Abstract

Background

Rural areas have historically struggled with shortages of healthcare providers; however, advanced communication technologies have transformed rural healthcare, and practice in underserved areas has been recognized as a policy priority. This systematic review aims to assess reasons for current providers’ geographic choices and the success of training programs aimed at increasing rural provider recruitment.

Methods

This systematic review (PROSPERO: CRD42015025403) searched seven databases for published and gray literature on the current cohort of US rural healthcare practitioners (2005 to March 2017). Two reviewers independently screened citations for inclusion; one reviewer extracted data and assessed risk of bias, with a senior systematic reviewer checking the data; quality of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Results

Of 7276 screened citations, we identified 31 studies exploring reasons for geographic choices and 24 studies documenting the impact of training programs. Growing up in a rural community is a key determinant and is consistently associated with choosing rural practice. Most existing studies assess physicians, and only a few are based on multivariate analyses that take competing and potentially correlated predictors into account. The success rate of placing providers-in-training in rural practice after graduation, on average, is 44% (range 20–84%; N = 31 programs). We did not identify program characteristics that are consistently associated with program success. Data are primarily based on rural tracks for medical residents.

Discussion

The review provides insight into the relative importance of demographic characteristics and motivational factors in determining which providers should be targeted to maximize return on recruitment efforts. Existing programs exposing students to rural practice during their training are promising but require further refining. Public policy must include a specific focus on the trajectory of the healthcare workforce and must consider alternative models of healthcare delivery that promote a more diverse, interdisciplinary combination of providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

One fifth of the United States (US) population resides outside metropolitan areas. Patients in these geographically dispersed areas often have to travel great distances to access healthcare and can experience delays in treatment. Rural communities struggle with recruiting as well as retaining healthcare providers, and report provider shortages with ongoing, long-term vacancies.1,2,3, – 4 While estimates differ by provider group, researchers have found that less than 12% of US physicians practice in rural areas.5 Hence, while one fifth of the nation’s population resides outside metropolitan areas, only about a tenth of the nation’s physicians are found there.

Rural healthcare undoubtedly requires a particular skill set; for example, healthcare providers are asked to treat a diversity of illnesses within their communities and to perform a wide variety of procedures, often without specialized training.6,7,8,9,10, – 11 However, in recent years, strategies have been implemented at the regional, state, and federal levels to increase the number of providers practicing in rural healthcare.12,13,14, – 15 In addition, the care environment has changed in the last decade as a result of the increased use of internet applications and advanced communication technologies.16 Telehealth has expanded patient access to care and offers new possibilities for supporting rural healthcare providers, such as access to specialist input through online real-time exchanges and high-quality videoconferencing technology. A comprehensive analysis of 1988 to 1997 graduates suggested that a physician’s hometown was a significant predictor of practice in rural settings.17 However, insight is needed into why providers are currently choosing to practice in remote areas, particularly as older analyses may be outdated with respect to the care environment, and research has not been summarized in a comprehensive review across existing studies.18 Information on the relative importance of demographic characteristics and motivational factors may provide guidance as to which groups of providers should be targeted to maximize return on recruitment efforts to ameliorate shortages.

Finding ways to encourage physicians to practice in underserved areas has been an ongoing priority for organizations such as the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). In 2006, AAMC called for a 30% increase in MD-granting medical school enrollment by 2015.19 A systematic review with literature searches to 2006 highlighted efforts to target healthcare providers in training—for example, by adding rural tracks to medical school programs.20 Since publication of the review, a substantial number of new studies have been published. In addition, the impact of programs and reforms implemented to address shortcomings in rural healthcare provision, such as service-requiring scholarships or loan repayment programs, should have become apparent by now.12 , 14 , 15

The purpose of this review is to assess and synthesize the evidence for geographic practice choice and effects of training programs on healthcare providers practicing in rural healthcare settings in the US.

METHODS

This work is part of a larger project commissioned by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for use in developing policy recommendations regarding rural VA care.21 The systematic review was supported by a technical expert panel (TEP) and is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42015025403) and followed PRISMA guidelines.22 Two independent reviewers assessed citations for inclusion; discrepancies were reconciled through discussion.

