Abstract

Obesity is associated with functional limitations in muscle performance and increased likelihood of developing a functional disability such as mobility, strength, postural and dynamic balance limitations. The consensus is that obese individuals, regardless of age, have a greater absolute maximum muscle strength compared to non-obese persons, suggesting that increased adiposity acts as a chronic overload stimulus on the antigravity muscles (e.g., quadriceps and calf), thus increasing muscle size and strength. However, when maximum muscular strength is normalised to body mass, obese individuals appear weaker. This relative weakness may be caused by reduced mobility, neural adaptations and changes in muscle morphology. Discrepancies in the literature remain for maximal strength normalised to muscle mass (muscle quality) and can potentially be explained through accounting for the measurement protocol contributing to muscle strength capacity that need to be explored in more depth such as antagonist muscle co-activation, muscle architecture, a criterion valid measurement of muscle size and an accurate measurement of physical activity levels. Current evidence demonstrating the effect of obesity on muscle quality is limited. These factors not being recorded in some of the existing literature suggest a potential underestimation of muscle force either in terms of absolute force production or relative to muscle mass; thus the true effect of obesity upon skeletal muscle size, structure and function, including any interactions with ageing effects, remains to be elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity is a prominent public health concern. Within the UK the proportion of clinically obese adults has increased from 17.5 to 26.1 % between 1996 and 2010 (National Centre for Social Research 2011), and these figures are predicted to rise to 47 % of all men and 36 % of all women by 2025 (Butland et al. 2007). The problem with the rising level of obesity is the associated increased risk in developing a variety of conditions, such as non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (DM; Steppan et al. 2001), cardiovascular disease (Larsson et al. 1984), coronary heart disease (Manson et al. 1990), hypertension (Manicardi et al. 1986), stroke (Song et al. 2004) and cancer (Bianchini et al. 2002). In addition to these co-morbidities, obesity has been shown to have a negative impact on skeletal muscle through adolescence (Blimkie et al. 1990; Maffiuletti et al. 2008) to both young (Hulens et al. 2001; Maffiuletti et al. 2007) and old adulthood (Zoico et al. 2004; Rolland et al. 2004).

Researchers have examined the effect obesity has on maximal isotonic (Lafortuna et al. 2005), isometric (Tomlinson et al. 2014a) and isokinetic (Blimkie et al. 1990; Maffiuletti et al. 2007; Hulens et al. 2001, 2002; Delmonico et al. 2009; Hilton et al. 2008) strength in a variety of age classifications ranging from adolescents to the elderly. The majority of these studies with the focus being predominantly in the lower limbs, agree that absolute strength is higher in obese compared to non-obese individuals, and the consensus between all studies is that strength is lower in the loaded musculature when normalised to total body mass. The implications for reduced strength relative to body mass in the lower limbs are foremost relevant to an older population, as these are normally affected by a reduced functional capacity (e.g., difficulty walking, stairs negotiation and rising from a chair or bed) (LaRoche et al. 2011; Rolland et al. 2009; Maden-Wilkinson et al. 2015) and an increased risk of joint pathologies (e.g., knee and hip osteoarthritis) (Cooper et al. 1998; Slemenda et al. 1998) initiated through low muscle strength increasing joint loads (Mikesky et al. 2000) thus increasing the likelihood of developing osteoarthritis and additionally aiding in the progression of the condition, and leading to a reduced quality of life. Accompanying rising age and obesity is the potential increase and effect intramuscular fat has upon muscle mechanics, through lowering muscle quality (Rahemi et al. 2015), however this has not been confirmed in human in vivo research. Therefore, understanding the adaptations of skeletal muscle of individuals who are classified obese across all age groups with specific focus on the elderly needs to be a priority, owing to the combination of a demography of increased prevalence of obesity supplemented with increased life expectancy (Kirkwood 2008).

It is possible that lower relative strength in older obese people when compared to their normal weight counterparts (Tomlinson et al. 2014a) may partly be modulated via a higher state of systemic inflammation (Schrager et al. 2007), as fat deposits can act as endocrine organ secreting various pro-inflammatory cytokines. This hypothesis is supported through obesity-related increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines, specifically interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α; Schrager et al. 2007). Cytokines are in fact associated with lower muscle mass and strength in the elderly (presumably through stimulating muscle protein catabolism and inhibiting muscle protein synthesis) (Visser et al. 2002). These effects may be compounded by impaired skeletal muscle regeneration capacity in obese individuals as hypothesised by Akhmedov and Berdeaux (2013). This has yet to be confirmed in a human population, however animal models have demonstrated an impaired regenerative capacity in obese and diabetic mice (Nguyen et al. 2011) with the mechanism suggested as being through compromised satellite cell function due to lipid overload (Akhmedov and Berdeaux 2013). Yet, the specific effect that chronically high levels of adiposity combined with ageing-associated systemic inflammation and impaired skeletal muscle regenerative capacity may have upon skeletal muscle structure and function is yet to be fully understood.

Therefore, the aim of this review was to examine the known link between adiposity and skeletal muscle force and power generation through adolescence, to young adults and finally old age.

Does the extra loading of adiposity seen in obesity, act as a training stimulus on skeletal muscle throughout the ages?

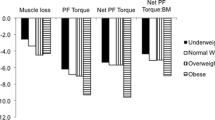

Investigations into the effects of obesity on muscle size and function have described the inter-link between muscle torque and power to body mass, where obese people elicited higher absolute maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) torque and power than normal-weight individuals (Blimkie et al. 1990; Lafortuna et al. 2005; Hulens et al. 2001; Maffiuletti et al. 2007, 2008; Abdelmoula et al. 2012). A rationale for higher absolute MVC torque and power in obese individuals is from the suggestion by Thoren et al. (1973) that extra mass from high levels of fat mass seen in obese individuals might elicit a positive training stimulus on skeletal muscle (see Fig. 1). This hypothesis was strengthened by Bosco et al. (1986) who reported increases in muscle power in anti-gravity muscles following 3 weeks of simulated hypergravity through the use of weighted vests. The weighted vests (7–8 % body mass) utilised in this study were worn from morning until evening similar to the excess (fat) mass an obese individual would carry around daily. It is crucial to note that the duration of this study does not replicate the length of time adiposity acts as a loading stimulus to an obese individual; in addition, all participants were healthy normal weight individuals. This study nonetheless provides a comparable stimulus to the loaded anti-gravity musculature of the lower limbs faced by obese individuals during daily activities for an acute period. The causative explanations given by Bosco et al. (1986) for the increase in performance were through increased motor unit firing rate, additional recruitment of motor units and the synchronisation of these motor units. These specific neural adaptations are accepted to occur in the initial phase of resistance training, with hypertrophy becoming the dominant factor after 3–5 weeks (Moritani and deVries 1979). However, due to the gradual and sustained increases in fat mass that an obese individual would experience, the adaptations to skeletal muscle of an obese individual may differ from that of a healthy individual undertaking loaded resistance exercise. Therefore, this elicits the question that if individuals are obese for numerous years, would this increase muscle strength in the lower limbs through carrying higher inert mass (i.e., adipose tissue) during daily activities?

