Abstract

Tests for dysphagia serve as either assessment or screening tools. To be clinically useful these tools must be reliable, validated with proper psychometric techniques, and feasible. In a previous systematic review, only two screening tools met these criteria from the studies in stroke patients. There are no such systematic reviews assessing the availability and methodological quality of bedside or instrumental diagnostic assessment tools for dysphagia. This systematic review of recent literature identified 13 articles that have targeted development of new dysphagia tools, seven of which related to screening, five to clinical assessment, and one to instrumental assessment. Across all articles, critical appraisal revealed that none of the recent articles addressing screening, clinical or instrumental assessment had sufficient methodological rigor, and therefore readiness, for implementation into clinical practice. To ensure the best in patient care, it is necessary to develop tools with methodological rigor for all patient groups with dysphagia, beyond just screening. Future studies of patients with dysphagia must use prospective controlled study designs and only available tools that are reliable, valid and feasible. The development and testing of any new tools must ensure that they are also reliable, valid and feasible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A test can serve as a screening tool to identify the likelihood of an impairment in a group of patients otherwise not previously identified or as an assessment tool to diagnose the presence, location and severity of an impairment [1]. Diagnostic tests for dysphagia can be further subdivided into: clinical assessment tools administered at the bedside that capture dysphagia signs and symptoms; and instrumental assessment tools that utilize objective technology to measure dysphagia physiology.

Regardless of the purpose of the test, standards are now available to guide the proper psychometric development of screening and diagnostic tests [1, 2•, 3]. A recent systematic review by Schepp et al. [4••] published in 2012 used these guidelines in their review of the literature aimed at identifying existing dysphagia screening protocols for patients with stroke. Accordingly, they argued that screening tools need to be reliable, valid, and feasible. In their review, they identified and critically appraised 35 published screening protocols [4••], of which only two met their aforementioned psychometric criteria with sufficient sample sizes [5, 6].

There are no such systematic reviews assessing the availability and methodological quality of bedside or instrumental diagnostic tools for dysphagia. Our goal for the current study was twofold: to conduct a systematic review of the literature aimed at identifying more recently published screening tools for dysphagia as an up-date to the previous review [4••], and to extend this review to also capture recently published tools that were using either bedside or instrumental technologies to target the assessment of dysphagia impairment in adult patients irrespective of their etiology.

Methods

Operational Definitions

Our search was guided by the following operational definitions, determined a priori: dysphagia, defined as any physiological impairment affecting the oral, pharyngeal and/or upper esophageal phases of swallowing; validity, defined as any statistical assessment of accuracy using either a criterion reference (i.e., sensitivity, specificity, ROC analysis) or correlation with another outcome; and reliability, defined as any statistical assessment of stability either between or within raters (i.e., percent agreement, Kappa, interclass correlation coefficient).

Search Methodology

We conducted electronic searches to identify relevant primary research articles published between January 1, 2012 and July 30, 2013 using the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, AMED, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCRCT). Main search terms included: dysphagia and validity or reliability (see Appendix for full search strategy).

Study Selection

Two independent raters reviewed all citations of the relevant primary research articles. Discrepant ratings were resolved by consensus with a third rater. Citations were excluded if they: had no abstract; included no human participants (animal study); were classified as a tutorial, educational report, or review; used a case series study design (n < 10); involved a population where >10 % of subjects were children (<18 years of age); made no mention of oropharyngeal dysphagia as an outcome measured via screening, clinical, and/or instrumental assessment; were primarily investigating an intervention for dysphagia; or, sought to determine the incidence/prevalence of dysphagia within a given population. All other abstracts were accepted and the cited articles brought to full review.

