Abstract

Purpose

The transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) technique uses a preperitoneal mesh preformed with a permanent memory ring, which greatly facilitates application of Rives’ technique. The purpose of this retrospective study was to evaluate our primary results by systematic clinical and ultrasound evaluations more than 1 year after surgery.

Methods

This unicentric study included all consecutive adult patients treated with surgery for a groin hernia by the same surgeon using the same technique between December 2006 and December 2008. Any patient who participated in this study had both a systematic clinical and ultrasound control between 6 months and 3 years after surgery.

Results

In this study, we performed 145 hernia repairs. There was no infection of the mesh and no clinical recurrence; additionally there was an ultrasound recurrence (n = 3) in 2% of asymptomatic patients and chronic pain in 4.8% of patients who did not require the consumption of systematic painkillers and are not limited in their activities.

Conclusions

It is feasible to correct a groin hernia using a preperitoneal preformed mesh with a permanent memory ring. Our study confirms the positive results of Pélissier and colleagues (Pélissier and Ngo, Ann Chir 131:590–594, 2006; Pélissier et al. J Chir 144(4):5S35–5S40, 2007; Pélissier et al. Hernia 11:229–234, 2007; Pélissier et al. Hernia 12:51–56, 2007) and Berrevoet et al. (Hernia 13:243–249, 2009; Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 395:557–562, 2010) and is the first study to use a systematic clinical and ultrasound control more than 1 year after surgery. This technique has a low rate of complications, including ultrasound recurrence in 2% of patients without any clinical recurrence and chronic pain in 4.8% of patients who did not require the consumption of systematic painkillers and are not limited in their activities. This technique consisted of the placement of a patch in the preperitoneal space, which combines the benefits of the anterior approach (i.e., easy technique, short learning curve, low cost) and the preperitoneal placement of the mesh (less recurrence, less pain). This procedure is a good alternative to Lichtenstein’s technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Groin hernia repair is a very frequent procedure in general surgery. Although many different techniques have been described, nowadays there is still no consensus as to the best technique. However, the evidence indicates that there is a lower rate of recurrence using mesh [1]. Unsolved questions still remain as to where to place the mesh and with which technique.

In the first instance, we prefer the use of the anterior method to the laparoscopic approach because it is feasible under spinal anesthesia and there are no major complications such as gas embolism or visceral and arterial injuries, although these kinds of complications are rare. Moreover, laparoscopic techniques have a steeper learning curve with a similar recurrence rate [2] and higher cost.

Many techniques involving mesh use an anterior approach. Lichtenstein’s technique [3] is probably the most frequently used anterior technique. Other techniques that place the mesh in the preperitoneal space have been described by Stoppa [4], Rives [5] and Alexandre [6]. More recently, other techniques have been developed by Kugel and involve placement of the mesh in the preperitoneal space [7]. These techniques have the advantage of using the intra-abdominal pressure to apply the mesh behind the area of weakness in the groin, thereby covering direct, indirect and femoral defects. Rives’ technique has some disadvantages such as the need to widely open the transversalis fascia for correct positioning of the mesh, which can shrink, and requires a large number of fixation stitches especially on Cooper’s ligament. These stitches can cause difficult in controlling bleeding, and a hematoma can potentially come into contact with the prosthesis.

The transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) technique uses a preperitoneal mesh preformed with a permanent memory ring, which greatly facilitates application of Rives’ technique. This new technique is now possible since the marketing by Bard of its Polysoft® mesh. The permanent memory ring allows optimal deployment to avoid shrinking of the mesh. Moreover, there is no need to use fixation stitches; the mesh can be attached by superficially closing the transversalis fascia. Studies by Pélissier and colleagues and, more recently, Berrevoet and colleagues have evaluated the preliminary results obtained with this new kind of mesh [8, 9], and they look promising. However, systematic postoperative clinical and ultrasound evaluations are far from being fully studied. Moreover, it is difficult to evaluate whether a technique described only by two separate teams of experts will yield the same excellent results in a general hospital setting.

