Abstract

Objectives

Siewert type II esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma encompasses both gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (GCA) and Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma (BEA) due to short-segment Barrett’s esophagus. We compared these two types of Siewert type II esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma in terms of background factors and clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

Methods

We enrolled 139 patients (142 lesions) who underwent ESD from 2006 to 2014 at our institution. Background factors evaluated were age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking, drinking, double cancer, and endoscopic findings. Clinical outcomes evaluated were procedure time, en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate, and adverse events.

Results

There were 87 GCA lesions (61.2%) and 55 BEA lesions. Features of BEA [55 lesions (38.8%)] included a younger age, small diameter, and a protruding type, along with a high frequency of esophageal hiatal hernia and less mucosal atrophy. There were no significant differences in lifestyle-related background factors between the GCA and BEA groups. Curative resection rate was greater for GCA (81%) than for BEA (66%) (P = 0.01). There were no serious adverse events in either group. Among the factors for noncurative resection, lymphovascular invasion and depth of invasion were greater for BEA (33.3 vs. 7 and 20.7 vs. 8.2%, respectively (P < 0.01). Of the noncured patients, 70% underwent additional surgery and none had postoperative lymph node metastasis.

Conclusions

Siewert type II adenocarcinoma encompasses two types of cancers with different etiologies: GCA and BEA. Although there are no significant differences in lifestyle-related background factors between GCA and BEA, BEA is a risk factor for noncurative resection via ESD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For Japanease Men, the morbidity rate of gastric cancer was highest in 2014 [1], but there are no such data on esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma (EGJA). Kusano et al. reported that, compared with 40 years ago, the proportion of all gastric cancers that are EGJAs is increasing, as is the proportion categorized as Siewert type II [2]. Furthermore, the westernization of dietary habits has led to increased obesity and an increased frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease, which is associated with a decreased frequency of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, suggesting in turn that the incidence of EGJA has also increased [2–4].

There are two classification systems for EGJA in Japan. The Nishi classification defines EGJA as a cancer in which the top and the bottom of the center of the cancer are less than 2 cm from the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). This classification includes adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, as defined by the guidelines of the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer [5]. On the other hand, the Siewert classification defines EGJA as a true carcinoma of the cardia arising immediately at the EGJ (Siewert type II) [6]. Both gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (GCA) and Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma (BEA) due to short-segment Barrett’s esophagus are included in each classification. Barrett’s esophagus can be classified as either long segment (LSBE: length of BE >3 cm) or short segment (SSBE: length of BE <3 cm). In Asian countries such as Japan [7], most cases of BE are SSBE rather than LSBE, which is more commonly seen in Western countries. The prevalence of endoscopically suspected BE in Western countries is reported to be 1–7% [8]. In contrast, in Asian countries, the prevalence of endoscopically suspected BE was reported to be 1–5% [9].

The main cause of GCA is H. pylori infection and mucosal atrophy [10–12], whereas BEA results mainly from a high body mass index (BMI) and Barrett’s esophagus [13]. Several reports have shown that BEA is generally caused by a high BMI (especially ≥30 kg/m2) in Europe and the United States [13, 14]. Thus, GCA and BEA have different etiologies.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early cancer is limited by the possible incidence of regional lymph node metastasis. It is unclear whether the frequencies of lymph node metastasis are similar for GCA and BEA, given that they have different etiologies. At our hospital, when performing ESD, we utilize the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma guidelines for GCA, as follows: (1) tumor invasion is confined to the intramucosal layer (T1a) and pathology shows a differentiated-type adenocarcinoma, mainly composed of well-to-moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with no ulceration; (2) a T1a tumor with a maximum diameter of ≤30 mm, with pathology showing a differentiated-type adenocarcinoma with ulceration; (3) a T1a tumor with a maximum diameter of ≤20 mm, pathology showing an undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, mainly composed of poorly differentiated and/or signet-ring cell carcinoma with no ulceration; (4) a T1b (SM1) tumor with a maximum diameter of ≤30 mm, with pathology showing a differentiated-type adenocarcinoma [15]. However, we use the Japanese Esophageal Cancer Guidelines [16] for BEA due to short-segment Barrett’s esophagus, as follows: a differentiated-type adenocarcinoma within the lamina propria mucosae (T1a-LPM); a relative adaptation is to include tumors with an invasion depth to the deep muscularis mucosa (DMM) and within 200 μm from the muscularis mucosa (MM) [5]. This guideline is actually based on squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic therapy in the region of the EGJ have been reported in Japan [17]; however, few reports have compared GCA and BEA in terms of clinical outcomes of endoscopic therapy and background factors. The aim of the present study was therefore to perform this comparison of the two types of Siewert type II esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma.

