Abstract

Purpose of Review

Liver disease is an important clinical and global problem and is the 16th leading cause of death worldwide and responsible for 1 million deaths worldwide each year. Infectious disease is a major cause of liver disease specifically and overall is even a greater cause of patient morbidity and mortality. Tools to study human liver disease and infectious disease have been lacking which has significantly hampered the study of liver disease generally and hepatotropic pathogens more specifically. Historically, hepatoma cell lines have been used for in vitro cell culture models to study infectious disease. Significant differences between human hepatoma cell lines and the human hepatocyte has hampered our understanding of hepatocyte pathogen infection and hepatocyte-–pathogen interactions.

Recent Findings

Despite these limitations, great progress was made in the understanding of specific aspects of the life cycle of the canonical hepatocyte viral pathogen, Hepatitis C Virus. Over time various specific drugs targeting various proteins of the HCV virion or aspects of the HCV viral life cycle have been created that enable almost complete elimination of the virus in vitro and clinically. These drugs, direct-acting antivirals have enabled achieving sustained virologic response in over 90–95 percent of patients.

Summary

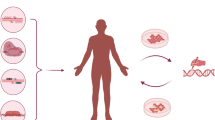

Despite the development of direct-acting antivirals and the extreme success in achieving sustained virologic response, there has only been limited success elucidating host–pathogen interactions largely due to the poor nature of the hepatoma platform. Alternative approaches are needed. Pluripotent stem cells are renewable, can be derived from a single donor and can be efficiently and reproducibly differentiated towards many cell types including ectodermal-, endodermal-, and mesodermal-derived lineages. The development of pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells (iHLCS) changes the paradigm as robust cells with the phenotype and function of hepatocytes can be readily created on demand with a variety of genetic background or alterations. iHLCs are readily used as models to study human drug metabolism, human liver disease, and human hepatotropic infectious disease. In this review, we discuss the biology of the HCV virus, the use of iHLCs as models to study human liver disease, and review the current work on using iHLCs to study HCV infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infectious diseases are a major public health concern as the second leading cause of death and responsible for one-fifth of deaths worldwide [1]. Currently, the strategy to treat infectious diseases is based on therapies targeting the infectious agent but this approach over time through evolutionary pressure and selection has led to the emergence of multidrug resistance and thus reduced pathogen susceptibility. Therefore, an improved understanding of host–pathogen interactions and response leading to the identification of the host factors involved in host–pathogen susceptibility and resistance is crucial to understanding and impacting disease pathogenesis. Improved knowledge of these host factors will enable the development of clinical therapies based on enhancing host immune response or altering host susceptibility and resistance (rather than through targeting the pathogen which leads to pathogen resistance over time). More specifically, the host immune response to viral infections is characterized by various independent components; physical barriers, innate immunity, and cellular immunity [2, 3]. The innate immunity in particular has both soluble and cellular components all of which have been demonstrated to be upregulated early after initial viral infection. Innate immunity is driven by host genetic factors and their impact on viral infection has been shown to be key regulators of viral infection. Many of these approaches have focused on using 3T3 cells, HUH7 cells, and other prototypic cell lines which are easy to maintain and work with but are limited in their ability to recapitulate normal human cellular function and phenotype [2, 4, 5]. Consequently, the study of many pathogens and host–pathogen interactions has been more limited or constrained as the pathogen life cycle cannot reliably and robustly be reproduced in vitro in primary cells [3].

Nowhere is this clearer than in hepatotropic infections such as in Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) or Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [5]. HBV as a prototypical hepatotropic viral pathogen is the most common viral hepatitis having infected over two billion people and chronically infecting more than 400 million worldwide, putting them at increased risk to develop cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [6, 7]. In the United States, over one million people have chronic hepatitis B viral infection [7]. Clinical therapy is targeted to the suppression of viral replication but the virus is able to persist in a nonreplicative covalently closed circular form called cccDNA, with the potential to reactivate upon immune suppression or with aging [6, 8]. As a consequence, the hepatitis B virus in chronic HBV infections is challenging to eradicate and cure is rare [6, 8]. The difficulty in the development of new HBV therapies results from the lack of good model systems due to the virus’s narrow host range and cellular tropism for hepatocytes. As an example, despite the identification of HBV in 1968, the entry receptor (NTCP) for hepatitis B virus was only first identified in 2012 [9].

Therefore, the use of more representative and functional cell types is required to better recapitulate the viral life cycle and host–virus interactions. The idea of cellular reprogramming in that one can convert the phenotype of a cell through genetic or cellular manipulation is an old one and originates as early as the 1950s with classic experiments using frog oocytes to reprogram adult nuclei to form whole embryos (leading to the development of somatic cell nuclear transfer) [10]. This ability of single or multiple transcription factors to modify epigenetic cell regulation and gene expression and reprogram once cell type to another was definitively demonstrated when a single transcription factor MyoD could reprogram fibroblasts into myoblasts [11•]. This idea culminated with the discovery and generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) which are generated through the exogenous expression of various factors (initially with four factors OCT4, Sox2, KLF4, and MYC) in adult cells to form cells morphologically, phenotypically, and functionally similar cells to embryonic stem cells that are capable of establishing cell types of all lineages [12, 13]. iPSCs and human embryonic stem cells are pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and are renewable, can be derived from a single donor, and can be genetically modified [12, 13]. PSC cells can be efficiently and reproducibly differentiated towards many cell types including ectodermal-, endodermal-, and mesodermal-derived lineages in a step-wise and predictable manner [14•], [15], [16]. PSC-derived cell types have differentiated and phenotypic function similar to that of primary human cell correlates and thus can serve as ideal replacements for currently used cell lines [15].