Representative DEXA scans taken from Tomlinson et al. (2014b) of a (i) young obese female versus young normal weight female and (ii) old obese female versus old normal weight female. Colour key: blue for bone, red for lean tissue, yellow for adipose tissue. (Color figure online)

The effect of obesity on muscle strength and structure in adolescent individuals

By assessing both neural and muscular components of force generating capacity, Blimkie et al. (1990) were the first to extensively examine skeletal muscle performance in obese and non-obese adolescent males. The main observation from the Blimkie study was lower quadriceps femoris muscle activation in obese compared to non-obese adolescent males (85.1 vs. 95.2 %; 100 % = complete voluntary muscle activation). The obese adolescents studied by Blimkie et al. (1990) were outpatients at a children’s exercise and nutrition centre, while the non-obese adolescents were selected from a local secondary school. It is not known whether the two cohorts were matched for habitual physical activity levels. Any potential differences in physical activity may have explained some of the variability in neuromuscular variables, such as agonist muscle activation and antagonist muscle co-activation (Martinez-Gomez et al. 2011; Moliner-Urdiales et al. 2010; Ramsay et al. 1990), which may have also confounded any potential difference in strength between obese and non-obese boys (Blimkie et al. 1990). Notwithstanding potential differences in the habitual physical activity background of the study participants, the data suggested that relative to their non-obese counterparts, obese adolescents had poorer neural activation capacity, likely leading to a reduction in the degree and/or pattern of muscle fibre recruitment. Yet it has been shown in an adult population that high levels of visceral adiposity is associated with increased neural sympathetic drive (Alvarez et al. 2002).

Interestingly in the Blimkie et al. (1990) study, there were no between group (obese vs. non-obese) differences in absolute isometric strength at a variety of muscle lengths (20°, 40°, 60°, 90° of knee extension) or in isokinetic knee strength (30, 60, 120 and 180°/s). These results differ from later work by Maffiuletti et al. (2008), who reported significantly higher absolute voluntary isometric strength in the obese adolescent at short muscle lengths (+25 % at 40° extension) and during isokinetic efforts (+16 %).

However, the strength in the design of the Maffiuletti et al. (2008) study in comparison to Blimkie et al. (1990) was the control of physical activity in the adolescent males, as the exclusion criteria stated that no individual took part in rigorous physical activity and undertook less than 2 h/week of recreational physical activity. In other words, the fact that Maffiuletti et al. (2008) considered physical activity levels but Blimkie et al. (1990) did not, may in turn account for the disparity in the reported impact of obesity between the two studies. This is due to previously reported data demonstrating that vigorous levels of physical activity can increase strength in the anti-gravity muscles of the lower limb (Moliner-Urdiales et al. 2010). However, Maffiuletti et al. (2008) proposed that a rationale for significantly higher strength at short muscle lengths in the obese adolescent cohort could be their preferentially working at shorter muscle lengths to avoid excessive stress during an activity/sport or to avoid injury. Such a habitual loading protocol would shift the length–tension relationship to the left, hence placing obese adolescents at a disadvantage in daily activities involving a wider range of movement (e.g., deep squatting, getting up from a chair, walking fast, bending).

Similarly to Maffiuletti et al. (2008), others such as Abdelmoula et al. (2012) reported higher absolute maximum isometric knee extension torque (+24 % at 60° of extension) and lower MVC torque relative to body mass (−25 %) in obese compared to non-obese adolescent males. Interestingly, Abdelmoula et al. (2012) reported higher MVC isometric torque normalised to thigh lean mass (+17.9 %) and estimated thigh muscle mass (+22.2 %). This differs from reports by both Blimkie et al. (1990) and Maffiuletti et al. (2008), who reported no significant differences in MVC knee extension torque normalised to quadriceps anatomical cross sectional area (ACSA) (Blimkie et al. 1990) or fat free mass (FFM; Maffiuletti et al. 2008). The discrepancies within these studies may be due to differences in the methodology in assessing thigh/quadriceps muscle mass. Indeed the gold standard in the assessment of muscle size is the physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA) as it accounts for the pennate architecture of the quadricep femoris muscle group. However, Abdelmoula et al. (2012) attributed the higher strength relative to estimated muscle mass in their study sample, to higher agonist muscle activation and lower antagonist muscle co-activation in the obese adolescents. It is noteworthy that whilst Abdelmoula et al. (2012) did measure muscle mass/volume, this could not explain the higher force seen in the obese. It is thus possible that higher muscle activation is indeed a potential explanation but as this was not measured, it remains unclear what explains the higher force in their study. The higher force in the Abdelmoula study may in fact also be due to a greater proportion of faster fibre (Clark et al. 2011). This proposal however is tempered by studies that show there is no real difference in specific tension between slow and fast fibres, and if present this would only explain a small proportion of the difference seen (Ballak et al. 2014). Interestingly, the obese adolescents had lower habitual physical activity levels, which one would normally expect to lead to a lowering in muscle activation capacity (Martinez-Gomez et al. 2011). Indeed as reported earlier, Blimkie et al. (1990) found muscle activation to be significantly lower in obese adolescent boys. Abdelmoula et al. (2012) also proposed that there could have been an increase in the contribution from the synergistic muscles in obese adolescent boys. Whether there may be an obesity-induced alteration in muscle recruitment strategy in young adolescents has yet to be demonstrated. However, it needs to be noted that there is a lack of research examining the neural responses into maximal strength capacity in adolescent obese individuals after controlling for physical activity levels. Further research examining this variable need to investigate both agonist activation using the interpolated twitch technique and antagonist co-activation using surface electromyography to rule out potential differences between obese and normal weight adolescent individuals. In parallel, we would propose an alternative rationale for the higher strength values relative to estimated muscle mass in the Abdelmoula et al. study (2012): the differences in the intrinsic properties of the skeletal muscle of the two cohorts. In support of this hypothesis, previous research demonstrates an increase in fast twitch fibres in obese 26–62 year old adults (Kriketos et al. 1997). The potential shift in fibre type may be explained by the lower physical activity levels of the obese creating an effect similar to what is observed in a detraining model (Staron et al. 1991). Such an effect, however, has yet to be confirmed in an obese adolescent population and in many ways, is opposite to the idea of loading through fat acting as an additional load.

In summary, the general consensus is that obese adolescents exhibit lower relative strength to body mass (see Table 1). Yet discrepancies exist when examining the absolute strength of obese versus non-obese adolescents and strength relative to muscle mass (muscle quality). These differences between studies may be attributed to variability in the methodology, including the control of habitual physical activity difference between participant groups, and/or the methods utilised in the quantification of muscle size. However, current evidence suggests that there is no effect of obesity on muscle quality, but as noted above methodological issues need to be resolved. Interestingly, it has previously been reported that obese adolescents have lower agonist voluntary muscle activation. The implication of this is the potential to underestimate the strength capabilities of obese adolescents in studies not correcting for this variable. Yet, no study to date has examined the effect of antagonist co-activation has upon maximal torque output in obese versus non-obese adolescent individuals thus potentially leading to further underestimating the quality of the muscle exposed to obesity. Further research in adolescents should focus on examining the variables that affect strength production such as agonist muscle activation, antagonist co-activation, PCSA and moment arm length.

