Abstract

Current models of sexual responding emphasize the role of contextual and relational factors in shaping sexual behavior. The present study used a prospective diary design to examine the temporal sequence and variability of the link between sexual and relationship variables in a sample of couples. Studying sexual responding in the everyday context of the relationship is necessary to get research more aligned with the complex reality of having sex in a relationship, thereby increasing ecological validity and taking into account the dyadic interplay between partners. Over the course of 21 days, 66 couples reported every day on their sexual desire, sexual activity (every morning), and relationship quality (every evening). In addition, we examined whether the link between these daily variables was moderated by relationship duration, having children, general relationship satisfaction, and sexual functioning. Results showed that the sexual responses of women depended on the relationship context, mainly when having children and being in a longer relationship. Male sexual responding depended less on contextual factors but did vary by level of sexual functioning. Several cross-partner effects were found as well. These results verify that relational and sexual variables feed forward into each other, indicating the need to incorporate interpersonal dynamics into current models of sexual responding and to take into account variability and dyadic influences between partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the years, several models have been forwarded to describe the sexual response of men and women.Footnote 1 Whereas the traditional sexual response cycle defines sexual responding as a linear sequence of desire, arousal, and orgasm, recent models put more emphasis on intimacy and relationship features in determining sexual behavior. Given the amount of research that links relationship processes to sexual experiences and the fact that even the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) takes relationship factors into consideration when diagnosing a sexual disorder, it can be argued that any valid model on sexual responding should ascribe a prominent role to interpersonal dynamics. This would be particularly the case when defining female sexuality because the latter is generally described as more context-dependent than male sexuality which is grounded more in physical aspects and guided by internal sensory cues (Baumeister, 2000). Nevertheless, the interpersonal perspective on sexuality still lacks theoretical and empirical embedding. To shed further light on the role of relationship factors in generating and regulating sexual behavior, more systematic research is needed. The present study aimed to fill this gap by disentangling the interrelation between sex and relationships in a daily context using a diary design in a sample of couples.

Conceptual Evolution: The Interplay Between Sex and Relationships

Whether or not relational factors are central to sexual desire and whether this is different for men and women has been widely discussed in theoretical and empirical papers. When explaining human sexuality, many researchers adhere to the original model of Masters and Johnson (1966) which (1) defines sexual desire as a spontaneous, almost instinctive drive to engage in sexual activity; (2) focuses on genital responses as an indicator of sexual desire and arousal; and (3) considers sexual gratification and orgasmic release as the primary outcome of sexual responding (Hayes, 2011; Meana, 2010). Essentially, the traditional model of sexual responding does not differentiate between men and women and does not take into account contextual and relational factors as potential generators, regulators, and outcomes of sexual responding. In recent years, theories about human sexuality have evolved in their relative emphasis on physical responses versus more subjective and relational contributions (Baumeister, 2000). Being one of the first to address the importance of relationship variables, particularly in women, Basson (2000) forwarded a new model on the female sexual response that (1) assumes overlapping phases of sexual desire and arousal in a variable temporal sequence; (2) emphasizes the responsive component of sexual desire, which means that sexual desire does not arise from a biological urge but is more often triggered by relational motives and intimacy needs; and (3) considers non-sexual benefits of sexual activity such as intimacy, commitment, and feeling sexually desirable.

Although this revised model became highly influential in describing women’s sexuality, it did raise critical questioning as well because it offers a restrictive view on female sexual desire. Endorsing the latter as a relationally determined response is not reflective of all women’s sexual experiences but would apply mainly to women with sexual dysfunctions and women in longer committed relationships (Giles & McCabe, 2009; Meana, 2010; Sand & Fisher, 2007). In support of this, there is evidence showing that a model based on spontaneous sexual desire represents the female sexual response equally well as a model that draws a direct path between emotional closeness and sexual desire (Giles & McCabe, 2009). Also, the idea that male sexual responding operates independently from relational variables may be contested, especially in the context of long-term relationships (Giraldi, Kristensen, & Sand, 2015).

The fact that no conclusive evidence has been found yet on the exact link between relational factors, sexual desire, and sexual activity suggests that variability exists in sexual responding, both within and across genders. This indicates the need to further examine whether and how sexual and relational variables feed forward into each other and whether this dynamical sequence will vary as a function of gender or other relevant variables. Given that sex deepens the relational bond and contributes to feelings of closeness and relationship satisfaction (Debrot, Meuwly, Muise, Impett, & Schoebi, 2017; Sprecher & Cate, 2004), it can be assumed that positive rewards derived from previous sexual activities (e.g., emotional closeness) fuel the motivation and desire for sexual activities in the future. From another point of view, it can also be assumed that not relational factors but sexual activity in itself triggers responsive desire, which facilitates further sexual responding and desire.