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsycINFO, ERIC [Education Resources Information Center], WorldCat, and the Grey Literature Report for English-language articles published from 2005 to March 2017. Search terms included “rural” and synonyms (e.g. “non-urban”), healthcare personnel terms, and factors related to “choice” and “training” (see Appendix). We supplemented the search with references mined from pertinent reviews, targeted online resources, and consulted with experts.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants

Based on TEP input, we concentrated on healthcare providers with long training periods that require workforce planning and that are critical for rural community-based outpatient clinics, rural health clinics, and Critical Access Hospitals (family, internal, and emergency medicine physicians; obstetrician/gynecologists, general surgeons, pediatricians, geriatricians, psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants). Exposure/Training: We included studies of provider-reported or analytically derived factors potentially associated with geographic choices for practicing in rural care. To assess the success of training, we included studies evaluating the educational programs specific to rural healthcare and programs explicitly aimed at increasing provider recruitment for rural areas. Study design: Studies with or without concurrent or historic comparators were eligible. Provider choice studies could report qualitative or quantitative data; training program evaluations had to report numerical data (i.e., a rate). Outcome: Studies had to report on practicing in rural care to be eligible. Studies assessing only the intent to practice in rural care were not eligible. Timing: Studies reporting on practicing in rural care from 2005 onward were eligible, regardless of the timing of the predictor variables (e.g., growing up in a rural area), evaluation period, exposure duration, or length of follow-up. Setting: Studies had to report on rural (as defined by the author) US healthcare settings to be eligible.

Data Abstraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

One reviewer extracted data, and an experienced systematic reviewer checked the entries. With the help of the TEP, we selected the categories provider characteristics, training, financial aspects, and setting characteristics to differentiate factors potentially influencing geographic practice location. For training program evaluations, we abstracted recruitment success and retention. Publications reporting on the same participants were summarized as one study and counted only once.

We assessed risk of bias for the outcome of interest. Critical appraisal concentrated on the representativeness of the sample (selection bias), the response or follow-up rate (attrition bias), the role of confounding variables (e.g., lack of multivariate analyses), and the data source reporting and reliability (detection bias).4

Synthesis and Quality of Evidence Assessment

For practice choice location data, we presented the presence as well as the absence of associations for all variables of interest that had been analyzed in included studies. We calculated mean, median, mode, and the range of the proportion of providers in training that practiced in rural environments.

The assessment of evidence quality across all identified studies included study limitations, inconsistency in results across studies, imprecision (e.g., due to lack of reported effect sizes), and the magnitude of effect.21 Since provider choice factors cannot be analyzed in experimental studies, we did not set the GRADE starting point at low quality of evidence, but considered multivariate analyses to be moderate quality of evidence. We differentiated high, moderate, low, and very low quality of evidence to describe our confidence in the findings among studies.

RESULTS

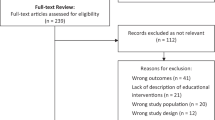

Our literature searches identified 7276 citations. Of these, 510 were obtained as full text. The Appendix shows the literature flow diagram and the reasons for exclusion. In total, 50 studies (reported in 64 publications) met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 31 reported predictors of providers’ geographic choices, and 24 studies reported on the success of healthcare provider training programs. Risk of selection bias was rated high in 34% of studies due to the lack of evaluating a representative sample for the population of interest. Risk of attrition bias was rated high in 22% of studies, usually due to a low response rate across eligible participants. Risk of bias due to confounding variables (e.g., through lack of control of competing or correlated variables) was rated high in 36% of studies. All included studies are documented in detail in the evidence table and the risk of bias table in the Appendix.

Factors Influencing Healthcare Providers’ Geographic Choices for Practice

The 31 identified studies used surveys, qualitative analyses of interviews, or existing data sets to identify predictors for practicing in rural healthcare. Physicians were the focus in most studies, with the remaining addressing physician assistants or a range of healthcare providers. The study samples ranged in number from eight participants, to data sets comprising 322,13123 healthcare providers. Most studies defined rurality based on existing coding schemes such as the Rural–Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC).