Methods

Patients

The present study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by our institutional review board (registry no: 2015-1159), and involved human participants. We obtained comprehensive written informed consent for the study before ESD was performed. Between January 2006 and December 2014, 3132 patients underwent endoscopic therapy for gastric and esophageal neoplasms at our hospital.

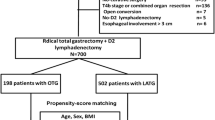

Ultimately, 139 patients with early EGJA histopathologically confirmed by expert pathologists (HK, NY) were enrolled. Our selection criteria were diagnosis of adenocarcinoma from January 2006 to December 2014 and Siewert type II adenocarcinoma (center of cancer within 2 cm of the EGJ on the gastric side or within 1 cm of the EGJ on the oral side). We excluded patients with a histopathologic confirmation of squamous cell carcinoma, those with Siewert type I (center of cancer within 1–5 cm of the EGJ on the oral side) and III (center of cancer more than 2–5 cm from the EGJ on the gastric side) adenocarcinomas, and those with invasion to the muscularis propria or deeper. Figure 1 shows a flowchart for patient selection.

Definitions of Barrett’s esophagus, gastric cardia, and curative resection

For the condition to be considered Barrett’s esophagus, one of the following histological criteria had to be met: esophageal glands, squamous island, double layer of MM, and columnar-lined intestinal metaplasia. Endoscopic criteria were: (a) upper limit of the gastric fold and (b) end of the lower esophageal palisade vessels [18–21]. When the cancer was shown histologically after ESD to arise from Barrett’s esophagus, it was defined as BEA [3]. On the other hand, GCA was considered to arise from the cardia or the fundic gland mucosa of the stomach. Therefore, for the condition to be considered GCA, it had to be located on the anal side of the EGJ line and there had to be no histological findings of Barrett’s esophagus after ESD.

An en bloc resection was defined as resection in one piece with histologically cancer-free margins. A curative resection of BEA was defined as en bloc resection within a T1a-LPM invasion depth, and a relatively curative resection as within a DMM invasion depth and within 200 μm of the SM without lymphovascular invasion [5]. SM2 defines that tumor invasion is >0.2 mm from the muscularis mucosa in BEA. Curative resection for GCA was defined as en bloc resection without lymphovascular invasion that fulfilled the following criteria, in accordance with the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma [15]: intramucosal differentiated adenocarcinoma, regardless of tumor size, without ulceration; intramucosal differentiated adenocarcinoma less than 30 mm in size with ulceration; or minute submucosal differentiated adenocarcinoma (within 500 μm of the MM) less than 30 mm in size; intramucosal undifferentiated adenocarcinoma less than 20 mm in size without ulceration. SM2 defines that tumor invasion is >0.5 mm from the muscularis mucosa in GCA.

Data collection

All data were identified from a review of the relevant medical records and/or imaging. Background factors were age, sex, BMI, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking, drinking, and rates of double cancer and metachronous cancer.

Double cancer was defined as cases where the patient had already experienced another cancers before they were treated for BEA or GCA. Metachronous cancer was defined as the detection of another region from one year after the first treatment until December 2014 [22]. The standard follow-up method in our institute consisted of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) every 6 months during the first year after ESD; EGD was carried out annually after the first year.

Endoscopic findings included maximum diameter, macroscopic type, pathology, rate of regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) [23], and esophageal hiatal hernia. RAC is visible as numerous minute red points in the corpus of an uninfected stomach, is searched for at the lesser curvature of the lower body of the stomach, and is not visible in H. pylori gastritis [23]. Intestinal metaplasia was defined as the appearance of a light blue crest on the epithelial surface in magnifying endoscopic findings [24] or the presence of goblet cells, absorptive cells, and cells resembling colonocytes in pathological findings [25].