Variability in Sexual Responding

In addition to studying gender differences in the association between sexual behavior and relational factors, it is also relevant to consider the moderating influence of personal and relationship characteristics that have been theoretically linked to responsive desire, namely relationship duration, having children, level of sexual functioning, and overall relationship satisfaction (Basson, 2000; Hayes, 2011). Although sexual frequency tends to drop with relationship duration, it has been suggested that intimacy and closeness become increasingly important to sexual desire over the course of a relationship, and this is probably the case for both men and women (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Hinchliff & Gott, 2004; Liu, 2003). Research has indeed shown that both men and women’s sexual pleasure is associated with relationship status and relationship duration (Carpenter, Nathanson, & Kim, 2009) and is driven by love and commitment motives (Meston & Buss, 2007). In a related vein, it is plausible to assume that having children will influence the association between relational intimacy, sexual desire, and sexual activity. It has been found that parenthood lowers sexual interest and sexual frequency (Call, Sprecher, & Schwartz, 1995; Liu, 2000; Schröder & Schmiedeberg, 2015). Another relational variable that may be particularly relevant when examining sexual responding is relationship satisfaction. Several studies have demonstrated that feeling satisfied with the relationship transfers to the sexual lives of partners, thereby influencing the determinants, quality, and quantity of sexual activity (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000). Furthermore, there is recent evidence showing that the link between sexual and relationship satisfaction is bidirectional (McNulty, Wenner, & Fisher, 2016). Finally, level of sexual functioning is assumed to play a major role in determining the sequence of sexual responding. It has been argued that Basson’s conditional type of responsive desire would fit mainly women with sexual problems (Sand & Fisher, 2007).

The Present Study

The present study adds to this line of research, providing further empirical evidence on the link between relational factors, sexual desire, and sexual activity. Most studies so far have relied on cross-sectional, retrospective designs that measure sexual responses at one single time, which does not allow investigating temporal relations between variables. Therefore, the present study used a daily diary methodology to examine prospective relations between the relational context, sexual desire, and sexual activity in a couple’s daily life. Because diaries are able to capture detailed experiences in natural contexts near the time of occurrence (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003; Laurenceau, Feldman Barrett, & Rovine, 2005), such a design is better suited to prospectively monitor the interrelations between the different components of the sexual response and increases the ecological validity of sex research. Another important concern about previous work on sexual responding is its almost exclusive focus on measuring individual responses. Given that relational intimacy would be an important motive in (women’s) sexuality and given that sexuality itself often takes place in the context of a relationship (Dewitte, 2014), research on sexual responding needs to include the dynamic interplay between both partners’ responses. Finally, previous work is often complicated by its reliance on selected samples and does not control for potential moderating influences other than sexual dysfunction.

To address the aforementioned issues, we administered a daily diary in a sample of couples and tested pathways between relationship quality, sexual desire, and sexual activity on a daily level. This study design allowed a more detailed view on the temporal sequence and variability in sexual responding and considered the moderating influence of contextual and relational variables. More concretely, we tested (1) whether the quality of the relationship on a given day determined sexual desire and sexual activity, eventually leading to an increase in relationship quality the following day or (2) whether sexual desire independently feeds forward into sexual activity, which, in its turn, increases the experience of sexual desire and the odds of having sex the following day, and (3) whether the pattern of relationship quality, sexual desire, and sexual activity differs as a function of relationship length, having children, overall relationship satisfaction, and sexual functioning. By including both couple members, this is the first study testing the relational nature of sexual responding using a dyadic approach. We focused only on heterosexual couples because this allowed testing both dyadic influences and potential gender differences in the pathways between sexual and relationship responses.

Hypotheses

First, we tested a basic model, exploring whether sexual activity on a given day depends on either the quality of the relationship or on the level of sexual desire that day and whether relationship and sexual variables have an effect on the (sexual) relationship the following day. Aligning with the dominant narrative on male and female sexuality, we expected that sexual responses in women would be determined more by relationship factors, whereas men’s sexuality would depend more on their level of sexual desire rather than relationship quality. Regarding moderating factors, we expected that sexual desire and sexual activity would predict and be predicted by daily relationship quality rather than by sexual responding itself (1) in longer relationships, (2) when having children, (3) when feeling less satisfied with the relationship in general, and (4) when reporting lower levels of sexual function.

Method

Participants

A total of 66 heterosexual couples participated in this diary study in return for a monetary award (30 euros). The couples were contacted via social media and by word of mouth and asked to provide diary reports twice a day over the course of 21 consecutive days. Of all couples who were contacted, about 22% refused to participate, mainly because of time constraints or privacy issues (i.e., not wanting to report on intimate topics such as sexual behavior). Potential study participants were included if they (1) were at least 18 years, (2) were in a steady monogamous relationship of at least 1 year, and (3) lived together. The average relationship length of the couples was 9.2 years (range 1–45 years with 50% of the couples having a relationship of less than 4 years). A total of 28.8% of the couples were married and 47% had children; 36% of the participants were students, 39% were employees, 8% were laborers, 13% owned their own business, and 4% were unemployed. Women ranged in age from 19 to 65 years (M = 28.41, SD = 10.56) and men ranged in age from 21 to 65 years (M = 30.90, SD = 10.39), with 75% of the men and women being younger than 35 years.