Table 1 documents factors associated with the choice of practice location identified across studies and the quality of evidence for each finding.

Provider Characteristics

Twenty-two studies were identified that addressed the rural background of providers, and overwhelmingly showed a positive association with the choice to practice in a rural area. This association was also demonstrated in multivariate analyses controlling for competing variables such as rural health track exposure. Effect estimates ranged from an odds ratio (OR) of 4.02 (CI 2.17–7.74)24 in a sample of West Virginia medical graduates to an OR of 2.80 (CI 2.09–3.74)27 based on an analysis of 30 years of training rural physicians in Michigan. Given the substantial amount of research, confirmation in multiple multivariate analyses by independent author groups, and the large effect, we determined the quality of evidence to be high. We found moderate-quality evidence for a lack of association with age or race: studies that assessed this feature consistency found no association, including multivariate analyses controlling for confounders. Two studies reported on the effect of exposure to rural areas not specific to childhood experiences or provider training (N = 22, qualitative interviews; N = 197, survey response rate = 67%),34 , 56 and both suggested a positive association (low quality of evidence due to study limitations and the absence of effect size estimates). Other provider characteristics such as gender, the role of family, marital status, and international medical graduate status were also addressed in several publications, but the results reported were conflicting.

Training

We identified 15 studies that assessed the effect of rural experience, tracks, or rotations as part of healthcare provider education or training. The largest effect size in a multivariate analysis with a substantial sample size was noted for physicians attending a rural campus in Kentucky (N = 31,120, adjusted OR 5.46, CI 2.32–3.69).47 An association was confirmed in other multivariate analyses,27 , 52 including a study reporting an association after adjusting for rural upbringing,25 lending support for the importance of training. However, other analytical studies and interview data indicated that rural training was not particularly influential in provider practice choice.40 Primary care and family medicine focus were addressed in three studies and were associated with greater odds of practicing in rural care. The largest study (N = 322,131; follow-up rate = 98%) reported that a career in family medicine (adjusted OR 2.65; 95% CI 2.51–2.79) or primary care (adjusted OR 1.06; 95% CI 1.01–1.11) was associated with rural practice.23 We determined the quality of evidence supporting the effect of training efforts and the predictive value of primary care focus to be moderate. Two studies (N = 175,649; N = 231,660) demonstrated that osteopathic (vs. allopathic) physicians contribute proportionally more to rural healthcare, but the quality of evidence was rated low because the statistical significance of this difference was not reported and confounding factors were not addressed.45 , 50

Financial Aspects

As documented in Table 1, results were mixed regarding the influence of student loans, student debt amount, or participation in scholarship programs (addressed in nine studies) and the importance of salary (addressed in five studies). Both areas were rated as very low quality, because it was not possible to determine whether these aspects were important determinants of practicing in rural healthcare.

Setting Characteristics

Six studies addressed the scope of practice, and while some studies highlighted the broad scope as the reason for choosing rural practice, others indicated that this was important for only a small proportion of providers. Four studies assessed the influence of recreational activities that rural areas offered, but results were inconsistent within and across studies, depending on the individual predictor. Both areas were rated as having very low-quality evidence, because it cannot be determined whether these characteristics are a significant factor for geographic practice choice. Finally, lifestyle in rural communities was investigated in two studies (N = 8, qualitative interviews; N = 197, survey response rate = 67%), both reporting an influence on choice of practice location.34 , 41 The quality of evidence was rated low due to study limitations.

