Abstract

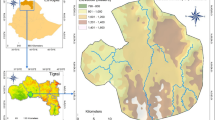

This study builds on earlier quantitative ethnobotanical studies to develop an approach which represents local values for useful forest species, in order to explore factors affecting those values. The method, based on respondents’ ranking of taxa, compares favourably with more time-consuming quantitative ethnobotanical techniques, and allows results to be differentiated according to social factors (gender and ethnic origin), and ecological and socio-economic context. We worked with 126 respondents in five indigenous and five immigrant communities within a forest-dominated landscape in the Peruvian Amazonia. There was wide variability among responses, indicating a complex of factors affecting value. The most valued family is Arecaceae, followed by Fabaceae and Moraceae. Overall, fruit and non-commercialised construction materials predominate but women tend to value fruit and other non-timber species more highly than timber, while the converse is shown by men. Indigenous respondents tend to value more the species used for fruit, domestic construction and other NTFPs, while immigrants tend to favour commercialised timber species. Across all communities, values are influenced by both markets and the availability of the taxa; as the favourite species become scarce, others replace them in perceived importance. As markets become more accessible, over-exploitation of the most valuable species and livelihood diversification contribute to a decrease in perceived value of the forest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- INRENA:

-

Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales (National Institute of Natural Resources)

- NTFP:

-

non-timber forest product

References

Baker T., Phillips O.L., Malhi Y., Almeida S., Arroyo L., Di Fiore A. et al. 2004. Increasing biomass in Amazonian forest plots. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Series B 359: 353–365.

Boom B. 1987. Ethnobotany of the Chácobo Indians, Beni, Bolivia. Advances in Economic Botany 4: 1–68.

Brown K. and Lapuyade S. 1999. ‘I have become the man of the family’. Gendered visions of social, economic and forest change in southern Cameroon. ODG Research Working Paper Overseas Development Group, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

Camara Nacional Forestal 2002. Sistema de Información Técnica y Comercial de Productos Forestales (System of Technical and Commercial Information on Forest Products). Website: http://www.madebolsaperu.com/index.htm.

Coomes O.T. and Burt G.J. 2001. Peasant charcoal production in the Peruvian Amazon: rainforest use and economic reliance. Forest Ecology and Management 140: 39–50.

Erwin T. 1984. Tambopata Reserved Zone, Madre de Dios, Peru: history and description of the reserve. Revista Peruana de Entomología 27: 1–8.

Galeano G. 2000. Forest use at the Pacific coast of Chocó, Colombia: a quantitative approach. Economic Botany 54: 358–376.

Gentry A.H. 1988. Changes in plant community diversity and floristic composition on environmental and geographical gradients. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 75: 1–34.

Gilmore M.P., Hardy Eshbaugh W. and Greenberg A.M. 2002. The use, construction, and importance of canoes among the Maijuna of the Peruvian Amazon. Economic Botany 56: 10–26.

Gould K., Howard A.F. and Rodriguez G. 1998. Sustainable production of non-timber forest products: natural dye extraction from El Cruce Dos Aguadas, Peten, Guatemala. Forest Ecology and Management 111: 69–82.

Hanazaki N., Tamashiro J.Y., Leitao Filho H.F. and Begossi A. 2000. Diversity of plant uses in two Caicara communities from the Atlantic Forest coast, Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 9: 597–615.

Harris M. 1964. The Nature of Cultural Things. Random House, New York.

Johnston M. 1998. Tree population studies in low-diversity forests, Guyana. II. Assessments on the distribution and abundance of non-timber forest products. Biodiversity and Conservation 7: 73–86.

Laird S. 2002. Biodiversity and Traditional Knowledge: Equitable Partnerships in Practice. Earthscan, London.

Lamas G. 1994. List of Butterflies from Tambopata (Explorer’s Inn Reserve). In: Barkley L.J. (ed) The Tambopata-Candamo Reserved Zone of Southeastern Perú: A Biological Assessment. Rapid Assessment Program Working Papers 6, Conservation International, Washington, DC, pp. 162–177.

Lawrence A. 1999. Tree-cultivation in upland livelihoods in the Philippines: implications for biodiversity conservation and forest policy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK.

Lawrence A. 2003. No forest without timber? International Forestry Review 5: 3–10.

Lawrence A., Ambrose-Oji B., Lysinge R. and Tako C. 2000. Exploring local values for forest biodiversity on Mount Cameroon. Mountain Research and Development 20: 112–115.

Mahapatra A. and Mitchell C.P. 1997. Sustainable development of non-timber forest products: implication for forest management in India. Forest Ecology and Management 94: 15–29.

Malhi Y., Phillips O.L., Baker T., Almeida S., Frederiksen T., Grace J. et al. 2002. An international network to understand the biomass and dynamics of Amazonian forests (RAINFOR). Journal of Vegetation Science 13: 439–450.

Maxwell S. and Bart C. 1995. Beyond ranking: exploring relative preferences in P/RRA. PLA Notes (IIED, London) 22: 28–34.

Misra M.K. and Dash S.S. 2000. Biomass and energetics of non-timber forest resources in a cluster of tribal villages on the Eastern Ghats of Orissa, India. Biomass and Bioenergy 18: 229–247.