Procedure

Participants were recruited by means of flyers that were distributed at the university and local grocery shops. The flyers advertised about a study on sex and relationships for which steady couples were needed. Eligible couples who had shown interest in the study were contacted by phone to explain the protocol and run through the diary items in order to ensure a good understanding of all questions. All data were collected via an Internet-based system. Participants were instructed to complete the electronic diary independently and to refrain from discussing responses with their partner until completion of the study. Upon agreement, they were sent an individual code with which they could log into the online system. First, participants completed a set of electronic questionnaires, including one on demographics. From then on, participants reported, each evening for 3 weeks, on their level of relationship quality experienced during that day.Footnote 2 They had a time window from 8 p.m. to 3 a.m. to complete the evening diary. Each morning, they reported on their sexual desire and sexual activity since the last time they completed their morning diary (i.e., sexual behavior of the past 24 h). They had a time window from 7 a.m. to 12 p.m. to complete the morning diary. Given that most sexual interactions between partners are likely to occur after retiring to bed and before arising (Burleson, Threvathan, & Todd, 2007), we asked participants to report on relational experiences in the evening and sexuality in the morning. This design enabled us to test both directions of the temporal relationship between sexuality and relationship quality. On the one hand, we tested whether relationship feelings during the day would predict the occurrence of sexual activity on the same day and, on the other hand, we tested whether those sexual acts have enduring effects on the relationship, thereby predicting relationship feelings on a following day. Electronic time and date stamps were used to monitor and verify compliance with daily questionnaire completion. To improve compliance with the diary protocol, participants received a text message every evening at 21 h and every morning at 7 h 30 to remind them of their diary. The overall completion rate of the diaries was fairly high, yielding only 6.33% of missing data. This study was approved by the Ethical Board of Ghent University.

Measures

To measure relationship quality on a daily level, participants reported on a 7-point scale ranging from not at all to very much, to what extent (1) they felt satisfied with their relationship that day, (2) how much closeness they experienced in their relationship that day, (3) and how much commitment toward their partner they felt that day. These items were sampled from previous diary studies on relationship experiences (Gable, Reis, & Downey, 2003; Laurenceau, Feldman Barrett, & Rovine, 2005; Tidwell, Reis, & Shaver, 1996). We averaged the three highly correlated (.68–.74) items and calculated a mean relationship quality score. This multi-item scale showed good reliability α = .79. The scores ranged from 1 to 7 and the mean daily relationship quality score was 5.39 for men and 5.26 for women.

Participants also reported on a 7-point scale, ranging from not at all to very much, the extent to which they experienced sexual desire since the last time they completed their morning diary. Based on previous conceptual and empirical work (e.g., Baumeister, 2000; Spector, Carey, & Steinberg, 1986), we defined sexual desire as “thinking and fantasizing about sex as well as wanting to engage in sexual activity with their partner.” Applying a broad definition of sexual desire reduces the risk of getting locked in a methodological loop that would inflate the link between sexual desire and sexual activity. The scores ranged from 1 to 7 and the mean daily sexual desire score was 3.35 for men and 2.48 for women. Participants also reported whether or not sexual activity with their partner had occurred (yes/no). Sexual activity was defined as “oral sex, genital touching, and vaginal/anal penetration with their partner.” When reporting whether sexual activity had occurred that day, participants also had to indicate when they had have sex with their partner. In almost all cases, sex occurred in the evening, night, or in the morning. The number of reported sexual activities during the 21-day study period ranged from 0 to 14 times (M = 6.98, SD = 3.01). The three couples who reported no dyadic sex during the study period were not taken into account for the analyses on sexual activity and sexual function. Overall, couple members agreed about having had sex in 98.97% of the cases.

Participants provided demographic information on age, profession, relationship duration, relationship status, and having children or not.

General relationship satisfaction was measured using a Dutch and shortened version of the Maudsley Marital Questionnaire, containing 17 statements to which participants responded on 9-point Likert scales. Items scores were summed and ranged from 0 to 153. Higher scores indicate greater relationship dissatisfaction. The MMQ scale has good psychometric properties (Arrindell, Boelens, & Lambert, 1983; Orathinkal, Van Steenwegen, & Stroobants, 2007). In the current sample, internal consistency was good (α = .75). The scores ranged from 0 to 36 (M = 10.89, SD = 8.17) in men and from 0 to 38 (M = 11.92, SD = 9.47) in women, indicating relatively high satisfaction scores in both couple members.

To measure the sexual functioning of women, we administered the Female Sexual Function index (FSFI; Rosen et al., 2000), which is a 19-items questionnaire using 6-point Likert scales to measure sexual functioning on the dimensions of sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. In the present study, we used only the total score, with higher scores indicative of better sexual functioning. Scores can range from 2 to 36. The Dutch version of the questionnaire has sound psychometric properties (ter Kuile, Brauer, & Laan, 2006). In the present sample, high internal consistency was demonstrated, α = .78 to .84. The scores of the women ranged from 4.50 to 33.30 with a mean score of 28.15 (SD = 4.60).

Sexual functioning of men was measured using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF; Rosen et al., 1997), which is a 15-items measure that covers five domains: erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction. Items were scored on 6-point Likert scales, with higher scores indicative of better sexual functioning. Only the total score was used in the present study. Scores can range from 0 to 75. The IIEF has been found to demonstrate high reliability and validity. In the present sample, internal consistency scores were good, α = .72 to .86. The scores of the men ranged from 48 to 74 with a mean of 66.06 (SD = 5.58).

For both relationship satisfaction and sexual functioning, participants were instructed to report on their situation of the past 4 weeks.