Training-Based Interventions to Increase Rural Healthcare Provider Recruitment and Retention

We identified 24 studies evaluating rural healthcare professional student and resident training. Most studies evaluated training programs at a single institution (71%), with reported capacity of two to four trainees per year. Seven studies reported on data across multiple training institutions, including an evaluation of 18 medical school rural track programs that were able to document their students’ practice locations (follow-up rate = 60%).57 Forty-six percent of the included studies evaluated medical students, and another 46% evaluated medical resident training, most frequently for family medicine residents. One study each assessed nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Study sample size varied widely, with some reporting on a handful of recent graduates and others with data sets evaluating decades of experience with rural training.27 The studies utilized internal records, surveys, or the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile for determining practice locations after graduation. Twenty-nine percent of identified studies did not report how “rural” was defined. The majority of training programs consisted of embedding a student or trainee in a rural community for part (or all) of their clinical training, ranging in duration from 4 weeks to 5 years.58 In some cases, programs sought to preferentially enroll trainees with an established interest in rural care.59

Across studies reporting the proportion of trainees choosing rural practice, success rates varied widely, ranging from 20 to 86%.57 , 60 However, as Figure 1 demonstrates, the large majority of results were in the range of 30 to 65%; the mean was 44% (median 41%). The figure incorporates data from 31 programs reported across 18 studies.

Given the substantial variation across programs, we explored potential sources of heterogeneity. The rural track programs aimed at medical residents reported a mean success rate of 44% for recruitment into rural practice and did not differ from other programs. Only a small proportion of studies explicitly reported a targeted effort by the school in selecting students with an affinity for rural practice (e.g., preferred access for rural-based students). There was a trend toward higher success rates for programs with longer rural exposure, but we did not detect a systematic effect. Studies that reported on retention of trainees in rural areas indicated that more than half of study participants practiced in the rural areas where they were trained, but data were sparse.61 , 62

Based on the variation in estimates and the frequent presence of selection bias, we conclude that there is moderate-quality evidence that the success rate of rural training programs ranges from 30 to 65%, and, on average, only one in two trainees is likely to enter rural care.

DISCUSSION

The principal findings of our review are that growing up in a rural location remains the strongest predictor of choosing a rural practice location, but evidence determining the relative importance of factors is often lacking, and while rural-specific training tracks have some success in rural practice recruitment, the factors contributing to effectiveness are poorly understood.

Understanding the factors influencing providers to practice in a rural location is critical for informing strategies to increase the number of rural providers. Growing up in a rural area remains the strongest predictor and is consistently associated with practicing in a rural community. This aspect has been reported in prior decades, and it appears that it remains a critical factor in today’s rural healthcare environment.17 The fact that 30 to 52% of providers from rural backgrounds reported entering rural practice is promising.25 , 30 Rural recruitment will benefit from further investigation into the specific experiences and characteristics of rural upbringing that increase the likelihood of choosing rural practice. Other factors associated with rural practice were the effect of rural training programs and a primary care and family medicine focus. We did not replicate associations with provider race or the importance of loan forgiveness programs, as suggested in previous predictions for underserved areas in the US.63 Multivariate analyses did not detect an effect of race on choosing rural healthcare, and while some of the studies found a correlation with medical school loan repayment,32 self-reports from practicing providers did not indicate particular importance; for example, some participants noted that they were already practicing in rural areas when they were made aware of loan forgiveness programs.40 The result could be due in part to social desirability effects; however, the relative importance across all considerations influencing the decision to practice in a rural community is simply not known. We note that despite the large number of studies providing data on associations, studies evaluating the relative importance of individual competing and potentially correlated factors, i.e. through multivariate analyses, are scarce.

We identified a substantial number of rural training program evaluations; however, these also mostly addressed medical students and residents. Across all approaches, about 30 to 65% of students exposed to rural-focused training enter these settings. Success rates have not increased based on comparison to a prior review with data to 2006 that reported a success rate of 53 to 64%.64 Individual training programs varied widely in format and duration. However, we did not identify factors that systematically and statistically significantly affected success rates, and conclude that the specific aspects of the training experience that influence success need further investigation.