Using iPS- and iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells as Models to Study Human Liver Disease

iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells as Models to Study Human Drug Metabolism and Cell Response

Although the focus of this review is on the applications of PSC-derived cells types to study infectious disease, iPSCs contain the genetic contributions of the donor and therefore provide an excellent opportunity to model human disease broadly and human liver disease specifically. iPSCs- and iPS-derived hepatocyte-like cells (iHLCs) offer multiple opportunities including hepatocyte-like cell generation for possible cell replacement therapy, disease modeling, drug modeling, as well as a variety of applications. While cell replacement therapy would address a significant clinical need [15], this therapeutic goal is still far on the horizon, and thus the near-term potential of iHLCs may rest in applying them to serve as a platform for disease modeling and drug testing [17]. Genetic variation impacts cellular response and metabolism of various drugs. PSC-derived hepatocytes therefore can be used to model drug metabolism and production of daughter products and may help identify the production of clinically significant drug metabolites that may impede clinical trials and drug failures. Moreover, such approaches may help identify the impact that rare cytochrome P450 genotypes have on drug metabolism and help lead to drug (and thus patient) profiling of drugs before they reach the broader market. This approach could greatly impact the cost of drug development which currently is influenced by the attrition rate of tested compounds; for every drug that reaches the marketplace, 7500–10,000 molecules are tested in a preclinical setting [18]. More broadly, it is recognized that genetic variation greatly impacts the individual responses to drug treatment. PSC-derived hepatocytes would allow for the identification of the patient population subsets most likely to respond to various drug therapies in advance of actual drug treatment. Efforts to stratify patients based on genetic profiling are already being used in cancer therapy and are likely to extend to a variety of new and novel treatments in a revolution commonly called precision medicine [19].

iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells as Models to Study Human Liver Genetic Inborn Errors of Metabolism

As mentioned iPSC can be generated from a variety of donors and have been generated from patients with hepatocyte-based genetic inborn errors of metabolism or diseases. These diseases include A1AT deficiency [20–22], familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) [20, 23], glycogen storage disease (GSD) [20, 24, 25], Gaucher’s disease [26] Crigler-Najjar Type 1 [20, 24, 27], hereditary tyrosinemia [20, 24], progressive familial hereditary cholestasis [24], Wilson’s disease [28], Citrin deficiency [29] and defective mitochondrial respiratory chain complex disorder [30]. Illustrating this approach, Cayo et al. generated iPSCs from the famous patient JD with familial hyperlipidemia (of Brown and Goldstein fame) and demonstrated that iHLCs generated from these cell lines had a similar lipid profile, phenotype and defects to those described in the patient [23]. In all of these papers, it was demonstrated that the iHLCs recapitulate the disease phenotypes and represent an invaluable opportunity to study liver disease phenotypes in vitro thereby enabling disease study and drug development. One challenge present in all of these studies is that each patient derived iPSC cell line has a variety of genetic variants and/or mutations (outside of the evaluated and studied mutation) that may modify or impact disease phenotype. Reproducible differences in disease phenotypes may therefore be due to these genetic modifiers rather than primarily due to the disease mutation. Therefore, identifying appropriate controls is critical to evaluate observed phenotypes and traditionally gene repair has been used to produce these internal controls. Future studies may therefore be able to capitalize on the robustness of these platforms to identify the genetic and epigenetic modifiers that modulate disease phenotype.

Genome Engineering Approaches in Human iPS- and Human iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells

One significant advance outside of the stem cell community (which dovetails well in addressing the aforementioned concerns) and is rapidly impacting the scientific community is genome engineering; starting initially with zinc-finger nucleases [31], transcription activator-like effector nuclease [32] and now with the discovery and application of Cas9 endonuclease [33]. The RNA-guided CrispR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats)-associated nuclease Cas9 offers targeted DNA binding (enabling DNA nicking/cleavage or transcriptional activation) at specific sites in the genome of mammalian cells [33, 34]. Native Cas9 is an endonuclease which can be targeted using a synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to specific genomic targets and induce DNA double-strand breaks resulting in insertion/deletion (indel) mutations resulting in a frame-shift and subsequent allele loss [34]. The specificity of Cas9 is conferred by short guide sequences enabling the development of large libraries of guide sequences targeting the whole genome enabling genome-scale targeting and subsequent knockdown or targeted genome manipulation [34]. These approaches enable both genetic correction (in the case of cell lines generated from patients with specific mutations) or to generate cell lines with targeted mutations enabling cell lines with various mutations to be generated in a syngeneic background. This “genome engineering” technique was used to successfully correct point mutations in A1AT disease iPSCs [35]. Alternatively, the PCSK9 gene was targeted and mutated using CrispR-Cas9 in the mouse liver generating mice with an altered lipid profile mimicking the human disease phenotype or in humanized human liver chimeric mice [36, 37]. When taken together with the aforementioned work in iPSC generation, concern over adequate controls can be eliminated using genome engineering approaches in syngeneic genetic backgrounds with only the generated mutations then responsible for the observed phenotypes.