Statistical Analyses

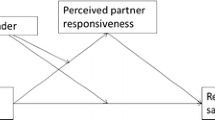

In order to model the dynamic interplay between couples, we used a structural equation modeling approach for longitudinal data (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013; Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Our basic model included the regressions of all outcome variables of interest (male and female sexual desire, male and female relationship quality, and an indicator whether the couple had sex) on the corresponding variables measured at the previous occasion. The couple was the main unit of analysis, with male and female responses nested within the couple. To examine the main study questions, we relied on the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) which provides a simultaneous test of actor and partner main effects (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). All predictor variables had to be lagged because the questions on sexual desire and sexual activity were completed in the morning and were thus coded as the following day, while relationship quality of that day was coded as the previous day. This implies that the temporal association between desire and sex was defined as a Lag 1 effect, whereas the temporal associations including relationship quality were defined as Lag 2 effects. To ensure a correct understanding of our results, we simplified the description of the effects such that t1 refer to scores on relationship quality, desire, and sexual activity on a previous day. Figure 1 shows a path diagram of our final model, illustrating the effects of our basic model. Variables were grand-means centered, thereby assuming that the within-person effects were the same as the between-person effects. We used a logistic regression for the submodel with sexual activity as the dependent variable. All regressions were estimated simultaneously using robust maximum likelihood with corrected standard errors (SE) for clustered observations in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). In a second step, we extended our basic model to investigate whether the effects changed depending on potential moderators, namely relationship duration, having children, sexual functioning, and overall relationship satisfaction. We investigated the role of each of the potential moderators by fitting a separate model, where we included the potential moderator along with interaction terms of the potential moderator with all predictor variables.

Path diagram presenting the main effects of relationship satisfaction, sexual desire, and sexual activity of the basic model. Note: Because this is a conceptual diagram, we did not include residual variances. Only significant paths are shown, but all have been included in the statistical model. For ease of interpretation, we have labeled the lagged previous-day effects as t − 1 (i.e., t1 in the text), whereas next-day effects were labeled as t + 1. The lag + 1 coefficients are not shown on the right-hand side because they are identical to the lag − 1 coefficients on the left-hand side of the figure

Results

Basic Model

Analyses showed that men’s appraisal of relationship quality on a given day was predicted by their own and their partner’s level of relationship quality on the previous day (see Table 1 for an overview of the coefficients and SE). Male sexual desire was predicted by their own level of sexual desire and the occurrence of sexual activity on a previous day. In case of the latter, it was found that having sex on a given day decreased their sexual desire the next day.

In women, we found that daily relationship quality was predicted by their own rating of relationship quality on a previous day. Sexual desire was predicted by their own and their partner’s level of desire, their own level of relationship quality, and the occurrence of sexual activity on a previous day. Similar to men, we found that the occurrence of sex on a given day decreased female sexual desire on the following day. The occurrence of sexual activity was predicted only by women’s daily relationship quality of the previous day.

Directly comparing male and female effects in our basic model, we tested for gender differences in the observed effects. We found that the effect of relationship quality on sex was different for males and females (difference of regression coefficients: − .32, SE = .14, p = .02), which fits with the hypothesis that relationship factors are more important to female than male sexuality. We also found that female relationship quality significantly predicted male relationship quality but not vice versa. However, the difference in regression coefficients was not significant (difference: − .07, SE = .08, p = .36). Male desire significantly predicted female desire but not vice versa. Again, the difference in regression coefficients was not significant (difference: .02, SE = .05, p = .71). For females, relationship quality predicted desire, whereas for males, relationship quality did not predict desire and the difference in regression coefficients was significant (difference: − .14, SE = .07, p = .03). This fits with our hypothesis that female sexual desire is more dependent on relationship quality than male sexual desire.

Moderation Effects

Relationship Duration

Relationship duration moderated the effect of female relationship quality on sexual activity the following day, Coef. = .03 (SE = .01), p = .01, and the effect of sexual activity on female relationship quality the following day, Coef. = .03 (SE = .01), p = .01. Concretely, it was found that the effect of daily relationship quality on the occurrence of sexual activity the following day was stronger in longer than in shorter relationships. In the same vein, we found that the positive effect of sexual activity on female relationship quality the following day increased with longer relationship duration. None of the other moderation effects were significant, all Coef.’s < .01. This pattern of results fits with our hypothesis that the association between relationship factors and sexual responses is stronger in longer relationships.

Presence of Children

Having children had a negative effect on daily relationship quality in women, Coef. = − 1.16 (SE = .55), p = .03. The presence of children also moderated the effect of female relationship quality, Coef. = .51 (SE = .18), p = .01, and female sexual desire on sexual activity the following day, Coef. = − .33 (SE = .16), p = .04. Examining the direction of the interaction revealed that the presence of children further strengthened the negative effect of female desire on sexual activity the following day, while having no children decreased the negative effect of desire on sexual activity the following day. In addition, the presence of children increased the positive effect of daily relationship quality on sexual activity. This result confirms our hypothesis that sexual responses are more dependent on relationship processes when having children. None of the other moderation effects were significant, all Coef.’s < .14.

Overall Relationship Satisfaction

Regarding the effects of overall relationship satisfaction, we found that relationship satisfaction in women had a positive effect on their daily sexual desire, Coef. = .05 (SE = .02), p = .01, and on sexual activity, Coef. = .12 (SE = .02), p = .04, which fits with our hypothesis. We also found that relationship satisfaction in men moderated the effect of daily relationship quality in women on sexual activity the following day, Coef. = .03 (SE = .01), p = .01. Examining the direction of this interaction revealed that the less satisfied their partner felt with the relationship, the more positive the effect was of daily relationship quality on the odds of having sex the following day. Relationship satisfaction in women, on the other hand, moderated the effect of sexual activity on daily relationship quality in women, Coef. = − .02 (SE = .01), p = .05, indicating that the less satisfied women felt with the relationship, the stronger the effect was of sexual activity on their daily reports of relationship quality the following day. Finally, relationship satisfaction in women moderated the effect of previous-day sexual activity on the occurrence of sexual activity the following day, Coef. = .04 (SE = .02), p = .04, indicating that the more satisfied women were with their relationship, the less negative the effect was of previous-day sexual activity on sexual activity the following day. These results correspond with our hypothesis that sexual responses depend more strongly on relationship quality when, overall, feeling less satisfied with the relationship. None of the other moderation effects were significant, all Coef.’s < .01.

