Abstract

A 4-year-old girl presented with fever, coughing, and vomiting; followed by unconsciousness. Magnetic resonance imaging showed hyperintense changes in the thalami bilaterally, brain stem, cerebellum, and subcortical cortex. Novel influenza A (H1N1) virus was identified by polymerase chain reaction in patient’s nasopharyngeal swab specimen. We reported a rare case of clinically severe, novel influenza A-associated encephalitis. Novel influenza A should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with seizures and mental status changes, especially during an influenza outbreak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human infection with the novel H1N1 influenza virus, initially popularly termed “swine flu,” was first reported in April 2009. Most patients present with fever, sore throat, and cough. Complications of novel influenza A (H1N1) virus especially affect certain risk groups, such as patients with chronic heart and lung disease, children with underlying medical conditions, and pregnant women. The most common cause of death from the virus is respiratory failure, but other causes of mortality include sepsis, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. Neurologic complications, including seizures, encephalopathy, encephalitis, Reye-like syndrome, focal neurologic deficits, and other neurologic disorders, have been described previously in association with respiratory tract infection with seasonal influenza A or B viruses, but not frequent with swine influenza A (H1N1) virus [1–3].

So far, there are a few cases reported in literature with neurological complications associated with novel virus infection [4–6]. Here, we report a 4-year-old girl with fatal encephalitis due to swine virus infection.

Case report

A 4-year-old girl with chronic renal failure due to vesicoureteral reflux was admitted our hospital with fever, cough, fatigue, and unconsciousness complaints. Her symptoms had started 3 days ago. Two family members also had the same symptoms. Salicylates and salicylate-containing products had not been administered for the last days.

On physical examination, her body weight was 11 kg (<3%), body temperature was 39.5°C, blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg. Her pharynx was hyperemic. Respiratory and cardiovascular systems were normal. She was unconscious. She had mild increased deep tendon reflex and extensor plantar responses. No focal neurological signs were noted.

At the second day of admission, she had generalized tonic–clonic seizures for three times which was controlled by IV phenytoin.

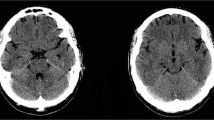

Laboratory studies showed white blood cells of 6,000 × 103 per liter, platelet count of 117,000 × 103 per liter, and hemoglobin level of 8.0 g/dl. Serum electrolytes, bilirubin, metabolic screening of urine and blood were normal. Serum BUN 88 mg/dl, creatinine 1.7 mg/dl, AST/ALT 273/219 U/l, ammonia 177 μmol/l, glucose 23 mg/dl, and prothrombin time 35/1.66 were noted. Moreover, serological studies for Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, rubella virus, hepatitis A–C virus, and toxoplasma gondii were negative. Toxicologic studies were also negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain on the second day showed hyperintense changes in the thalami bilaterally, brain stem, cerebellum, and subcortical cortex (Fig. 1). However, we could not perform lumbar function and electroencephalography because of her poor clinical conduction.

Under the impression of Reye or Reye-like syndrome, she was given intravenous glucose infusion and hypertonic saline treatment. Broad spectrum IV antibiotic (ceftriaxone) and acyclovir treatment were initiated. On the third day, her conduction was deteriorated and intubated patient was mechanically ventilated by conventional mechanical ventilation. Novel influenza A (H1N1) virus was positive on her nasal and throat swabs and started oseltamivir. But she died on the same day.

Discussion

Neurologic complications associated with seasonal influenza have been reported in literature before [1, 3, 5]. Although the majority of the patients had relatively minor symptoms, a small but significant number of them have experienced serious complications, resulting in neurologic sequelae and even death. Small numbers of children with neurologic complications have been reported sporadically in Europe and Canada, whereas reports from the US in the past 60 years have been exceedingly rare [2, 7].

