Abstract

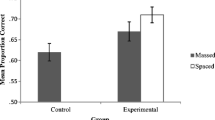

Laboratory studies have demonstrated the long-term memory benefits of studying material in multiple distributed sessions as opposed to one massed session, given an identical amount of overall study time (i.e., the spacing effect). The current study goes beyond the laboratory to investigate whether undergraduates know about the advantage of spaced study, to what extent they use it in their own studying, and what factors might influence its utilization. Results from a web-based survey indicated that participants (n = 285) were aware of the benefits of spaced study and would use a higher level of spacing under ideal compared to realistic circumstances. However, self-reported use of spacing was intermediate, similar to massing and several other study strategies, and ranked well below commonly used strategies such as rereading notes. Several factors were endorsed as important in the decision to distribute study time, including the perceived difficulty of an upcoming exam, the amount of material to learn, how heavily an exam is weighed in the course grade, and the value of the material. Further, level of metacognitive self-regulation and use of elaboration strategies were associated with higher rates of spaced study. Additional research is needed to examine student study habits in a naturalistic setting, and to explore effective ways to encourage behavior change through motivational and teaching techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Given the nature of Likert-type survey data, Friedman’s two-way ANOVA was conducted as a non-parametric equivalent to the repeated-measures ANOVA; this produced results leading to identical conclusions about the lack of meaningful rankings amongst the strategies, x 2(9) = 363.586, p < .001.

A non-parametric Wilcoxon Signed-Ranked Test was also conducted. The results from this test were equivalent to those obtained using the paired-samples t test, Z = −2.512, p = .012.

Non-parametric Spearman correlations were also run on the data leading to identical conclusions except in two cases. Correlations between the elaboration subscale and number of days used to study under ideal and real conditions were found to only approach our conservative level of significance, r(283) = .191, p = .001 and r(283) = .178, p = .003 respectively.

An anonymous reviewer pointed out that several of the strategies (e.g., re-reading notes) could be performed using spacing or massing, which themselves are separate strategies listed in this survey item. This factor may have contributed to our difficulty in establishing meaningful rankings amongst the strategies.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

References

Balch, W. R. (2006). Encouraging distributed study: A classroom experiment on the spacing effect. Teaching of Psychology, 33(4), 249–252.

Benjamin, A., & Bird, R. (2006). Metacognitive control of the spacing of study repetitions. Journal of Memory and Language, 55(1), 126–137. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2006.02.003.

Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 185–205). Cambridge, MA US: The MIT Press. Retrieved from http://bjorklab.psych.ucla.edu.

Callender, A., & McDaniel, M. (2009). The limited benefits of rereading educational texts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.07.001.

Cepeda, N., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354–380. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.354.

Cuddy, L. J., & Jacoby, L. L. (1982). When forgetting helps memory: An analysis of repetition effects. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 21(4), 451–467. Retrieved from http://pao.chadwyck.com.

Dempster, F. N. (1988). The spacing effect: A case study in the failure to apply the results of psychological research. American Psychologist, 43(8), 627–634.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Retrieved from http://www.books.google.com.

Glenberg, A. (1979). Component-levels theory of the effects of spacing of repetitions on recall and recognition. Memory & Cognition, 7(2), 95–112. Retrieved from PsycINFO database.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains. American Psychologist, 53(4), 449–455. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.4.449.

Karpicke, J. D. (2009). Metacognitive control and strategy selection: Deciding to practice retrieval during learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 138(4), 469–486. doi:10.1037/a0017341.

Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17(4), 471–479. doi:10.1080/09658210802647009.

Koriat, A. (1997). Monitoring one’s own knowledge during study: A cue-utilization approach to judgments of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 126(4), 349–370. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.126.4.349.

Kornell, N. (2009). Optimising learning using flashcards: Spacing is more effective than cramming. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 1297–1317. doi:10.1002/acp.1537.

Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2007). The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(2), 219–224. Retrieved from PsycINFO database.

Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2008). Learning concepts and categories: Is spacing the “enemy of induction”? Psychological Science, 19(6), 585–592. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02127.x.

Krug, D., Davis, T. B., & Glover, J. A. (1990). Massed versus distributed repeated reading: A case of forgetting helping recall? Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(2), 366–371. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.2.366.

Matvey, G., Dunlosky, J., & Guttentag, R. (2001). Fluency of retrieval at study affects judgments of learning (JOLs): An analytic or nonanalytic basis for JOLs? Memory and Cognition, 29(2), 222–233. Retrieved from PsycINFO database.

McCabe, J. (2011). Metacognitive awareness of learning strategies in undergraduates. Memory & Cognition, 39(3), 462–476. doi:10.3758/s13421-010-0035-2.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. (1991). A manual for the use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). University of Michigan, National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning, Ann Arbor, MI.

Pyc, M., & Dunlosky, J. (2010). Toward an understanding of students’ allocation of study time: Why do they decide to mass or space their practice? Memory & Cognition, 38(4), 431–440. doi:10.3758/MC.38.4.431.

Roediger, H. L., I. I. I., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x.

Rohrer, D., & Pashler, H. (2007). Increasing retention without increasing study time. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 183–186. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00500.x.

Rohrer, D., & Taylor, K. (2006). The effects of overlearning and distributed practice on the retention of mathematics knowledge. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 1209–1224. doi:10.1002/acp.1266.

Schwarz, N. (1999). Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. American Psychologist, 54(2), 93–105. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.2.93.

Son, L. K. (2004). Spacing one’s study: Evidence for a metacognitive control strategy. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 30(3), 601–604. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.30.3.601.

Son, L. K., & Kornell, N. (2009). Simultaneous decisions at study: Time allocation, ordering, and spacing. Metacognition and Learning, 4(3), 237–248. doi:10.1007/s11409-009-9049-1.

Sperling, R. A., Howard, B. C., Staley, R., & DuBois, N. (2004). Metacognition and self-regulated learning constructs. Educational Research and Evaluation, 10(2), 117–139. doi:10.1076/edre.10.2.117.27905.

Toppino, T., Cohen, M., Davis, M., & Moors, A. (2009). Metacognitive control over the distribution of practice: When is spacing preferred? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(5), 1352–1358. doi:10.1037/a0016371.

Van Etten, S., Freebern, G., & Pressley, M. (1997). College students’ beliefs about exam preparation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22(2), 192–212. doi:10.1006/ceps.1997.0933.

Wolters, C. A. (2003). Regulation of motivation: Evaluating an underemphasized aspect of self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(4), 189–205. doi:10.1207/S15326985EP3804_1.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Goucher College Summer Science Research Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: spacing-related survey items, organized by heading in the results section

Knowledge of spacing effect

-

(1)

Which of the following strategies do you think research has found to be better for long-term retention of material, assuming the total amount of study time is the same?

-

(a)

Studying the material in multiple sessions of shorter duration

-

(b)

Studying the material in one longer session

-

(c)

Both strategies are equally effective

-

(a)

-

(2)

If you had a total of 5 h to study for an upcoming test on Friday, IDEALLY how would you spread out your studying (if it took 1 h to study all of the material)? Please write a whole number in one or more of the spaces below, corresponding to the days leading up to the test. The total number of hours should equal 5.

-

(3)

From past experiences and REALISTICALLY speaking, when you have had 5 h to study for an upcoming test, how have you spread out your studying (if it took 1 h to study all of the material in one sitting)? Please write a whole number in one or more of the spaces below, corresponding to the days leading up to the test. The total number of hours should equal 5.