A full review of each article and conference proceeding was conducted by two independent raters. Discrepant ratings were resolved by consensus with a third rater. During the full article review, studies were excluded if they were deemed to be: a physiology study (i.e., any study investigating the underlying physiology of swallowing, which could be used to inform or create new dysphagia assessment tools); a prediction study (i.e., any study investigating how a given variable predicts dysphagia, or how dysphagia predicts a given variable, via relative risk, odds ratios, or likelihood ratios); an assessment protocol (i.e., any study investigating or seeking to inform or change current assessment protocols); a tool utilization study (i.e., any study looking at the implementation or up-take of a new assessment technique or tool); or a tool effectiveness study (i.e., any study looking at the benefit of a given assessment tool in reducing cost, adverse events, etc.). Conference proceedings were reviewed and excluded according to these same criteria.

Data Extraction

Only full articles that met the inclusion criteria outlined above underwent data extraction. A single rater extracted the following data from each included article: sample size; study population (including etiology, age, and gender); the new assessment tool or technique being validated (index test); and the criterion reference test or correlational outcome used to validate the technique or tool. Data extraction was checked by a second rater and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of each included full article was assessed according to the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) [2•]. The QUADAS-2 is a valid and reliable tool used to evaluate the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies. It includes four domains: patient selection, index test, criterion reference test, and flow and timing.

Results

Literature Retrieval

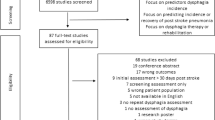

We identified 716 citations pertaining to the development of tools targeting screening or assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia. (Fig. 1). Removal of duplicates resulted in 493 remaining unique citations, of which 421 did not meet our inclusion criteria. Hence, we accepted 72 abstracts for full review. Of these, 29 were peer reviewed journal articles, while the remaining 43 were published abstracts from conference proceedings. Of accepted abstracts, 40 were excluded for reasons detailed in Fig. 1. An additional 19 conference proceedings were only available as abstracts and thus had insufficient details for data extraction or critical appraisal. Thirteen full articles were included in this review and detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Study Characteristics

The 13 full articles were grouped according to the authors’ stated objective to develop dysphagia-specific tools that involved either screening for the presence of dysphagia (n = 7), clinical bedside assessments for symptoms or signs related to swallow physiology (n = 5), or instrumental assessments of the safety and/or efficiency of swallow physiology (n = 1) (Table 1).

Seven articles presented screening tools to identify the increased risk of dysphagia presence. Etiologies included edentulous elderly [7], stroke [8], ALS [9], Parkinson’s disease [10], mixed etiologies [11, 12], and unknown etiologies [13]. Screening methods utilized either clinician testing [7–9, 11–13] or patient self-report [10]. Of the screening methods utilizing clinician testing, two articles [11, 12] used the cough reflex and the remaining articles used one of the following screening methods: laryngeal movement captured by a magnetic sensor [7], water swallows of varying amounts per mouthful [8], varying oral intake of food and liquid textures [9] and capture of an acoustic swallow signal using an accelerometer [13].

Six other articles presented tools for dysphagia assessment either at the bedside [14–18] or using a technical instrument [19]. Of the five articles targeting bedside assessment, etiologies included spinal abnormalities [16, 17], head and neck cancer [15], Duchenne muscular dystrophy [14] and mixed etiologies [18]. Clinical assessment methods utilized patient self-report [14, 15, 17] or clinician testing of oral, oromotor and laryngeal function at the bedside [16, 18]. One article in this review targeted instrumental assessment in patients who had suffered a stroke utilizing an ultrasound device designed to measure tongue thickness [19].

Across all 13 accepted articles, confirmation of dysphagia involved a variety of criterion references: namely, combined repetitive saliva swallowing and digital laryngeal palpation [7], abnormal swallow physiology captured on videofluoroscopy [9, 15, 16], aspiration captured on videofluoroscopy [8, 10, 13], aspiration captured on endoscopy [12], aspiration captured on either videofluoroscopy or endoscopy [11], a live clinical exam [18], functional oral intake [19], and dysphagia related quality of life [17]. However, instead of using a criterion reference, one article [14] presented discriminative validity of self-report captured with the SSQ [20] in patients known to have or not have dysphagia.

