Abstract

Objective:

This paper reviews a century of research on creating theoretically meaningful and empirically useful scales of criminal offending and illustrates their strengths and weaknesses.

Methods:

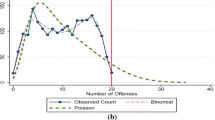

The history of scaling criminal offending is traced in a detailed literature review focusing on the issues of seriousness, unidimensionality, frequency, and additivity of offending. Modern practice in scaling criminal offending is measured using a survey of 130 articles published in five leading criminology journals over a two-year period that included a scale of individual offending as either an independent or dependent variable. Six scaling methods commonly used in contemporary criminological research are demonstrated and assessed using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979: dichotomous, frequency, weighted frequency, variety, summed category, and item response theory ‘theta’.

Results:

The discipline of criminology has seen numerous scaling techniques introduced and forgotten. While no clearly superior method dominates the field today, the most commonly used scaling techniques are dichotomous and frequency scales, both of which are fraught with methodological pitfalls including sensitivity to the least serious offenses.

Conclusions:

Variety scales are the preferred criminal offending scale because they are relatively easy to construct, possess high reliability and validity, and are not compromised by high frequency non-serious crime types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The relationship between Elliott and Ageton’s (1980) sub-scales and their total delinquency frequency scale is not clear. Based on their first table, for whites, the sum of the frequencies of the sub-scales is greater than the total delinquency frequency (49.70 vs. 46.79) whereas for blacks the opposite is true (68.11 vs. 79.20).

In multi-level studies, only the individual level was coded.

Scales of victimization and scales comprised exclusively of substance use were not included.

Crime & Delinquency had the highest proportion of qualifying articles with 69%, followed by Journal of Quantitative Criminology (59%), Justice Quarterly (57%), Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency (48%), and Criminology (46%). According to a Chi-square test, these differences are not statistically significant (p = .16).

As described to the respondents, the 17 items are: purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you; gotten into a physical fight at school or work; taken something from a store without paying for it; other than from a store, taken something not belonging to you worth under $50; other than from a store, taken something not belonging to you worth $50 or more; used force or strong arm methods to get money or things from a person; hit or seriously threatened to hit someone; attacked someone with the idea of seriously hurting or killing them; smoked marijuana or hashish (‘pot,’ ‘grass,’ ‘hash’); used any drugs or chemicals to get high or for kicks, except marijuana; sold marijuana or hashish; sold hard drugs such as heroin, cocaine, or lsd; tried to get something by lying to a person about what you would do for him, that is, tried to con someone; taken a vehicle for a ride or drive without the owner’s permission; broken into a building or vehicle to steal something or just to look around; knowingly sold or held stolen goods; helped in a gambling operation, like running numbers or policy or books.

These responses are coded 0 through 6, respectively, for the summed response category scales.

Conclusions regarding the sensitivity of scales may vary with different model specifications.

Osgood et al. (2002b) recommend using Tobit regression with theta scales. This was explored in the current analysis, but not presented. First, the assumptions of the Tobit model were not met. A Cragg model was more appropriate (Smith and Brame 2003). Second, all of the regression-adjusted differences from logit, negative binomial and Poisson models were easily obtainable from standard ordinary least squares models, so the OLS approach was used for theta scales since they are more suited to OLS than the other scales.

These results are available upon request.

As one reviewer pointed out, in order to use Sellin and Wolfgang’s (1964) scaling method as originally formulated, criminal event data must be used. The weighted frequency scale is evaluated in this paper because this is how Sellin-Wolfgang weights are used in criminological research today. It is possible that an individual-level scale of offending based on summed event seriousness from self-reported criminal events would not exhibit the same problems as the weighted frequency scale. However, to my knowledge, this type of scale has not be attempted in the literature, and there is no reason to expect this scale would dramatically differ from the weighted frequency (but see Wolfgang et al. (1985, 11) for a critique of the related aggregate weighted frequency rate (Blumstein, 1974).

The magnitude of the correlation between variety and frequency of offending is remarkably similar in Monahan and Piquero (2009) and the current study. Calculating the correlation at nine different ages using a contemporary juvenile offender based sample, they obtained estimates ranging from 0.60 to 0.73. This study found the correlation to be 0.66 in a population sample from 1980.

