Abstract

In 2003, a Heat Health Watch Warning System was developed in France to anticipate heat waves that may result in a large excess of mortality. The system was developed on the basis of a retrospective analysis of mortality and meteorological data in fourteen pilot cities. Several meteorological indicators were tested in relation to levels of excess mortality. Computations of sensibility and specificity were used to choose the meteorological indicators and the cut-offs. An indicator that mixes minimum and maximum temperatures was chosen. The cut-offs were set in order to anticipate events resulting in an excess mortality above 100% in the smallest cities and above 50% in Paris, Lyon, Marseille and Lille. The system was extended nationwide using the 98th percentile of the distribution of minimum and maximum temperatures. A national action plan was set up, using this watch warning system. It was activated on 1st June 2004 on a national scale. The system implies a close cooperation between the French Weather Bureau (Météo France), the National Institute of Health Surveillance (InVS) and the Ministry of Health. The system is supported by a panel of preventive actions, to prevent the sanitary impact of heat waves.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Applegate WB, Runyan JW Jr, Brasfield L, Williams ML, Konigsberg C, Fouche C (1981) Analysis of the 1980 heat wave in Memphis. J Am Geriatr Soc 29:337–342

Auger N, Kosatsky T (2002) Chaleur accablante. Mise à jour de la littérature concernant les impacts de santé publique et proposition de mesures d’adaptation. Direction de la santé publique, Montréal, pp 1–34

Basu R, Samet JM (2002) Relation between elevated ambient temperature and mortality: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiol Rev 24:190–202

Benbow N (1997) Chaleur et mortalité à Chicago en juillet 1995. Climat Santé 18:61–70

Besancenot JP (1990a) L’organisme humain face à la chaleur. Sécheresse, Science et changements planétaires 1:98–104

Besancenot JP (1990b) Les fortes chaleurs sont-elles dangereuses? Recherche (la) 223:930–933

Besancenot JP (1997) Les grands paroxysmes climatiques et leurs répercussions sur la santé. Presse Therm Clim 134:237–246

Besancenot JP (2001) Climat et santé. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, pp 1–128

Besancenot JP (2002) Vagues de chaleur et mortalité dans les grandes agglomérations urbaines. Environ Risques Santé 1:229–240

Braga AL, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J (2002) The effect of weather on respiratory and cardiovascular deaths in 12 U.S. cities. Environ Health Perspect 110:859–863

Changnon SA, Kunkel KE, Reinke BC (1996) Impacts and responses to the 1995 heat wave: a call to action. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77:1497–1506

Chestnut L, Breffle WS, Smith J, Kalkstein LS (1998) Analysis of differences in hot-weather-related mortality across 44 U.S. metropolitan areas. Environ Sci Policy 1:59–70

Cooter E (1993) Approche bioclimatique d’une forte vague de chaleur. Le cas de l’Oklahoma. Climat Santé 51–70

Díaz J, García R, Velázquez de Castro F, Hernández E, López C, Otero A (2002a) Effects of extremely hot days on people older than 65 years in Seville (Spain) from 1986 to 1997. Int J Biometeorol 46:145–149

Diaz J, Jordan A, Garcia R, Lopez C, Alberdi JC, Hernandez E, Otero A (2002b) Heat waves in Madrid 1986–1997: effects on the health of the elderly. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 75:163–170

Donaldson GC, Keatinge WR, Nayha S (2003) Changes in summer temperature and heat-related mortality since 1971 in North Carolina, South Finland, and Southeast England. Environ Res 91:1–7

Doucoure D (1993) La relation mortalité-météorologie: détermination d’un seuil critique de température et mise au point d’un système de prévention de la surmortalité estivale. Climat Santé 10:129–135

Hajat S, Kovats RS, Atkinson RW, Haines A (2002) Impact of hot temperatures on death in London: a time series approach. J Epidemiol Community Health 56:367–372

Hémon D, Jougla E (2003) Surmortalité liée à la canicule d’août 2003. Rapport d’étape (1/3). Estimation de la surmortalité et principales caractéristiques épidémiologiques. INSERM. 1–59. 2003. INSERM, Paris

InVS (Institut National de Veille Sanitaire) (2003) Impact sanitaire de la vague de chaleur en France survenue en août 2003. Rapport d’étape, 28 août 2003.http://www.invs.sante.fr. 28-8-2003