Methodological Appraisal

Methodological critical appraisal of the included articles was conducted according to the QUADAS-2 criteria [2] and depicted in Table 2. Of the 13 accepted articles, only three [9, 10, 16] declared the use of consecutive enrolment and did not conduct prior screening for dysphagia. One other article [7] failed to specify the nature of subject recruitment, and the remaining nine introduced serious bias by selecting patients with either suspicion of [8, 11–13] or confirmed dysphagia [14, 15, 17–19].

All accepted articles, except for one [10], described their index testing protocol with enough detail to ensure reproducibility. However, only three articles [11, 17, 18] assessed the inter-rater reliability of the index test. In addition, all but one article [8] described their protocol for criterion reference testing with sufficient detail to ensure reproducibility; yet, only five [10, 11, 13, 15, 18] assessed the inter-rater reliability of the criterion reference. Of these five articles, three [10, 11, 13] defined dysphagia according to airway safety alone (i.e., aspiration) without taking into account swallow efficiency. In general, blinding was not commonly used. In fact, only four articles clearly declared the use of rater blinding in some capacity—three related to their index tests [8, 11, 14] and one related to its criterion reference test [13]—and no article consistently to both tests.

Discussion

This systematic review of recent literature identified 13 articles that targeted development of new dysphagia tools. Of these, seven related to screening, only five to clinical assessment and one to instrumental assessment. Screening protocols identified in this systematic review captured the presence or absence of dysphagia using: (1) devices mounted on the thyroid lamina to record laryngeal elevation [7] or an acoustic swallow signal [13]; (2) concentrations of citric acid introduced into the oropharynx to trigger a cough response [11, 12]; (3) water swallow intake [8] or both water and solid food intake [9] to elicit a cough response and/or oxygen desaturation; and, (4) patient self report to identify problems with oral intake [10]. Similar to the screening protocols, three clinical assessment protocols used either patient self-report [14, 15, 17] or cough response following water intake [16]; however, in contrast to the screening tools, the stated purpose of the assessment protocols was to augment the clinical swallowing assessment. The remaining clinical assessment protocol compared findings from a live versus televised comprehensive exam of the same patients being assessed in both modes simultaneously [18]. The only instrumental assessment protocol that was included in this review used ultrasound measures in the oropharynx to verify dysphagia impairment [19].

Across all articles, critical appraisal identified serious methodological violations regarding: patient selection based on prior knowledge of swallowing status [7, 8, 11–14, 17, 18]; failure to use rater blinding during administration of the index test [7, 13, 16, 19] and/or criterion reference test [8, 9, 16]; and, failure to assess inter-rater reliability for the index [7–10, 12–16, 19] and/or criterion reference [7, 9, 12, 16, 17, 19] tests.

Each of these methodological violations places a study at substantial risk for bias. For example, enrolling patients with known dysphagia and/or a control group without dysphagia may over-estimate the diagnostic accuracy estimate of the new index test [2•], and thereby introduce a bias in its favor [3]. Also, the potential for bias in articles without blinding of both their index and criterion reference tests relates to the subjectivity of interpreting their findings, hence a likely opportunity to exaggerate the diagnostic accuracy [2•]. Furthermore, three articles [10, 11, 13] defined dysphagia narrowly according to airway safety alone without consideration of swallow efficiency. By restricting dysphagia to the absence of safety, milder and more ‘difficult-to-diagnose’ levels of dysphagia may be missed resulting in an overestimation of diagnostic accuracy [2•]. In sum, unfortunately none of the included 13 articles in this review addressing screening, clinical or instrumental assessment had sufficient methodological rigor, and therefore readiness, to justify immediate clinical implementation.