Objectives: the end-points

The purpose of this retrospective study was to evaluate our primary results in terms of recurrence, postoperative pain and other complications by systematic clinical and ultrasound evaluations more than 1 year after surgery. Our secondary aim was to evaluate the time of recovery and the time to return to work. This study was presented to the ethics committee of our hospital and has received their support. Every patient was informed orally, received an information sheet, and signed an informed consent form.

Patients and methods

Patients

This unicentric study included all consecutive adult patients treated with surgery for a groin hernia by the same surgeon using the same technique between December 2006 and December 2008. Bilaterals hernias, recurrences and patients with an antecedent of pelvic surgery were included. Emergency procedures were also included. No exclusions were made based on anesthetic status. We included ASA IV patients and patients with a contraindication for general anesthesia. The only exclusion criterion was the contraindication for the use of a mesh, such as in pediatric patients or patients who required an intestinal resection for an incarcerated hernia. In such cases, Shouldice’s procedure was performed.

Surgical technique

We performed the same technique described previously by the groups of Pélissier and Berrevoet [8, 9]. When there was no contraindication, the operation was performed under spinal anesthesia unless the patient specifically requested general anesthesia. Although the TIPP technique was first described under local anesthesia [8], we did not use it.

Briefly, we performed a 2- to 5-cm incision depending on the patient’s stoutness. The incision was made in a horizontal skinfold starting half way across the line between the superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. We have confirmed that this incision always provides the best access to the internal ring [9]. Scarpa’s fascia and the external oblique aponeurosis were opened classically without any extended dissection. First, we located the cord and checked for indirect and direct hernia. The inguinal nerves were not routinely identified, but if the ilioinguinal nerve is found, it will always be saved and gently placed internally behind the retractor. In cases of indirect hernia, the sac was separated from the cord by a bloodless dissection using peanut gauze up to the internal ring. In cases of direct hernia, we checked routinely for an associated indirect hernia.

In cases of indirect hernia, the internal ring was dilated and offered easy access to the preperitoneal space where the epigastric vessels can be found medially. These vessels were retracted medially and gauze was introduced into the preperitoneal space. For a direct hernia, the preperitoneal space was dissected through the dilated fascia transversalis. We generally began gauze dissection above the pubis tubercle and pushed the peritoneum up and medially. For good positioning of the mesh, the dissection must be performed until Cooper’s ligament and the pubis bone can be palpated. At this time, an eventual undiagnosed femoral hernia can be identified and treated using the same procedure. Dissection of the sac and cord must be performed up to the point where the spermatic cord and spermatic vessels separate, so that the cord can be easily parietalized. We believe that if the dissection is wide enough laterally, the mesh does not need to be split, which avoids cord strangulation and postoperative orchitis. In our study, we never split the Polysoft® mesh laterally to create a new internal orifice. If the peritoneum is accidentally opened, we suggest that is not closed immediately but that the dissection is continued until enough preperitoneal space is obtained, and then the peritoneum can be closed or resected if necessary. Closing the peritoneum at the end of the dissection can facilitate dissection by intra-abdominal palpation of the sac. If the sac was resected, it was closed under visual control using an absorbable stitch. The lateral digital dissection required to create the appropriate space for the mesh can be a little bit more difficult, especially in the case of a prior McBurney operation or a sliding hernia containing a big sigmoid. Prior pelvic surgery or pelvic irradiation is not considered a contraindication of the technique.

Placement of the mesh is facilitated by the memory ring of the Polysoft® patch. It is first placed medially behind Cooper’s ligament and then laterally to the internal ring. The prosthesis must not be pushed too medially, where there is often more space due to an easier dissection due to insufficient lateral overlap, and an early recurrence could occur. A larger patch might avoid this technical problem.

