Abstract

Background

Peritoneal carcinomatosis is common after curative resection of gastric cancer. Intraperitoneal administration of paclitaxel (PTX) is known to control ovarian peritoneal metastases.

Patients and methods

Patients with either linitis plastica or T4 cancer with high risk of peritoneal metastasis or recurrence but whose cancer was considered resectable were preregistered. After their cancer had been confirmed intraoperatively as resectable, the patients were randomized into either group A (PTX at 60 mg/m2 intraperitoneally on the day of surgery and on days 14, 21, 28, 42, 49, and 56) or group B (PTX at 80 mg/m2 administered intravenously by the identical schedule) before being treated by evidence-based chemotherapy. The primary end point was the 2-year survival rate. Safety, the secondary end point, was also analyzed. The study has been registered as UMIN000002957.

Results

Of 177 preregistered patients, 83 underwent treatment (39 by intraperitoneal administration and 44 by intravenous administration). There was no difference in patient demographics between the two groups. The incidences of surgical complications were similar between the groups, except for transient bowel obstruction observed exclusively in group A. The relative dose intensity of PTX was 81.4 % for group A and 76.3 % for group B. There was one death due to pulmonary thrombosis and a case of anaphylaxis that led to termination of the protocol treatment (group B). Other adverse events were mild and manageable.

Conclusions

Intraperitoneal administration of PTX from the day of gastrectomy did not result in a higher incidence of surgical complications and adverse reactions when compared with intravenous administration of PTX.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer remains the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide, although the incidence has declined over the last decade [1]. A large proportion of patients have advanced or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis because of lack of symptoms specific to this disease. Cancer cells that are exfoliated from the primary tumor can be scattered into the peritoneal cavity once cancer invades the serosa, and peritoneal carcinomatosis as a consequence is a common type of metastasis that renders the disease incurable [2]. Effective means of treating patients with peritoneal disease by systemic administration of anticancer drugs has not been reported.

Peritoneal metastases can be observed on laparotomy or on laparoscopy as minute deposits adhered to the peritoneal surface, but are often undetectable preoperatively by conventional imaging modalities [3]. Patients with peritoneal metastases have seldom been eligible for studies that aim to evaluate new and promising drugs, because the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents is generally elucidated through treatment of patients with measurable lesions. The efficacy of intraperitoneal administration of paclitaxel (PTX) has been suggested by some phase II trials and pharmacokinetic studies in gastric cancer [4–6], but less convincingly than in ovarian cancer [7], another cancer type that is commonly associated with peritoneal metastases. To date, no comparison of intraperitoneal versus intravenous administration of PTX has been attempted for gastric cancer. Other treatment strategy involving intraperitoneal administration of anticancer drugs have either been unsuccessful [8] or technically demanding, with rather high morbidities and mortalities [9].

A multi-institutional randomized phase II trial was conducted to prove the superiority of postoperative intraperitoneal administration of PTX over intravenous administration of PTX in preventing the development of peritoneal carcinomatosis among gastric cancer patients who underwent gastrectomy. This trial aimed to form a theoretical basis for the implementation of intraperitoneal administration of PTX into various combination chemotherapy regimens in future clinical trials. The duration of the protocol treatment with single-agent PTX was made brief so as to allow a prompt transition to the evidence-based systemic adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 [10, 11] or the S-1 and cisplatin combination [12, 13]. As a preliminary report of this trial, we report herein a safety analysis of intraperitoneal versus intravenous administration of PTX that begins on the day of radical surgery for gastric cancer, in addition to the feasibility of intraperitoneal administration via an indwelling catheter.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility and randomization

The concept of the study and a synopsis of the study protocol have already been published [14]. Patients with resectable advanced gastric cancer with a particularly high risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis were eligible. Patients who fulfilled the following criteria were eligible for preoperative registration:

-

1.

Histologically proven adenocarcinoma of the stomach

-

2.

Macroscopically type 3 cancer with a tumor diameter of 8 cm or more as estimated by endoscopic examination or barium swallow, type 4 (linitis plastica) cancer [3, 15], or patients suspected of having small quantities of peritoneal deposits or those with positive peritoneal washing cytology findings

-

3.