The effect of obesity on muscle strength and structure in young and old adults

One of the first studies to investigate the effects of obesity on muscle strength in an adult population was conducted by Hulens et al. (2001). The authors found that the obese females had significantly higher isokinetic knee extension, trunk extension, flexion and rotational torque than the lean individuals, whilst no impact of obesity was found on handgrip strength suggesting an obesity ‘advantage’ in terms of absolute muscle strength for the loaded musculature. The mean age of the obese cohort was 39 years spanning a large age range (20–65 years), which may have confounded any effect of obesity on skeletal muscle force, as ageing is associated with a decrease in maximal muscle force (Morse et al. 2004). The importance of age classification and its effect on muscle strength is demonstrated in a separate study, in which Hulens et al. (2002) accounted for the confounding age factor and reported that the older obese (41–65 years) had significantly lower knee extension isokinetic MVC torque than their younger obese counterparts (18–40 years).

Hulens et al. (2001) had in fact reported that the loaded antigravity muscles of the knee extensors, back extensors and oblique abdominals were stronger in the obese compared to the lean women. Yet, when normalised to FFM, maximum knee extensor strength was significantly 6–7 % lower in the obese cohort. The discrepancy regarding absolute MVC torque and MVC torque normalised to FFM may be due to lower agonist muscle activation (as seen in adolescents Blimkie et al. 1990). Lower activation of motor units during a maximal contraction would potentially lower maximal strength generation resulting in both lower absolute and normalised MVC. Other explanations for the discrepancy of MVC torque relative to FFM could be the use of FFM instead of muscle volume or PCSA to accurately assess MVC torque relative to muscle size, due to it demonstrating an accurate in vivo representation of the maximum number of parallel-aligned sarcomeres. Interestingly, Hulens et al. (2001) reported no differences in handgrip strength between obese and non-obese individuals opposite to his findings on absolute knee extensor strength, suggesting the additional body mass may act as a training stimulus, i.e., overloading the anti-gravity muscles in a similar way that performance has been shown to increase with the use of a weighted vest (Bosco et al. 1984). Hulens et al. (2001) supported this finding by demonstrating MVC torque relative to FFM during knee flexion was 18–20 % lower in obese versus non-obese individuals, while MVC knee extension torque was only 6–7 % lower, which would suggest that the additional fat mass is a larger training load for the extensors than the flexors. This hypothesis is supported by resistance training being associated with an increase in skeletal muscle specific tension (Erskine et al. 2010).

Lafortuna et al. (2005) went further to examine gender differences in body composition, muscle strength and power output in 95 morbidly obese adults (28 men and 67 women) aged 29 ± 7 years. Body composition was analysed with bioelectrical impedance, while muscle strength of both the upper and lower limbs was assessed using isotonic gym equipment (chest press and leg press) and power output assessed by a standing vertical jump. The main findings of the study by Lafortuna et al. (2005) revealed that obese young men were significantly stronger in both upper and lower limbs and more powerful than the obese young women, and these differences were attributed to greater FFM in the men (77.7 vs. 52 kg), a result which was expected since males tend to demonstrate this effect even in non-obese young adult populations (Janssen et al. 2000). Interestingly, when isotonic strength was normalised to FFM, all differences disappeared between genders in both the obese and normal weight participants. In terms of lower limb power output normalised to FFM, data showed obese males to have lower relative power to FFM than their normal weight counterparts and in addition it showed a strong though non-significant trend for a gender effect (p = 0.059). This could be caused by a change in the intrinsic properties of the skeletal muscle of the lower limb, through a shift in fibre type composition to slower twitch fibres. This further supports the theorem that high body mass loads the antigravity muscles similarly to resistance training, thus causing a fast–slow transition in fibre type composition (Staron et al. 1994). This is demonstrated by a mean difference of 20 kg more inert body mass seen in the obese males than the obese females (128 vs. 108 kg) acting as potential enhanced loading stimulus during daily living activities. The isotonic upper body strength measures reported in this study support this hypothesis, as no differences were reported in upper body strength between normal weight and obese participants irrespective of gender, yet significant strength differences were observed in the anti-gravity muscles during the leg press efforts.

Maffiuletti et al. (2007) reported obese males to have higher absolute torque at all angles and velocities suggesting that, in an adult population, obese individuals do not appear to favourably work at a specific muscle length, contrary to adolescents who exhibit higher absolute strength at short muscle lengths (Maffiuletti et al. 2008). These differences may be explained through obese adolescents preferentially working at shorter muscle lengths as a mechanism to facilitate the accomplishment of habitual daily activities (e.g., shallow/small squats); however this needs further investigation. At their optimal angle and peak velocity obese individuals had 16 and 20 % higher absolute isometric and isokinetic torque, respectively, compared with their non-obese counterparts. Yet, when normalising absolute strength to body mass, maximum isometric and isokinetic knee extension joint torque were respectively 34.5 and 32.5 % lower than in normal-weight individuals similar to previous work in an adult population (Hulens et al. 2001; Lafortuna et al. 2005). However, when both isometric and isokinetic MVC torque were normalised to FFM, any significant differences between cohorts disappeared. It should be noted that the standardisation of MVC torque to total FFM does not differentiate the quadriceps femoris muscle group from other muscle groups, hence extraneous synergistic/antagonistic muscles to knee extension efforts would have confounded the authors’ concluding remarks. Furthermore, MVC joint torque is influenced by additional factors such as voluntary muscle activation capacity, antagonist muscle co-activation and the tendon moment arm (Erskine et al. 2009), which were not considered in this study. To date however, no study has accounted for these differences within the current literature in an adult population when comparing obese–non-obese.

Further research by Maffiuletti et al. (2005) reported that obese individuals have inadequate postural stability when compared to lean persons. These balance issues were improved after a few postural stability-training sessions during a body weight reduction programme. This finding has implications for the prevention of falls, especially in obese elderly individuals who are more at risk of falls and fractures (Himes and Reynolds 2012). Interestingly, the majority of studies investigating the effect of obesity on muscle strength have focussed on the knee extensors. Yet, as demonstrated by Maffiuletti et al. (2005), the contribution of the plantar flexors during postural stability (Onambele et al. 2006) suggests more work should focus on this muscle group when examining the effect of obesity on muscle function.

Hilton et al. (2008) was one of the primary investigators to focus on the plantar flexors. Contrary to the findings of Hulens et al. (2001, 2002), Lafortuna et al. (2005) and Maffiuletti et al. (2007), Hilton et al. (2008) reported that MVC torque and lower limb power were lower in obese compared to non-obese people, both in absolute terms and when power was normalised to muscle volume. Importantly to note, is that the sample size of this study was small (n = 6, BMI = 36 ± 8 vs. n = 6, BMI 28 ± 6) and the obese subjects in this study had DM and peripheral neuropathy. DM is strongly associated with both obesity (Mokdad et al. 2003), and peripheral neuropathy (Young et al. 1993), which is characterised by nerve damage, leading to reduced neural function, motor dysfunction (Andersen et al. 1997) and reduced strength (Andersen et al. 1996). The rationale for lower muscle strength in the obese/peripheral neuropathy cohort of the Hilton et al. (2008) study is likely to be the result of DM-induced neuropathy negatively affecting muscle force generation. Interestingly, individuals only classified obese with no signs of peripheral neuropathy have shown reduced neural function as previously demonstrated by lower muscle activation in both obese versus lean adolescents (Blimkie et al. 1990) and high adiposity versus normal adiposity young adults aged between 18 and 49 years old (Tomlinson et al. 2014a, b, c). Nevertheless more research is necessary to confirm if this is also the case in older adults, and to what degree ageing may impact on any association between obesity and muscle-strength. What is clear however, is that one link is likely to be through increased TNF-α levels in both obesity and insulin resistance (Hotamisligil et al. 1995) which has an apoptotic effect on skeletal muscle tissue (Kewalramani et al. 2010) and would in that manner, negatively impact on the function of the muscle-tendon unit as a whole.