References

Arnold WR (1965) Continuities in research: scaling delinquent offending. Soc Probl 13:59–66

Beccaria C (1764) On crimes and punishment. (trans. H. Paolucci). Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis

Berk R, MacDonald JM (2008) Overdispersion and poisson regression. J Quant Criminol 24:269–284

Blakely CH, Kushler MG, Parisian JA, Davidson WS II (1980) Self-reported delinquency as an evaluation measure: Comparative reliability and validity of alternative weighting schemes. Crim Justice Behav 7:369–386

Blumstein A (1974) Weights in an index of crime. Am Sociol Rev 39:854–864

Blumstein A, Cohen J, Roth J, Visher C (eds) (1986) Criminal careers and “career criminals”, vol 1. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Burt C (1925) The young delinquent. University of London Press, London

Chiricos T, Barrick K, Bales W, Bontrager S (2007) The labeling of convicted felons and its consequences for recidivism. Criminology 45:547–581

Clark WW (1922) Whittier scale for grading juvenile offenses. California Bureau of Juvenile Research, Whittier

Cohen MA (1988) Some new evidence on the seriousness of crime. Criminology 26:343–353

Cohen MA, Rust RT, Steen S, Tidd ST (2004) Willingness-to-pay for crime control programs. Criminology 42:89–110

Dentler RA, Monroe LJ (1961) Social correlates of early adolescent theft. Am Sociol Rev 26:733–743

Durea MA (1933) An experimental study of attitudes toward juvenile delinquency. J Appl Psychol 17:522–534

Elifson KW, Petersen DM, Hadaway CK (1983) Religiosity and delinquency: a contextual analysis. Criminology 21:505–527

Elliott DS (1982) Measuring delinquency (book review). Criminology 20:527–538

Elliott DS, Ageton SS (1980) Self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. Am Sociol Rev 45:95–110

Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS (1985) Explaining delinquency and drug use. Sage, Beverly Hills

Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Menard S (1989) Multiple problem youth: delinquency, substance use, and mental health problems. Springer Verlag, New York

Farrington DP (1973) Self-reports of deviant behavior: predictive and stable? J Crim Law Criminol 64:99–110

Farrington DP, Coid JW, Harnett LM, Jolliffe D, Soteriou N, Turner RE, and West DJ (2006) Criminal careers up to age 50 and life success up to age 48: new findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. 2nd Ed. Home Office Research Study No. 299, London

Francis B, Soothill K, Dittrich R (2001) A new approach for ranking ‘serious’ offences: the use of paired-comparisons methodology. British J Criminol 41:726–737

Frankel MR, McWilliams HA, and Spencer BD (1983) National longitudinal survey of labor force behavior, youth survey (NLS): technical sampling report. NLSY User Services, Columbus, OH

Giordano PC, Longmore MA, Schroeder RD, Seffrin PM (2008) A life-course perspective on spirituality and desistance from crime. Criminology 46:99–132

Gold M (1966) Undetected delinquent behavior. J Res Crim Delinq 13:27–46

Goring C (1913) The english convict. His Majesty’s Printing Office, London

Gorsuch JH (1938) A scale of seriousness of crimes. J Crim Law Criminol 29:245–252

Guttman L (1944) A basis for scaling qualitative data. Am Sociol Rev 9:139–150

Guttman L (1947) The cornell technique for scale and intensity analysis. Educ Psychol Measur 7:247–279

Heckman JT, Ichimura H, Todd P (1998) Matching as an evaluation estimator. Rev Econ Stud 65:261–294

Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, Weis JG (1979) Correlates of delinquency: the illusion of discrepancy between self-report and official measures. Am Sociol Rev 44:995–1014

Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, Weis JG (1981) Measuring delinquency. Sage, Beverly Hills

Hirschi T (1969) Causes of delinquency. University of California Press, Berkeley

Hirschi T, Selvin HC (1967) Delinquency research: an appraisal of analytic methods. The Free Press, New York

Huizinga D, Elliott DS (1986) Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. J Quant Criminol 2:293–327

Jennings WG, Schreck CJ, Sturtz M, Mahoney M (2008) Exploring the scholarly output of academic organization leadership in criminology and criminal justice: a research note on publication productivity. J Crim Justice Education 19:404–416

Kazemian L, Le Blanc M (2007) Differential cost avoidance and successful criminal careers. Random or Rational? Crime Delinq 53:38–63

Kelly DH, Winslow RW (1970) Seriousness of delinquent behavior: an alternative perspective. British J Criminol 10:124–135

King RD, Massoglia M, MacMillan R (2007) The context of marriage and crime: gender, the propensity to marry, and offending in early adulthood. Criminology 45:33–65

Kleck G, Barnes JC (2011) Article productivity among the faculty of criminology and criminal justice doctoral programs, 2005–2009. J Crim Justice Education 22:43–66

Krohn MD, Thornberry TP, Gibson CL, Baldwin JM (2010) The development and impact of self-report measures of crime and delinquency. J Quant Criminol 26:509–525

Kulik JA, Stein KB, Sarbin TR (1968) Dimensions and patterns of adolescent antisocial behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol 32:375–382

Lessieur HR, Lehman PM (1975) Remeasuring delinquency: a replication and critique. British J Criminol 15:69–80