Jendritzky G, Bucher K, Laschewski G, Walther H (2000) Atmospheric heat exchange of the human being, bioclimate assessments, mortality and thermal stress. Int J Circumpolar Health 59(3–4):222–227

Jones TS (1993) Retour sur un sujet controversé: morbidité et mortalité durant la vague de chaleur de juillet 1980 au Missouri. Climat Santé 25–49

Jones TS, Liang AP, Kilbourne EM, Griffin MR, Patriarca PA, Wassilak SG, Mullan RJ, Herrick RF, Donnell HD Jr, Choi K, Thacker SB (1982) Morbidity and mortality associated with the July 1980 heat wave in St Louis and Kansas City, Mo. JAMA 247:3327–3331

Kalkstein LS (2002) Description of our heat/health watch-warning systems: their nature and extent, and required resources. Center for Climatic Research and University of Delaware, pp 1–31

Kalkstein LS, Jamason PF, Greene JS, Libby J, Robinson L (1996) The Philadelphia hot weather-health watch/warning system: development and application, summer 1995. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77:1519–1528

Katsouyanni K, Trichopoulos D, Zavitsanos X, Touloumi G (1988) The 1987 Athens heatwave. Lancet 2:573

Kirk ML (1996) Chaleur et mortalité des personnes âgées aux Etats-Unis: approche cartographique. Climat Santé 15:25–41

Kunkel KE, Changnon SA, Reinke BC, Arritt RW (1996) The July 1995 heat wave in the midwest: a climatic perspective and critical waether factors. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77:1507–1518

Kunst AE (1996) Température et mortalité aux Pays-Bas. Essai d’analyse chronologique. Climat Santé 15:43–64

Laaidi K (1997) Les éléments du climat et leurs possibles implications sur la santé. Presse Therm Clim 134:213–223

Laaidi M, Laaidi K, Besancenot JP (2002) La relation température mortalité en France. Les possibles répercussions d’un changement climatique. Actes du Colloque “Regards croisés sur les changements globaux” Inra, Cnes, Cnfcg, Insu. Arles, France, 25–29 novembre 2002

Laaidi K, Laaidi M, Besancenot JP (2003) Temperature related mortality in Paris, France. Br Med J (submitted)

Marmor M (1975) Heat wave mortality in New York City, 1949 to 1970. Arch Environ Health 30:130–136

Michelozzi P, Kirchmayer U, Katsouyanni K, Biggeri A, Bertollini R, Anderson R, Benne B, McGregor G, Kassomenos P (2004) The PHEWE project - Assessment and prevention of acute health effects of assessment and prevention of acute health effects of weather conditions in Europe. Epidemiology 15:102–103

Ministère de la santé et de la protection sociale, Ministère délégué aux personnes âgées (2004) Plan National Canicule, actions nationales et locales à mettre en œuvre par les pouvoirs publics afin de prévenir et réduire les conséquences sanitaires d’’une canicule, http://www.sante.gouv.fr/canicule/doc/plan_canicule.pdf

Robinson PJ (2000) On the definition of a heat wave. J Appl Meteorol 40:762–775

Rogers IR, Williams A (2000) Heat-related illness. In: Cameron P, Jelinek G, Kelly A-M, Murray L, Heyworth J (eds) Textbook of adult emergency medicine. Edinburgh, pp 607–610

Rooney C, McMichael AJ, Kovats RS, Coleman MP (1998) Excess mortality in England and Wales, and in Greater London, during the 1995 heatwave. J Epidemiol Community Health 52:482–486

Sartor F, Snacken R, Demuth C, Walckiers D (1995) Temperature, ambient ozone levels, and mortality during summer 1994, in Belgium. Environ Res 70:105–113

Semenza JC, Rubin CH, Falter KH, Selanikio JD, Flanders WD, Howe HL, Wilhelm JL (1996) Heat-related deaths during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. N Engl J Med 335:84–90

Simonet J (1985) Vague de chaleur de juillet 1983: étude épidémiologique et physiopathologique. 1–161. 1985. Faculté de Médecine, Marseille

Smoyer KE (1998) A comparative analysis of heat waves and associated mortality in St. Louis, Missouri-1980 and 1995. Int J Biometeorol 42:44–50