No metastases to the cervical, mediastinal, para-aortic, or other distant lymph nodes or to the distant organs such as the liver and lung, or ascites that occupy areas beyond the pelvic cavity as found by computerized tomography that scanned from the pelvis to the thorax

-

4.

No clinical manifestations suggestive of distant metastases

-

5.

No history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy

-

6.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–1

-

7.

Age older than 20 years

-

8.

Sufficient organ functions in terms of the following laboratory data within 7 days from surgery: white blood cell count between 3000/mm3 and 12,000/mm3, neutrophil count of 1500/mm3 or greater, platelet count greater than 100,000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of 100 IU/L or lower, total bilirubin level of 1.5 mg/dL or lower, serum creatinine level of 1.5 mg/mL or lower, serum albumin level greater than 3.0 g/dL

-

9.

No severe arrhythmia

-

10.

Written consent obtained from the patient after the patient has been thoroughly informed about the nature of the study

Exclusion criteria included (1) ischemic heart disease and arrhythmia needing treatment or myocardial infarction within 6 months of onset, (2) liver cirrhosis, (3) interstitial pneumonitis, (4) gastrointestinal bleeding in need of repeated blood transfusion, (5) uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, (6) bowel obstruction rendering treatment with oral drugs impractical, (7) active synchronous cancer or disease-free metachronous cancer within 5 years of onset, (8) signs of acute infection or inflammatory disease, (9) need for systemic treatment with corticosteroids, (10) hypersensitivity to Cremophor EL, (11) women who are pregnant, contemplating pregnancy, or amid breast-feeding, (12) mental disorders which may affect the ability or willingness to provide informed consent, (13) history of severe hypersensitivity to any drugs, (14) history of alcoholic anaphylaxis, (15) peripheral neuropathy, (16) patients otherwise considered as inappropriate for inclusion in the study.

On laparotomy, patients who fulfilled all the following criteria were registered via telephone call to the data center and proceeded to randomization: (1) considered as having resectable disease; (2) having either i) type 3 cancer with a diameter of 8 cm or more or type 4 (linitis plastica) cancer, ii) small quantities of peritoneal seeding that do not discourage surgeons from proceeding with gastrectomy, or iii) intraperitoneal free cancer cells detected in the peritoneal washes; (3) placement of an indwelling catheter for intraperitoneal administration is considered possible. Patients were randomized during surgery to one of the two treatment groups by a centralized dynamic method using the following factors as balancing variables: macroscopic type (types 3 and 4/others), curability of surgery (R0 and R1/R2), age (younger than 75 years/75 years or older), and institution.

Surgery

Total or distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection was proposed. Splenectomy was not mandatory except when the primary lesion occupied the greater curvature of the upper third of the stomach. Pancreatectomy was performed only in the event of direct cancer invasion. The method of reconstruction was to be decided at the discretion of the surgeon. Placement of the indwelling catheter was carefully performed by the method of Markman and Walker [16] so as to avoid various catheter-related adverse events.

Intraoperative and postoperative chemotherapy

The first ten patients were to receive intraperitoneal administration of PTX exclusively as a feasibility test. These patients were to be evaluated only for toxicity and would not be included in the survival analysis. If at least four successful intraperitoneal deliveries could not be conducted in at least five of the ten patients, the study would have to be terminated and the method reconsidered.

In the next step, the patients were to be randomized to one of the following treatment arms during gastrectomy. In group A, patients received PTX intraperitoneally at 60 mg/m2 on the day of surgery (day 1) and on days 15, 22, 29, 43, 50, and 57. The dose of PTX administered intraperitoneally is based on a phase I trial performed in the USA for ovarian cancer patients [17]. PTX was dissolved in 1000 mL saline, and its delivery on the day of surgery was performed on closure of the abdomen through a catheter temporarily placed through the surgical incision. Use of the indwelling catheter was avoided at this time. Abdominal drains placed during surgery had to be clamped for 24 h after the administration. In the remaining six intraperitoneal treatments, PTX dissolved in 1000 mL saline was delivered through the indwelling catheter. Before the intraperitoneal treatment, 500 mL saline was administered through the catheter to ensure that the delivery system was intact and there was no leakage outside the peritoneal cavity. In group B, patients received PTX intravenously at 80 mg/m2 on the day of surgery (day 1) and on days 15, 22, 29, 43, 50, and 57. Weekly intravenous administration at this dose has been explored in various trials, both in the advanced/metastatic setting [18] and in the postoperative adjuvant setting [19].