The endoscopic images of RAC and intestinal metaplasia were evaluated by three certified endoscopists, and the findings for each patient were based on a consensus of the three endoscopist’s opinions or on the conclusion of discussions among the three endoscopists in cases where there was considerable disagreement.

Clinical outcomes of endoscopic therapy were curative resection rate, procedure duration, complication rate, and rate of noncurative factors [horizontal margin, vertical margin, depth of invasion, lymphovascular invasion, poorly differentiated component in invasive region (GCA only), maximum diameter >30 mm, and presence of ulceration (GCA only)].

Statistical analysis

All P values were obtained using two-sided tests, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Percentages were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Clinical characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. This cohort included 139 patients [120 (86.3%) men and 19 (13.7%) women; 142 lesions] who underwent ESD. Fifty-five lesions were BEA (38.8%) and 87 were GCA (61.2%). All of the lesions could be categorized into BEA and GCA based on pathologic or endoscopic findings. Median age of the patients at ESD was 69.2 ± 9.8 years (BEA 64.1 ± 11.1 years, GCA 71.8 ± 8 years) (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in lifestyle-related background factors between the GCA and BEA groups. The rate of double cancer was not significantly different between GCA and BEA, whereas the rate of metachronous cancer was higher for GCA than for BEA (27 vs. 1.8%, P < 0.01).

Endoscopic findings

Table 2 presents a comparison of endoscopic findings for the two groups (GCA and BEA). Tumor size was significantly greater in the GCA group (P < 0.01). Tumor pathology was differentiated-type adenocarcinoma in 140 lesions (98.5%) and undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma in two lesions (1.5%). With regard to macroscopic type, significantly more tumors were protruding (0-I, 0-IIa) in BEA and depressed (0-IIc) in GCA (P < 0.01). Esophageal hiatal hernia and RAC occurred significantly more frequently in BEA than in GCA (P < 0.01 for both).

On the other hand, intestinal metaplasia occurred significantly more frequently in GCA than in BEA (P < 0.01).

Clinical outcomes of endoscopic therapy

Table 3 shows clinical outcomes of ESD for the GCA and BEA groups. Curative resection rate was significantly higher for GCA (81.6%) than for BEA (61.8%) (P = 0.01). Of the 24 lesions (16.9%) with lymphovascular invasion, a significantly greater number were BEA (P < 0.01). The rate of invasion to the depth of SM2 was significantly greater in BEA (21.8%) than in GCA (8%) (P = 0.02). Median SM invasion depth was 1486 μm in GCA and 935 μm in BEA (P = 0.14).

Additional surgical treatment was undertaken in 26 of the 37 patients (70%) with noncurative resection. There was no lymph node metastasis in either group.

Relationship between depth of invasion and lymphovascular invasion

Table 4 compares the rate of lymphovascular invasion at each invasion depth between groups. Thirty-six patients had noncurative resection of ESD [16 GCA lesions (44.4%) and 20 BEA lesions (55.5%)]. Lymphovascular invasion was identified in four GCA lesions, all of which had submucosal invasion. However, lymphovascular invasion was identified in 14 BEA lesions, of which five had DMM invasion and nine had submucosal invasion.

Discussion

The present study compared background factors and clinical outcomes of ESD in the two types of Siewert type II adenocarcinoma: GCA and BEA. Siewert type II adenocarcinoma is located in the so-called anatomical cardia (true cardia), and cases of it are generally not subdivided into GCA and BEA. However, Nunobe et al. [26] reported clinicopathological and histologic findings for EGJA cases that were divided into 22 GCA cases and 26 BEA cases; this was the only other study aside from the present work to divide cases of Siewert type II adenocarcinoma into GCA and BEA cases. GCA and BEA differ considerably in clinicopathological and histologic findings. The growth of a GCA eventually causes it to extend under the squamous epithelium, which can make it difficult to categorize Siewert type II adenocarcinoma cases into GCA and BEA. However, our data were limited to the submucosa, and there were no cases in which it was difficult to categorize the adenocarcinoma into either GCA or BEA in this study. Compared with GCA, the features of BEA are a younger age, smaller diameter, and a protruding type. Furthermore, both esophageal hiatal hernia and RAC (absence of mucosal atrophy) occurred significantly more frequently in BEA than in GCA. Although there were no significant differences between GCA and BEA in lifestyle-related background factors, the curative resection rate of BEA was lower than that of GCA. Significant factors for noncurative resection were lymphovascular invasion and depth of invasion.