We showed that rural upbringing continues to be a critical aspect, and some training programs specifically select applicants based on their affinity with rural areas. That these providers may constitute less than 1% of the total workforce23 has policy implications for the preferential recruitment of students and providers-in-training from rural backgrounds. A recent overview addressing determinants of an urban-origin student choosing rural practice highlighted that barriers to a rural career included lack of opportunities for spouses/partners, children, and continuing medical education.65 Accordingly, Deutsch et al. advised: “don’t select medical students—convince them.”66 In addition, greater efforts are needed to retain healthcare providers in rural care.21 , 67

Our review has several limitations. Among included providers, non-physicians were underrepresented, and we did not address provider satisfaction with rural training programs.68 , 69 There were study limitations such as social desirability effects in interviews determining choice of practice, potential for publication bias and inherent confounding, with training institutions being more motivated to highlight program successes and to publish data on rural placement. Furthermore, the selection of a rural training track is likely to be influenced by an affinity with rural regions, and the success of rural training programs cannot be attributed exclusively to the educational program.70 In addition, the definition of rural was operationalized differently across studies, adding heterogeneity. Overall, the conclusions of our review are limited by a relative absence of evidence for many provider types and by limited quality of evidence.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

This review provides insight into the relative importance of demographic characteristics and motivational factors in determining which groups of providers should be targeted to maximize return on recruitment efforts. Growing up in a rural area remains the strongest predictor of future practice in a rural area, but the number of such students is currently too small for this to be the primary policy option for alleviating rural practice shortages, and studies investigating confounding factors are sparse. Exposing medical students and residents to rural practice during their training is a promising approach for increasing rural healthcare recruiting, but requires further refining and may need to be augmented by recruiting a greater number of prospective students from rural areas. Introducing more healthcare provider students to rural practice is a potentially promising intervention; however, existing programs report limited success, given that half of the exposed students do not chose rural care, and we lack information on variables associated with more successful programs.

Public policy must include a specific focus on the trajectory of the healthcare workforce under continued traditional approaches. It is well established that an adequate supply of healthcare workforce does not, and will not, meet the demand to ensure a healthy population in current or future rural settings. Alternative models of healthcare delivery that promote a more diverse, interdisciplinary combination of providers, educated through a variety of modes, must be seriously considered. Debate should include the financing model for health professional education and health workforce programs, as well as the ability to demonstrate longitudinal value or return on investment on the patchwork of health workforce programs. A national framework for focusing health workforce development at all levels of the educational system and aligning academic, public, and private health workforce investment is critical. A closer, more realistic analysis of the effect of immigration policies, curriculum and training modes for all levels of healthcare staff, and the integration of healthcare technology into the training, education, and support of rural practitioners offers a greater opportunity to mount an adequate response to the current and future crisis.

References

MacDowell M, Glasser M, Fitts M, Fratzke M, Peters K. Perspectives on rural health workforce issues: Illinois-Arkansas comparison. J Rural Health. 2009;25(2):135–40.

MacDowell M, Glasser M, Fitts M, Nielsen K, Hunsaker M. A national view of rural health workforce issues in the USA. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1531.

Doty B, Zuckerman R, Finlayson S, Jenkins P, Rieb N, Heneghan S. General surgery at rural hospitals: a national survey of rural hospital administrators. Surgery. 2008;143(5):599-606.

Weinhold I, Gurtner S. Understanding shortages of sufficient health care in rural areas. Health Policy. 2014;118(2):201-14.

Rosenblatt RA, Chen FM, Lishner DM, Doescher MP. The Future of Family Medicine and Implications for Rural Primary Care Physician Supply. Final Report #125, August 2010. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington School of Medicine Department of Family Medicine., 2010.

Deveney K, Hunter J. Education for rural surgical practice: the Oregon Health & Science University model. Surg Clin N Am. 2009;89(6):1303-8, viii.

Henry LR, Hooker RS, Yates KL. The role of physician assistants in rural health care: a systematic review of the literature. J Rural Health. 2011;27(2):220-9.

Baker E, Schmitz D, Epperly T, Nukui A, Miller CM. Rural Idaho family physicians’ scope of practice. J Rural Health. 2010;26(1):85-9.

Getson DS. Rural practice realities. W V Med J. 2013;109(4):34-7.