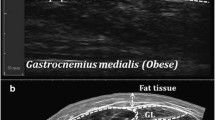

Our own research (Tomlinson et al. 2014a) reported obese adult females (18–49 years old) to have significantly greater plantar flexor strength that their age matched normal and underweight counterparts. This study was the first to control for both antagonist co-contraction and agonist muscle activation during maximal isometric contraction in any age classification. Further research in our group Tomlinson et al. (2014b) also revealed lower maximal strength in an obese adult female cohort when plantar flexion strength was computed relative to gastrocnemius medialis muscle volume. However, after accounting for both the physiological (antagonist co-contraction, agonist muscle activation, PCSA and pennation angle) and biomechanical (moment arm length) determinants of maximal strength capability, all significant differences were removed between both BMI and adiposity classification.

In addition to these findings both Lafortuna et al. (2013) and our own investigations (Tomlinson et al. 2014c) report increasing BMI and adiposity to be associated with increased skeletal muscle volume in a young adult population (18–49 years old), thus explaining a rise in isometric strength demonstrated in the obese (Tomlinson et al. 2014b). Interestingly, Lafortuna et al. (2013) revealed a similar observation as the male obese cohort had greater muscle mass which may be attributed to alterations in the relative levels of cytokines and anabolic hormones (Tipton 2001).

In summary, an analysis of studies in an adult population suggests that obese individuals have significantly higher absolute strength, but lower strength normalised to body mass in the antigravity muscles of the lower limb (see Table 2). However, upper limb strength data reveals no statistical difference between obese and normal weight individuals. This suggests that the loading brought about through higher inert mass (increased adiposity) simulates a resistance-training stimulus, but only specifically to the weight bearing (i.e., antigravity) musculature. Interestingly, when absolute strength measures are made relative to FFM, all significant differences between obese and non-obese cohorts are erased in the majority of cases. However, the use of total body FFM (instead of using PCSA) does not account for the pennate architecture of the knee extensors or plantar flexors, thus potentially confounding the statistical differences between cohorts. Interestingly, the combined effect of obesity coupled with the co-morbidities of DM highlights the detrimental effect of high adipose tissue content in terms of lowering absolute and relative strength through motor dysfunction, and thus negatively impacting on activities of daily living.

The interaction between age and obesity, and its effect on skeletal muscle (sarcopenic obesity)

The age related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function has been termed “sarcopenia” (Narici and Maffulli 2010; Rosenberg 1997). Sarcopenia has been shown to increase the risk of developing functional limitations (e.g., walking and climbing stairs) and physical disabilities as defined by the difficulty in performing daily activities (e.g., shopping, household chores and making meals) (Janssen et al. 2002). Therefore, reversing, delaying, and/or preventing the development of sarcopenia and maintaining functional mobility is paramount to ensuring a good quality of later life. There does not appear to be a single cause for sarcopenia as it is linked with decreased physical activity, chronic systemic inflammation and neuropathic changes leading to motor neuron death and denervation of muscle fibres (Campbell et al. 1973; Degens 2010). However, the presence of obesity coupled with sarcopenia has been shown to exacerbate functional limitations, increasing the difficulty in performing physical functions that require strength (Rolland et al. 2009). Baumgartner et al. (2004) defined the combination of these morbidities as ‘sarcopenic obesity’. Individuals were classified as sarcopenic obese through having an appendicular skeletal muscle mass index [skeletal muscle mass (kg) ÷ stature2 (m2)] greater than two standard deviations below that of a 20–30 years old young adult reference group (Baumgartner et al. 1998), combined with a body fat percentage above the 60th percentile (Baumgartner et al. 2004).

As discussed above, obesity independent from sarcopenia, has been associated with difficulty in performing daily physical functions such as lifting heavy objects and stair negotiation. Individuals with sarcopenic obesity have an even greater difficulty in performing these daily physical functions (Rolland et al. 2009). Rolland et al. (2009) compared self-reported difficulties with physical functions (i.e., walking, climbing stairs and rising from a chair) in 1308 healthy women aged 75 years old or older. These women were classified into one of four categories (healthy body composition, purely sarcopenic, purely obese and sarcopenic obese). The investigators reported purely sarcopenic women had no increased odds of having physical difficulties with the functional movement assessed when compared to the healthy body composition elderly females of the study. However, the purely obese were reported to have 44–79 % higher probability of having difficulty with the functional movements assessed, whilst the sarcopenic obese had a 2.6 higher probability of difficulty in climbing stairs and 2.35 higher probability of difficulty in going down stairs. Thus, it can be derived from Rolland and colleagues’ study (2009) that sarcopenia and obesity, have synergistic effects when it comes to specific functional movements.

This research was supported by Zoico et al. (2004) who reported older obese women to have a three–four times increased risk of developing functional limitations, where their BMI was higher than 30. However within this study, individuals who had class II sarcopenia (i.e., skeletal muscle mass index 2 standard deviations below a young adult reference group Janssen et al. 2002) had a similar risk of functional limitations as the females who were only characterised as obese. This research suggests that both conditions play a role in limiting physical performance during daily tasks. Potentially also, sarcopenia and obesity may interact, intensifying the unfavourable consequences of the two morbidities. A rationale for the exacerbation of sarcopenia brought about by obesity may be the increased mechanical stress to the musculo-skeletal system through carrying the inert mass of high levels of adipose tissue evident in obesity. In addition, adipose tissue is known to act as an endocrine organ, secreting numerous hormones and inflammatory cytokines (Ahima and Flier 2000), hence enhancing biochemical stress. Obese individuals store chronically high levels of adipose tissue, which causes an increase in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (Hotamisligil et al. 1995). Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α (Hotamisligil et al. 1995), IL-1α (Juge-Aubry et al. 2003), IL-6 (Park et al. 2005) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (Park et al. 2005) play a role in cell signalling in the response to both acute and chronic systemic inflammation and can have a detrimental impact on skeletal muscle by stimulating muscle protein degradation (Garcia-Martinez et al. 1993) causing muscle wasting/atrophy and reducing muscle protein synthesis (Mercier et al. 2002). The initiation of muscle wasting/atrophy is modulated via numerous mechanisms such as activation of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Cao et al. 2005; Degens 2010; Saini et al. 2006), which has been shown to be effected via TNF-α (Llovera et al. 1998). Chronically high levels of TNF-α initiates protein degradation and decreased protein synthesis (Mercier et al. 2002), with the net effect being skeletal muscle atrophy (see Fig. 2).