Neurologic complications associated with seasonal influenza in children consist of acute cognitive and behavioral problems, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, encephalitis, and death [1–3]. The interval between the onset of respiratory symptoms and the development of neurologic symptoms in patients with seasonal influenza-related encephalitis varies from 1 to 14 days with a median of 3 days [8]. Infection with seasonal influenza virus can be associated with neurologic complications, but the exact frequency of which these occur with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection is still unknown. Influenza-associated neurologic complications are estimated to account for up to 5% of cases of acute childhood encephalitis or encephalopathy and were reported in 6% of influenza-associated deaths among children during one influenza season in the US [9]. The epidemiology of influenza-associated encephalopathy has been described extensively in Japan, where incidence has appeared to be higher than in other countries [10].

In literature, seasonal influenza virus infection has been associated with a variety of neurologic complications. The neurologic complications associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus was described in four children. This is the first case reporting neurologic complications due to novel influenza A (H1N1) virus [4]. The clinical characteristics of those four cases were aged between 7 and 17 years and were admitted with signs of influenza-like illness and seizures or altered mental status. All four patients fully recovered and had no neurologic sequelae at discharge. In another case, Sánchez-Torrent et al. [5]. described a case of novel influenza A (H1N1) encephalitis in an infant aged 3 months. Similarly, the patient presented a favorable outcome with full recovery within a few days. But our patient was died on the third day of admission. Our patient is the first reported case of novel influenza A (H1N1)-related fatal encephalitis.

The pathogenesis of influenza-related encephalopathy is still unclear, but may involve viral invasion of the CNS, proinflammatory cytokines, metabolic disorders, or genetic susceptibility [8].

Neuroimaging studies in influenza-associated encephalopathy might be normal, but in severe cases, abnormalities including diffuse cerebral edema and bilateral thalamic lesions can be seen [1]. We demonstrated similar lesions in cerebral MRI of our patient. We could detect novel influenza A viral RNA in nasopharyngeal specimens but could not evaluate in CSF.

These findings have suggested that neurologic complications could also appear after novel influenza A virus infection. For patients with respiratory illness and having neurologic signs (unexplained seizures or mental status changes) diagnostic testing for possible etiologic pathogens including novel influenza viruses should done during the influenza season. We considered that respiratory specimens should be sent for appropriate diagnostic testing, and immediately start empirical antiviral therapy, especially in hospitalized patients.

References

Protheroe SM, Mellor DH (1991) Imaging in influenza A encephalitis. Arch Dis Child 66:702–705

McCullers J, Facchini S, Chesney P et al (1999) Influenza B virus encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis 28:898–900

Maricich SM, Neul JL, Lotze TE et al (2004) Neurologic complications associated with influenza A in children during the 2003–2004 influenza season in Houston, Texas. Pediatrics 114:e626–e633

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009) Neurologic complications associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in children—Dallas, Texas, May 2009. MMWR 58:773-778

Sánchez-Torrent L, Triviño-Rodriguez M, Suero-Toledano P et al (2010) Novel influenza A (H1N1) encephalitis in a 3 month-old infant. Infection 38:227–229

Wang GF, Li W, Li K (2010) Acute encephalopathy and encephalitis caused by influenza virus infection. Curr Opin Neurol 23:305–311

Newland J, Romero J, Varman M et al (2003) Encephalitis associated with influenza B virus infection in 2 children and a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 36:e87–e95

Amin R, Ford-Jones E, Richardson S et al (2008) Acute childhood encephalitis and encephalopathy associated with influenza. a prospective 11 year review. Pediatr Infect Dis J 27:390–395

Bhat N, Wright JG, Broder KR et al (2005) Influenza-associated deaths among children in the United States, 2003–2004. N Engl J Med 353:2559–2567

Morishima T, Togashi T, Yokota S et al (2002) Encephalitis and encephalopathy associated with an influenza epidemic in Japan. Clin Infect Dis 35:512–517

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Incecik, F., Ozlem Hergüner, M., Altunbasak, S. et al. Fatal encephalitis associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in a child. Neurol Sci 33, 677–679 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-011-0839-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-011-0839-2