Moerman D.E. 1991. The medicinal flora of native North America: an analysis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 31: 1–42.

Mohit G. and Baghel L.M.S. 2000. Promising partnerships: a socio-economic profile of villages in Sambalpur with reference to NTFP. Wastelands-News 15: 42–47.

Ndoye O., Perez M.R. and Eyebe A. 1998. The markets of non-timber forest products in the humid forest zone of Cameroon. Rural Development Forestry Network 22c: 20–21.

Parker T.A.I., Donahue P. and Schulenberg T. 1994. Birds of the Tambopata Reserve. In: Barkley L.J. (ed) The Tambopata-Candamo Reserved Zone of Southeastern Perú: A Biological Assessment. Rapid Assessment Program Working Papers 6, Conservation International, Washington, DC, pp. 103–124.

Paz y Miño C.G., Balslev H. and Valencia R. 1995. Useful lianas of the Siona-Secoya Indians from Amazonian Ecuador. Economic Botany 49: 269–275.

Pearson D. 1984. The tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of the Tambopata Reserved Zone, Madre de Dios, Peru. Revista Peruana de Entomología 27: 15–24.

Perez M.R. and Byron N. 1999. A methodology to analyze divergent case studies of non-timber forest products and their development potential. Forest Science 45: 1–14.

Peters C.M., Balick M.J., Kahn F. and Anderson A.B. 1989. Oligarchic forests of economic plants in Amazonia: utilization and conservation of an important tropical resource. Conservation Biology 3: 341–349.

Phillips O.L. 1996. Some analytical methods in quantitative ethnobotany. In: Alexiades M. (ed) Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual. Advances in Economic Botany Vol. 10. New York Botanical Garden, New York, pp. 171–198.

Phillips O.L. and Gentry A.H. 1993a. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru. I. Statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Economic Botany 47: 15–32.

Phillips O.L. and Gentry A.H. 1993b. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru. II. Additional hypothesis testing in quantitative ethnobotany. Economic Botany 47: 33–43.

Phillips O.L., Gentry A.H., Reynel C., Wilkin P. and Gálvez-Durand B.C. 1994. Quantitative ethnobotany and Amazonian conservation. Conservation Biology 8: 225–248.

Phillips O.L., Martínez R.V., Vargas P.N., Monteagudo A.L., Zans M.E.C., Sánchez W.G. et al. 2003a. Efficient plot-based floristic assessment of tropical forests. Journal of Tropical Ecology 19: 629–645.

Phillips O.L., Vargas P.N., Monteagudo A.L., Cruz A.P., Zans M.E.C., Sánchez W.G. et al. 2003b. Habitat association among Amazonian tree species: a landscape-scale approach. Journal of Ecology 91: 757–775.

Pike K.L. 1967. Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behaviour. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands.

Piñedo-Vasquez M., Zarin D., Jipp P. and Chota-Inuma J. 1990. Use-values of tree species in a communal forest reserve in northeast Peru. Conservation Biology 4: 405–416.

Pitman N., Terborgh J., Silman M.R. and Núñez V.P. 1999. Tree species distributions in an upper Amazonian forest. Ecology 80: 2651–2661.

Prance G.T., Bale W., Boom B.M. and Carbeuri R.L. 1987. Quantitative ethnobotany and the case for conservation in Amazonia. Conservation Biology 1: 296–310.

Richards M. 1993. The potential of non-timber forest products in sustainable natural forest management in Amazonia. Commonwealth Forestry Review 72: 21–27.

Sheil D., Puri R.K., Basuki I., Van Heist M., Syaefuddin, Rukmiyati, Sardjono M.A. et al. 2002. Exploring biological diversity, environment and local people’s perspectives in forest landscapes. Center for International Forestry Research, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Tuomisto H., Ruokolainen K., Kalliola R., Linna A., Danjoy W. and Rodriguez Z. 1995. Dissecting Amazonian biodiversity. Science 269: 63–66.

van Rijsoort J. 2000. Non-timber Forest Products (NTFPs): Their Role in Sustainable Forest Management in the Tropics. 1. Theme Studies Series: Forests, Forestry and Biological Diversity Support Group, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

Wollenberg E. and Ingles A. 1998. Incomes from the Forest: Methods for the Development and Conservation of Forest Products for Local Communities. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Jakarta, Indonesia.

WongJ., Ambrose-OjiB., LawrenceA., LysingeR. and HealeyJ. 2002. tRanks, counts and scores as a means of quantifying local biodiversity values. ETFRN workshop on participatory monitoring and evaluation of biodiversity; 7–25 January 2002. Website: http://www.etfrn.org/etfrn/workshop/biodiversity/documents.html

Zent S. 1996. Behavioural orientations toward ethnobotanical quantification. In: Alexiades M.N. (ed) Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual. New York Botanical Garden, New York, pp. 199–239.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lawrence, A., Phillips, O.L., Ismodes, A.R. et al. Local values for harvested forest plants in Madre de Dios, Peru: Towards a more contextualised interpretation of quantitative ethnobotanical data. Biodivers Conserv 14, 45–79 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-005-4050-8

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-005-4050-8