Interplay between obesity, inflammation and skeletal muscle. Solid arrows denote events with established evidence. CRP C-reactive protein, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, IL-1β interleukin-1β, IL-6 interleukin-6, IL-8 interleukin-8, IL-10 interleukin-10, IL-1Ra interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, MIF macrophage migration inhibitory factor, NGF nerve growth factor, PGE2 prostaglandin E2, SAA 1 and 2 serum amyloid A proteins 1 and 2, SV stromovascular, TGF-β1 transforming growth factor-β1, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, IGF-1 insulin-like growth factor-1

The decrease in protein synthesis can also be related to a reduction in anabolic hormones that would otherwise promote the repair and regeneration of skeletal muscle. This is observed in the reduction in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a promoter of protein synthesis and muscle hypertrophy (DeVol et al. 1990), as reported in severely obese women (Galli et al. 2012). Notably within said study, IGF-1 levels following a surgical intervention (laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding), increased proportionately to the extent of weight loss. This therefore demonstrates that lowering adiposity can improve an individual’s anabolic profile. The inhibition of IGF-1 is thought to be initiated by the TNF-α-mediated activation of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Grounds et al. 2008). Activation of JNK has also been shown to play a role in the development of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome through diet induced obesity (Sabio et al. 2010). The overall implications of low IGF-1 levels coupled with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines in an obese individual would be a blunting of any beneficial effect of enhanced loading. Such an effect may be further exacerbated in an elderly population owing to a less than optimal endocrine milieu normally associated with normal ageing: i.e., low IGF-1, growth hormone and testosterone (Bucci et al. 2013; Lamberts et al. 1997) levels, combined with higher fat infiltration within skeletal muscle (Delmonico et al. 2009) and the ‘inflamed ageing’ phenomenon, i.e., higher circulatory levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Visser et al. 2002).

In the literature on the effects of obesity on muscle function in an elderly population, Rolland et al. (2004) examined upper and lower limb muscle strength in obese elderly women and how the effect of habitual physical activity levels contributed to any differences in maximum muscle strength between active/non-active obese elderly individuals. The study consisted of three cohorts: (i) obese (n = 215, BMI = 31.9), (ii) normal weight (n = 630, BMI = 26.3), (iii) lean (n = 598, BMI = 21.6) participants (it should be noted that participants ought here to have been categorised as obese, overweight and normal weight individuals, to be more correct on the terminology). Physical activity was controlled for and defined as being active by taking part in at least one recreational physical activity (i.e., hiking, swimming and gardening) for greater than 1 h/week. The obese individuals were shown to be less physically active than both the lean and normal weight cohorts, yet when classifying participants as either sedentary or active, obese individuals with high activity levels demonstrated higher absolute isometric knee extension strength when compared to lean individuals. However, when individuals were classed as sedentary, any significant differences between cohorts were eradicated in relation to knee extension strength. Interestingly, there was no difference in handgrip or elbow extension strength between cohorts even though obese individuals had significantly larger arm muscle mass when compared to categorised normal weight and lean individuals (Rolland et al. 2004). This may be explained by the hypothesis presented earlier regarding elevated adiposity causing additional overloading of the anti-gravity muscles (e.g., quadriceps, triceps surae) during routine daily activities, e.g., walking, climbing steps, etc. This creates an environment of hypergravity, which has been shown to increase isokinetic plantar flexor strength by 40 % in post-menopausal women following 12 weeks of resistance training using weighted vests (Klentrou et al. 2007).

This benefit of weighted exercise has also been shown in women aged between 50 and 75 years, who saw increases in muscle strength, power and lean leg mass after a 9-month training regime (Shaw and Snow 1998). In addition to these variables, the participants’ postural stability was improved in the medio-lateral direction. This specific improvement in postural balance has been shown to benefit elderly frail individuals, as most falls occur in a medio-lateral plane (Greenspan et al. 1998). Contrary to this beneficial effect of weighted exercise, obese individuals are shown to have poor postural stability (Maffiuletti et al. 2005). Thus, whilst comparisons may be made between the additional loading of a hypergravity environment against the excess loading experienced by an obese individual (through their own body mass), the detrimental consequences of obesity appear to outweigh any potential benefits of increased loading. However, as shown by Rolland and colleagues (2004), increasing physical activity levels may potentiate an increase in muscle strength thereby lessening the detrimental consequences of obesity. Interestingly in support of this idea, our own work (Tomlinson et al. 2014a) reveals that after controlling for physical activity levels, no differences in raw plantar flexor muscle strength exist between obese versus normal elderly females aged between 50 and 80 years old, when strength is corrected for antagonist co-contraction and agonist muscle activation.

Villareal et al. (2004) looked into the association between physical frailty and body composition in obese elderly (n = 52), non-obese frail elderly (n = 52) and non-obese non-frail elderly (n = 52). The classification of physical frailty was defined using three specific tests: a modified physical performance test (PPT) consisting of 7 standardised timed tasks (such as a 50 feet walk, putting on and removing a coat, standing up from a 16 inch chair 5 times and climbing a flight of stairs), Peak aerobic power (VO2 peak) using a graded treadmill test and a log of their activities during daily living. From these three tests, physical frailty was then defined if participants met two out of three of the following criteria: modified PPT score of between 18 and 32, VO2 peak of 11–18 mL/Kg/min and difficulty in performing two daily activities (Villareal et al. 2004). Within the study it was reported that the obese elderly individuals had greater absolute FFM than both non-obese frail and non-obese non-frail cohorts, yet when normalised to total body mass it was found to be lower. In addition, the obese individuals had poorer muscle quality, i.e., lower knee extension strength relative to leg lean mass, compared to their non-obese counterparts. A limitation of this assertion is that dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), as opposed to magnetic resonance imagery (MRI) or ultrasound, cannot differentiate between muscle groups. This is important, due to the potential error in relating the torque produced to whole leg lean mass instead of the muscle group undertaking the specific task.

Delmonico et al. (2009) examined the effects of sarcopenic obesity on muscle strength and physical function. They reported an age-related increase in intramuscular fat content at mid-thigh in both men and women. Due to this being a longitudinal study it was reported that after 5 years, intramuscular fat content increased irrespective of changes in body mass and subcutaneous fat in the thigh. Coupled with the increase in intramuscular fat, the data showed that the loss of knee extensor strength was two–five times greater than the loss of mid-femur muscle cross sectional area with ageing (Delmonico et al. 2009). The higher reported decrease in strength may have partly been explained by lower muscle activation and/or an increase in co-activation, which was not accounted for when measuring maximal strength. This study demonstrates that the loading effect seen in younger individuals does not attenuate the age-related loss of strength. The disproportionate loss of strength versus muscle mass was suggested through a loss in muscle quality, which has previously been reported by both Morse et al. (2005) and Goodpaster et al. (2006) in an elderly cohort. These studies suggest that the rate of force loss with ageing is similar in both obese and non-obese persons. It would not be unreasonable to expect the positive association between recreational physical activity and lower limb strength in elderly obese individuals (Rolland et al. 2004) to offset a decrease in muscle quality.