Loftin C, McDowall D (2010) The use of official records to measure crime and delinquency. J Quant Criminol 26:527–532

Lynch JP, Danner MJE (1993) Offense seriousness scaling: an alternative to scenario methods. J Quant Criminol 9:309–322

McIver JP, Carmines EG (1981) Unidimensional scaling. Sage university paper series on quantitative applications in the social sciences, 07–024. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Merton RK (1961) Social problems and sociological theory. In: Merton RK, Nisbet RA (eds) Contemporary social problems: an introduction to the sociology of deviant behavior. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc, New York, pp 697–737

Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA (2001) Sex differences in antisocial behavior: conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Monahan KC, Piquero AR (2009) Investigating the longitudinal relation between offending frequency and offending variety. Crim Justice Behav 36:653–673

Mursell GR (1932) A revision of whittier scale for grading juvenile offenses. Journal of Juvenile Research 3:246–250

Nagin DS (2005) Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nye FI, Short JF Jr (1957) Scaling delinquent behavior. Am Sociol Rev 22:326–331

Orrick EA, Weir H (2011) The most prolific sole and lead authors in elite criminology and criminal justice journals, 2000–2009. J Crim Justice Education 22:24–42

Osgood DW, Schreck CJ (2007) A new method for studying the extent, stability, and predictors of individual specialization in violence. Criminology 45:273–312

Osgood DW, Finken LL, McMorris BJ (2002a) Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance II: tobit regression analysis of transformed scores. J Quant Criminol 18:319–347

Osgood DW, McMorris BJ, Potenza MT (2002b) Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance I: item response theory scaling. J Quant Criminol 18:267–296

Piquero AR, MacIntosh R, Hickman M (2002) The validity of a self-reported delinquency scale: Comparisons across gender, age, race, and place of residence. Sociol Meth Res 30:492–529

Piquero NL, Carmichael S, Piquero AR (2008) Research note: assessing the perceived seriousness of white-collar and street crime. Crime Delinq 54:291–312

Porterfield AL (1943) Delinquency and its outcome in court and college. Am J Sociol 49:199–208

Powers E, Witmer H (1951) An experiment in the prevention of delinquency. The cambridge-somerville youth study. Columbia University Press, New York

Ramchand R, MacDonald JM, Haviland A, Morral AR (2009) A developmental approach for measuring the severity of crimes. J Quant Criminol 25:129–153

Scott JF (1959) Two dimensions of delinquent behavior. Am Sociol Rev 24:240–243

Scott PD (1964) Approved school success rates. British J Criminol 4:525–556

Sellin T, Wolfgang ME (1964) The measurement of delinquency. Patterson Smith, Montclair

Sellin T, Wolfgang ME (1969) Measuring delinquency. In: Sellin T, Wolfgang ME (eds) Delinquency: selected studies. Wiley, New York, pp 1–10

Short JF Jr, Nye FI (1957) Reported behavior as a criterion of deviant behavior. Soc Probl 5:207–213

Slawson J (1926) The delinquent boy. Gorham, Boston

Smith DA, Brame R (2003) Tobit models in social science research: some limitations and a more general alternative. Sociol Meth Res 31:364–388

Sorensen J, Snell C, Rodriguez JJ (2006) An assessment of criminal justice and criminology journal prestige. J Crim Justice Education 17:297–322

Thurstone LL (1927) A law of comparative judgment. Psychol Rev 34:273–286

Tittle CR, Ward DA, Grasmick HG (2003) Self-control and crime/deviance: cognitive vs. behavioral measures. J Quant Criminol 19:333–365

Walker MA (1978) Measuring the seriousness of crimes. British J Criminol 18:348–364

Wanderer JJ (1984) Scaling delinquent careers over time. Criminology 22:83–95

Warr M (1989) What is the perceived seriousness of crimes? Criminology 27:795–821

Weisburd D, Morris NA, Ready J (2008) Risk-focused policing at places: an experimental evaluation. Justice Q 25:163–200

Wellford CF, Wiatrowski M (1975) On the measurement of delinquency. J Crim Law Criminol 66:175–188

Wolfgang ME, Figlio RM, Sellin T (1972) Delinquency in a birth cohort. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wolfgang ME, Figlio RM, Tracy PE, Singer SI (1985) The national survey of crime severity. NCJ-96017. U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC

Wooldridge JM (2009) Introductory econometrics: a modern approach, 4th edn. South-Western, Boston

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Erin Sweeten, Shawn Bushway, Denise Gottfredson, John Laub, Ray Paternoster, Mike Reisig, Scott Decker, the editors of this journal, and three anonymous reviewers for valuable guidance in the development of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sweeten, G. Scaling Criminal Offending. J Quant Criminol 28, 533–557 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9160-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9160-8