These treatments were to be followed after 2–3 weeks either by S-1 monotherapy [10] or by a combination of S-1 and cisplatin therapy [12], which were standard systemic chemotherapies for advanced gastric cancer at the time the trial started. S-1 monotherapy was recommended after R0/R1 resection and S-1 and cisplatin combination therapy was recommended after R2 resection, but the selection was left to the discretion of the physician in charge. When patients randomized to group A failed to receive intraperitoneal chemotherapy because of catheter-related complications, they were expected to continue with the intravenous PTX therapy according to the predetermined schedule so that the subsequent systemic chemotherapy would be started at the same time as in other patients.

Study design and statistical considerations

The primary end point was the 2-year survival rate. The secondary end points were safety, progression-free survival, and overall survival. The current study is a randomized phase II trial applying a selection design as proposed by Simon [20]. The primary analysis in this study is aimed at selecting an appropriate treatment arm for further evaluation, and the sample size was calculated on the hypothesis that the 2-year overall survival rate in the intravenous treatment arm, estimated to be 30–40 %, could be improved by 10 % in the intraperitoneal treatment arm. The selection probability is estimated to be 82–83 % when the total sample size is 80 and 84–85 % when the sample size is 100. Thus the total sample size to be randomized was set at 90 patients.

Chi-squared analysis was used to evaluate differences in clinicopathologic variables and the incidence of adverse events between the groups. The Mann–Whitney test was used to detect differences in continuous variables.

The study has been registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry as UMIN000002957. Because intraperitoneal PTX therapy has not been approved in Japan, the trial was conducted as Advanced Medical Treatment B under approval of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. This meant that medical expenses other than that of PTX for intraperitoneal administration were covered by the national medical insurance. PTX for intraperitoneal administration was supplied by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Results

Feasibility study

A summary of the feasibility part of the study follows: PTX was delivered intraperitoneally to two male and four female patients aged 59.5 years (range 44–75 years). The tumor diameter was large at 89.5 mm (range 40–150 mm), with peritoneal metastasis in four patients and all patients having six or more nodal metastases. Total gastrectomy was performed in five patients (splenectomy in two patients) and distal gastrectomy in one patient. Grade 3 or greater hematological toxicity was observed in three patients (one with leukopenia and three with neutropenia), and grade 2 or greater nonhematological adverse events included hypoalbuminemia in two patients, elevation of AST/ALT levels in two patients, fatigue in two patients, anorexia in two patients, nausea in one patient, diarrhea in two patient, elevation of bilirubin level in one patient, arrhythmia in one patient, and taste disturbance in one patient. All adverse events were controllable and there were no deaths. One patient had an abdominal abscess through pancreatic fistula and needed percutaneous drainage. Thus intraperitoneal therapy had to be abandoned after three cycles. The remaining five patients completed all seven cycles of intraperitoneal therapy and the predetermined criterion (at least four successful intraperitoneal deliveries in at least five patients) to proceed to a randomized phase II trial was already fulfilled at this stage. This and slow accrual led us to omit registration of the remaining four patients and move on to the randomized trial.

Patients registered for the randomized trial

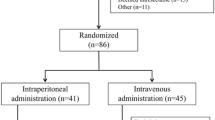

Between June 2011 and November 2014, 177 patients were registered preoperatively in the randomized phase II part of the study. On laparotomy, 91 patients were found to be ineligible (65 because of lack of peritoneal deposits and negative peritoneal washing cytology findings, 15 because of the surgeon’s decision to close the abdomen without performing gastrectomy, and 11 for miscellaneous other reasons) and the remaining 86 patients were randomized to the treatment groups. Unfortunately, the initially planned sample size of 90 patients was not reached because of slow accrual (there was a time limit in the Advanced Medical Treatment B scheme). Eighty-three patients eventually underwent the treatment in accordance with the protocol (39 randomized to group A and 44 randomized to group B) and were eligible for analysis of the adverse events (Fig. 1).