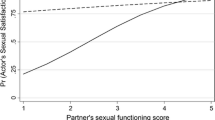

Sexual Functioning

Sexual functioning of both men and women had a positive effect on sexual activity, indicating that the odds of having sex increased when men and women scored higher on sexual function, Coef. = .31 (SE = .13), p = .01 in men and Coef. = .38 (SE = .16), p = .02 in women. Several moderating effects also reached significance. Sexual functioning in men moderated the effect of female desire on female relationship quality the following day, Coef. = − .02 (SE = .01), p = .02; the effect of male and female sexual desire on sexual activity the following day, Coef. = .04 (SE = .02), p = .02 in men and Coef. = − .05 (SE = .01), p = .01 in women; and the effect of sexual activity on female desire the following day, Coef. = .04 (SE = .02), p = .03. Examining the direction of the interaction terms revealed that the effect of female desire on their level of relationship quality the following day became less negative when their partner reported lower levels of sexual functioning. In addition, the effect of sexual activity on next-day female desire became less negative when the partner scored higher on sexual function. Finally, sexual desire in men had a stronger effect on sexual activity the following day when men reported higher sexual function, whereas the negative effect of female desire on sexual activity decreased with lower levels of sexual function in men. This pattern of results did not correspond well with our hypothesis that the link between relationship factors and sexual responding would be stronger in case of lower sexual functioning. None of the other moderation effects were significant, all Coef.’s < .01.

Sexual functioning in women had a negative main effect on sexual desire in men, Coef. = − .13 (SE = .06), p = .04. Female sexual functioning also moderated the effect of female sexual desire on male relationship quality the following day, Coef. = − .01 (SE = .01), p = .05, and the effect of male desire on sexual activity the following day, Coef. = − .05 (SE = .02), p = .02. The lower the level of sexual function in women, the more positive the effect was of female sexual desire on men’s daily rating of relationship quality the following day. We also found that the less sexual function women reported, the more positive the effect was of male sexual desire on sexual activity the following day. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find evidence that sexual responding would depend more strongly on relationship processes when women report lower sexual function. None of the other moderation effects were significant, all Coef.’s < .01.

Discussion

The present study examined temporal associations between relationship quality, sexual desire, and sexual activity in the everyday context of the relationship, taking into account the dyadic interplay between partners and the moderating influence of contextual and relational variables. Using a dyadic daily diary method, we prospectively monitored how relational and sexual variables feed forward into each other, thereby adding to the current literature on the role of relationship factors in sexual responding.

Basic Model: Daily Relationship Quality, Sexual Desire, and Sexual Activity

Examining the interrelations between daily relationship quality, sexual desire, and sexual activity, we found that the sexual desire of women depended on how much satisfaction, closeness, and commitment she experienced toward her partner during the day and on a previous day. In addition to relationship quality, women’s desire also depended on the level of desire she and her partner experienced the day before, which fits with current descriptions of female sexual desire as highly conditional on relationship and partner-related dynamics (Basson, 2000, 2005, 2015). In the same vein, we found that the odds of having sex increased when women felt more satisfied with their relationship on a previous day. Such intimacy-based sexual responding is a key feature of Basson’s (2000, 2005) revised model, indicating that woman’s motivation to engage in sex does not necessarily arise from intra-individual desires, but is more likely determined by relational factors and situational events. Note that the direct path going from sexual desire to sexual activity was not significant. These results confirm that signs of rising intimacy will get women in the mood to initiate or consent with sexual acts, indicating the need to incorporate emotional intimacy and relationship quality in models of female sexual responding. Male sexual responding, on the other hand, did not depend on contextual factors, which fits with the traditional script of male sexuality (Masters & Johnson, 1966). In support of this, several studies have shown that men are more susceptible to internal rather than contextual features of sex and report more physical and less emotional reasons for engaging in sex with their partner (Birnbaum & Laser-Brandt, 2002; Klusmann, 2002).

Moderation Model: The Role of the (Relational) Context

In general, we found that contextual variables (i.e., relationship duration, satisfaction and children) moderated the link between sex and relationship variables in women, but not in men. This fits with the idea that female sexuality is more responsive to person by situation interactions and thus more variable than men’s sexual experiences (Baumeister, 2000; Regan & Berscheid, 1995).

Relationship Duration

Our results showed that the link between daily relationship quality and sexual responses did not uniformly apply to all women. When being in a longer relationship, we found that higher levels of relationship quality during the day encourage future sex, which then further increases the level of satisfaction women experience in their relationship on the following day. The fact that positive relationship interactions anchor the sexual experience in longer relationships points toward the regulatory function of sex for maintaining and promoting a qualitative relationship. Corroborating with our results, there is increasing evidence suggesting that responsive desire is more prominent in particular stages of a woman’s life and that factors motivating intimate contact within a couple may change over the course of a relationship (Beck, Bozman, & Qualtrough, 1991; Carpenter, Nathanson, & Kim, 2009; Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Liu, 2003). Research has shown a decline in sexual desire in women with length of relationship but an increase in the desire for tenderness (Klusmann, 2002; Meston & Buss, 2007).