Thirion X (1992) La vague de chaleur de juillet 1983 à Marseille: enquête sur la mortalité, essai de prévention. Santé Publique 4:58–64

WHO Regional Committee for Europe (2003) Heatwaves: impacts and responses. WHO 1–11

Acknowledgements

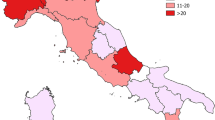

The authors are grateful to the National Institute of Statistic and Economic Studies (INSEE) for the mortality data, to A. Maulpoix and P. De Crouy-Chanel who produced the maps, to E. Bertrand and S. Guitton who helped with the bibliographic research, to all the participants who collected the sanitary indicators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Modifications of the system for summer 2005

Modifications of the system for summer 2005

The experience of the first year of running of the system has lead to several changes in its design. Among these adjustments, the definition of the warning thresholds for the biometeorological indicators was slightly modified. Other modifications were done regarding the practical organisation of the system and especially the management of situations at-risk.

In 2005, the thresholds have been re-defined for two reasons. First, the use of the 98th percentile of temperature was not consistent with the use of a temperature averaged over three days. The thresholds have to be based on the distribution of moving average of temperature over three days. Second, it was assumed that the method used to define the thresholds was not applicable unless specific conditions were met. These conditions are a sufficient number of heat waves (>5) and a baseline of mortality stable enough (i.e. main cities only). Pilot cities that did not meet these criteria were then excluded from the study: Bordeaux, Toulouse and Nice because they had too few heat waves; Grenoble, Lille, Limoges, Dijon because the mortality baseline was too noisy (here the choice was qualitative). Using the remaining cities, new percentiles, based on the distribution of the averaged temperatures were computed and tested. The 99.5th percentile was chosen for its optimal combining of sensitivity and specificity. Yet, it has to be underlined that these notions of sensitivity and specificity are not readily applicable to this topic, since heat waves are not reproducible events. They only give indications on the capability of the thresholds, but the final choice is mainly subjective.

Using the 99.5th percentile new thresholds were proposed, as shown in Table 1. In most cities, the difference with the previous thresholds is lower than 1°C, expect in Lille, Grenoble and Limoges where the minimal threshold was substantially raised, and in Toulouse where the maximal threshold was lowered.

The system is still imperfect, as the temperatures are not the only factors to consider regarding heat load. The humidity may also be interesting, but cannot be used in a predictive system due to the difficulties of forecasting. The characteristic of the summer before the heat wave may also be of importance. Indeed, the dramatic impact of the 2003 heat wave may partly be explained by a very warm summer, with elevated temperatures in June and July, which created a state of exhaustion in the most vulnerable groups of population. In addition, the forecasting of meteorological parameters is always associated with an uncertainty that has to be dealt with. For instance, it was observed in 2004 that the maximal temperatures were slightly underestimated, while the minimal temperatures were overestimated. These errors were small and infrequent (<1°C for 76% of the days) but still interfered with the specificity of the system. Indeed, situations when the indicators are close to the thresholds are usual and highly sensitive to even minor uncertainties in the forecasting. This led to the definition of additional qualitative criteria to consider: humidity, wind, air pollution, intensity and duration of the heat wave, sanitary signals. For borderline situations, the additional information is discussed with the health scientists and with the meteorologists. It is believed that this will help in improving the communicability and the efficiency of the system, which were the main concerns for the users of this system.

Cities | 2004 | 2005 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Threshold minimal | Threshold maximal | Threshold minimal | Threshold maximal | |

Bordeaux | 22 | 36 | 21 | 35 |

Dijon | 19 | 34 | 19 | 34 |

Grenoble | 15 | 35 | 19 | 34 |

Lille | 15 | 32 | 18 | 31 |

Limoges | 16 | 36 | 20 | 33 |

Lyon | 20 | 34 | 20 | 34 |

Marseille | 22 | 34 | 22 | 34 |

Nantes | 20 | 33 | 20 | 34 |

Nice | 24 | 30 | 24 | 31 |

Paris | 21 | 31 | 21 | 31 |

Strasbourg | 17 | 35 | 19 | 34 |

Toulouse | 21 | 38 | 21 | 36 |

Tours | 17 | 34 | 19 | 35 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pascal, M., Laaidi, K., Ledrans, M. et al. France’s heat health watch warning system. Int J Biometeorol 50, 144–153 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-005-0003-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-005-0003-x