Self-reported study behaviors

-

(4)

When studying for a test, how often do you use the following strategies? (Scale 1 = “Never,” 3 = “Sometimes,” 5 = “Always”)

-

(k)

Reread notes

-

(l)

Reread textbook

-

(m)

Study all material in one session

-

(n)

Make and use flashcards

-

(o)

Reference material to myself

-

(p)

Do practice problems

-

(q)

Make outlines or study guides

-

(r)

Use mnemonic devices

-

(s)

Distribute studying over multiple sessions

-

(t)

Self-test (practice recalling material)

-

(k)

Factors in spacing versus massing

-

(5)

When studying for a DIFFICULT test, do you change the way you study compared to how you would study for a test of average difficulty?

-

(d)

Yes, I spread out my studying more in the days before the test.

-

(e)

Yes, I do all of my studying in only one session.

-

(f)

No, I study the same way for tests of all difficulty levels.

-

(d)

-

(6)

When studying for an EASY test, do you change the way you study compared to how you would study for a test of average difficulty?

-

(g)

Yes, I spread out my studying more in the days before the test.

-

(h)

Yes, I do all of my studying in only one session.

-

(i)

No, I study the same way for tests of all difficulty levels.

-

(g)

-

(7)

After reading each comparison, please indicate on the scale whether you are more or less likely to spread out your studying over a few sessions. (Scale: 1 = “Much more likely to spread out studying,” 3 = “Both strategies are equally likely,” 5 = “Much more likely to study in only one session”)

-

(a)

Upcoming test is multiple-choice (rather than short-answer or essay).

-

(b)

There is a high value of material for future courses or career (rather than a low value).

-

(c)

I have many other academic commitments the same week as the test (rather than few other academic commitments).

-

(d)

I have social commitments the same week as the test (rather than no social commitments).

-

(e)

I have high confidence in my ability to learn the material (rather than low confidence).

-

(f)

The material is interesting to me (rather than the material is not interesting).

-

(g)

The test is weighed heavily in determining the final course grade (rather than the test is not weighed heavily).

-

(h)

There is a lot of material to learn (rather than a little material).

-

(a)

Appendix B: survey items from the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ), Metacognitive Self-Regulation and Elaboration Subscales (Pintrich et al. 1991)

Instructions

The following questions ask about your learning strategies and study skills for recent or current college classes. There are no right or wrong answers. Answer the questions about how you study in classes as accurately as possible. If you think the statement is very true of you, click the last button; if a statement is not true at all of you, click the first button. If the statement is more or less true of you, find the button in between that best describes you. (Scale: 1 = “Not at all true of me,” 7 = “Very true of me”)

Metacognitive self-regulation subscale items

-

(a)

During class time I often miss important points because I’m thinking of other things.

-

(b)

When reading material for courses, I make up questions to help focus my reading.

-

(c)

When I become confused about something I’m reading, I go back and try to figure it out.

-

(d)

If course readings are difficult to understand, I change the way I read the material.

-

(e)

Before I study new course material thoroughly, I often skim it to see how it is organized.

-

(f)

I ask myself questions to make sure I understand the material I have been studying.

-

(g)

I try to change the way I study in order to fit course requirements and the instructor’s teaching style.

-

(h)

I often find that I have been reading but don’t know what it was all about.

-

(i)

I try to think through a topic and decide what I am supposed to learn from it rather than just reading it over when studying.

-

(j)

When studying I try to determine which concepts I don’t understand well.

-

(k)

When I study I set goals for myself in order to direct my activities in each study period.

-

(l)

If I get confused taking notes in class, I make sure I sort it out afterwards.

Elaboration subscale items

-

(a)

When I study for class, I pull together information from different sources, such as lectures, readings, and discussions.

-

(b)

I try to relate ideas from one course to those in other courses whenever possible.

-

(c)

When reading material, I try to relate it to what I already know.

-

(d)

When I study I write brief summaries of the main ideas from the readings and my class notes.

-

(e)

I try to understand material by making connections between readings and concepts from lectures.

-

(f)

I try to apply ideas from course readings in other class activities such as lecture and discussion.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Susser, J.A., McCabe, J. From the lab to the dorm room: metacognitive awareness and use of spaced study. Instr Sci 41, 345–363 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-012-9231-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-012-9231-8