The Presence of Children

Having children strengthened the association between sexual activity and women’s daily evaluation of their relationship. From an evolutionary perspective, intimacy needs may become increasingly important in women with children because displays of commitment between partners serve to preserve, guard, and reinforce the well-being of the family, thereby improving the chances of reproductive success (Buss, 2003). Clinical observations have taught us that the presence of children inclines women to ignore or disregard their own sexual arousal because their primary focus is on keeping the relationship and the household going (Call et al., 1995; Liu, 2000). Having children also seemed to decrease women’s daily appraisals of relationship quality. It is plausible that, when evaluating the relationship as more satisfying than usual, women are more motivated to engage in sexuality in order to deepen the emotional bond and boost feelings of (sexual) attractiveness (Debrot et al., 2017; Schröder & Schmiedeberg, 2015). Interestingly, the negative effect of sexual desire on sexual activity decreased when having no children, suggesting that the absence of children increases the opportunity for women to attend to and act on their feelings of sexual desire.

Relationship Satisfaction

Our results showed that women and men who are generally less satisfied with their relationship benefit from sexual activity, as the link between daily relationship quality in women and sexual activity became stronger with lower levels of satisfaction. This suggests that sex may serve to restore the relational context. The fact that the occurrence of sexual activity depended primarily on how women felt about the relationship points toward the pervasiveness of women’s (daily and general) satisfaction in determining the antagonists, motivators, and gains of sexual activity. This fits with the general description of women taking a leading responsibility in the relationship and being more prone to fuse sex and love (Diamond, 2003; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001).

Sexual Function

Level of sexual function had several moderating effects on the link between daily relationship quality, sexual desire, and sexual activity in both men and women. First, male sexual desire increased the odds of having sex on a following day when reporting higher sexual function. This fits with common descriptions of the “normal” male response in which sexual activity was initiated by internal signs of sexual desire (Masters & Johnson, 1966). The link between male sexual desire and sexual activity also depended on their female partner’s level of sexual function. Interestingly, the same dynamic occurred in women. That is, the extent to which female sexual desire during the day develops into concrete sexual acts was moderated by the male partner’s level of sexual function. In both cases, the link between sexual desire and sexual activity became stronger with lower levels of sexual function in the partner. These cross-partner effects suggest that the sexual response of the partner with better sexual function is most important in determining whether sex will occur or not. In view of relationship dynamics, this may indicate that the partner with lower sexual function will consent with sexual activity to keep the relationship going (Elmerstig, Wijma, & Berterö, 2008).

When elaborating on the link between sexual desire and sexual activity, the inclusion of moderator variables may help us to understand why sexual desire and sexual activity shared no direct path. Based on theoretical and empirical findings, we expected that sexual activity would be fueled by feelings of sexual desire. Our results showed that sexual desire during the day did indeed lead to concrete physical acts, but this depended on level of sexual functioning. That is, the negative effect of female desire on the occurrence of sexual activity decreased with lower levels of sexual functioning in men and the positive effect of male desire on sex increased with lower levels of sexual functioning in women. Given that sexual dysfunctions in one partner inevitably affect the other partner and that sexual problems in a relationship often go along with a lower sexual frequency and lower sex drive (Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999; Levine, 2003), it could be that men and women with lower sexual function will more easily act on their sexual urges whenever they do occur, whereas people with better sexual function may feel less driven to express their sexual desire every time they desire or fantasize about sex. In support of this, the literature on human motivation indicates that blocked goals become more salient, thereby increasing initial responses, effort, and persistence to reach the goal (Klinger, 1975). In this respect, it is worth noting that, regardless of (relational) context and sexual function, the occurrence of sexual activity decreased next-day feelings of desire in both men and women. It is plausible that the sexual gratification derived from sexual activity lingers on the following days and will boost the desire for sex on future occasions, but not necessarily on the next day.

When considering the moderating impact of sexual function on the link between relationship quality and sexual activity, we did not find support for the idea that women’s relational motivation to engage in sex is more characteristic of women with lower sexual function (Giles & McCabe, 2009; Giraldi, Kristensen, & Sand, 2015; Sand & Fisher, 2007). Previous work has suggested that (particularly) women who gain less physical pleasure from sex are more motivated to have sex for its non-sexual benefits such as intimacy and self-concept related goals (Basson, 2005; Sand & Fisher, 2007). Accordingly, we expected a link between daily relationship quality and sexual activity instead of the observed link between desire and sex. On the other hand, our results did reveal that sexual function moderated the link between sexual desire and daily relationship quality. That is, when both men and women reported less sexual function, higher levels of female desire during the day increased how they and their partner evaluated their relationship on the following day. It could be that couples facing sexual difficulties will interpret feelings of sexual desire as a sign of improved sexual functioning, which feeds forward into the relationship and increases partner’s feelings of closeness and commitment toward each other. Given that women are generally characterized by lower sexual desire and thereby determine the frequency and pacing of sexual activity (Peplau, 2003; Petersen & Hyde, 2010), it makes sense that female desire is most influential in gaining satisfaction from sexual responding.