To check good positioning of the mesh, we asked the patient to cough. We did not stitch the prosthesis laterally but just used a few stitches to tie the fascia transversalis or the dilated ring to the mesh to avoid any migration. We then recreated an internal orifice by attaching the cremaster muscle to the inguinal ligament by two absorbable stitches.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered as a single shot before the procedure. Usually, we did not leave a drainage tube. We estimate the duration of this surgery to be similar to that required for Lichtenstein’s procedure.

Evaluation

All patients participating in this study had a systematic clinical and ultrasound control between 6 months and 3 years after surgery (average 21 months).

During the clinical evaluation, we collected information on the time of recovery, time to return to work, the use of painkillers and possible complications within 24 h, 1 month and more than 1 year after surgery.

We did not use the visual analog pain scale for pain evaluation because postoperative pain is extremely variable over time, and we think that the use of painkillers after surgery is a better proxy for pain evaluation.

The ultrasound control was performed by two independent radiologists. They checked the inguinal repair first while lying down, then standing up, and finally during Valsalva’s procedure. This independent ultrasound control performed by two experienced radiologists is the only objective control of the absence of recurrence and the correct positioning and deployment of the mesh more than 6 months after surgery.

Results

Patients

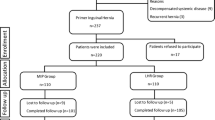

Over the 2-year study period, 141 patients were included. Five died before the clinical examination and were excluded. The deaths occurred between 5 and 11 months after surgery and had no link to the hernia pathology. This high death rate is probably due to the fact that we did not exclude any patients with a symptomatic hernia even if they were very old and ill (i.e., ASA IV patients). Among the 136 remaining patients, 124 (91%) participated in the study. Four (3%) patients were lost to follow-up and seven (5%) did not want to participate. One patient could not be clinically evaluated for medical reasons that had no link to the hernia pathology (Table 1).

The sex ratio was 114 males to 10 females. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.6 kg/m2 with a mean height of 173 cm and weight of 76 kg. The mean age was 54 years (Table 2).

Surgery

Most of the procedures were performed under spinal anesthesia (n = 87, 70%) (Table 3). In our study, we performed 145 hernia repairs on 124 patients. There were 46 repairs on the left side (37%), 57 on the right side (46%) and 21 patients (17%) underwent bilateral repair (Table 4).

Of all the hernia operations, 48% were on indirect hernias and 41% were on direct hernias. Only a few (three) patients had a recurrent hernia (Table 5). An emergency procedure was performed on two patients. The mesh is available in two different sizes: medium (14 cm × 7.5 cm) and large (16 cm × 9.5 cm). We used only a few (15) large meshes, with most (130) procedures using medium mesh.

Hospital stay

When there was no contraindication, we encouraged ambulatory surgery. Leaving the hospital on the day of the surgery was possible for 72 patients (58%). Among the 47 patients who spent one night in the hospital, 22 stayed because of a late operating time, and 11 stayed because of personal preference. Only five patients, including the two emergency procedures, stayed two nights (Table 6; Fig. 1). Most patients (15/21; 71%) that underwent a bilateral procedure stayed only one night.

Postoperative complications

The day after surgery, 83 of 124 (67%) patients showed no complications. With regard to pain, 30 patients experienced pain within the first 24 h after the procedure. There were only a few (11 of 145) minor complications, including four cases of hematoma, six cases of urinary retention, and one case of postoperative nausea.

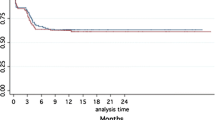

One month after surgery, 109 of 124 (88%) patients had no complications. Eleven patients still reported a low level of pain. There were four cases of minor complications (two hematomas and two seromas). After 1 year, 117 of 124 (94%) patients had no complications, and only 7 of 145 (4.8%) still experienced some pain (Fig. 2).