Summary

Pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells represent a unique opportunity for both clinical and basic science translation and has the potential for translation as a cell replacement therapy, in disease modeling, drug modeling, as well as a variety of applications to model human liver disease.

iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells as Models to Study Infectious Disease

The generation of iPSC and genome engineering technologies has revolutionized the ability to study and model the mechanisms of genetic diseases and are uniquely situated to study host–pathogen interactions, infectious disease pathogenesis, and genetic susceptibility or resistance to infection. iPSC-derived cell types represent a paradigm shift in enabling the wide availability of close cell correlates for the investigation of viral tropism, pathogenesis, latency, reactivation, and host response all within human and relevant cell types (which represents a significant advance over traditional prototypic cell lines). Several studies have used human iPSC to model infectious disease with a variety of pathogens in iPSC-derived cell types including herpes simplex virus (HSV) (neural progenitor cells) [38•], varicella zoster virus (VZV) (neural progenitor cells) [39], human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (neural progenitor cells, neurons) [40], hepatitis B (HBV) (iHLCs) [41], hepatitis C (HCV) (iHLCs) [42•], [43], [44••], hepatitis E virus (HEV) (iHLCs) [45], influenza (pulmonary epithelial cells) [46], coxsackievirus (cardiomyocytes) [47], and plasmodium falcipirum (iHLCs) [48].

Human Liver Disease Epidemiology

Liver disease is an important clinical problem, impacting over 30 million Americans and 600 million people worldwide and is the 12th leading cause of death in the United States, 7th in Europe, and 16th worldwide (Liver disease is responsible for over 30,000 deaths in the United States and 1 million deaths worldwide each year [49]). Due to an aging population, liver morbidity has increased despite improved treatment tools. Long-term infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a significant cause of current worldwide liver morbidity and mortality, infecting 160–190 million people worldwide (approximately 3 % of the worldwide population) and puts these people at risk to develop liver injury including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [50, 51]. Although HCV incidence has decreased significantly over the last 20 years, due to the long and often silent incubation period it is estimated that the number of undiagnosed individuals will continue to increase over the next decade. Unfortunately, an effective prophylactic HCV vaccine is not available. In contrast, several effective direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAAs) targeting HCV viral factors efficiently block HCV replication and result in a sustained virological response (viral cure) in over 90 percent of patients [52, 53]. However, due to the high cost of DAA treatment and the lack of a HCV vaccine, HCV eradication is going to be challenging and elusive particularly in the developing world [54, 55].

Hepatitis C Virus Biology and Platform Development

HCV Description

HCV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae viral family (other family members include yellow fever, dengue fever, and Zika virus) that infects patients via direct blood contact (i.e., contaminated blood or blood supplies or intravenous drug use) [50, 51]. It primarily targets primary hepatocytes [51]. HCV strains are classified into seven genotypes based on sequence analysis with genotypes 1 and 3 the most prevalent worldwide [56]. Of patients infected with the virus, approximately three-quarters go on to develop a chronic infection [52]. The HCV virus has a very specific species tropism (i.e., human and chimpanzee) and cell tropism (i.e., hepatocyte) that initially hampered HCV research [57]. HCV was first discovered in 1989 [58] but the lack of a cell culture system (as well as a virus capable of launching HCV infection) significantly hampered the study of HCV [59]. Recognition that the 5’ or 3’ end of the HCV genome may be incorrect or incomplete led to the discovery that the HCV consensus genomes lacked part of the 3’ NTR [60–63]. Consensus sequences were used to correct errors or deleterious mutations present in the HCV genome. Combining both of these approaches led to the development of HCV clones that were infectious in vivo in chimpanzees but for reasons that remained unclear at the time did not lead to the production of infectious viral particles in vitro [64, 65]. Many attempts to detect viral replication led to the realization that it also would be impossible to detect the low level of HCV replication (if present) in the background of the large amount of input HCV RNA used to initiate infection. Therefore, different systems were developed that would enable the detection of viral replication.

Development of the Subgenomic Replicon and HCV Permissive Cell Lines

Inspired by work in other positive strand RNA viruses that showed that the structural proteins are dispensable for RNA replication [66], the minimal set of HCV proteins required to initiate and maintain HCV replication was determined and subgenomic replicons containing luciferase reporters or antibiotic selection markers were created, establishing for the first time a cell-based model for HCV replication [67–69]. Over time, adaptive mutations were selected during viral replication leading to the emergence of HCV variants with higher replicative capability [70–72]. Moreover, isolation and treatment (with interferon or drugs targeting HCV replication) of selected replicon cells led to “cured cells” along with the development of cells that were more highly permissive than the parental cells (i.e., leading to the development of permissive clones such as Huh-7.5 cells) [73]. Subgenomic replicons have been reported for most HCV genotypes and significantly contributed to the development of direct-acting antivirals. After the creation of efficiently replicative subgenomic clones, it was hoped that a permissive cell culture system would be easily created. With that in mind, genomic replicons encoding the complete HCV polyprotein were constructed [74]. These genomic replicons were capable of replicating in Huh7 parent and daughter cell lines but could not support virus particle production [74, 75]. Perturbation of genomic replicon system or selection markers did not lead to improved results, and therefore, it was believed that either the Huh7 cell line could not support robust virus production or that mutations in the HCV genome were not supporting adequate viral replication and virion production simultaneously [76].

