Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore the feasibility and effectiveness of mindful walking in nature as a possible means to maintain mindfulness skills after a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) or mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) course. Mindful walking alongside the river Rhine took place for 1, 3, 6, or 10 days, with a control period of a similar number of days, 1 week before the mindful walking period. In 29 mindfulness participants, experience sampling method (ESM) was performed during the control and mindful walking period. Smartphones offered items on positive and negative affect and state mindfulness at random times during the day. Furthermore, self-report questionnaires were administered before and after the control and mindful walking period, assessing depression, anxiety, stress, brooding, and mindfulness skills. ESM data showed that walking resulted in a significant improvement of both mindfulness and positive affect, and that state mindfulness and positive affect prospectively enhanced each other in an upward spiral. The opposite pattern was observed with state mindfulness and negative affect, where increased state mindfulness predicted less negative affect. Exploratory questionnaire data indicated corresponding results, though non-significant due to the small sample size. This is the first time that ESM was used to assess interactions between state mindfulness and momentary affect during a mindfulness intervention of several consecutive days, showing an upward spiral effect. Mindful walking in nature may be an effective way to maintain mindfulness practice and further improve psychological functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The psychological effects of the 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) are getting increased attention in scientific research, with mindfulness techniques being recommended as valuable strategies to relate to negative thoughts and emotions. Mindfulness training aims to make participants more aware of their automatic reactions on a behavioral, emotional, and cognitive level, by encouraging them to engage in daily meditation practices. Non-judgmental observing of emotions or thoughts present here and now enables participant to react in a calm and “wise” manner in stressful situations (Kabat-Zinn 1994). Mindfulness has been shown to lead to improvements in depression, anxiety, stress, and quality of life in a variety of clinical populations as well as healthy participants (Gotink et al. 2015).

Although studies directly examining the necessity of ongoing practice are lacking, mindfulness participants are recommended to maintain mindfulness practice in order to maximize and sustain benefits. As many find it difficult to do this on their own, mindfulness centers often offer reunion meetings or silent days. Attendees have reported to experience these as a booster reminding them of their mindfulness practices and as a sanctuary where these practices are further nurtured (Hopkins and Kuyken 2012). So, it might be valuable to offer other easily accessible means to former participants of MBCT or MBSR courses to help maintaining their mindfulness practice.

One possibility that is available to many people is mindful walking. During the MBCT and MBSR training, participants are asked to pay attention to their senses (i.e., sight, hearing, smelling, tasting, bodily sensations), emotions, thoughts, and automatic behavioral patterns. They are encouraged to experiment with letting go of automatic behaviors (i.e., high demands, hurrying) and with approaching difficult emotions or situations (i.e., annoyance, sadness). During the training, participants get introduced to mindful walking, which has been described as “meditation in motion.” Mindful walking uses the everyday activity of walking as a mindfulness practice to become more aware of bodily sensations. The physical sensation of walking enables people to feel more “grounded” in the present moment (Segal, Williams, and Teasdale 2002). When people’s minds are occupied or stressed, paying attention to their physical movements can be an easy way to become more mindful.

Walking does not require expensive gear or tools, and it can usually be integrated into a person’s schedule without too many difficulties. Mindfulness and walking share similar experiences. Both require paying attention to bodily sensations and other sensory input like sights, sounds, or smells. In addition to the intrinsic link between mindfulness and walking, physical exercise in itself has a positive influence on psychological functioning and can reduce depressive symptoms (Nabkasorn et al. 2006; Salmon 2001; Scully, Kremer, Meade, Graham, and Dudgeon 1998). A recent meta-analysis in the UK shows that outdoor walking can lead to lower blood pressure, resting heart rate, body fat, body mass index, total cholesterol and depression, and increased VO2max and physical functioning (Hanson and Jones 2015). Other studies on environment and mental health have shown the benefits of walking in nature (Easley, Passineau, and Driver 1990; Hartig, Mang, and Evans 1991; Kaplan and Talbot 1983; Roe and Aspinall 2011). In summary, mindful walking in nature could contribute to keeping up both mindfulness practice as well as a healthy lifestyle, thereby reducing stress-related symptoms and diseases.