In summary, with the increase in life expectancy and the rise in obesity, it is unsurprising that sarcopenic obesity incidence is also increasing (James 2008). Whilst the body of information regarding the effects of sarcopenic obesity on skeletal muscle structure and function is increasing, there remain gaps in our knowledge. In contrast, ageing has been associated with lower agonist muscle activation (Morse et al. 2004), an increase in antagonist muscle co-activation (Klein et al. 2001), a decrease in muscle fascicle pennation angle (Morse et al. 2005) and lower muscle volume (Thom et al. 2005). To-date, these adaptations have not been systematically examined in a sarcopenic obese elderly population. However, community dwelling obese adult females have shown similar characteristics when compared to a young adult obese female population (Tomlinson et al. 2014a, b, c), obesity was shown to exacerbate the age-related physical function limitations associated with the loss of muscle mass and strength.

Conclusion

Obesity is recognised as being a worldwide epidemic and a major public health concern (James 2008). It has been reported to have detrimental implications for the functioning of skeletal muscle yet very little is known about the specific adaptations of skeletal muscle by gender and age, in the presence of chronically elevated adiposity.

The consensus within the literature is that obese individuals have reduced maximum muscle strength relative to body mass in their anti-gravity muscles compared to non-obese persons (Abdelmoula et al. 2012; Blimkie et al. 1990; Hulens et al. 2001; Lafortuna et al. 2005; Maffiuletti et al. 2007, 2008; Rolland et al. 2004; Delmonico et al. 2009). This effect on an obese individual is shown to increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis (Slemenda et al. 1998) and potentially cause functional limitations especially in the elderly (Visser et al. 2005). Evidence suggests that high levels of adiposity may impair agonist muscle activation in the young (Tomlinson et al. 2014a), adding to or perhaps leading to the functional limitation of low strength relative to body mass.

Future research is needed to systematically investigate whether body fat percentage per se may be related to agonist muscle activation (using the interpolated twitch technique) and antagonist co-activation (using surface electromyography) and/or morphological characteristics, such as muscle volume, PCSA and architecture (using gold standard techniques such MRI, computed tomography and ultrasound imaging) in the elderly focusing on individuals who are classified sarcopenic obese. Interestingly within this age classification, there appears to be a lack of longitudinal studies examining how physical/sedentary activity across the age span impacts upon the aforementioned variables. When examining the design of future work, classification of obesity should be made by adiposity (using DEXA) instead of classification by individuals BMI and classification of sarcopenia by the appendicular skeletal muscle mass index. Key also, is to determine the impact of duration of obesity, on the reported musculo-skeletal structural and functional characteristics presented during the study. Such knowledge would aid in the development of therapeutic targets.

References

Abdelmoula A, Martin V, Bouchant A, Walrand S, Lavet C, Taillardat M, Maffiuletti NA, Boisseau N, Duche P, Ratel S (2012) Knee extension strength in obese and nonobese male adolescents. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37(2):269–275. doi:10.1139/h2012-010

Ahima RS, Flier JS (2000) Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Trends Endocrinol Metab 11(8):327–332

Akhmedov D, Berdeaux R (2013) The effects of obesity on skeletal muscle regeneration. Front Physiol 4:371. doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00371

Alvarez GE, Beske SD, Ballard TP, Davy KP (2002) Sympathetic neural activation in visceral obesity. Circulation 106(20):2533–2536

Andersen H, Poulsen PL, Mogensen CE, Jakobsen J (1996) Isokinetic muscle strength in long-term IDDM patients in relation to diabetic complications. Diabetes 45(4):440–445

Andersen H, Gadeberg PC, Brock B, Jakobsen J (1997) Muscular atrophy in diabetic neuropathy: a stereological magnetic resonance imaging study. Diabetologia 40(9):1062–1069. doi:10.1007/s001250050788

Ballak SB, Degens H, Buse-Pot T, de Haan A, Jaspers RT (2014) Plantaris muscle weakness in old mice: relative contributions of changes in specific force, muscle mass, myofiber cross-sectional area, and number. Age (Dordr) 36(6):9726. doi:10.1007/s11357-014-9726-0

Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, Romero L, Heymsfield SB, Ross RR, Garry PJ, Lindeman RD (1998) Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 147(8):755–763

Baumgartner RN, Wayne SJ, Waters DL, Janssen I, Gallagher D, Morley JE (2004) Sarcopenic obesity predicts instrumental activities of daily living disability in the elderly. Obes Res 12(12):1995–2004. doi:10.1038/oby.2004.250

Bianchini F, Kaaks R, Vainio H (2002) Overweight, obesity, and cancer risk. Lancet Oncol 3(9):565–574

Blimkie CJ, Sale DG, Bar-Or O (1990) Voluntary strength, evoked twitch contractile properties and motor unit activation of knee extensors in obese and non-obese adolescent males. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 61(3–4):313–318

Bosco C, Zanon S, Rusko H, Dal Monte A, Bellotti P, Latteri F, Candeloro N, Locatelli E, Azzaro E, Pozzo R et al (1984) The influence of extra load on the mechanical behavior of skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 53(2):149–154

Bosco C, Rusko H, Hirvonen J (1986) The effect of extra-load conditioning on muscle performance in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 18 (4):415–419

Bucci L, Yani SL, Fabbri C, Bijlsma AY, Maier AB, Meskers CG, Narici MV, Jones DA, McPhee JS, Seppet E, Gapeyeva H, Paasuke M, Sipila S, Kovanen V, Stenroth L, Musaro A, Hogrel JY, Barnouin Y, Butler-Browne G, Capri M, Franceschi C, Salvioli S (2013) Circulating levels of adipokines and IGF-1 are associated with skeletal muscle strength of young and old healthy subjects. Biogerontology 14(3):261–272. doi:10.1007/s10522-013-9428-5

Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P, McPherson K, Thomas S, Mardell J, Parry V (2007) Foresight. Tackling obesities: future choices—modelling future trends in obesity and their impact on health, 2nd edn. Goverment office for science, London

Campbell MJ, McComas AJ, Petito F (1973) Physiological changes in ageing muscles. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 36(2):174–182

Cao PR, Kim HJ, Lecker SH (2005) Ubiquitin-protein ligases in muscle wasting. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37(10):2088–2097. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2004.11.010

Clark BA, Alloosh M, Wenzel JW, Sturek M, Kostrominova TY (2011) Effect of diet-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome on skeletal muscles of Ossabaw miniature swine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300(5):E848–E857. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00534.2010

Cooper C, Inskip H, Croft P, Campbell L, Smith G, McLaren M, Coggon D (1998) Individual risk factors for hip osteoarthritis: obesity, hip injury, and physical activity. Am J Epidemiol 147(6):516–522

Degens H (2010) The role of systemic inflammation in age-related muscle weakness and wasting. Scand J Med Sci Sports 20(1):28–38. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01018.x

Delmonico MJ, Harris TB, Visser M, Park SW, Conroy MB, Velasquez-Mieyer P, Boudreau R, Manini TM, Nevitt M, Newman AB, Goodpaster BH (2009) Longitudinal study of muscle strength, quality, and adipose tissue infiltration. Am J Clin Nutr 90(6):1579–1585. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28047

DeVol DL, Rotwein P, Sadow JL, Novakofski J, Bechtel PJ (1990) Activation of insulin-like growth factor gene expression during work-induced skeletal muscle growth. Am J Physiol 259(1 Pt 1):E89–E95

Erskine RM, Jones DA, Maganaris CN, Degens H (2009) In vivo specific tension of the human quadriceps femoris muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol 106(6):827–838. doi:10.1007/s00421-009-1085-7