Discovery of the JFH-1 Isolate and Cell Culture Production of HCV

The discovery of the JFH-1 isolate [77] coupled with the development of the huh-7.5 cell line (clone of huh7 which has a defect in Rig-I which mutes the antiviral response to infection) led to the production of high titers of infectious HCV virions (cell culture derived HCV or HCVcc) [78]. Despite these significant advances, HCV replication and viral infection have largely been studied in Huh-7 cell lines or its daughter lines. While these hepatoma cell lines now support high levels of HCV viral replication and/or virion production, the interpretation of the impacts HCV has on hepatocyte biology and that the hepatocyte has on the HCV virus is limited given the constraints of hepatoma cell lines. These limitations include the significant differences in RNA and protein expression and production between hepatoma cell lines and primary human hepatocytes. Moreover, these cell lines are rapidly proliferative and are not polarized in vitro which stands in stark contrast to primary human hepatocytes phenotype and function. Moreover, these hepatoma cell lines (i.e., Huh7.5) are known to have significant defects in the antiviral response [3, 79, 80]. Therefore, these limitations can be overcome by using primary human hepatocytes and several reports have shown that primary human hepatocytes can support HCV infection in vitro [81, 82]. Unfortunately, there are several limitations using primary human hepatocytes including the difficulty and variability in hepatocyte sourcing as well as the difficulty in maintaining the differentiated hepatocyte state in vitro [83]. Moreover, in several studies, only low-level replication and virion production were demonstrated. Several platforms that enable the enhanced survival and differentiated function of primary human hepatocytes have been developed [84–86]. Further improvements in primary human hepatocyte were realized when micropatterned co-cultures of primary human hepatocytes organized on collagen-coated islands along with fibroblasts maintain hepatocyte function [85], HCV permissiveness, and enabled HCV infection, viral replication, along with the upregulation of the antiviral response [87].

iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells in the Study of Hepatitis C Virus Infection

Given the challenges with working with primary human hepatocytes (particularly challenges with cell sourcing and controlling for the genetic backgrounds of the donor), using human PSC derived hepatocyte-like cells as a cell source becomes very appealing. Moreover, interest in understanding the role that various host genetic variants play in HCV infection becomes tractable questions in a PSC-based platform. In one early study, Yoshida et al. demonstrated entry and viral replication with HCV pseudoparticles (HCVpp) and HCV subgenomic replicons, respectively [88••]. Several studies reported that hES-derived hepatocyte-like cells [44••], [89] or iPSC-derived hepatocyte-like cells (iHLCs) [42•], [43], [44••], [89]were permissive to infection with HCVcc and allowed for the production of productive and infectious virions thereby demonstrating completion of the HCV viral life cycle. HCV has a narrow species tropism which was leveraged to investigate the species–species barriers to viral entry by Sourisseau et al. whereby they demonstrated that pigtail macaque (Macaca nemestrina) iHLCs were less supportive of HCV infection and that this limitation was largely driven by the differences in human CD81 versus pigtail macaque CD81 (as CD81 is one of the canonical viral entry factors) [91•]. Overexpression of human CD81 in pigtail iHLCs or inoculating iHLCs with a virus which was less dependent on CD81 for viral entry helped improve viral entry [91•]. iHLCs express high levels of the entry factors required for HCV entry including CD81, SR-B1, claudin1, and occludin [42•]. Moreover, expression of these markers was largely restricted to differentiated iHLCs (with the exception of occludin and to a lesser extent for SR-B1 which is expressed by PSC and early differentiated cells) [44••]. Moreover, the microRNA, miR-122 which is required for HCV viral RNA stabilization and viral protein propagation is expressed at high levels in iHLCs [42, 92•], [92]. Analysis of iPSC and iHLC transcriptional gene expression confirmed that previously identified host factors [2] shown to be important in HCV viral replication were enriched in iHLCs [42•]. In several reports, HCV replication was determined using a genotype 2a HCV reporter virus expressing secreted Guassia luciferase [42•]. iHLCs inoculated with the reporter HCV virus (HCVcc) had high levels of luciferase activity which was attenuated with a replicase or protease inhibitor [42•]. Supernatants from inoculated cells were transferred onto naïve cells which then demonstrated subsequent infection demonstrating completion of the HCV viral life cycle (through production of infectious HCV virions in iHLCs) [42•]. The developmental stages involved in PSC differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells enable one to determine the step-wise progression at which permissiveness to HCV infection is acquired. Pluripotent stem cells and PSC-derived endoderm are not permissive to HCV infection while PSC-derived hepatocyte-like cells are permissive to HCV infection [44••]. Moreover, knockdown of one of the hepatocyte host factors, cyclophilin A (cypA), in iPSC resulted in impaired infection in iHLCS [44••]. Inoculation of cypA-independent virus restored HCV infection in the cypA mutant lines. Infection of primary human hepatocytes using patient derived HCV serum produces inefficient infection [44••]. In one report, iHLCs inoculated with patient derived HCV (one from a high-titer genotype 1b infection and the other from a patient with a high-titer genotype 1a infection) resulted in robust infections [44••].

HCV Infection in iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells Results in Upregulation of Interferon-Stimulated Genes

Typically hepatoma cell lines have little if any response to HCV infection. In contrast, Schwartz et al. required the use of a Jak inhibitor to dampen the robust antiviral response prior to or as part of HCV infection to enable robust HCV infection with the notable upregulation of IL-28B [42•]. This work was confirmed by Zhou et al. where Jak Inhibitor was shown not only to enhance HCV infection but HCV spread [89]. Further analysis of HCV infection of iHLCs by another group confirmed the upregulation of interferon stimulated genes particularly IRF7 [89], OAS1 [89, 93], RasGRP3 [93], and Trank1 [93].

Creation of Human Liver Chimeric Mice Using iHLCs Enables the Study of HCV Infection in Vivo

Engraftment of iHLCs in vivo to produce human liver chimeric mouse models has been fraught with low efficiencies [15, 94]. In contrast using an optimized hepatocyte differentiation protocol and the MUP-uPA/SCID/bg model, iHLCs were able to engraft and repopulate a liver injury model to produce a human liver chimeric mouse with high levels of human chimerism [90•]. Subsequent infection of these engrafted human liver iHLC chimeric mice with HCV noted that low-dose HCV inoculations were unsuccessful in producing detectable infections while high-dose inoculations (1,000 CID50 per mouse) launched productive and chronic HCV infection [90•]. Chimeric mice were capable of supporting infections of HCV of varying genotypes including genotype 1a, 1b, or 3a. At least 5 % human iHLC chimerism (~450 mcg/mL) was necessary to support HCV infection [90•].