Limitations

Although the present findings are novel and promising, some limitations remain. Most importantly, our sample included relatively young, relationally satisfied, and sexually healthy partners who were open to report on sexual issues. Our results may therefore not generalize to the broader population nor may they characterize the sexual dynamics of sexually and relationally distressed couples. The latter is especially important when interpreting the results on the moderating role of relationship satisfaction and sexual function. In the same vein, our sample did not show a balanced distribution of relationship duration or having children, which limits the interpretation of their moderating influence. In addition, we included only a limited amount of daily variables. It is beyond doubt that many other variables are also worth investigating in future diary studies. For example, measuring who initiated the sexual activity and recording whether and why a desire to initiate sex did not result into concrete actions might further our understanding of the link between sexual desire and sexual activity. We had, however, good reasons to focus only on these variables because we were primarily interested in the impact of contextual variables on sexual responses and strived toward parsimony in modeling their interrelations. Another limitation concerns the large number of models we tested, which increases the risk of cumulative Type-I errors. Note, however, that despite the potential problems associated with multiple testing, we did obtain theoretically meaningful results, which makes us confident about the validity of our results.

Conclusion

The present study provided support for the assumption that contextual factors play an important role in female sexual responding. In general, we found that women’s desire for emotional closeness predisposes them to participate in sexual activity which in itself contributes to future intimacy and closeness. This finding was, however, not uniform to all women, in all circumstances, and in all stages of the relationship, which indicates the importance of specifying the conditions under which the link between relational and sexual responses is most pertinent. This study also emphasizes the importance of including interpersonal variables and examining cross-partner effects in order to create more valid models on sexual responding that are better aligned with the complex reality of having sex in a relationship (Clement, 2002; Tiefer, Hall, & Tavris, 2002).

Although it may seem plausible to consider different models for male and female sexual responding, we have to be cautious not to draw a stark, caricatured dichotomy that portrays men’s sexual desire as an active, internally driven force that evolves independently of context and progresses in a linear way, whereas women would display a passive type of desire that occurs only when the context is just right and depends on the level of intimacy and commitment with their partner. In fact, assuming that there is one “normal” sexual response for men and women may seem arbitrary when considering that (1) all desire is essentially responsive to incentive stimuli (Both & Everaerd, 2002; Both, Everaerd, & Laan, 2007; Laan & Everaerd, 1995; Toates, 2009); (2) sexual responding is diverse and thus not strictly relational (Janssen, McBride, Yarber, Hill, & Butler, 2008; Meana, 2010; Meston & Buss, 2007); (3) intimacy needs are usually implicated when having sex in the context of a relationship (Dewitte, 2014); and (4) both sexual and non-sexual outcomes influence motivation for future intimacy (Basson, 2000; Meston & Buss, 2007). This diversity has important clinical implications because we have to avoid defining men and especially women as having a sexual dysfunction simply because their sexual response does not fit a particular model. As Basson (2015) has noted, variability is evident both between and within individuals and is influenced by numerous factors, including stage of life cycle, mental health, and relationship happiness. Given this variability, clinicians need to determine the sequence of sexual responding for each individual and identify at which point and under which circumstances the sequence of responding is stagnated or inhibited.

Notes

The terms sexual response and sexual responding are used here as collective labels to refer to the varied set of sexual behaviors and experiences, both internally (i.e., attitudes, beliefs, desire, fantasies) and externally (i.e., sexual acts, sexual communication).

In addition to relationship quality, participants also reported daily on other relationship and personal variables such as mood, levels of stress, own and perceived partner responsiveness, and sexual attractiveness. The analyses on these variables are reported elsewhere (Dewitte, Van Lankveld, Van den Berghe, & Loeys, 2016).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Arrindell, W. A., Boelens, W., & Lambert, H. (1983). On the psychometric properties of the Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ): Evaluation of self-ratings in distressed and ‘normal’ volunteer couples based on the Dutch version. Personality and Individual Differences, 4, 293–306.

Basson, R. (2000). The female sexual response: A different model. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 51–65.

Basson, R. (2005). Women’s sexual dysfunction: Revised and expanded definitions. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 172, 1327–1333.

Basson, R. (2015). Human sexual response. In M. P. Islam & S. E. Roach (Eds.), Handbook of clinical neurology (pp. 415–434). New York: Elsevier.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 347–374.

Beck, J. G., Bozman, A. W., & Qualtrough, T. (1991). The experience of sexual desire: Psychological correlates in a college sample. Journal of Sex Research, 28, 443–456.

Birnbaum, G. E., & Laser-Brandt, D. (2002). Gender differences in the experience of heterosexual intercourse. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 11, 143–158.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616.

Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J.-P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York: Guilford Press.

Both, S., & Everaerd, W. (2002). Comment on “The Female Sexual Response: Different Model”. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28, 11–16.

Both, S., Everaerd, W., & Laan, E. (2007). Desire emerges from excitement: A psychophysiological perspective on sexual motivation. In E. Janssen (Ed.), The psychophysiology of sex (pp. 327–339). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Burleson, M. H., Trevathan, W. R., & Todd, M. (2007). In the mood for love or vice versa? Exploring the relations among sexual activity, physical affection, affect, and stress in the daily lives of mid-aged women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 357–368.

Buss, D. M. (2003). The evolution of desire: Strategies of human mating. New York: Basic Books.

Call, V., Sprecher, S., & Schwartz, P. (1995). The incidence and frequency of marital sex in a national sample. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 639–652.