Patient disposition

The patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. Various prognostic factors were well balanced between the groups. Most patients had advanced-stage cancer, and more than 75 % of the patients had either type 3 cancer with a diameter of 8 cm or more or type 4 cancer (linitis plastica) and had a high risk of peritoneal metastasis. Histopathologically, cancer invaded the serosa (pT4) in 28 of the 39 patients in group A and 33 of the 44 patients in group B. Furthermore, 27 of the 39 patients in group A and 32 of the 44 patients in group B had more than six nodal metastases (pN3). Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis was observed in six and ten patients in groups A and B respectively, and peritoneal washing cytology findings were positive in 14 and 12 patients in groups A and B respectively.

Outcomes after surgery

The median operating time was 25 min longer for group A, possibly reflecting the time taken for insertion of the indwelling catheter and subsequent intraperitoneal administration of PTX. The difference, however, was not statistically significant. Postoperative hospital stay was 17 days for group A and 15 days for group B (p = 0.0376). The incidences of surgical complications were similar between the groups (Table 2). The only exception was that four cases of bowel obstruction occurred exclusively in group A (p = 0.0123). One of these cases was due to stenosis of the jejunojejunal anastomosis, and resolved after decompression and endoscopic dilatation. Other cases of bowel obstruction occurred between 1 and 3 weeks after surgery. All patients recovered swiftly, one by decompression with a nasogastric tube for 2 days, and the other two by conservative measures such as fasting and medication. These three cases of bowel obstruction could have been attributable to intraperitoneal PTX therapy. During the postoperative follow-up, two more patients, also in group A, underwent surgery for bowel obstruction. However, the cause of mechanical ileus was clearly identified as the adhesive string structure which was dissected in the laparoscopic procedure in each of the cases, and it is unlikely that intraperitoneal PTX therapy was the cause.

Treatment delivery and compliance

In group A the numbers of intraperitoneal administrations given were one in five patients, two in one patient, four in two patients, six in two patients. and seven in 29 patients, for a completion rate of 74.4 %. In group B the numbers of intravenous administrations given were one in five patients, three in two patients, four in two patients, six in three patients, and seven in 32 patients, for a completion rate of 72.7 %. The patient in group A who received only two intraperitoneal administrations actually suffered from occlusion of the indwelling catheter, and the remaining five administrations were given intravenously as had been prespecified in the protocol. This was the only catheter-related problem we experienced in this trial, and no other patients in group A received PTX intravenously. Other reasons for termination of the protocol treatment were surgical complications in five patients, refusal by one patient, the physician’s choice for one patient, a severe adverse event in one patient, and failure to fulfill the criteria in terms of laboratory data for drug administration in one patient for group A, and severe adverse events in four patients, surgical complications in three patients, failure to fulfill the criteria for drug administration in three patients, and refusal by two patients for group B. The relative drug intensity of PTX was 81.4 % in group A and 76.3 % in group B.

Adverse events

There was one death due to pulmonary thrombosis on the 44th postoperative day after completion of four intravenous administrations of PTX and one case of anaphylaxis at the first intravenous administration that led to immediate termination of the protocol treatment. Other adverse events were mild and manageable (Table 3). Leukopenia of all grades occurred more frequently in group B (p = 0.0375), but the incidence of febrile neutropenia was similar between the two groups. When the six patients who underwent intraperitoneal PTX therapy in the feasibility study were added to the 39 patients in group A and analyzed, Grade 3 or greater leukopenia and neutropenia occurred in 16 and 24 % or patients respectively, whereas common grade 2 or greater nonhematological events were hypoalbuminemia (80 %), elevation of AST level (31 %), elevation of ALT level (29 %), anorexia (27 %), fatigue (22 %), elevation of bilirubin level (15 %), nausea (11 %), abdominal pain (9 %), and diarrhea (9 %).