Erskine RM, Jones DA, Williams AG, Stewart CE, Degens H (2010) Resistance training increases in vivo quadriceps femoris muscle specific tension in young men. Acta Physiol 199(1):83–89. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02085.x

Galli G, Pinchera A, Piaggi P, Fierabracci P, Giannetti M, Querci G, Scartabelli G, Manetti L, Ceccarini G, Martinelli S, Di Salvo C, Anselmino M, Bogazzi F, Landi A, Vitti P, Maffei M, Santini F (2012) Serum insulin-like growth factor-1 concentrations are reduced in severely obese women and raise after weight loss induced by laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg 22(8):1276–1280. doi:10.1007/s11695-012-0669-1

Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM (1993) Acute treatment with tumour necrosis factor-alpha induces changes in protein metabolism in rat skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biochem 125(1):11–18

Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt M, Schwartz AV, Simonsick EM, Tylavsky FA, Visser M, Newman AB (2006) The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A 61(10):1059–1064

Greenspan SL, Myers ER, Kiel DP, Parker RA, Hayes WC, Resnick NM (1998) Fall direction, bone mineral density, and function: risk factors for hip fracture in frail nursing home elderly. Am J Med 104(6):539–545

Grounds MD, Radley HG, Gebski BL, Bogoyevitch MA, Shavlakadze T (2008) Implications of cross-talk between tumour necrosis factor and insulin-like growth factor-1 signalling in skeletal muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35(7):846–851. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04868.x

Hilton TN, Tuttle LJ, Bohnert KL, Mueller MJ, Sinacore DR (2008) Excessive adipose tissue infiltration in skeletal muscle in individuals with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral neuropathy: association with performance and function. Phys Ther 88(11):1336–1344. doi:10.2522/ptj.20080079

Himes CL, Reynolds SL (2012) Effect of obesity on falls, injury, and disability. J Am Geriatr Soc 60(1):124–129. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03767.x

Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM (1995) Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Investig 95(5):2409–2415. doi:10.1172/JCI117936

Hulens M, Vansant G, Lysens R, Claessens AL, Muls E, Brumagne S (2001) Study of differences in peripheral muscle strength of lean versus obese women: an allometric approach. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25(5):676–681. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801560

Hulens M, Vansant G, Lysens R, Claessens AL, Muls E (2002) Assessment of isokinetic muscle strength in women who are obese. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 32(7):347–356

James WP (2008) WHO recognition of the global obesity epidemic. Int J Obes 32(Suppl 7):S120–S126. doi:10.1038/ijo.2008.247

Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, Ross R (2000) Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18-88 yr. J Appl Physiol 89(1):81–88

Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R (2002) Low relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability. J Am Geriatr Soc 50(5):889–896

Juge-Aubry CE, Somm E, Giusti V, Pernin A, Chicheportiche R, Verdumo C, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Burger D, Dayer JM, Meier CA (2003) Adipose tissue is a major source of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: upregulation in obesity and inflammation. Diabetes 52(5):1104–1110

Kewalramani G, Bilan PJ, Klip A (2010) Muscle insulin resistance: assault by lipids, cytokines and local macrophages. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 13(4):382–390. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833aabd9

Kirkwood TB (2008) A systematic look at an old problem. Nature 451(7179):644–647. doi:10.1038/451644a

Klein CS, Rice CL, Marsh GD (2001) Normalized force, activation, and coactivation in the arm muscles of young and old men. J Appl Physiol 91(3):1341–1349

Klentrou P, Slack J, Roy B, Ladouceur M (2007) Effects of exercise training with weighted vests on bone turnover and isokinetic strength in postmenopausal women. J Aging Phys Act 15(3):287–299

Kriketos AD, Baur LA, O’Connor J, Carey D, King S, Caterson ID, Storlien LH (1997) Muscle fibre type composition in infant and adult populations and relationships with obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 21(9):796–801

Lafortuna CL, Maffiuletti NA, Agosti F, Sartorio A (2005) Gender variations of body composition, muscle strength and power output in morbid obesity. Int J Obes 29(7):833–841. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802955

Lafortuna CL, Tresoldi D, Rizzo G (2013) Influence of body adiposity on structural characteristics of skeletal muscle in men and women. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 34(1):47–55. doi:10.1111/cpf.12062

Lamberts SW, van den Beld AW, van der Lely AJ (1997) The endocrinology of aging. Science 278(5337):419–424

LaRoche DP, Kralian RJ, Millett ED (2011) Fat mass limits lower-extremity relative strength and maximal walking performance in older women. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 21(5):754–761. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.07.006

Larsson B, Svardsudd K, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L, Bjorntorp P, Tibblin G (1984) Abdominal adipose tissue distribution, obesity, and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: 13 year follow up of participants in the study of men born in 1913. Br Med J 288(6428):1401–1404

Llovera M, Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano J, Agell N, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Garcia I, Argiles JM (1998) Protein turnover in skeletal muscle of tumour-bearing transgenic mice overexpressing the soluble TNF receptor-1. Cancer Lett 130(1–2):19–27

Maden-Wilkinson TM, McPhee JS, Jones DA, Degens H (2015) Age-related loss of muscle mass, strength, and power and their association with mobility in recreationally-active older adults in the United Kingdom. J Aging Phys Act 23(3):352–360. doi:10.1123/japa.2013-0219

Maffiuletti NA, Agosti F, Proietti M, Riva D, Resnik M, Lafortuna CL, Sartorio A (2005) Postural instability of extremely obese individuals improves after a body weight reduction program entailing specific balance training. J Endocrinol Investig 28(1):2–7

Maffiuletti NA, Jubeau M, Munzinger U, Bizzini M, Agosti F, De Col A, Lafortuna CL, Sartorio A (2007) Differences in quadriceps muscle strength and fatigue between lean and obese subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol 101(1):51–59. doi:10.1007/s00421-007-0471-2

Maffiuletti NA, Jubeau M, Agosti F, De Col A, Sartorio A (2008) Quadriceps muscle function characteristics in severely obese and nonobese adolescents. Eur J Appl Physiol 103(4):481–484. doi:10.1007/s00421-008-0737-3

Manicardi V, Camellini L, Bellodi G, Coscelli C, Ferrannini E (1986) Evidence for an association of high blood pressure and hyperinsulinemia in obese man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 62(6):1302–1304

Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Rosner B, Monson RR, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH (1990) A prospective study of obesity and risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med 322(13):882–889. doi:10.1056/NEJM199003293221303

Martinez-Gomez D, Welk GJ, Puertollano MA, Del-Campo J, Moya JM, Marcos A, Veiga OL (2011) Associations of physical activity with muscular fitness in adolescents. Scand J Med Sci Sports 21(2):310–317. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01036.x

Mercier S, Breuille D, Mosoni L, Obled C, Patureau Mirand P (2002) Chronic inflammation alters protein metabolism in several organs of adult rats. J Nutr 132(7):1921–1928

Mikesky AE, Meyer A, Thompson KL (2000) Relationship between quadriceps strength and rate of loading during gait in women. J Orthop Res 18(2):171–175. doi:10.1002/jor.1100180202

Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS (2003) Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA 289(1):76–79