BEA is generally caused by high BMI (especially ≥30 kg/m [2]) in Europe and the United States [13]. However, in the present study, BMI did not differ significantly between the GCA and BEA groups, and was in the normal range for both. According to the OECD Health Data 2015, the frequency of BMI ≥30 kg/m2 in Japan is 3.7%, which is very low compared with the United States [14]. Therefore, the impact of the BMI on BEA is still small in Japan. On the other hand, the frequency of GERD is increasing. Fujiwara et al. reported that the frequency of GERD in patients receiving EGD is increasing greatly [27]. This may be because gastric acid secretion is increasing due to a decrease in H. pylori (HP) infection [28]. Furthermore, Iijima et al. reported that gastric acid secretion in young people who are negative for HP infection is also increasing [29]. Schneider and Corley reported that the continuing decline in HP infection could lead to the disappearance of duodenal ulcers and distal gastric cancers and a marked increase in GERD, Barrett’s esophagus, and BEA [30]. Therefore, increased frequencies of Barrett’s esophagus and BEA may occur with the strong increase in the frequency of GERD in Japan.

In this study, the rate of double cancer was not significantly different in the GCA and BEA groups. In contrast, the rate of metachronous cancer was higher for GCA than for BEA. Kato et al. reported that scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. In this report, the cumulative incidence of metachronous cancers increased linearly and the mean annual incidence rate was 3.5% [31]. Fukase et al. reported that prophylactic eradication of H. pylori after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer prevented the development of metachronous gastric carcinoma [32]. However, the risk of gastric cancer remains at about 3% three years after ESD if HP eradication therapy is successful. Therefore, it is important to perform regular follow-up EGD. On the other hand, the rates of double cancer and metachronous cancer were both low in the BEA group. However, some reports have shown a relationship between BEA and colorectal cancer in Europe [33]. In a meta-analysis by Andrich et al. in which 11 studies (2580 cases of BEA) met the inclusion criteria, a significant positive relationship was observed between BEA and colorectal cancer [34]. BEA was associated with an increased risk of benign adenomatous tumor [odds ratio (OR) 1.69; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.20–2.39], as well as an increased risk of colorectal cancer (OR 1.90; 95% CI 1.35–2.67). Because the incidence of colorectal cancer is projected to increase with the westernization of dietary habits in Japan, it is important to screen for other cancers, especially BEA, if colorectal cancer is detected.

Lymphovascular invasion is predictive of lymph node metastasis in EGJA. In the present study, the rate of lymphovascular invasion in BEA was higher than that in GCA, as noted in a previous report [35], although the median depth of SM invasion was deeper in GCA than in BEA. One possible explanation for this is the differentiation of lymphatic vessel density between the stomach and the esophagus. Brundler et al. found that lymphatic vessel density differed significantly between the stomach and esophagus [36], and we have reported that mucosal lymphatic vessel density is higher in Barrett’s esophagus than in the stomach [37]. Furthermore, in the present study, a large proportion of the BEA lesions demonstrated mucosal lymphovascular invasion. Abraham et al. addressed the significance of tumor invasion into the duplicated MM in Barrett’s esophagus [38]; they evaluated 30 esophagectomy specimens of BEA with invasion into various levels of the duplicated MM. Of the 30 adenocarcinomas, 10 invaded into—but not through—the superficial lamina propria; 12 invaded into the deep lamina propria; and three invaded into—but not through—the DMM. Lymphovascular invasion was identified in five cases (5/30, 17%): one invading the superficial lamina propria (1/10, 10%), two invading the deep lamina propria (2/12, 17%), and two invading the DMM (2/3, 75%). Of these five cases, three were associated with lymph node metastasis. Based on these data, BEA was demonstrated to have pathologic characteristics that were different from those of GCA, and to potentially behave aggressively, even in an intramucosal location.