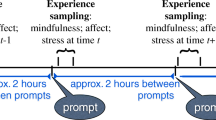

Little is known about how exactly mindful walking may affect mindfulness and psychological functioning. One method to measure relationships between mental states in a detailed way is experience sampling method (ESM). ESM enables repeated in-the-moment assessments of experiential states to measure detailed fluctuations in participants (Csikszentmihalyi and Larson 1987; Peeters, Nicolson, Berkhof, Delespaul, and deVries 2003), thereby minimizing retrospective bias and enhancing reliability and ecological validity (Csikszentmihalyi and Larson 1987). Earlier ESM studies found that mindfulness stimulates upward spirals of positive affect and positive cognition (Garland, Geschwind, Peeters, and Wichers 2015), and that induced mindfulness enhanced valence and calmness, where induced rumination reduced these states (Huffziger et al. 2013). Furthermore, Snippe, Nyklíček, Schroevers, and Bos (2015) investigated daily affect changes during an MBSR training, and reported that changes in mindfulness preceded changes in affect.

This pilot study aims to explore the feasibility and effectiveness of mindful walking as a way to maintain mindfulness skills in people who previously participated in either an MBCT or MBSR course. Using ESM data, we tested whether mindful walking has beneficial effects on momentary positive and negative affect, allowance of thoughts and emotions, and state mindfulness and compared to a control period. With time-lagged analyses, we also investigated temporal relations between state mindfulness (at time t−1) and momentary positive and negative affect (at time t), and vice versa. Finally, we tested whether walking more days leads to added benefits, compared to the first day of walking. On an exploratory base, we used questionnaires to see whether ESM results corresponded with changes in self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, brooding, and mindfulness skills. The current study is the first to investigate the relationship between state mindfulness and momentary affect with ESM during a multi-day mindful walking intervention.

Method

Participants

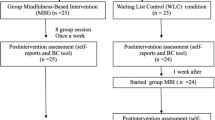

All adult participants who had previously completed either an MBSR or an MBCT course at the Radboudumc Centre for Mindfulness in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, were eligible to participate in the study. There were no restrictions in terms of age, current psychopathology, or duration since completion of the mindfulness course. Of the 49 people attending the organized information meeting, 32 chose to participate in the study. Three participants were excluded from analyses due to acquired brain damage associated with cognitive impairments, which raised uncertainty about whether they could properly complete the assessments. The remaining 29 participants were on average 54.3 years old (SD 9.0) and 69 % were female (see Table 1). Six persons had participated in an MBSR course (general population) and 23 in an MBCT course (mainly patients with recurrent depressive disorder). Participation in these courses took place 2.7 years (SD 1.5) before the study. Many of the participants regularly attended reunion meetings at the Radboudumc Centre for Mindfulness. Ten people (34.5 %) participated in the 1-day walking retreat, 14 (48.3 %) in the 3-day walking retreat, and five (17.2 %) walked for six or more days.

Procedure

By means of the center’s website, a Facebook group, and on reunion days at the center, adult participants of previous training groups were invited to an informal meeting at which they were informed about both the mindful walking period itself and the associated self-report measures and experience sampling. After the meeting, people gave their definitive consent to participate. For participants of the 1 and 3-day walking periods, all costs were reimbursed. Participants of the six or more days walking periods received €50 per day as a compensation for their accommodation costs. Participants were provided with smartphones to complete the experience sampling for ten quasi-random times a day both during the mindful walking period and control period (five times a day for those walking six or more days). In addition, participants were asked to complete self-report questionnaires before and after both the mindful walking period, and the control period of similar duration exactly 1 week before. As participants were no (longer) patients of the Radboud University Medical Center and the intervention and assessments were not considered to represent any risk to the participants, the medical ethics committee of the hospital waived the need to apply for formal ethical permission (CMO registration no. 2014/250).

The walking route took place alongside the river Rhine, from where it enters the Netherlands to where it joins the North Sea, reaching a total length of 240 km. The route was mostly unpaved, and participants were instructed to keep the river on their right and to overcome obstacles they might come across, such as fences and detours, in their own way. They received a map with a rough description of the route and available accommodation addresses.