Moliner-Urdiales D, Ortega FB, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Rey-Lopez JP, Gracia-Marco L, Widhalm K, Sjostrom M, Moreno LA, Castillo MJ, Ruiz JR (2010) Association of physical activity with muscular strength and fat-free mass in adolescents: the HELENA study. Eur J Appl Physiol 109(6):1119–1127. doi:10.1007/s00421-010-1457-z

Moritani T, deVries HA (1979) Neural factors versus hypertrophy in the time course of muscle strength gain. Am J Phys Med 58(3):115–130

Morse CI, Thom JM, Davis MG, Fox KR, Birch KM, Narici MV (2004) Reduced plantarflexor specific torque in the elderly is associated with a lower activation capacity. Eur J Appl Physiol 92(1–2):219–226. doi:10.1007/s00421-004-1056-y

Morse CI, Thom JM, Reeves ND, Birch KM, Narici MV (2005) In vivo physiological cross-sectional area and specific force are reduced in the gastrocnemius of elderly men. J Appl Physiol 99(3):1050–1055. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01186.2004

Narici MV, Maffulli N (2010) Sarcopenia: characteristics, mechanisms and functional significance. Br Med Bull 95:139–159. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldq008

Nguyen MH, Cheng M, Koh TJ (2011) Impaired muscle regeneration in ob/ob and db/db mice. Sci World J 11:1525–1535. doi:10.1100/tsw.2011.137

National Centre for Social Research (2011) Health Survey for England—2010. Health and Social Care Information Centre, London

Onambele GL, Narici MV, Maganaris CN (2006) Calf muscle-tendon properties and postural balance in old age. J Appl Physiol 100(6):2048–2056. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01442.2005

Park HS, Park JY, Yu R (2005) Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 69(1):29–35. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007

Rahemi H, Nigam N, Wakeling JM (2015) The effect of intramuscular fat on skeletal muscle mechanics: implications for the elderly and obese. J R Soc Interface 12(109):20150365. doi:10.1098/rsif.2015.0365

Ramsay JA, Blimkie CJ, Smith K, Garner S, MacDougall JD, Sale DG (1990) Strength training effects in prepubescent boys. Med Sci Sports Exerc 22(5):605–614

Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Pahor M, Fillaux J, Grandjean H, Vellas B (2004) Muscle strength in obese elderly women: effect of recreational physical activity in a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr 79(4):552–557

Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Cristini C, Abellan van Kan G, Janssen I, Morley JE, Vellas B (2009) Difficulties with physical function associated with obesity, sarcopenia, and sarcopenic-obesity in community-dwelling elderly women: the EPIDOS (EPIDemiologie de l’OSteoporose) Study. Am J Clin Nutr 89(6):1895–1900. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26950

Rosenberg IH (1997) Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr 127(5 Suppl):990S–991S

Sabio G, Kennedy NJ, Cavanagh-Kyros J, Jung DY, Ko HJ, Ong H, Barrett T, Kim JK, Davis RJ (2010) Role of muscle c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1 in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Mol Cell Biol 30(1):106–115. doi:10.1128/MCB.01162-09

Saini A, Al-Shanti N, Stewart CE (2006) Waste management—cytokines, growth factors and cachexia. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 17(6):475–486. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.006

Schrager MA, Metter EJ, Simonsick E, Ble A, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L (2007) Sarcopenic obesity and inflammation in the InCHIANTI study. J Appl Physiol 102(3):919–925. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00627.2006

Shaw JM, Snow CM (1998) Weighted vest exercise improves indices of fall risk in older women. J Gerontol A 53(1):M53–M58

Slemenda C, Heilman DK, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Mazzuca SA, Braunstein EM, Byrd D (1998) Reduced quadriceps strength relative to body weight: a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women? Arthritis Rheum 41(11):1951–1959. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199811)41:11<1951:AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-9

Song YM, Sung J, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S (2004) Body mass index and ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: a prospective study in Korean men. Stroke 35(4):831–836. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000119386.22691.1C

Staron RS, Leonardi MJ, Karapondo DL, Malicky ES, Falkel JE, Hagerman FC, Hikida RS (1991) Strength and skeletal muscle adaptations in heavy-resistance-trained women after detraining and retraining. J Appl Physiol (1985) 70(2):631–640

Staron RS, Karapondo DL, Kraemer WJ, Fry AC, Gordon SE, Falkel JE, Hagerman FC, Hikida RS (1994) Skeletal muscle adaptations during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women. J Appl Physiol 76(3):1247–1255

Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, Brown EJ, Banerjee RR, Wright CM, Patel HR, Ahima RS, Lazar MA (2001) The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature 409(6818):307–312. doi:10.1038/35053000

Thom JM, Morse CI, Birch KM, Narici MV (2005) Triceps surae muscle power, volume, and quality in older versus younger healthy men. J Gerontol A 60(9):1111–1117

Thoren C, Seliger V, Macek M, Vavra J, Rutenfranz J (1973) The influence of training on physical fitness in healthy children and children with chronic diseases. In: Linneweh F (ed) Current aspects of perinatology and physiology of children. Springer, Berlin, pp 83–112

Tipton KD (2001) Gender differences in protein metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 4(6):493–498

Tomlinson DJ, Erskine RM, Morse CI, Winwood K, Onambele-Pearson GL (2014a) Combined effects of body composition and ageing on joint torque, muscle activation and co-contraction in sedentary women. Age 36(3):9652. doi:10.1007/s11357-014-9652-1

Tomlinson DJ, Erskine RM, Winwood K, Morse CI, Onambele GL (2014b) Obesity decreases both whole muscle and fascicle strength in young females but only exacerbates the aging-related whole muscle level asthenia. Physiol Rep. doi:10.14814/phy2.12030

Tomlinson DJ, Erskine RM, Winwood K, Morse CI, Onambele GL (2014c) The impact of obesity on skeletal muscle architecture in untrained young vs. old women. J Anat 225(6):675–684. doi:10.1111/joa.12248

Villareal DT, Banks M, Siener C, Sinacore DR, Klein S (2004) Physical frailty and body composition in obese elderly men and women. Obes Res 12(6):913–920. doi:10.1038/oby.2004.111

Visser M, Pahor M, Taaffe DR, Goodpaster BH, Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Nevitt M, Harris TB (2002) Relationship of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with muscle mass and muscle strength in elderly men and women: the Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A 57(5):M326–M332

Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Nevitt M, Rubin SM, Simonsick EM, Harris TB (2005) Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. J Gerontol A 60(3):324–333

Young MJ, Boulton AJ, MacLeod AF, Williams DR, Sonksen PH (1993) A multicentre study of the prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the United Kingdom hospital clinic population. Diabetologia 36(2):150–154

Zoico E, Di Francesco V, Guralnik JM, Mazzali G, Bortolani A, Guariento S, Sergi G, Bosello O, Zamboni M (2004) Physical disability and muscular strength in relation to obesity and different body composition indexes in a sample of healthy elderly women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28(2):234–241. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802552

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

We confirm that we have no conflict of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomlinson, D.J., Erskine, R.M., Morse, C.I. et al. The impact of obesity on skeletal muscle strength and structure through adolescence to old age. Biogerontology 17, 467–483 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-015-9626-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-015-9626-4