Limitation of iPS-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells to Study Infectious Disease

iHLCs do have some limitations which are pertinent to understand for the scope of experimental study. iHLC generation varies from cell line to cell line with timing or cytokine concentrations necessary for hepatocyte differentiation somewhat variant between pluripotent cell lines. Moreover, the phenotype and function of iHLCs while robust have been shown to closer to that of a fetal hepatocyte rather than an adult hepatocyte [15, 16]. Although this is a challenge particularly in the context of drug metabolism studies, iHLCs have been shown to be a robust tool for the study of a variety of hepatotropic pathogen including HCV infection. In particular, they have been used to dissect out the role of genetic variations in HCV permissiveness, respond to infection with upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes, and have enabled the study of several HCV genotype variants.

Summary

Pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells have revolutionized the ability to study host-pathogen interactions, infectious disease pathogenesis, and genetic susceptibility or resistance to infection. HCV is a hepatotropic pathogen, which has been closely studied and over time a variety of standardized tools were established which resulted in a good understanding of its viral life cycle and ultimate cure. An understanding of the history of the study of the HCV virus serves as a great background for understanding study in the infectious disease and virology communities.

Overall Conclusions

Liver disease is an important global problem and is responsible for 1 million deaths worldwide each year. Infectious disease is a major cause of liver disease specifically and overall is even a greater cause of patient morbidity and mortality responsible for over one-fifth of deaths worldwide. Tools to study human liver disease and infectious disease have been lacking which has significantly hampered the study of liver disease generally and hepatotropic pathogens more specifically. Cellular reprogramming technologies which have culminated in the creation of iPSC represent an unprecedented opportunity to study and treat a variety of human diseases. Pluripotent stem cells are renewable, can be derived from a single donor, and can be efficiently and reproducibly differentiated towards many cell types including ectodermal-, endodermal-, and mesodermal-derived lineages. Traditional studies have been dependent on the use of cell lines which only poorly mimic the cell type of interest if at all and consequently resulted in our limited understanding of key issues in infectious disease and liver biology; (1) What is the impact that a hepatotropic pathogen has on hepatocyte biology, (2) What is the impact that the hepatocyte has on hepatotropic pathogens, (3) How does chronic infection change the long-term behavior of infected hepatocytes. Although this is a brief list, these are fundamental questions that have import beyond the laboratory but have significant clinical impact as it is currently unclear (in the case of HCV) whether patient cure eliminates the complete risks and sequelae of HCV infection. Such questions and concerns will be only addressed with more relevant in vitro and in vivo models of HCV infection.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V et al (2012) Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859):2095–2128

Tai AW, Benita Y, Peng LF, Kim SS, Sakamoto N, Xavier RJ et al (2009) A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe 5(3):298–307

Li K, Chen Z, Kato N, Gale M Jr, Lemon SM (2005) Distinct poly(I–C) and virus-activated signaling pathways leading to interferon-beta production in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 280(17):16739–16747

Schoggins JW, MacDuff DA, Imanaka N, Gainey MD, Shrestha B, Eitson JL et al (2014) Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 505(7485):691–695

Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P et al (2011) A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472(7344):481–485

Dienstag JL (2008) Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med 359(14):1486–1500

Ioannou GN (2013) Chronic hepatitis B infection: a global disease requiring global strategies. Hepatology 58(3):839–843

Lok AS, McMahon BJ (2009) Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology 50(3):661–662

Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z et al (2012) Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife 1:e00049

Gurdon JB, Elsdale TR, Fischberg M (1958) Sexually mature individuals of Xenopus laevis from the transplantation of single somatic nuclei. Nature 182(4627):64–65

• Davis RL, Weintraub H, Lassar AB. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell. 1987 Dec 24;51(6):987-1000 In an era of using heterokaryons to try to better understand the factors that regulate cell fate and phenotype, this report showed that a single transcription factor could convert fibroblasts into myoblasts

Hanna JH, Saha K, Jaenisch R (2010) Pluripotency and cellular reprogramming: facts, hypotheses, unresolved issues. Cell 143(4):508–525

Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K et al (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131(5):861–872

• Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Li J, Battle MA, Duris C, et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology. 2010 Jan;51(1):297-305 PSC differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells had been demonstrated in a variety of earlier reports and found to be a poorly efficient process with generation of only a few cells with the phenotype and function of hepatocytes. In this report, the authors lay out a delineated, developmentally modeled protocol to differentiate PSC in a step-wise (and well described) process into hepatocyte-like cells. These hepatocyte-like cells were rigorously characterized and found to have the morphologic, phenotypic and functional characteristics of hepatocytes

Schwartz RE, Fleming HE, Khetani SR, Bhatia SN (2014) Pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Biotechnol Adv 32(2):504–513

Shan J, Schwartz RE, Ross NT, Logan DJ, Thomas D, Duncan SA et al (2013) Identification of small molecules for human hepatocyte expansion and iPS differentiation. Nat Chem Biol 9(8):514–520

Sterneckert JL, Reinhardt P, Scholer HR (2014) Investigating human disease using stem cell models. Nat Rev Genet 15(9):625–639

Kola I, Landis J (2004) Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discov 3(8):711–715

Collins FS, Varmus H (2015) A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 372(9):793–795

Rashid ST, Corbineau S, Hannan N, Marciniak SJ, Miranda E, Alexander G et al (2010) Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest 120(9):3127–3136