People were offered three different possibilities to participate in the mindful walking: either as a 1-day walking retreat in a group, accompanied by a mindfulness teacher; or a 3-day walking retreat in a group, accompanied by two mindfulness teachers; or a solitary walking retreat of 6 days or more, with the possibility of daily contact with a mindfulness teacher by telephone, text, or email. Participants were instructed to walk the route silently except for times conversation was necessary for practical purposes (i.e., arrival at accommodation). They were reminded to pay attention to their senses (i.e., sight, hearing, smelling, tasting, bodily sensations), emotions, thoughts, and automatic behavioral patterns. They were encouraged to experiment with letting go of automatic behaviors (i.e., high demands, hurrying) and with approaching difficult emotions or situations (i.e., annoyance, sadness). They were also encouraged to choose wisely between walking alongside the river, the grass bank or the surfaced road on the dyke. For the 1-day walking retreat, there was a 15-min sitting meditation at the start of the day, at lunchtime, and at the end of the day. For the 3-day walking retreat, participants were offered standing yoga exercises for 30 min before breakfast, a sitting meditation of 30 min followed by a plenary enquiry in the evening and the possibility of individual interviews with one of the mindfulness teachers. The participants walking for six or more days walked on their own and hence only received the general walking meditation instructions. They were, however, encouraged to spend at least half an hour every day to write about their experiences and process in a personal diary. They also had the possibility of individual interviews at the end of the day to discuss their process with a mindfulness teacher.

The control period was of similar duration as the mindful walking period the participant had opted for and took place exactly 1 week before the intervention period, i.e., when the mindful walking period was from Friday to Sunday, the control period was from Friday to Sunday as well. The participants received no particular instructions about what to do during the control period.

Measures

The assessments consisted of both electronic brief questions using the ESM at quasi-random times during the control and intervention periods, and self-report questionnaires before and after the control and mindful walking periods.

To closely monitor the course of participants’ experiential state, we collected ESM data using smartphones that quasi-randomly gave a signal several times a day between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. to cover the period of mindful walking, with a maximum time in between of 90 min. For the 1- and 3-day walking periods, samples were taken ten times a day, and for the six and more day retreats, five times a day. After each signal, participants answered 18 Likert scale items each ranging from 0 (not at all) to 7 (very much). All items are listed in Table 2. The first nine items comprised different moods (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen 1988) with five items measuring positive affect (content, cheerful, relaxed, energetic, and calm) and four negative affect (sad, irritated, insecure, tense). The selection of affect items was based on previous experience sampling studies in this area of research (Geschwind, Peeters, Drukker, van Os, and Wichers 2011; Wichers et al. 2010). Cronbach’s alpha of the positive affect items was 0.92 and of negative affect items 0.89. The items on affect were followed by four items measuring suppressing or allowing negative thoughts and emotions. These items were combined into one outcome “allowing,” indicating the ability to allow negative thoughts and emotions, and not suppress them. Cronbach’s alpha of these four items was 0.79. Finally, participants answered the items with the highest factor loadings on four of the five subscales of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (Baer et al. 2008), namely Observing, Acting with awareness, Non-judgment, and Non-reacting. An item on self-compassion was added instead of an item for Describing, which has not been found influential in previous research (Schroevers and Brandsma 2010). The Cronbach’s alpha of these five items was 0.80.

All items not filled in within 15 min after the signal were excluded from analysis, as reports completed after this interval are considered less reliable and less ecologically valid (Delespaul 1995). Experience sampling data (control or intervention period) with fewer than 33 % valid reports were also excluded from the analysis.

The Dutch version of the Depression Anxiety Stress (DASS-21) questionnaire was used to measure depression, anxiety, and stress. The three subscales each consist of seven items scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (very often). The DASS-21 has good validity and reliability in a non-clinical sample (Henry and Crawford 2005); Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.90. The brooding subscale of the 22-item Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) (Schoofs, Hermans, and Raes 2010) was used to assess rumination. This scale consists of five items scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (very often). Cronbach’s alpha of this subscale was 0.84.

As the pre and post assessments were so close together, particularly during the 1-day walking retreat, we selected a measure assessing mindfulness as a state rather than a trait, i.e., the subscales Decentering and Curiosity of the Toronto Mindfulness Scale (Lau et al. 2006). These two subscales are significantly and positively correlated with absorption and awareness of one’s surroundings. Curiosity is also significantly correlated with awareness of internal states (thoughts and feelings). The 13 items are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much so). Their Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81.