Chipp C, Dewane S, Brems C, Johnson ME, Warner TD, Roberts LW. “If only someone had told me...”: lessons from rural providers. J Rural Health. 2011;27(1):122-30.

Weigel PA, Ullrich F, Shane DM, Mueller KJ. Variation in primary care service patterns by rural-urban location. J Rural Health. 2016;32(2):196-203.

Pathman DE. What outcomes should we expect from programs that pay physicians’ training expenses in exchange for service? N C Med J. 2006;67(1):77-82.

Seligson RW, Highsmith PP. North Carolina Medical Society Foundation’s Community Practitioner Program. N C Med J. 2006;67(1):83-5.

Chen C, Xierali I, Piwnica-Worms K, Phillips R. The redistribution of graduate medical education positions in 2005 failed to boost primary care or rural training. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2013;32(1):102-10.

Dorsey ER, Nicholson S, Frist WH. Commentary: improving the supply and distribution of primary care physicians. Acad Med. 2011;86(5):541-3.

Fortney JC, Burgess JF, Jr., Bosworth HB, Booth BM, Kaboli PJ. A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26 Suppl 2:639-47.

Wade ME, Brokaw JJ, Zollinger TW, Wilson JS, Springer JR, Deal DW, et al. Influence of hometown on family physicians’ choice to practice in rural settings. Fam Med. 2007;39(4):248-54.

Lindsay S. Gender differences in rural and urban practice location among mid-level health care providers. J Rural Health. 2007;23(1):72-6.

Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC Statement on the Physician Workforce, 2006. 2006.

Myers MA, Reed KD. The virtual ICU (vICU): a new dimension for critical care nursing practice. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;20(4):435-9.

Hempel S, Gibbons MM, Ulloa JG, Macqueen IT, Miake-Lye IM, Beroes JM, et al. Rural Healthcare Workforce: A Systematic Review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington (DC); 2015.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-12.

Phillips RL, Dodoo MS, Petterson S, Xierali I, Bazemore A, Teevan B, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student & resident choices? March 2, 2009. Washington, DC: The Robert Graham Center., 2009.

Shannon CK, Jackson J. Validity of medical student questionnaire data in prediction of rural practice choice and its association with service orientation. J Rural Health. 2015;31(4):373-81.

Zink T, Center B, Finstad D, Boulger JG, Repesh LA, Westra R, et al. Efforts to graduate more primary care physicians and physicians who will practice in rural areas: examining outcomes from the university of Minnesota-Duluth and the rural physician associate program. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):599-604.

Whitacre BE, Pace V, Hackler JB, Janey M, Landgraf CE, Pettit WJ. An evaluation of osteopathic school programs designed to promote rural location by graduates. Int J Osteopath Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

Wendling AL, Phillips J, Short W, Fahey C, Mavis B. Thirty years training rural physicians: outcomes from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine Rural Physician Program. Acad Med. 2016;91(1):113-9.

Shannon CK, Jackson J. A study of predictive validity of physician assistant students’ reported practice site intent. J Physician Assist Educ. 2011;22(3):29-32.

Pepper CM, Sandefer RH, Gray MJ. Recruiting and retaining physicians in very rural areas. J Rural Health. 2010;26(2):196-200.

Jarman BT, Cogbill TH, Mathiason MA, O’Heron CT, Foley EF, Martin RF, et al. Factors correlated with surgery resident choice to practice general surgery in a rural area. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(6):319-24.

Smith B, Muma RD, Burks L, Lavoie MM. Factors that influence physician assistant choice of practice location. JAAPA. 2012;25(3):46-51.

Duffrin C, Diaz S, Cashion M, Watson R, Cummings D, Jackson N. Factors associated with placement of rural primary care physicians in North Carolina. South Med J. 2014;107(11):728-33.

Hancock C, Steinbach A, Nesbitt TS, Adler SR, Auerswald CL. Why doctors choose small towns: a developmental model of rural physician recruitment and retention. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2009;69(9):1368–76.

Helland LC, Westfall JM, Camargo CA Jr., Rogers J, Ginde AA. Motivations and barriers for recruitment of new emergency medicine residency graduates to rural emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):668-73.