Discussion

Peritoneal carcinomatosa had long been the commonest pattern of recurrence after radical surgery in the Far East [21, 22]. More recently, the commonest site of recurrence among 817 patients identified in the US Gastric Cancer Collaborative database to have undergone curative intent resection was reported to be peritoneal (n = 92), with peritoneal-only metastasis found in 47 patients (19.3 %) [23]. Thus prevention of peritoneal metastasis is an important issue after the surgical treatment for gastric cancer worldwide. Methods to exterminate intraperitoneal cancer cells range from extensive intraoperative lavage with saline [24] to hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) [9, 25]. It is doubtful whether mere lavage could cure established metastatic foci on the peritoneum, whereas whether the expensive and potentially morbid HIPEC approach is of any added clinical value remains to be proven in a prospective randomized study. Additionally, HIPEC usually offers a single opportunity for intraperitoneal exposure to chemotherapy and is considered as an adjunct to an aggressive cytoreductive surgery [25], after which the formation of severe adhesions is expected throughout the abdominal cavity. In contrast, repeated intraperitoneal administration of anticancer drugs would seem a rational approach. It is of note, however, that a single intraperitoneal administration of cisplatin did not have any impact on survival of patients with serosa-positive cancer [8], partially because cisplatin is rapidly absorbed from the peritoneal cavity and enters the systemic circulation. It has been documented that PTX delivered intraperitoneally reaches and maintains an extremely high intraperitoneal concentration through slow exit from the peritoneal cavity [4, 5]. Curiously, PTX is known to enter the peritoneal cavity and reach a therapeutic concentration even when given intravenously [26], and intravenous administration of PTX had been believed to be suitable in the treatment of peritoneal disease [27]. Thus a head-to-head comparison of intraperitoneal versus intravenous administration of PTX along with safety analysis of the intraperitoneal treatment was considered an essential first step in the process of developing a new strategy based on intraperitoneal administration. In this study, weekly intraperitoneal PTX administration at 60 mg/m2 from the day of surgery was found to be safe and feasible.

On the other hand, a lengthy spell of intraperitoneal PTX therapy in the absence of systemic chemotherapy could render the treatment strategy vulnerable in controlling micrometastases disseminated through hematogenous and lymphatic metastatic pathways, given that PTX delivered intraperitoneally does not reach a clinically meaningful serum concentration [4]. Thus the PTX phase of the treatment was limited to 8 weeks in the current study so that evidence-based systemic chemotherapy could be offered to the participants thereafter. In addition, PTX is known to have limited capacity to directly penetrate into tumor tissue [17]. Therefore accrual of patients who are likely candidates for R0/R1 resection rather than R2 resection was encouraged. Because of the anticipated difficulty in preoperatively identifying patients suitable for the trial, only 86 of 177 patients who were initially considered as candidates eventually underwent intraoperative randomization, and 83 were treated in accordance with protocol. This led to adequate patient selection, and 74 of these patients (89 %) received R0/R1 resection. Survival analysis of the trial is eagerly awaited.

Another group of researchers conducted a phase I trial to find the optimal dose for combining intraperitoneal PTX therapy with systemic chemotherapy (a combination of S-1 and intravenously administered PTX) [5]. After a successful phase II trial with gastric cancer patients whose disease was deemed unresectable becasue of confirmed peritoneal metastasis, they conducted a randomized phase III trial with the same population to compare this hybrid regimen with the S-1 and cisplatin combination [6], the current standard of care for treatment of unresectable gastric cancer. Although survival analysis of that trial is about to be conducted, we believe that the current study remains useful to reinforce the rationale for the use of intraperitoneally administered PTX alone or in combination with other drugs to control the peritoneal disease postoperatively.

Importantly, this study looks at safety of intraperitoneal PTX therapy during and after gastrectomy. Investigators were initially concerned about the potential harm caused by intraperitoneal treatment during the early postoperative period, although it had been reported as feasible for ovarian cancer [28]. Fortunately, there was no significant increase in the incidence of surgical site infection in the current series. The incidences of most other surgical complications were similar between the two groups, with the exception of bowel obstruction, where all four cases occurred in the intraperitoneal PTX therapy group. However, the obstruction was transient in all cases, with three of four patients completing all seven intraperitoneal administrations and the remaining case receiving six administrations. The published surgical considerations on insertion of indwelling catheters [12] were rigorously observed, and the drug delivery devices functioned adequately in most cases, one case of catheter occlusion being the only exception. No perforation, infection, or other catheter-related damage to the intraperitoneal organs has been reported to date. The commonest adverse events in all patients were hypoalbuminemia, followed by elevation of AST and ALT levels, but these could also be attributable to surgery with lymphadenectomy and the use of other drugs related to general anesthesia and postoperative management. Adverse events commonly associated with chemotherapy such as hematological toxicity and fatigue were observed in both arms but were mostly mild and manageable. Given the pharmacokinetics in the patients who received intraperitoneal PTX therapy for malignant ascites where the serum concentration of PTX did not reach a clinically relevant level [4], it was intriguing to find that the incidence of febrile neutropenia was similar in the intraperitoneal treatment and intravenous treatment groups. However, there is a possibility that the pharmacokinetics is different in patients who underwent radical surgery. Although no pharmacokinetic data were obtained in the current study, Imano et al. [29] evaluated the pharmacokinetics of a single administration of PTX at 80 mg/m2 after D2 dissection and found that the serum level did not reach the cytotoxic threshold in most cases. Nevertheless, the mean peak serum value of 11 patients of 45.2 ng/mL in that study was higher than what we found in the treatment of inoperable patients [4]. From these findings taken together, bone marrow toxicity should not be taken lightly in patients who received intraperitoneal PTX therapy on the day of or shortly after radical gastrectomy. Abdominal pain was the dose-limiting adverse event in the phase I trial of weekly intraperitoneal PTX therapy for ovarian cancer patients [17], but was not particularly common when these patients were compared with patients with received intravenous PTX therapy.