Data analyses

All analyses were performed in SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp 2013). The approach used for the ESM data was the following: ESM data have a hierarchical structure. Thus, multiple observations (level 1) are clustered within participants (level 2). Mixed effect multilevel analyses with random (i.e., participant-specific) intercepts were used in order to take the variability associated with each level of nesting into account (Snijders 2012). On top of the random intercept, all time-lagged analyses used autocorrelated covariance structures with a random slope.

In the questionnaire data, 6.9 % of values were missing, and these were imputed based on multiple imputation regression with ten iterations. ANCOVA analyses describe the levels of dependent variables depression, anxiety, stress, brooding, mindfulness decentering, and mindfulness curiosity at each time point adjusted for gender, clinical indication, and number of days walked. This way the effect of the intervention could be observed more accurately, as gender, clinical indication and number of days walked may influence the outcome. In order to compare the different outcome measures, Cohen’s d for within-subject measurements (Morris and DeShon 2002) was calculated by comparing the mean delta of the pre-measurement with the mean delta of the post-measurements (based on the ANCOVA results). In other words, Cohen’s d indicates whether the change during the walking period was larger than during the control period (see Table 4).

Results

In addition to the three cognitively impaired participants, data from two more participants were excluded from the ESM analysis because the proportion of valid assessments was less than 33 %. The baseline assessment of one participant was excluded from the analyses due to procedural problems during data collection; the data of the intervention period were still used.

The results of the regression analyses are presented in Table 3. Compared to the control period, the mindful walking periods resulted in a significant increase of positive affect (β = 0.91, p < 0.001) and state mindfulness (β = 0.98, p < 0.001), and a reduction of negative affect (β = −0.71, p < 0.001). Allowing thoughts and emotions showed only a trend of effect (β = 0.43, p = 0.067). Positive affect and mindfulness were highly correlated (r = 0.75, p < 0.001), and there was a negative correlation between negative affect and mindfulness (r = −0.66, p < 0.001). State mindfulness in the previous moment appeared to predict positive affect in the next, even after controlling for affect at the previous moment (β = 0.18, p < 0.001). Similarly, positive affect at the previous moment appeared to predict mindfulness in the next, even after controlling for mindfulness at the previous moment (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). Negative affect showed an opposite relationship: after controlling for the previous level, state mindfulness predicted a reduction of negative affect in the next moment (β = −0.14, p < 0.001) and negative affect predicted a reduction of mindfulness in the next moment (β = −0.19, p < 0.001).

Split file | Parameter | β | SE | p value | Lower | Upper |

95 % CI | 95 % CI | |||||

Intervention group | Intercept | 1.99 | 0.26 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 2.50 |

Negative affect previous moment | 0.41 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.49 | |

Mindfulness previous moment | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.25 | −0.10 | |

Control group | Intercept | 1.88 | 0.25 | <0.001 | 1.39 | 2.38 |

Negative affect previous moment | 0.48 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.56 | |

Mindfulness previous moment | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.001 | −0.22 | −0.06 |

Mindfulness on the previous day did not predict positive affect on the next day, even after controlling for positive affect on the previous day (β = 0.23, p = 0.192), nor did mindfulness on the previous day predict a reduction of negative affect on the next day (β = −0.11, p = 0.411). In contrast with the momentary analyses, positive affect on the previous day did significantly predict a reduction of mindfulness on the next day when controlling for the level of mindfulness on the day before (β = −0.36, p = 0.027), and negative affect on the previous day predicted an increase of mindfulness the next day (β = 0.41, p = 0.002). Both state mindfulness and positive affect appeared to significantly improve with the number of days walked (β = 0.14, p < 0.001, and β = 0.12, p = 0.011, respectively), but negative affect did not (β = −0.04, p = 0.286).

Because the questionnaire data are underpowered, we present Cohen’s d to give an indication of the effect size, rather than focusing on statistical significance. During the control period (between measurements 1 and 2), there were no consistent or large changes from pre to post (Table 4). During the intervention period (between measurements 3 and 4), depression, anxiety, stress, brooding, and mindfulness all improved moderately (Cohen’s d ranged from 0.27 for depression to 0.53 for brooding), but compared to the control period these changes were not statistically significant.