In the present study, the rate of SM2 invasion was higher for BEA than for GCA. One reason for this was the criterion for SM2 invasion. According to the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, SM2 invasion is >200 μm; however, this is the criterion for esophagus squamous cell carcinoma. On the other hand, the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (JCGC) defines SM2 invasion as >500 μm [15, 16]. In nearly all reports of endoscopic therapy for EGJA, the definition of SM2 has been >500 μm, in accordance with the JCGC. In the present study, if the definition of SM2 had been >500 μm, there would have been no significant difference between the groups [GCA vs. BEA: 7/87 (8.0%) vs. 9/55 (16.3%); P = 0.17]. In Europe, Manner et al. reported efficacy, safety, and long-term results of endoscopic treatment for early-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma SM1 (<500 μm) invasions. They analyzed data from 66 patients with SM1 low-risk lesions (macroscopically polypoid or flat, with a histologic pattern of SM1 invasion; well-to-moderately differentiated; and no invasion into lymph vessels or veins) treated endoscopically. Among the 53 patients who had complete endoluminal remission, lymph node metastasis occurred in only one patient (1.9%; 95% CI 0–4.8) [39].

Furthermore, we have evaluated the frequency of lymph node metastasis and risk factors for lymph node metastasis in 85 surgical specimens of Siewert type I and II lesions (unpublished data) [40]. That study revealed that poor differentiation and lymphovascular invasion were independently associated with risk of nodal disease, but depth of invasion (>500 μm) was not predictive of lymph node metastasis. Of the 18 patients with Siewert type II lesions in which the depth of invasion was within 500 μm, none had lymph node metastasis. While the 5-year survival rate for patients with SM gastric cancer (excluding death caused by other disease) was 96.7% [41], esophagectomy has a mortality rate that is 2–11% higher than that of gastrectomy [42–44]. Therefore, although we think that it may be possible to unify the curative criterion of invasion depth to within 500 µm in ESD for patients with EGJA, it is necessary to determine an appropriate cutoff submucosal invasion depth to perform ESD based on the mortality rate from surgery, the 5-year survival rate, and the frequency of lymph node metastasis.

Limitations of the present study were its small sample size and retrospective nature. There were no cases of lymph node metastasis after additional surgery. Although the rate of noncurative resection of BEA was higher than that of GCA, we were unable to identify a relationship between risk factors for noncurative resection and lymph node metastasis. It will therefore be necessary to evaluate the relationship between risk factors for noncurative ESD and lymph node metastasis in patients who have undergone both endoscopic therapy and surgery.

In conclusion, Siewert type II EGJA comprises two types of cancers with different etiologies. Although there were no significant differences in lifestyle-related background factors, BEA was found to be a risk factor for noncurative resection of ESD in EGJA.

References

Center for Cancer Control and Information Services. Cancer statistics in Japan ’14 (last update 21 May 2015). Tokyo: National Cancer Center. http://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/brochure/backnumber/2014_jp.html. Accessed 3 Jan 2016.

Kusano C, Gotoda T, Khor CJ, et al. Changing trends in the proportion of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in a large tertiary referral center in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1662–5.

Drahos J, Xiao Q, Risch HA, et al. Age-specific risk factor profiles of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(1):55–64.

Xie FJ, Zhang YP, Zheng QQ, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and esophageal cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(36):6098–107.

Shimoda T. Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, the 10th edition—pathological part (in Japanese). Nihon Rinsho. 2011;69(Suppl 6):109–20.

Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1457–9.

Hongo M. Review article: Barrett’s oesophagus and carcinoma in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 8):50–4.

Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(6):1825–31.

Chang CY, Cook MB, Lee YC, et al. Current status of Barrett’s esophagus research in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(2):240–6.

Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–9.

D’Elia L, Galletti F, Strazzullo P. Dietary salt intake and risk of gastric cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;159:83–95.

Peleteiro B, Castro C, Morais S, Ferro A, Lunet N. Erratum to: Worldwide burden of gastric cancer attributable to tobacco smoking in 2012 and predictions for 2020. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2851.

Thrift AP, Shaheen NJ, Gammon MD et al. Obesity and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus: a Mendelian randomization study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11). doi:10.1093/jnci/dju252.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD health statistics 2015. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm. Accessed 3 Jan 2016.

Association Japanese Gastric Cancer. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–23.

Fujita H, Tsubuku T, Tanaka T, Tanaka Y, Matono S, Shirouzu K. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer: clinical efficacy and impact (in Japanese). Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;108:246–52.

Park CH, Kim EH, Kim HY, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early stage esophagogastric junction cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47(1):37–44.

Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C and M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392–9.