The small sample size is one of the weaknesses of this study. A chief reason for this was that there were several requirements for a medical institution to join the Advanced Medical Treatment B scheme. In addition, patients fulfilling the criteria of resectable gastric cancer with a particularly high risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis were rather uncommon. Another potential weakness may be that this study compares intraperitoneal PTX therapy, the new proposal, with intravenous PTX therapy, which has not been acknowledged as a standard treatment in the postoperative adjuvant setting. This may not be a serious problem, however, considering the results of a pivotal phase III trial to explore a sequential use of intravenous PTX therapy followed by S-1 therapy as postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for serosa-positive (T4a or T4b) gastric cancer [30]. In that trial, the 3-year disease-free survival achieved with sequential therapy does not seem inferior to that achieved with S-1 monotherapy, the standard of care.

To conclude, PTX at a weekly dose of 60 mg/m2 was safely administered intraperitoneally from the day of surgery and did not result in a higher incidence of surgical complications and adverse reactions when compared with intravenous PTX therapy delivered by the identical weekly schedule. Survival results in favor of intraperitoneal PTX therapy could pave a way for further exploitation of intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86.

Kodera Y. Gastric cancer with minimal peritoneal metastasis: is this a sign to give up or to treat more aggressively? Nagoya J Med Sci. 2013;75:3–10.

Miki Y, Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. Staging laparoscopy for patients with cM0, type 4 and large type 3 gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2015;39:2742–7.

Kodera Y, Ito Y, Ito S, Ohashi N, Mochizuki Y, Yamamura Y, et al. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel: a possible impact of regional delivery for prevention of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:960–3.

Ishigami H, Kitayama J, Otani K, Kamei T, Soma D, Moyato H, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic study of weekly intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with S-1 for advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2009;76:311–4.

Ishigami H, Kitayama J, Kaisaki S, Hidemura A, Kato M, Otani K, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with S-1 for advanced gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:67–70.

Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Baergen R, Lele S, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43.

Miyashiro I, Furukawa H, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Nashimoto A, Nakajima T, et al. Randomized clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with intraperitoneal and intravenous cisplatin followed by oral fluorouracil (UFT) in serosa-positive gastric cancer versus curative resection alone: final results of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial JCOG9206-2. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:212–8.

Di Vita M, Cappellani A, Piccolo G, Zanghi A, Cavallaro A, Bertola G, et al. The role of HIPEC in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: between lights and shadows. Anticancer Drugs. 2015;26:123–38.

Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810–20.

Kodera Y, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Kondo K, Koshikawa K, Suzuki N, et al. A phase II study of radical surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy with S-1 for gastric carcinoma with free cancer cells in the peritoneal cavity (CCOG0301 study). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1158–63.

Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215–21.

Kurimoto K, Ishigure K, Mochizuki Y, Ishiyama A, Matsui T, Ito S, et al. A feasibility study of postoperative chemotherapy with S-1 and cisplatin (CDDP) for stage III/IV gastric cancer (CCOG1106). Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:354–9.

Kodera Y, Imano M, Yoshikawa T, Takahashi N, Ysuburaya A, Miyashita Y, et al. A randomized phase II trial to test the efficacy of intra-peritoneal paclitaxel for gastric cancer with high risk for the peritoneal metastasis (INPACT trial). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:283–6.