Carpenter, L. M., Nathanson, C. A., & Kim, Y. J. (2009). Physical women, emotional men: Gender and sexual satisfaction in midlife. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 87–107.

Christopher, F. S., & Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 999–1017.

Clement, U. (2002). Sex in long-term relationships: A systemic approach to sexual desire problems. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 241–246.

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577.

Debrot, A., Meuwly, N., Muise, A., Impett, E. A., & Schoebi, D. (2017). More than just sex: Affection mediates the association between sexual activity and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 287–299.

Dewitte, M. (2014). On the interpersonal dynamics of sexuality. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 40, 209–232.

Dewitte, M., Van Lankveld, J., Van den Berghe, S., & Loeys, T. (2016). Sex in its daily relational context. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 2436–2450.

Diamond, L. M. (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110, 173–192.

Elmerstig, E., Wijma, B., & Berterö, C. (2008). Why do young women continue to have sexual intercourse despite pain? Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 357–363.

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., & Downey, G. (2003). He said, she said: A quasi-signal detection analysis of daily interactions between close relationship partners. Psychological Science, 14, 100–105.

Giles, K. R., & Mc Cabe, M. P. (2009). Conceptualizing women’s sexual function: Linear vs. circular models of sexual response. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 2761–2771.

Giraldi, A., Kristensen, E., & Sand, M. (2015). Endorsement of models describing sexual response of men and women with a sexual partner: An online survey in a population sample of Danish adults ages 20–65 years. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 116–128.

Hayes, R. D. (2011). Circular and linear modeling of female sexual desire and arousal. Journal of Sex Research, 48, 130–141.

Hinchliff, S., & Gott, M. (2004). Intimacy, commitment, and adaptation: Sexual relationships within long-term marriages. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 595–609.

Janssen, E., McBride, K. R., Yarber, W., Hill, B. J., & Butler, S. M. (2008). Factors that influence sexual arousal in men: A focus group study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 252–265.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Newton, T. L. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503.

Klinger, E. (1975). Consequences of commitment to and disengagement from incentives. Psychological Review, 82, 1–25.

Klusmann, D. (2002). Sexual motivation and the duration of partnership. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 275–287.

Laan, E., & Everaerd, W. (1995). Habituation of female sexual arousal to slides and film. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24, 517–541.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, R. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281, 537–544.

Laurenceau, J. P., Feldman Barrett, L., & Rovine, M. J. (2005). The Interpersonal Process Model of Intimacy in Marriage: A daily–diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 314–325.

Levine, S. B. (2003). The nature of sexual desire: A clinician’s perspective. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 279–285.

Liu, C. (2000). A theory of marital sexual life. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 363–374.

Liu, C. (2003). Does quality of marital sex decline with duration? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 55–60.

Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. (1966). Human sexual response. Boston: Little, Brown.

McNulty, J. K., Wenner, C. A., & Fisher, T. D. (2016). Longitudinal associations among relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction and frequency of sex in early marriage. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 85–97.

Meana, M. (2010). Elucidating women’s (hetero)sexual desire: Definitional challenges and content expansion. Journal of Sex Research, 47, 104–122.

Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 477–507.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.) [Computer software manual]. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Orathinkal, J., Vansteenwegen, A., Enright, R. D., & Stroobants, R. (2007). Further validation of the Dutch version of the Enright Forgiveness Inventory. Community Mental Health Journal, 43, 109–128.

Peplau, L. A. (2003). Human sexuality: How do men and women differ? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 37–40.

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 21–38.

Regan, P. C., & Berscheid, E. (1995). Gender differences in beliefs about the causes of male and female sexual desire. Personal Relationships, 2, 345–358.

Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., … D‘Agostino, J. R. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 191–208.

Rosen, R. C., Riley, A., Wagner, G., Osterloh, I. H., Kirkpatrick, J., & Mishra, A. (1997). The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology, 49, 822–830.

Sand, M., & Fisher, W. A. (2007). Women’s endorsement of models of female sexual response: The Nurses’ Sexuality Study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4, 708–719.

Schröder, J., & Schmiedeberg, C. (2015). Effects of relationship duration, cohabitation, and marriage on the frequency of intercourse in couples: Findings from German panel data. Social Science Research, 52, 72–82.

Spector, I. P., Carey, M. P., & Steinberg, L. (1986). The Sexual Desire Inventory: Development, factor structure, and evidence of reliability. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 22, 175–190.

Sprecher, S., & Cate, R. M. (2004). Sexual satisfaction and sexual expression as predictors of relationship satisfaction and stability. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 235–256). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ter Kuile, M. M., Brauer, M., & Laan, E. (2006). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): Psychometric properties within a Dutch population. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 32, 289–304.

Tidwell, M. C. O., Reis, H. T., & Shaver, P. R. (1996). Attachment, attractiveness, and social interaction: A diary study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 729–745.

Tiefer, L., Hall, M., & Tavris, C. (2002). Beyond dysfunction: A new view of women’s sexual problems. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28, 225–232.

Toates, F. (2009). An integrative theoretical framework for understanding sexual motivation, arousal and behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 46, 168–193.

Acknowledgment

The research reported in this paper was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship grant of the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (Belgium) (F.W.O.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dewitte, M., Mayer, A. Exploring the Link Between Daily Relationship Quality, Sexual Desire, and Sexual Activity in Couples. Arch Sex Behav 47, 1675–1686 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1175-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1175-x