Chandrasoma P, Makarewicz K, Wickramasinghe K, Ma Y, Demeester T. A proposal for a new validated histological definition of the gastroesophageal junction. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:40–7.

Hoshihara Y, Kogure T. What are longitudinal vessels? Endoscopic observation and clinical significance of longitudinal vessels in the lower esophagus. Esophagus. 2006;3:145–50.

Kusano C, Kaltenbach T, Shimazu T, et al. Can Western endoscopists identify the end of the lower esophageal palisade vessels as a landmark of esophagogastric junction? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:842–6.

Nakajima T, Oda I, Gotoda T, et al. Metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection: how effective is annual endoscopic surveillance? Gastric Cancer. 2006;9(2):93–8.

Yagi K, Honda H, Yang JM, et al. Magnifying endoscopy in gastritis of the corpus. Endoscopy. 2005;37(7):660–6.

Uedo N, Ishihara R, Iishi H, et al. A new method of diagnosing gastric intestinal metaplasia: narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38(8):819–24.

Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, et al. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(10):1161–81.

Nunobe S, Nakanishi Y, Taniguchi H, et al. Two distinct pathways of tumorigenesis of adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction, related or unrelated to intestinal metaplasia. Pathol Int. 2007;57(6):315–21.

Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:518–34.

Iijima K, Koike T, Abe Y, et al. Time series analysis of gastric acid secretion over a 20-year period in normal Japanese men. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(8):853–61.

Iijima K, Koike T, Abe Y, et al. A chronological increase in gastric acid secretion from 1995 to 2014 in young Japanese healthy volunteers under the age of 40 years old. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016;239(3):237–241.

Schneider JL, Corley DA. A review of the epidemiology of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29:29–39.

Kato M, Nishida T, Yamamoto K, et al. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013;62(10):1425–32.

Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–7.

Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Barrett’s metaplasia and colonic neoplasms: a significant association in a 203,534-patient study. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2046–51.

Andrici J, Tio M, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Meta-analysis: Barrett’s oesophagus and the risk of colonic tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:401–10.

Iizuka Shu Hoteya Akira Matsui Toshiro, et al. Comparison of the clinicopathological characteristics and results of endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophagogastric junction and non-junctional cancers. Digestion. 2013;87:29–33.

Brundler MA, Harrison JA, de Saussure B, de Perrot M, Pepper MS. Lymphatic vessel density in the neoplastic progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:191–5.

Omae M, Fujisaki J, Tomoki S, et al. The lymph vascular density in the area of esophagogastric junction (in Japanese). Paper presented at 89th Congress of Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES); Aichi, Japan; 2015 May 29–31.

Abraham SC, Krasinskas AM, Correa AM, et al. Duplication of the muscularis mucosae in Barrett esophagus: an underrecognized feature and its implication for staging of adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1719–25.

Manner H, Pech O, Heldmann Y, et al. Efficacy, safety, and long-term results of endoscopic treatment for early stage adenocarcinoma of the esophagus with low-risk sm1 invasion. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:630–5.

Osumi H, Fujisaki J, Omae M, et al. Risk of lymph node metastasis in surgically resected Siewert type I and type II T1 adenocarcinomas (P-146). Presented at 70th Annual Meeting of the Japan Esophageal Society; Tokyo; 2016 4–6 July.

Sasako M, Kinoshita T, Maruyama K. The prognosis of early gastric cancer (in Japanese). Stomach Intestine. 1983;28:139–46.

Siewert JR, Feith M, Werner M, Stein HJ. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: results of surgical therapy based on anatomical/topographic classification in 1002 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232:353–61.

Lee L, Ronellenfitsch U, Hofstetter WL, et al. Predicting lymph node metastases in early esophageal adenocarcinoma using a simple scoring system. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:191–9.

Yamashita H, Katai H, Morita S, Saka M, Taniguchi H, Fukagawa T. Optimal extent of lymph node dissection for Siewert type II esophagogastric junction carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2011;254:274–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

The present study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by our institutional review board (Registry No. 2015-1159), and involved human participants. We obtained comprehensive written informed consent for the study before ESD was performed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osumi, H., Fujisaki, J., Omae, M. et al. Clinicopathological features of Siewert type II adenocarcinoma: comparison of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma following endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer 20, 663–670 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-016-0653-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-016-0653-x