Iwasaki Y, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Nakamura K, Sano T, Katai H, et al. Phase II study of preoperative chemotherapy with S-1 and cisplatin followed by gastrectomy for clinically resectable type 4 and large type 3 gastric cancers (JCOG0210). J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:741–5.

Markman M, Walker JL. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy of ovarian cancer: a review, with a focus on practical aspects of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:988–94.

Francis P, Rowinsky E, Schneider J, Hales T, Hoskins W, Markman M. Phase I feasibility and pharmacologic study of weekly intraperitoneal paclitaxel: a Gynecologic Oncology Group pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2961–7.

Kodera Y, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Fujitake S, Koshikawa K, Kanyama Y, et al. A phase II study of weekly paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer (CCOG0302 study). Anticancer Res. 2007;27:2667–71.

Kobayashi M, Tsuburaya A, Nagata N, Miyashita Y, Oba K, Sakamoto J. A feasibility study of sequential paclitaxel and S-1 (PTX/S-1) chemotherapy as postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:114–9.

Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10.

Maehara Y, Hasuda S, Koga T, Tokunaga E, Kakeji Y, Sugimachi K. Postoperative outcome and sites of recurrence in patients following curative resection of gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:353–7.

Yoo C, Noh S, Shin D, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:236–42.

Spolverato G, Ejaz A, Kim Y, Squires MH, Poultsides GA, Fields RC, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence after curative intent resection for gastric cancer: a United States multi-institutional analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:664–75.

Kuramoto M, Shimada S, Ikeshima S, Matsuo A, Yagi Y, Matsuda M, et al. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage as a standard prophylactic strategy for peritoneal recurrence in patients with gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250:242–6.

Roviello F, Caruso S, Neri A, Marrelli D. Treatment and prevention of peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: overview and rationale. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1309–16.

Kobayashi M, Sakamoto J, Namikawa T, Okamoto K, Okabayashi T, Ichikawa K, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of paclitaxel in malignant ascites from advanced gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1412–5.

Nishina T, Boku N, Gotoh M, Shimada Y, Hamamoto Y, Yasui H, et al. Randomized phase II study of second-line chemotherapy with best available 5-fluorouracil versus weekly paclitaxel in far advanced gastric cancer with severe peritoneal metastases refractory to 5-fluorouracil-containing regimens (JCOG0407). Gastric Cancer. 2015. doi:10.1007/s10120-015-0542-8.

Senga RA, Dottino PR, Jennings TS, Cohen CJ. Fesibility of intraoperative administration of chemotherapy for gynecologic malignancies: assessment of acute postoperative morbidity. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;48:227–31.

Imano M, Imamoto H, Itoh T, Satou T, Peng YF, Yasuda A, et al. Safety of intraperitoneal administration of paclitaxel after gastrectomy with en-bloc D2 lymph node dissection. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:43–7.

Tsuburaya A, Yoshida K, Kobayashi M, Yoshino S, Takahashi M, Takiguchi N, et al. Sequential paclitaxel followed by tegafur and uracil (UFT) or S-1 versus UFT or S-1 monotherapy as adjuvant chemotherapy for T4a/b gastric cancer (SAMIT): a phase 3 factorial randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:886–93.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported, in part, by the Epidemiological and Clinical Research Information Network, a nonprofit organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Yasuhiro Kodera has received grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Company, Taiho Pharmaceutical Company, Sanofi Aventis, Bristol-Meyers Squib, Merck, Yakult, Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda, Eli Lilly Japan, and Pfizer and grants from Ono Pharmaceutical Company and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Takaki Yoshikawa has received grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Company, Yakult, Eli Lilly Japan, and Ono Pharmaceutical Company, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, Nihon Kayaku, and Novartis, and personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical Company and Takeda outside the submitted work. Satoshi Morita has received personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squib outside the submitted work.

Statement of human rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964 and later versions).

Informed consent

Informed consent for their being included in the study was obtained from all patients who took part in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kodera, Y., Takahashi, N., Yoshikawa, T. et al. Feasibility of weekly intraperitoneal versus intravenous paclitaxel therapy delivered from the day of radical surgery for gastric cancer: a preliminary safety analysis of the INPACT study, a randomized controlled trial. Gastric Cancer 20, 190–199 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-016-0598-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-016-0598-0