Schiff T, Felsing-Watkins J, Small C, Takayesu A, Withy K. Addressing the physician shortage in Hawai’i: recruiting medical students who meet the needs of Hawai’i’s rural communities. Hawai’i J Med Public Health. 2012;71(4 Suppl 1):21-5.

Kimball EB, Crouse BJ. Perspectives of female physicians practicing in rural Wisconsin. WMJ. 2007;106(5):256-9.

Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Santana AJ. The relationship between entering medical students’ backgrounds and career plans and their rural practice outcomes three decades later. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):493-7.

Renner DM, Westfall JM, Wilroy LA, Ginde AA. The influence of loan repayment on rural healthcare provider recruitment and retention in Colorado. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(4):1605.

Fernandez-Granero MA, Sanchez-Morillo D, Leon-Jimenez A. Computerised analysis of telemonitored respiratory sounds for predicting acute exacerbations of COPD. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2015;15(10):26978–96.

Diemer D, Leafman J, Nehrenz GM Sr., Larsen HS. Factors that influence physician assistant program graduates to choose rural medicine practice. J Physician Assist Educ. 2012;23(1):28-32.

Henry LR, Hooker RS. Retention of physician assistants in rural health clinics. J Rural Health. 2007;23(3):207-14.

Stenger J, Cashman SB, Savageau JA. The primary care physician workforce in Massachusetts: implications for the workforce in rural, small town America. J Rural Health. 2008;24(4):375-83.

Glasser M, MacDowell M, Hunsaker M, Salafsky S, Nielsen K, Peters K, et al. Factors and outcomes in primary care physician retention in rural areas. 2010.

Phillips J, Hustedde C, Bjorkman S, Prasad R, Sola O, Wendling A, et al. Rural Women Family Physicians: strategies for successful work-life balance. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(3):244-51.

Chen F, Fordyce M, Andes S, Hart LG. Which medical schools produce rural physicians? A 15-year update. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):594-8.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physician supply and demand: Projections to 2020. 2006.

Crump WJ, Fricker RS, Ziegler CH, Wiegman DL. Increasing the Rural Physician Workforce: A Potential Role for Small Rural Medical School Campuses. J Rural Health. 2016;32(3):254-9.

Mason PB, Cossman JS. Does one medical school’s admission policy help a rural state “grow their own” physicians? J Miss State Med Assoc. 2012;53(9):284-6, 8-92.

Mertz E, Jain R, Breckler J, Chen E, Grumbach K. Foreign versus domestic education of physicians for the United States: a case study of physicians of South Asian ethnicity in California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4):984-93.

Fordyce MA, Doescher MP, Chen FM, Hart LG. Osteopathic physicians and international medical graduates in the rural primary care physician workforce. Fam Med. 2012;44(6):396-403.

Terhune KP, Zaydfudim V, Abumrad NN. International medical graduates in general surgery: increasing needs, decreasing numbers. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):990-6.

Petrany SM, Gress T. Comparison of academic and practice outcomes of rural and traditional track graduates of a family medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):819-23.

Ziegler C. The association of medical student debt on choice of primary care specialty and rural practice location 2015.

Snyder J, Nehrenz G, Danielsen R, Pedersen D. Educational debt: does it have an influence on initial job location and specialty choice? J Physician Assist Educ. 2014;25(4):39-42.

Heneghan SJ, Bordley Jt, Dietz PA, Gold MS, Jenkins PL, Zuckerman RJ. Comparison of urban and rural general surgeons: motivations for practice location, practice patterns, and education requirements. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(5):732-6.

McKinstry B, Watson P, Pinnock H, Heaney D, Sheikh A. Confidentiality and the telephone in family practice: a qualitative study of the views of patients, clinicians and administrative staff. Fam Pract. 2009;26(5):344-50.

Deutchman M. Medical School Rural Tracks in the US. Policy brief: 2013. Washington, DC: National Rural Health Association; 2013.