Discussion

This pilot study explored the feasibility and effectiveness of mindful walking as a way of maintaining practice after having participating in an MBCT or MBSR course, using standard questionnaires as well as experience sampling. The ESM data shows that mindful walking resulted in significant improvements of both mood and mindfulness skills. Moreover, the ESM data provided more detailed insight in how the moment-to-moment changes in mood and mindfulness affect each other during the mindful walking period: an earlier randomized controlled trial showed that MBCT increases positive affect as well as individual’s susceptibility to rewarding situations in daily life (Geschwind, Peeters, Huibers, van Os, and Wichers 2012). The current data corroborate and extend this finding by showing that state mindfulness and positive affect, measured during a mindfulness intervention which covered a period of consecutive days, appear to stimulate each other. Increased state mindfulness predicted a more positive affect in the next moment and less negative affect, which in turn predicted a higher state mindfulness, thereby creating an upward spiral from one moment to the next. The moment-to-moment ESM data have enough power to monitor this relationship. The less well-powered day-to-day data show a different trend, in the sense that mindfulness did not predict either positive or negative affect, and positive affect seemed to predict less mindfulness and negative affect more. It could be that over such a period, having a good day slackens mindfulness practice on the next, where having more negative feelings increases practice the next day, but these findings need more replication in a larger sample before any conclusions can be drawn.

Our findings are in accordance with previous research showing that changes in mindfulness precede changes in affect (Snippe et al. 2015). Garland and colleagues compared interactions between positive affect and cognitions before and after MBCT and found that MBCT appeared to enhance upward spirals between positive affect and cognition (Garland et al. 2015). While Garland and Snippe investigated the influence of mindfulness training on mood, we investigated the moment-to-moment temporal relationships between mindfulness and mood. Our method of analysis adheres to state of the art principles in multilevel time-series modeling, which has also been used in previous high-impact publications (Collip et al. 2013; Geschwind et al. 2011; Snippe et al. 2015). Regarding the (underpowered) self-report questionnaires, the results were in line with the ESM outcomes: mindful walking can reduce depression, anxiety, stress, and brooding and increase mindfulness skills, although these changes did not reach statistical significance compared to a control period of similar length.

Although the current study offers promising results, there are several limitations that have to be taken into account. First, this is a small sample of self-referred participants. Chances are that there is a selection bias of people who benefitted from the mindfulness training or believe in the effect of walking in nature, and thus were more motivated to participate in this study. As the study population was limited to people who previously participated in MBCT of MBSR, it is not sure what the effectiveness of the mindful walking would have been in people who do not have that experience. Our choice of restricting the study population to graduates of the mindfulness courses was influenced by the fact that we anticipated that being in silence for prolonged periods of time would not be easy for people who are naive to meditation. We also anticipated that it would not have been easy for them to pay non-judgmental attention to bodily sensations, emotions, and thoughts, to become aware of automatic patterns and start experimenting with alternative ways of dealing with situations without any further guidance. However, as the mean time since completion of the MBCT or MBSR course was several years for most participants, it remains unsure whether the effectiveness of the mindful walking was due to consolidating prior practice or to being offered something new. Many of the participants, though, had been maintaining their mindfulness skills by attending the reunion meetings of the Radboudumc Centre for Mindfulness.

With regard to the small sample size, the questionnaire results have been more affected than the ESM data due to the number of repeated measurements per person. In addition, although pragmatic, using subscales of validated questionnaires may reduce validity and reliability of our questionnaire measurements (Breakwell, Smith, and Wright 2012). Also, while most participants previously participated in an MBCT group for their recurrent depression, no formal psychiatric assessment has been done before inclusion of participants, so apart from demographic information unfortunately no further information about current psychopathology is available.

Although the study included a control period, it did not include a control group. Consequently, it remains unclear if similar effects would be evident with any other activity in a group or in nature. Furthermore, the intervention varied in length and in presence of a group leader. As the intervention consisted of a combination of mindfulness practice and physical exercise, it also remains unclear to what extent either of these is helpful. Possibly, monitoring of physical exercise in addition to mood and mindfulness skills in a next study might enable us to further disentangle this process. Finally, the study did not include a follow-up period, preventing conclusions about the consolidation of the treatment effects.

The results of this study should be regarded as preliminary. Replication in a properly powered randomized controlled trial, including a control group and a follow-up period, is necessary. The ESM data, however, give us a glimpse of a possible working mechanism between mindfulness and enhanced well-being, through upward spiral effects between state mindfulness and improved mood from one moment to the next.

References

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and non-meditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342.