Wilson AA, Ying L, Liesa M, Segeritz CP, Mills JA, Shen SS et al (2015) Emergence of a stage-dependent human liver disease signature with directed differentiation of alpha-1 antitrypsin-deficient iPS cells. Stem Cell Rep 4(5):873–885

Tafaleng EN, Chakraborty S, Han B, Hale P, Wu W, Soto-Gutierrez A et al (2015) Induced pluripotent stem cells model personalized variations in liver disease resulting from alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Hepatology 62(1):147–157

Cayo MA, Cai J, Delaforest A, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Clark BS et al (2012) ‘JD’ iPS cell-derived hepatocytes faithfully recapitulate the pathophysiology of familial hypercholesterolemia. Hepatology 56(6):2163–2171

Ghodsizadeh A, Taei A, Totonchi M, Seifinejad A, Gourabi H, Pournasr B et al (2010) Generation of liver disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells along with efficient differentiation to functional hepatocyte-like cells. Stem Cell Rev 6(4):622–632

Satoh D, Maeda T, Ito T, Nakajima Y, Ohte M, Ukai A et al (2013) Establishment and directed differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells from glycogen storage disease type Ib patient. Genes Cells 18(12):1053–1069

Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A et al (2008) Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell 134(5):877–886

Hansel MC, Gramignoli R, Blake W, Davila J, Skvorak K, Dorko K et al (2014) Increased reprogramming of human fetal hepatocytes compared with adult hepatocytes in feeder-free conditions. Cell Transpl 23(1):27–38

Zhang S, Chen S, Li W, Guo X, Zhao P, Xu J et al (2011) Rescue of ATP7B function in hepatocyte-like cells from Wilson’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells using gene therapy or the chaperone drug curcumin. Hum Mol Genet 20(16):3176–3187

Kim Y, Choi JY, Lee SH, Lee BH, Yoo HW, Han YM (2016) Malfunction in mitochondrial beta-oxidation contributes to lipid accumulation in hepatocyte-like cells derived from citrin deficiency-induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 25(8):636–647

Im I, Jang MJ, Park SJ, Lee SH, Choi JH, Yoo HW et al (2015) Mitochondrial respiratory defect causes dysfunctional lactate turnover via amp-activated protein kinase activation in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 290(49):29493–29505

Urnov FD, Rebar EJ, Holmes MC, Zhang HS, Gregory PD (2010) Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat Rev Genet 11(9):636–646

Wright DA, Li T, Yang B, Spalding MH (2014) TALEN-mediated genome editing: prospects and perspectives. Biochem J 462(1):15–24

Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F (2014) Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell 157(6):1262–1278

Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F (2013) Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8(11):2281–2308

Smith C, Abalde-Atristain L, He C, Brodsky BR, Braunstein EM, Chaudhari P et al (2015) Efficient and allele-specific genome editing of disease loci in human iPSCs. Mol Ther 23(3):570–577

Wang X, Raghavan A, Chen T, Qiao L, Zhang Y, Ding Q et al (2016) CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of pcsk9 in human hepatocytes in vivo-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 36(5):783–786

Ding Q, Strong A, Patel KM, Ng SL, Gosis BS, Regan SN et al (2014) Permanent alteration of PCSK9 with in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Circ Res 115(5):488–492

• Lafaille FG, Pessach IM, Zhang SY, Ciancanelli MJ, Herman M, Abhyankar A, et al. Impaired intrinsic immunity to HSV-1 in human iPSC-derived TLR3-deficient CNS cells. Nature. 2012 Nov 29;491(7426):769-73. Herpes simplex virus causes life-threatening CNS infections which affects primarily children and the elderly and is one of the most common forms of viral encephalitis. In this report, fibroblasts were obtained from patients with defects in resistance to HSV and were found to have UNC-93B deficiency (which is involved in the trafficking of TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 to the endosome). iPS were generated from the UNC-93B-/- cells and were differentiated into neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes. UNC-93B-/- iPSC derived neurons and oligodendrocytes were shown to have significantly reduced TLR3 responses and were more susceptible to HSV-1 infection

Dukhovny A, Sloutskin A, Markus A, Yee MB, Kinchington PR, Goldstein RS (2012) Varicella-zoster virus infects human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons and neurospheres but not pluripotent embryonic stem cells or early progenitors. J Virol 86(6):3211–3218

D’Aiuto L, Di Maio R, Heath B, Raimondi G, Milosevic J, Watson AM et al (2012) Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived models to investigate human cytomegalovirus infection in neural cells. PLoS One 7(11):e49700

Shlomai A, Schwartz RE, Ramanan V, Bhatta A, de Jong YP, Bhatia SN et al (2014) Modeling host interactions with hepatitis B virus using primary and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocellular systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(33):12193–12198

• Schwartz RE, Trehan K, Andrus L, Sheahan TP, Ploss A, Duncan SA, et al. Modeling hepatitis C virus infection using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Feb 14;109(7):2544-8 In this report, the authors showed that induced pluripotent stem cell derived hepatocyte-like cells are permissive to HCV viral entry and support the entire HCV viral life cycle. Moreover the induced pluripotent stem cell derived hepatocyte-like cells responded to HCV infection with upregulation of antiviral and inflammatory pathways. These findings support the use of iPSC and iPSC derived hepatocyte-like cells as models to study infectious disease and the role that genetic variation may play in the pathogen life cycle

Roelandt P, Obeid S, Paeshuyse J, Vanhove J, Van Lommel A, Nahmias Y et al (2012) Human pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes support complete replication of hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol 57(2):246–251