Painkiller consumption

With regard to the use of painkillers, 18 of 124 (15%) patients took no medication, and 100 of 124 (80%) patients did not take painkillers for more than 1 week (paracetamol only). Only seven patients who had some chronic pain took analgesic drugs for more than 2 weeks. Figure 3 illustrates the duration of oral painkiller consumption after the perioperative intravenous analgesia.

Time to recovery

The average time to recovery was 15 days. The return to work time was 2.6 weeks for office work (n = 35) and 5.6 weeks for manual labor (n = 34). It was inestimable for 55 patients (no work, retired, out of work for other medical reasons).

General outcomes

There were no cases of infection of the mesh, six hematomas (4%), two seromas (1.3%), no clinical recurrence and 2% ultrasound recurrence (n = 3) in asymptomatic patients. In 4.8% (7 of 145) of patients, a low level of pain that did not require the systematic use of analgesics and did not limit patient activities was still present more than a year after surgery and was considered to be chronic pain. No second procedure was needed. The rate of satisfaction more than 1 year after the surgery was 97%. All but three patients stated they would be operated on using the same technique if necessary. There was no vascular (specifically, epigastric vessel) injury.

Discussion

Many techniques are available for groin hernia repair. The evaluation of each of these techniques must include both minor and major complications including recurrence and postoperative pain.

Currently, the choice of a laparoscopic or open approach is still debated. These two approaches have proved similar in terms of recurrence [10–12]. The laparoscopic approach has some disadvantages, including a steep learning curve, higher cost, longer operating times. and higher rates of complication (mainly viscera injury), as well as requiring special equipment, training and technical skills [12]. For these reasons, we prefer to use an anterior approach in the first instance. With anterior approaches, the recurrence rate is lower when a mesh is used [1, 13].

Currently, the most frequent anterior approach for groin hernia repair is probably Lichtenstein’s technique. Many studies have determined that this technique has a recurrence rate of approximately 3% [1, 2, 14]. Preperitoneal placement of the prosthesis has a higher recurrence rate when inexperienced hands use the Stoppa or Rives’ technique [2, 15]. This rate is lower with the TIPP technique, which makes this technique an acceptable alternative to Lichtenstein’s technique.

The TIPP technique is a good technique that has been studied intensively by Pélissier and colleagues [8, 16–18]. They described a recurrence rate between 1 and 2% and a rate of chronic pain of between 5 and 7%. More recently, Berrevoet and his team [9, 19] came to almost the same conclusions, with a recurrence rate of between 1 and 3% and a visual analog pain scale of 0.2 1 year after surgery.

Unfortunately, studies on the systematic clinical and ultrasound controls are far from complete. Moreover, we do not know if such results are reproducible in a general hospital with everyday activity, or if this technique requires the specialised expertise of a university center.

In the present study, we confirm the results of Pelissier and Berrevoet. For the first time, we systematically evaluated all patients who participated using both clinical and independent ultrasound controls. Our study had a participation rate of 91% and included 145 procedures on 124 patients; we found no clinical recurrence and only three ultrasound recurrences (2%) in asymptomatic patients.

The second major complication of groin hernia repair is postoperative pain. Evaluating pain is very difficult. There are a few tools that can help evaluate the feeling of pain at a precise instant, but none of them can help us estimate the pain felt by a patient over a long period. Reviewing the literature [1, 2, 14], we found that the rate of postoperative pain 1 year after Lichtenstein’s procedure ranges from 6% to almost 20%. Our evaluation of postoperative pain revealed that 4.8% of patients still experienced some pain more than 1 year after surgery, but this pain did not require systematic analgesic consumption and did not limit patient activities.

The TIPP technique is an anterior technique involving preperitoneal placement of the mesh, and has the following advantages.

-

1.

