Abstract

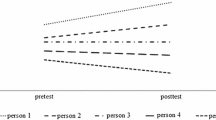

Pascarella (J Coll Stud Dev 47:508–520, 2006) has called for an increase in use of longitudinal data with pretest-posttest design when studying effects on college students. However, such designs that use multiple measures to document change are vulnerable to an important threat to internal validity, regression to the mean. Herein, we discuss a brief history of regression to the mean and illustrate a straightforward procedure to make adjustments to initial pretest scores for regression to the mean effects utilizing a method developed by Roberts (in: G. Echternacht (Guest ed.) New directions for testing and measurement, 1980). Analyses are shown with both unadjusted and adjusted pretest scores, illustrating dramatic differences in conclusions about whether students change across time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Narrative descriptions were adapted from Smart et al. (2000).

References

Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Furby, L. (1973). Interpreting regression toward the mean in developmental research. Developmental Psychology, 8, 172–179.

Galton, F. G. (1886). Regression towards mediocrity in hereditary stature. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 15, 246–263.

Holland, J. L. (1966). The psychology of vocational choice. Waltham, MA: Blaisdell.

Holland, J. L. (1973). Making vocational choices: A theory of careers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Holland, J. L. (1985). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Krause, A., & Pinheiro, J. (2007). Modeling and simulation to adjust p values in presence of a regression to the mean effect. The American Statistician, 61, 302–307.

Linn, R. L. (1980). Discussion: Regression toward the mean and the interval between test administrations. New Directions for Testing and Measurement, 8, 83–89.

Lord, F. M. (1956). The measurement of growth. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 16, 421–437.

Pascarella, E. T. (2006). How college affects students: Ten directions for future research. Journal of College Student Development, 47, 508–520.

Reisner, E. R., Alkin, C., Boruch, R. F., Linn, R. L., & Millman, J. (1982). Assessment of the title I evaluation and reporting system. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Education.

Roberts, A. O. H. (1980). Regression toward the mean and the regression-effect bias. In G. Echternacht (Guest Ed.,) New directions for testing and measurement (Vol. 8, pp. 59–82).

Rogosa, D. (1988). Myths about longitudinal research. In K. W. Schaie, R. T. Campbell, W. Meredity, & S. C. Rawlings (Eds.), Methodological issues in aging research (pp. 171–209). New York: Springer Publishing Co.

Rosen, D., Holmberg, K., & Holland, J. L. (1989). The college majors finder. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Smart, J. C. (2005). Attributes of exemplary research manuscripts employing quantitative analyses. Research in Higher Education, 46, 461–477.

Smart, J. C., Feldman, K. A., & Ethington, C. A. (2000). Academic disciplines: Holland’s theory and the study of college students and faculty. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Tallmadge, G. K. (1982). An empirical assessment of norm-referenced evaluation methodology. Journal of Educational Measurement, 19, 97–112.

Tallmadge, G. K., Wood, C. T., & Gamel, N. N. (1981). User’s guide: ESEA title I evaluation and reporting system (revised). Mountain View, CA: RMC Research Corporation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Salient Attributes of the Six Model Environments from Holland’s Theory

Footnote 1

Investigative environments emphasize analytical or intellectual activities aimed at the creation and use of knowledge. Such environments devote little attention to persuasive, social, and repetitive activities. These behavioral tendencies in investigative environments lead, in turn, to the acquisition of analytical, scientific, and mathematical competencies and to a deficit in persuasive and leadership abilities. People in investigative environments are encouraged to perceive themselves as cautious, critical, complex, curious, independent, precise, rational, and scholarly. Investigative environments reward people for skepticism and persistence in problem solving, documentation of new knowledge, and understanding solutions of common problems. Biology, civil engineering, and mathematics are representative of “consistent” disciplines in investigative environments; pharmacy, economics, and sociology are representative of “inconsistent” disciplines in investigative environments.

Artistic environments emphasize ambiguous, free, and unsystematized activities that involve emotionally expressive interactions with others. These environments devote little attention to explicit, systematic, and ordered activities. These behavioral tendencies in Artistic environments lead, in turn, to the acquisition of innovative and creative competencies––language, art, music, drama, writing––and to a deficit in clerical and business system competencies. People in Artistic environments are encouraged to perceive themselves as having unconventional ideas or manners and possessing aesthetic values. Artistic environments reward people for imagination in literary, artistic, or musical accomplishments. English language and literature and philosophy are representative of “consistent” disciplines in Artistic environments; journalism and drama/theater arts are representative of “inconsistent” disciplines in Artistic environments.

Social environments emphasize activities that involve the mentoring, treating, healing, or teaching of others. These environments devote little attention to explicit, ordered, systematic activities involving materials, tools, or machines. These behavioral tendencies in social environments lead, in turn, to the acquisition of interpersonal competencies and to a deficit in manual and technical competencies. People in social environments are encouraged to perceive themselves as cooperative, empathetic, generous, helpful, idealistic, responsible, tactful, understanding, and having concern for the welfare of others. Social environments reward people for the display of empathy, humanitarianism, sociability, and friendliness. Elementary education and social work are representative of “consistent” disciplines in social environments; nursing is representative of an “inconsistent” discipline in social environments.

Enterprising environments emphasize activities that involve the manipulation of others to attain organizational goals or economic gain. These environments devote little attention to observational, symbolic, and systematic activities. These behavioral tendencies in enterprising environments lead, in turn, to an acquisition of leadership, interpersonal, speaking, and persuasive competencies and to a deficit in scientific competencies. People in enterprising environments are encouraged to perceive themselves as aggressive, ambitious, domineering, energetic, extroverted, optimistic, popular, self-confident, sociable, and talkative. Enterprising environments reward people for the display of initiative in the pursuit of financial or material accomplishments, dominance, and self-confidence. Finance, market, and law are representative of “consistent” disciplines in enterprising environments; business administration and business management are representative of “inconsistent” disciplines in enterprising environments.

Realistic environments emphasize concrete, practical activities and the use of machines, tools, and materials. These behavioral tendencies of realistic environments lead, in turn, to the acquisition of mechanical and technical competencies and to a deficit in human relation skills. People in realistic environments are encouraged to perceive themselves as having practical, productive, and concrete values. Realistic environments reward people for the display of conforming behavior and practical accomplishment. Agriculture and archaeology are examples of realistic majors.

Conventional environments emphasize activities that involve the explicit, ordered, systematic manipulation of data to meet predictable organizational demands or specified standards. The behavioral tendencies in conventional environments lead, in turn, to the acquisition of clerical, computational, and business system competencies necessary to meet precise performance standards and to a deficit in artistic competencies. People in conventional environments are encouraged to perceive themselves as having a conventional outlook and concern for orderliness and routines. Conventional environments reward people for the display of dependability, conformity, and organizational skills. Secretarial science is an example of a conventional major.

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rocconi, L.M., Ethington, C.A. Assessing Longitudinal Change: Adjustment for Regression to the Mean Effects. Res High Educ 50, 368–376 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9119-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9119-x