.•• Wu X, Robotham JM, Lee E, Dalton S, Kneteman NM, Gilbert DM, et al. Productive hepatitis C virus infection of stem cell-derived hepatocytes reveals a critical transition to viral permissiveness during differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002617 iPSC were differentiated step-wise into hepatocyte-like cells and at each stage were inoculated with HCV virus to determine at which point the cells became permissive to HCV infection. The authors revealed the specific timing of permissiveness and identified that this correlated with upregulation of miRNA-122. The authors proceeded to manipulate host factors and show their impact on the HCV viral life cycle. This report was one of the first reports to use human iPSC derived hepatocyte-like cells to study the mechanism of pathogen infection

Helsen N, Debing Y, Paeshuyse J, Dallmeier K, Boon R, Coll M et al (2016) Stem cell-derived hepatocytes: a novel model for hepatitis E virus replication. J Hepatol 64(3):565–573

Ciancanelli MJ, Huang SX, Luthra P, Garner H, Itan Y, Volpi S et al (2015) Infectious disease. life-threatening influenza and impaired interferon amplification in human IRF7 deficiency. Science 348(6233):448–453

Sharma A, Marceau C, Hamaguchi R, Burridge PW, Rajarajan K, Churko JM et al (2014) Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as an in vitro model for coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis and antiviral drug screening platform. Circ Res 115(6):556–566

Ng S, Schwartz RE, March S, Galstian A, Gural N, Shan J et al (2015) Human iPSC-derived hepatocyte-like cells support plasmodium liver-stage infection in vitro. Stem Cell Rep 4(3):348–359

Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ (2005) Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis 5(9):558–567

Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP (2006) The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol 45(4):529–538

Edlin BR (2011) Perspective: test and treat this silent killer. Nature 474(7350):S18–S19

Scheel TK, Rice CM (2013) Understanding the hepatitis C virus life cycle paves the way for highly effective therapies. Nat Med 19(7):837–849

Liang TJ, Ghany MG (2013) Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 368(20):1907–1917

Yilmaz H, Yilmaz EM, Leblebicioglu H (2016) Barriers to access to hepatitis C treatment. J inf dev countries 10(4):308–316

Lo Re V, 3rd, Gowda C, Urick PN, Halladay JT, Binkley A, Carbonari DM, et al. Disparities in Absolute Denial of Modern Hepatitis C Therapy by Type of Insurance. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2016 Apr 5

Simmonds P (2004) Genetic diversity and evolution of hepatitis C virus–15 years on. J Gen Virol 85(Pt 11):3173–3188

Bukh J (2004) A critical role for the chimpanzee model in the study of hepatitis C. Hepatology 39(6):1469–1475

Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M (1989) Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 244(4902):359–362

Lohmann V, Bartenschlager R (2014) On the history of hepatitis C virus cell culture systems. J Med Chem 57(5):1627–1642

Kato N, Hijikata M, Ootsuyama Y, Nakagawa M, Ohkoshi S, Sugimura T et al (1990) Molecular cloning of the human hepatitis C virus genome from Japanese patients with non-A, non-B hepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87(24):9524–9528

Tanaka T, Kato N, Cho MJ, Sugiyama K, Shimotohno K (1996) Structure of the 3′ terminus of the hepatitis C virus genome. J Virol 70(5):3307–3312

Tanaka T, Kato N, Cho MJ, Shimotohno K (1995) A novel sequence found at the 3′ terminus of hepatitis C virus genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 215(2):744–749

Kolykhalov AA, Feinstone SM, Rice CM (1996) Identification of a highly conserved sequence element at the 3′ terminus of hepatitis C virus genome RNA. J Virol 70(6):3363–3371

Yanagi M, Purcell RH, Emerson SU, Bukh J (1997) Transcripts from a single full-length cDNA clone of hepatitis C virus are infectious when directly transfected into the liver of a chimpanzee. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(16):8738–8743

Kolykhalov AA, Agapov EV, Blight KJ, Mihalik K, Feinstone SM, Rice CM (1997) Transmission of hepatitis C by intrahepatic inoculation with transcribed RNA. Science 277(5325):570–574

Kaplan G, Racaniello VR (1988) Construction and characterization of poliovirus subgenomic replicons. J Virol 62(5):1687–1696

Lohmann V, Hoffmann S, Herian U, Penin F, Bartenschlager R (2003) Viral and cellular determinants of hepatitis C virus RNA replication in cell culture. J Virol 77(5):3007–3019

Lohmann V, Korner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R (1999) Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285(5424):110–113

Yi M, Bodola F, Lemon SM (2002) Subgenomic hepatitis C virus replicons inducing expression of a secreted enzymatic reporter protein. Virology 304(2):197–210

Lohmann V, Korner F, Dobierzewska A, Bartenschlager R (2001) Mutations in hepatitis C virus RNAs conferring cell culture adaptation. J Virol 75(3):1437–1449

Ikeda M, Yi M, Li K, Lemon SM (2002) Selectable subgenomic and genome-length dicistronic RNAs derived from an infectious molecular clone of the HCV-N strain of hepatitis C virus replicate efficiently in cultured Huh7 cells. J Virol 76(6):2997–3006

Grobler JA, Markel EJ, Fay JF, Graham DJ, Simcoe AL, Ludmerer SW et al (2003) Identification of a key determinant of hepatitis C virus cell culture adaptation in domain II of NS3 helicase. J Biol Chem 278(19):16741–16746

Blight KJ, McKeating JA, Rice CM (2002) Highly permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Virol 76(24):13001–13014

Pietschmann T, Lohmann V, Kaul A, Krieger N, Rinck G, Rutter G et al (2002) Persistent and transient replication of full-length hepatitis C virus genomes in cell culture. J Virol 76(8):4008–4021