Breakwell, G., Smith, J. A., & Wright, D. B. (2012). Research methods in psychology. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Collip, D., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., Myin-Germeys, I., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2013). Putting a hold on the downward spiral of paranoia in the social world: a randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in individuals with a history of depression. Plos One, 8(6).

Corp, I. B. M. (2013). IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1987). Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175(9), 526–536.

Delespaul, P. A. E. G. (1995). Assessing schizophrenia in daily life: The experience sampling method. Maastricht: IPSER.

Easley, A. T., Passineau, J. F., & Driver, B. L. (1990). The use of wilderness for personal growth, therapy and education. Colorado Fort Collins, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station

Garland, E. L., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., & Wichers, M. (2015). Mindfulness training promotes upward spirals of positive affect and cognition: multilevel and autoregressive latent trajectory modeling analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 15.

Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., Drukker, M., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2011). Mindfulness training increases momentary positive emotions and reward experience in adults vulnerable to depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(5).

Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., Huibers, M., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2012). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in relation to prior history of depression: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 201(4), 320–325.

Gotink, R. A., Chu, P., Busschbach, J. J., Benson, H., Fricchione, G. L., & Hunink, M. G. (2015). Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. Plos One, 10(4).

Hanson, S., & Jones, A. (2015). Is there evidence that walking groups have health benefits? British Journal of Sports and Medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Hartig, T., Mang, M., & Evans, G. W. (1991). Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environment and Behavior, 23(1), 3–26.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239.

Hopkins, V., & Kuyken, W. (2012). Benefits and barriers to attending MBCT reunion meetings: an insider perspective. Mindfulness, 3(2), 139–150.

Huffziger, S., Ebner-Priemer, U., Eisenbach, C., Koudela, S., Reinhard, I., Zamoscik, V., & Kuehner, C. (2013). Induced ruminative and mindful attention in everyday life: an experimental ambulatory assessment study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44(3), 322–328.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are. New York: Hyperion.

Kaplan, S., & Talbot, J. F. (1983). Behavior and the natural environment (pp. 163–203): from Psychological benefits of a wilderness experience, Springer.

Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., & Devins, G. (2006). The toronto mindfulness scale: development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445–1467.

Morris, S. B., & DeShon, R. P. (2002). Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 105–125.

Nabkasorn, C., Miyai, N., Sootmongkol, A., Junprasert, S., Yamamoto, H., Arita, M., & Miyashita, K. (2006). Effects of physical exercise on depression, neuroendocrine stress hormones and physiological fitness in adolescent females with depressive symptoms. European Journal of Public Health, 16(2), 179–184.

Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., Delespaul, P., & deVries, M. (2003). Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(2), 203.

Roe, J., & Aspinall, P. (2011). The restorative benefits of walking in urban and rural settings in adults with good and poor mental health. Health & Place, 17(1), 103–113.

Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), 33–61.

Schoofs, H., Hermans, D., & Raes, F. (2010). Brooding and reflection as subtypes of rumination: evidence from confirmatory factor analysis in nonclinical samples using the Dutch Ruminative Response Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(4), 609–617.

Schroevers, M. J., & Brandsma, R. (2010). Is learning mindfulness associated with improved affect after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy? British Journal of Psychology, 101(1), 95–107.

Scully, D., Kremer, J., Meade, M. M., Graham, R., & Dudgeon, K. (1998). Physical exercise and psychological well being: a critical review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(2), 111–120.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to relapse prevention. New York: Guilford.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (2012). Multilevel Analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage Publishers.

Snippe, E., Nyklíček, I., Schroevers, M. J., & Bos, E. H. (2015). The temporal order of change in daily mindfulness and affect during mindfulness-based stress reduction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 106.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Wichers, M., Peeters, F., Geschwind, N., Jacobs, N., Simons, C. J. P., Derom, C., & van Os, J. (2010). Unveiling patterns of affective responses in daily life may improve outcome prediction in depression: a momentary assessment study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 124(2), 191–195.

Acknowledgments

Funding: the development of the walking route which this study used was supported by a green deal between the Dutch Ministry of Economic affairs, the Province of Gelderland, and Menzis health insurance. There were no competing interests among the authors and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gotink, R.A., Hermans, K.S., Geschwind, N. et al. Mindfulness and mood stimulate each other in an upward spiral: a mindful walking intervention using experience sampling. Mindfulness 7, 1114–1122 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0550-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0550-8