue and bone marrow. Cells Tissues Organs 174:101–109

Djian P, Roncari AK, Hollenberg CH (1983) Influence of anatomic site and age on the replication and differentiation of rat adipocyte precursors in culture. J Clin Invest 72:1200–1208

Dresser R (2001) Ethical issues in embryonic stem cell research. JAMA 285:1439–1440

Erickson GR, Gimble JM, Franklin DM, Rice HE, Awad H, Guilak F (2002) Chondrogenic potential of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 290:763–769

Fan H, Hu Y, Zhang C, Li X, Lv R, Qin L, Zhu R (2006) Cartilage regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and a PLGA-gelatin/chondroitin/hyaluronate hybrid scaffold. Biomaterials 27:4573–4580

Gronthos S, Zannettino AC, Hay SJ, Shi S, Graves SE, Kortesidis A, Simmons PJ (2003) Molecular and cellular characterisation of highly purified stromal stem cells derived from human bone marrow. J Cell Sci 116:1827–1835

Guilak F, Awad HA, Fermor B, Leddy HA, Gimble JM (2004) Adipose-derived adult stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering. Biorheology 41:389–399

Halvorsen YD, Franklin D, Bond AL, Hitt DC, Auchter C, Boskey AL, Paschalis EP, Wilkison WO, Gimble JM (2001) Extracellular matrix mineralization and osteoblast gene expression by human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. Tissue Eng 7:729–741

Harmelen V van, Skurk T, Rohrig K, Lee YM, Halbleib M, Aprath-Husmann I, Hauner H (2003) Effect of BMI and age on adipose tissue cellularity and differentiation capacity in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27:889–895

Harmelen V van, Rohrig K, Hauner H (2004) Comparison of proliferation and differentiation capacity of human adipocyte precursor cells from the omental and subcutaneous adipose tissue depot of obese subjects. Metabolism 53:632–637

Hattori H, Sato M, Masuoka K, Ishihara M, Kikuchi T, Matsui T, Takase B, Ishizuka T, Kikuchi M, Fujikawa K, Ishihara M (2004) Osteogenic potential of human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells as an alternative stem cell source. Cells Tissues Organs 178:2–12

Hauner H, Entenmann G (1991) Regional variation of adipose differentiation in cultured stromal-vascular cells from the abdominal and femoral adipose tissue of obese women. Int J Obes 15:121–126

Hauner H, Wabitsch M, Pfeiffer EF (1988) Differentiation of adipocyte precursor cells from obese and nonobese adult women and from different adipose tissue sites. Horm Metab Res Suppl 19:35–39

Helder MN, Knippenberg M, Klein-Nulend J, Wuisman PI (2007) Stem cells from adipose tissue allow challenging new concepts for regenerative medicine. Tissue Eng 8:1799–1808

Huang JI, Zuk PA, Jones NF, Zhu M, Lorenz HP, Hedrick MH, Benhaim P (2004) Chondrogenic potential of multipotential cells from human adipose tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg 113:585–594

Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE, Caplan AI, Bruder SP (1997) Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J Cell Biochem 64:295–312

Lacasa D, Garcia E, Henriot D, Agli B, Giudicelli Y (1997) Site-related specificities of the control by androgenic status of adipogenesis and mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade/c-fos signaling pathways in rat preadipocytes. Endocrinology 138:3181–3186

Lennon DP, Haynesworth SE, Arm DM, Baber MA, Caplan AI (2000) Dilution of human mesenchymal stem cells with dermal fibroblasts and the effects on in vitro and in vivo osteochondrogenesis. Dev Dyn 219:50–62

Lowry OH (1955) Micromethods for the assay of enzyme. II Specific procedure. Alkaline phosphatase. Methods Enzymol 4:371–372

Masuzaki H, Ogawa Y, Isse N, Satoh N, Okazaki T, Shigemoto M, Mori K, Tamura N, Hosoda K, Yoshimasa Y (1995) Human obese gene expression. Adipocyte-specific expression and regional differences in the adipose tissue. Diabetes 44:855–858

Mitchell JB, McIntosh K, Zvonic S, Garrett S, Floyd ZE, Kloster A, Di Halvorsen Y, Storms RW, Goh B, Kilroy G, Wu X, Gimble JM (2006) Immunophenotype of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes in stromal-associated and stem cell-associated markers. Stem Cells 24:376–385

Monjo M, Rodriguez AM, Palou A, Roca P (2003) Direct effects of testosterone, 17 beta-estradiol, and progesterone on adrenergic regulation in cultured brown adipocytes: potential mechanism for gender-dependent thermogenesis. Endocrinology 144:4923–4930

Murphy JM, Dixon K, Beck S, Fabian D, Feldman A, Barry F (2002) Reduced chondrogenic and adipogenic activity of mesenchymal stem cells from patients with advanced osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 46:704–713