Bukh J, Pietschmann T, Lohmann V, Krieger N, Faulk K, Engle RE et al (2002) Mutations that permit efficient replication of hepatitis C virus RNA in Huh-7 cells prevent productive replication in chimpanzees. P Natl Acad Sci USA 99(22):14416–14421

Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao ZJ et al (2005) Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med 11(7):791–796

Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Furusaka A, Tokushige K, Mizokami M et al (2003) Efficient replication of the genotype 2a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon. Gastroenterology 125(6):1808–1817

Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC et al (2005) Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309(5734):623–626

Israelow B, Narbus CM, Sourisseau M, Evans MJ (2014) HepG2 cells mount an effective antiviral interferon-lambda based innate immune response to hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 60(4):1170–1179

Foy E, Li K, Sumpter R Jr, Loo YM, Johnson CL, Wang C et al (2005) Control of antiviral defenses through hepatitis C virus disruption of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(8):2986–2991

Fournier C, Sureau C, Coste J, Ducos J, Pageaux G, Larrey D et al (1998) In vitro infection of adult normal human hepatocytes in primary culture by hepatitis C virus. J Gen Virol 79(Pt 10):2367–2374

Rumin S, Berthillon P, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Trabaud MA, Bizollon T et al (1999) Dynamic analysis of hepatitis C virus replication and quasispecies selection in long-term cultures of adult human hepatocytes infected in vitro. J Gen Virol 80(Pt 11):3007–3018

Rowe C, Goldring CE, Kitteringham NR, Jenkins RE, Lane BS, Sanderson C et al (2010) Network analysis of primary hepatocyte dedifferentiation using a shotgun proteomics approach. J Proteome Res 9(5):2658–2668

Lazar A, Mann HJ, Remmel RP, Shatford RA, Cerra FB, Hu WS (1995) Extended liver-specific functions of porcine hepatocyte spheroids entrapped in collagen gel. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 31(5):340–346

Khetani SR, Bhatia SN (2008) Microscale culture of human liver cells for drug development. Nat Biotechnol 26(1):120–126

Dunn JC, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML (1991) Long-term in vitro function of adult hepatocytes in a collagen sandwich configuration. Biotechnol Prog 7(3):237–245

Ploss A, Khetani SR, Jones CT, Syder AJ, Trehan K, Gaysinskaya VA et al (2010) Persistent hepatitis C virus infection in microscale primary human hepatocyte cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(7):3141–3145

•• Yoshida T, Takayama K, Kondoh M, Sakurai F, Tani H, Sakamoto N, et al. Use of human hepatocyte-like cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for hepatocytes in hepatitis C virus infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011 Dec 9;416(1-2):119-24. In this report the authors were the first to report that induced pluripotent stem cell derived hepatocyte-like cells but not induced pluripotent stem cell were permissive to HCV viral entry and HCV viral replication, offering the possibility to use pluripotent stem cells to study human infection disease

Zhou X, Sun P, Lucendo-Villarin B, Angus AG, Szkolnicka D, Cameron K et al (2014) Modulating innate immunity improves hepatitis C virus infection and replication in stem cell-derived hepatocytes. Stem Cell Rep 3(1):204–214

• Carpentier A, Tesfaye A, Chu V, Nimgaonkar I, Zhang F, Lee SB, et al. Engrafted human stem cell-derived hepatocytes establish an infectious HCV murine model. J Clin Invest. 2014 Nov;124(11):4953-64 The engraftment and repopulation of human liver chimeric mouse models using stem cell derived hepatocyte-like cells has been notoriously inefficient and with low is almost undetectable rates of human chimerism. In this report PSC derived hepatocyte-like cells were transplanted into MUP-uPA-Scid mice and had high levels of human chimerism and evidence of hepatocyte differentiation and enhanced function. The causes of these results as compared to prior reports is not readily discussed or understood but the findings in itself offer the possibility to generate human liver chimeric from any human genetic background. In addition the investigators show that the human liver chimeric mice are permissive to HCV from a variety of genotypes and that there is a minimum threshold of liver chimerism required to sustain chronic HCV infection

• Sourisseau M, Goldman O, He W, Gori JL, Kiem HP, Gouon-Evans V, et al. Hepatic cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of pigtail macaques support hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2013 Nov;145(5):966-9 e7 iPS were generated from pigtail macaques and were differentiated into hepatocyte-like cells. Pigtail macaque hepatocyte-like cells supported HCV infection. Differences in the entry factors were shown to impact overall efficiency of HCV infection and found that differences in pigtail macaque CD81 as compared to human CD81 were largely responsible for these differences. This report is an early report exploiting species differences in pluripotent stem cells to identify species specific factors that impact infection

Luna JM, Scheel TK, Danino T, Shaw KS, Mele A, Fak JJ et al (2015) Hepatitis C virus RNA functionally sequesters miR-122. Cell 160(6):1099–1110

Ignatius Irudayam J, Contreras D, Spurka L, Subramanian A, Allen J, Ren S, et al. Characterization of type I interferon pathway during hepatic differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells and hepatitis C virus infection. Stem Cell Res. 2015;15(2):354-64

Nagamoto Y, Takayama K, Tashiro K, Tateno C, Sakurai F, Tachibana M et al (2015) Efficient Engraftment of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Cells in uPA/SCID Mice by Overexpression of FNK, a Bcl-xL Mutant Gene. Cell Transplant 24(6):1127–1138

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Robert E. Schwartz declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical collection on Application of Stem Cells in Endoderm Derivatives.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, R.E., Bram, Y. & Frankel, A. Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Hepatocyte-like Cells: A Tool to Study Infectious Disease. Curr Pathobiol Rep 4, 147–156 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40139-016-0113-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40139-016-0113-7