The low recurrence rate is not surprising for several reasons. First, there is no shrinking of the mesh even in the long term thanks to the permanent memory ring. This fact was confirmed by the ultrasound control more than 6 months after surgery. Secondly, the mesh covers the three weak points of the groin: direct, indirect and femoral areas. In a study of patients with femoral hernia, 50% had an associated inguinal hernia that was undiagnosed before surgery [20]. Moreover, 9% of recurrences following Lichtenstein’s procedure are femoral hernias, and half of patients with a femoral hernia have an antecedent of inguinal hernia repair [20]. In our study, three patients with an inguinal hernia had also a femoral hernia that was diagnosed perioperatively and treated by the same procedure. Covering the femoral orifice will prevent the occurrence of a femoral hernia, which could be misdiagnosed as an inguinal recurrence.

-

2.

We explain the low rate of postoperative pain with three facts. First, there is minimal dissection around the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves and around the cord [18]. Second, there is no fibrosis of the mesh in contact with the inguinal nerves [16]. Third, there are no fixation stitches, particularly on Cooper’s ligament, that could be painful and possibly cause bleeding with periprosthesis hematoma and postoperative pain.

-

3.

The anterior approach is well known by general surgeons. This technique is easy to learn and to teach, and there is still the possibility to switch to another anterior technique such as Shouldice or Lichtenstein should there be any trouble. These results have been obtained since we began using the Polysoft® mesh. Therefore, in contrast to laparoscopic techniques, there is no major learning curve. In our study, we did not injure the epigastric vessels. An anterior approach is feasible under spinal or even local anesthesia.

A light mesh could further reduce pain and the feeling of a foreign body, but may lead to more recurrences. The use of a permanent memory ring prevents any shrinking of the mesh even in the long term after surgery, as verified by ultrasonic evaluation.

Based on the results from this study and two others, the TIPP procedure for inguinal hernia repair is safe, reproducible and has a low complication rate in terms of recurrence and postoperative pain. This technique allows for the correction of all types of groin hernias with a unique procedure in all types of patients, as it is achievable under spinal or even local anesthesia in all types of surgery hospitals.

Unfortunately, these results are not supported statistically because they were not obtained from a prospective, double blind randomized study. However, the results from this retrospective study based on clinical and ultrasonic reevaluation more than 1 year after the surgery show the feasibility of this technique with its low complication rate and easier learning curve.

We await the results of the TULIP study by Koning, which will compare the TIPP technique to Lichtenstein’s technique using a double blind randomized study [21].

Conclusions

It is feasible to correct a groin hernia using a preperitoneal preformed mesh with a permanent memory ring. Our study—the first to use systematic clinical and ultrasound controls more than 1 year after surgery—confirms the positive results seen by Pélissier [8, 16–18] and Berrevoet [9, 19]. This technique has a low complication rate with no clinical recurrence, 2% ultrasound recurrence in asymptomatic patients, and chronic pain in 4.8% of patients that did not require analgesic consumption and did not limit patient activities.

This technique combines the benefits of an anterior approach and preperitoneal placement of the mesh. Preperitoneal placement of the patch offers two benefits. First, the patch is applied to the abdominal wall by intra-abdominal pressure and reinforces all the weak points of the groin, explaining the low recurrence rate. Second, the mesh is not in contact with the inguinal nerves thus preventing fibrosis in nerve contacts [19]. This fact, together with the limited number of fixation stitches and the limited dissection around the inguinal nerves and the cord, can explain the low rate of postoperative pain and the decreased use of painkillers.

In terms of recurrence and postoperative pain, we conclude that TIPP is a good alternative to Lichtenstein’s technique, which is the most frequently used anterior procedure.