Mwale F, Stachura D, Roughley P, Antoniou J (2006) Limitations of using aggrecan and type X collagen as markers of chondrogenesis in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. J Orthop Res 24:1791–1798

Nakahara H, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI (1991) Culture-expanded human periosteal-derived cells exhibit osteochondral potential in vivo. J Orthop Res 9:465–476

Oedayrajsingh-Varma MJ, Ham SM van, Knippenberg M, Helder MN, Klein-Nulend J, Schouten TE, Ritt MJ, Milligen FJ van (2006) Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell yield and growth characteristics are affected by the tissue-harvesting procedure. Cytotherapy 8:166–177

Peptan IA, Hong L, Mao JJ (2006) Comparison of osteogenic potentials of visceral and subcutaneous adipose-derived cells of rabbits. Plast Reconstr Surg 117:1462–1470

Peterson B, Zhang J, Iglesias R, Kabo M, Hedrick M, Benhaim P, Lieberman JR (2005) Healing of critically sized femoral defects, using genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue. Tissue Eng 11:120–129

Pettersson P, Van R, Karlsson M, Bjorntorp P (1985) Adipocyte precursor cells in obese and nonobese humans. Metabolism 34:808–812

Pittenger MF, Mosca JD, McIntosh KR (2000) Human mesenchymal stem cells: progenitor cells for cartilage, bone, fat and stroma. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 251:3–11

Planat-Benard V, Silvestre JS, Cousin B, Andre M, Nibbelink M, Tamarat R, Clergue M, Manneville C, Saillan-Barreau C, Duriez M, Tedgui A, Levy B, Penicaud L, Casteilla L (2004) Plasticity of human adipose lineage cells toward endothelial cells: physiological and therapeutic perspectives. Circulation 109:656–663

Prunet-Marcassus B, Cousin B, Caton D, Andre M, Penicaud L, Casteilla L (2005) From heterogeneity to plasticity in adipose tissues: site-specific differences. Exp Cell Res 312:727–736

Ramsay TG, White ME, Wolverton CK (1995) The onset of maternal diabetes in swine induces alterations in the development of the fetal preadipocyte. J Anim Sci 73:69–76

Rangappa S, Fen C, Lee EH, Bongso A, Sim EK (2003) Transformation of adult mesenchymal stem cells isolated from the fatty tissue into cardiomyocytes. Ann Thorac Surg 75:775–779

Rodriguez-Cuenca S, Monjo M, Proenza AM, Roca P (2005) Depot differences in steroid receptor expression in adipose tissue: possible role of the local steroid milieu. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288:E200–E207

Roncari DA, Lau DC, Kindler S (1981) Exaggerated replication in culture of adipocyte precursors from massively obese persons. Metabolism 30:425–427

Schaffler A, Buchler C (2007) Concise review: adipose tissue-derived stromal cells-basic and clinical implications for novel cell-based therapies. Stem Cells 25:818–827

Varma MJ, Breuls RG, Schouten TE, Jurgens WJ, Bontkes HJ, Schuurhuis GJ, Ham SM van, Milligen FJ van (2007) Phenotypical and functional characterization of freshly isolated adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 16:91–104

Venter M van de, Litthauer D, Oelofsen W (1994) Catecholamine stimulated lipolysis in differentiated human preadipocytes in a serum-free, defined medium. J Cell Biochem 54:1–10

Williams CG, Kim TK, Taboas A, Malik A, Manson P, Elisseeff J (2003) In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a photopolymerizing hydrogel. Tissue Eng 9:679–688

Winter A, Breit S, Parsch D, Benz K, Steck E, Hauner H, Weber RM, Ewerbeck V, Richter W (2003) Cartilage-like gene expression in differentiated human stem cell spheroids: a comparison of bone marrow-derived and adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. Arthritis Rheum 48:418–429

Zheng B, Cao B, Li G, Huard J (2006) Mouse adipose-derived stem cells undergo multilineage differentiation in vitro but primarily osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation in vivo. Tissue Eng 12:1891–1901

Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW, Katz AJ, Benhaim P, Lorenz HP, Hedrick MH (2001) Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng 7:211–228

Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, Alfonso ZC, Fraser JK, Benhaim P, Hedrick MH (2002) Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell 13:4279–4295

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Jan van Goyen Clinic for providing adipose tissue, the Department of Physiology for use of their hypoxia workstation, Zufu Lu for his technical assistance with PCR analyses, and Jolanda de Blieck for her assistance in the lab.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jurgens, W.J.F.M., Oedayrajsingh-Varma, M.J., Helder, M.N. et al. Effect of tissue-harvesting site on yield of stem cells derived from adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Cell Tissue Res 332, 415–426 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-007-0555-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-007-0555-7