Antonenko DR. Rural surgery: the North Dakota experience. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89(6):1367-72, x.

Rabinowitz HK, Petterson SM, Boulger JG, Hunsaker ML, Markham FW, Diamond JJ, et al. Comprehensive medical school rural programs produce rural family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(12):1350.

Nash LR, Olson MM, Caskey JW, Thompson BL. Outcomes of a Texas family medicine residency rural training track: 2000 through 2007. Tex Med. 2008;104(9):59-63.

Ross R. Fifteen-year outcomes of a rural residency: aligning policy with national needs. Fam Med. 2013;45(2):122-7.

Patterson DG, Longenecker R, Schmitz D, Phillips RL, Skillman SM, Doescher MP. 2013 Policy Brief: Rural Residency Training for Family Medicine Physicians: Graduate Early-Career Outcomes, 2008–2012: Rural Training Track, technical assistance program; 2013 [8/20/2015].

Goodfellow A, Ulloa JG, Dowling PT, Talamantes E, Chheda S, Bone C, et al. Predictors of primary care physician practice location in underserved urban or rural areas in the United States: a systematic literature review. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1313-21.

Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: a systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):235-43.

Myhre DL, Bajaj S, Jackson W. Determinants of an urban origin student choosing rural practice: a scoping review. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(3):3483.

Deutsch T, Honigschmid P, Wippermann U, Frese T, Sandholzer H. Don’t select medical students--convince them. CMAJ. 2011;183(17):2017.

Scarbrough AW, Moore M, Shelton SR, Knox RJ. Improving primary care retention in medically underserved areas what’s a clinic to do? Health Care Manager. 2016;35(4):368-72.

Toner JA, Ferguson KD, Sokal RD. Continuing interprofessional education in geriatrics and gerontology in medically underserved areas. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29(3):157-60.

Tumosa N, Horvath KJ, Huh T, Livote EE, Howe JL, Jones LI, et al. Health care workforce development in rural America: when geriatrics expertise is 100 miles away. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2012;33(2):133-51.

Farmer J, Kenny A, McKinstry C, Huysmans RD. A scoping review of the association between rural medical education and rural practice location. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:27.

Prior presentations

This manuscript is based in part on a 2015 comprehensive evidence synthesis report commissioned by the Department of Veterans Affairs addressing the evidence base for a range of workforce issues.21 The results of the 2015 evidence report were presented to VA leadership and interested staff in a VA Cyber Seminar “Spotlight on Evidence-based Synthesis Program Series” in July 2016.

Funding

The data are in part based on a systematic review funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. The Department of Veterans Affairs had no role in the conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of journal manuscripts; or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors would like to thank the members of our technical expert panel: Nancy Maher, PhD, Program Analyst, Office of Rural Health, VHA Office of Rural Health; Stephanie Kondrick, VHA National Workforce Planner, Healthcare Talent Management Office; Ray Lash, MD, Director, ORH Rural Health Training Initiative, VA Maine Healthcare System; Dan Mareck, MD, Chief Medical Officer, Federal Office of Rural Health Policy/HRSA; George Zangaro, PhD, RN, Director, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, HHS Bureau of Health Workforce; Randy Longenecker, MD, Assistant Dean, Rural and Underserved Programs and Professor of Family Medicine, Ohio University; Judy Howe, PhD, Director, ORH Rural Health Training Initiative, Bronx VAMC; Peter Kaboli, MD, Director of the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center – Central Region, Associate Professor at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City VA Medical Center; Thomas Klobucar, PhD, Deputy Director, Office of Rural Health, VHA Office of Rural Health; and Janice Garland, MPH, Health Systems Specialist, Office of Rural Health, VHA Office of Rural Health (10P1R). We would also like to thank Roberta Shanman and Jody Larkin for the literature searches and Jeremy Miles for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 311 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

MacQueen, I.T., Maggard-Gibbons, M., Capra, G. et al. Recruiting Rural Healthcare Providers Today: a Systematic Review of Training Program Success and Determinants of Geographic Choices. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 191–199 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4210-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4210-z