References

McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, Ross S, Grant AM (2003) Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (online) CD001785

Muldoon RL, Marchant K, Johnson DD, Yoder GG, Read RC, Hauer-Jensen M (2004) Lichtenstein vs. anterior preperitoneal prosthetic mesh placement in open inguinal hernia repair: a prospective, randomized trial. Hernia 8:98–103

Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG (1986) Ambulatory outpatient hernia surgery. Including a new concept, introducing tension-free repair. Int Surg 71:1–4

Stoppa R, Petit J, Abourachid H, Henry X, Duclaye C, Monchaux G, Hillebrant JP (1973) Original procedure of groin hernia repair: interposition without fixation of Dacron tulle prosthesis by subperitoneal median approach (in French). Chirurgie 99:119–123

Rives J, Lardennois B, Flament JB, Convers G (1973) The Dacron mesh sheet, treatment of choice of inguinal hernias in adults. Apropos of 183 cases (in French). Chirurgie 99:564–575

Alexandre JH, Dupin P, Levard H, Billebaud T (1984) Treatment of inguinal hernia with unsplit mersylene prosthesis. Significance of the parietalization of the spermatic cord and the ligation of epigastric vessels (in French). Presse Med 13:161–163

Kugel RD (1999) Minimally invasive, nonlaparoscopic, preperitoneal, and sutureless, inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg 178:298–302

Pélissier EP, Blum D, Ngo P, Monek O (2008) Transinguinal preperitoneal repair with the Polysoft patch: prospective evaluation of recurrence and chronic pain. Hernia 12:51–56

Berrevoet F, Maes L, Reyntjens K, Rogiers X, Troisi R, de Hemptinne B (2010) Transinguinal preperitoneal memory ring patch versus Lichtenstein repair for unilateral inguinal hernias. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395:557–562

Hallén M, Bergenfelz A, Westerdahl J (2008) Laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair versus open mesh repair: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 143:313–317

O’Dwyer PJ (2004) Current status of the debate on laparoscopic hernia repair. Br Med Bull 70:105–118

Pavlidis TE (2010) Current opinion on laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc 24:974–976

Amato B, Moja L, Panico S, Persico G, Rispoli C, Rocco N, Moschetti I (2009) Shouldice technique versus other open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (online) CD001543

Champault G, Bernard C, Rizk N, Polliand C (2007) Inguinal hernia repair: the choice of prosthesis outweighs that of technique. Hernia 11:125–128

Veenendaal LM, de Borst GJ, Davids PHP, Clevers GJ (2004) Preperitoneal gridiron hernia repair for inguinal hernia: single-center experience with 2 years of follow-up. Hernia 8:350–353

Pélissier E, Ngo P (2006) Subperitoneal inguinal hernioplasty by anterior approach, using a memory-ring patch. Preliminary results. Ann Chir 131:590–594

Pélissier E, Fingerhut A, Ngo P (2007) Inguinal hernia. What techniques are available for the surgeon? Theoretical and practical advantages and disadvantages (in French). J Chir (Paris) 144(4):5S35–5S40

Pélissier EP, Monek O, Blum D, Ngo P (2007) The Polysoft patch: prospective evaluation of feasibility, postoperative pain and recovery. Hernia 11:229–234

Berrevoet F, Sommeling C, De Gendt S, Breusegem C, de Hemptinne B (2009) The preperitoneal memory-ring patch for inguinal hernia: a prospective multicentric feasibility study. Hernia 13:243–249

Itani KMF, Fitzgibbons RJ, Awad SS, Duh Q, Ferzli GS (2009) Management of recurrent inguinal hernias. J Am Coll Surg 209:653–658

Koning GG, de Schipper HJP, Oostvogel HJM, Verhofstad MHJ, Gerritsen PG, van Laarhoven KCJHM, Vriens PWHE (2009) The Tilburg double blind randomised controlled trial comparing inguinal hernia repair according to Lichtenstein and the transinguinal preperitoneal technique. Trials 10:89

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Maillart, J.F., Vantournhoudt, P., Piret-Gerard, G. et al. Transinguinal preperitoneal groin hernia repair using a preperitoneal mesh preformed with a permanent memory ring: a good alternative to Lichtenstein’s technique. Hernia 15, 289–295 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-010-0778-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-010-0778-5