This study serves as an up-date to the systematic review by Schepp [4••]. Given that we identified no new recently published screening tools for dysphagia with adequate psychometric validation, we recommend continued uptake of the findings from Schepp et al. [4••]. According to their review, two available dysphagia screening tools with sufficient sample sizes and sound methodological and psychometric properties are available for clinical use today—the Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR-BSST©) [5] and the Barnes Jewish Hospital Stroke Dysphagia Screen [6].

Recent published work [22] has postulated that no single dysphagia screening tool for patients post-stroke had reached consensus and was ready for clinical implementation. However, from the review by Schepp et al. [4••], two psychometrically tested screening tools do exist. These two screening tools were only published recently, 2009 and 2011, and it is likely too soon to expect high clinical up-take of either tool even though both were supported by high quality evidence. That is, the implementation of evidence is fraught with barriers not necessarily related to its quality; hence, the impetus for future research and funding bodies is to mandate knowledge translation objectives as part of clinical science proposals. [23, 24] Specific to implementation of dysphagia screening, identified barriers have resulted at the level of the institution (willingness to change existing protocols) and of the clinician screener (confidence in being able to execute screening properly). [25] Despite these known barriers to implementation of a dysphagia screening tool, the TOR-BSST© for example is already being utilized by hundreds of speech-language pathologists, in 13 countries and the screening test has been incorporated as part of the Canadian guidelines for stroke care. [21, 26] That is, there is at least one psychometrically sound tool that is emerging with clinical impact on a national (and even global) level. Hopefully the value of the more recent Barnes screening tool will similarly be assessed in the clinical realm.

To ensure the best in patient care, it is critical that we continue to advance science. Our goals should now be to develop tools with the same methodological rigor for all patient groups with dysphagia, and beyond just screening. Although well validated clinical [27] and instrumental [28] assessment tools do exist, this study of the recent literature identified no new additions to this short list. Development of these assessment tools needs to be a future focus among our researchers. For stroke patients there already exist two well validated screening tools for dysphagia [4••] and we identified no recent additions for patients with stroke or other disorders.

Conclusion

In future studies of patients with dysphagia, it is essential to use prospective controlled study designs and only tools that are reliable, valid and feasible. Likewise, the development and testing of any new tools must ensure that they are reliable, valid and feasible.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Streiner DL. Diagnosing tests: using and misusing diagnostic and screening tests. J Pers Assess. 2003;81(3):209–19.

• Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36. This aritcle describes a new tool called the QUADAS-2, supported by the Cochrane group, to conduct critical appraisal for diagnostic accuracy studies. It provides the tool’s conceptual background as well as the methods by which it can be applied to evaluate diagnositc studies. This article is important to researchers conducting systematic reviews.

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD Initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):40–4.

•• Schepp SK, Tirschwell DL, Miller RM, et al. Swallowing screens after acute stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2012;43(3):869–71. This article is a comprehensive review of available dysphagia screening tools, covering up to the start of the year 2012 and thus the time period just before this review. It identifies and critically appraises 35 studies and show that only two screening tools have been developed with sufficient sample sizes and according to the accepted psychometric criteria. This article is important to clinicians pursuing evidence-based practice.

Martino R, Silver F, Teasell R, et al. The Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR-BSST©): development and validation of a dysphagia screening tool for patients with stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(2):555–61.

Edmiaston J, Connor LT, Loehr L, et al. Validation of a dysphagia screening tool in acute stroke patients. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(4):357–64.

Hongama S, Nagao K, Toko S, et al. MI sensor-aided screening system for assessing swallowing dysfunction: application to the repetitive saliva-swallowing test. J Prosthodont Res. 2012;56(1):53–7.

Osawa A, Maeshima S, Tanahashi N. Water-swallowing test: screening for aspiration in stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35(3):276–81.

Paris G, Martinaud O, Hannequin D, et al. Clinical screening of oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with ALS. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;55(9–10):601–8.

Yamamoto T, Ikeda K, Usui H, et al. Validation of the Japanese translation of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Parkinson’s disease patients. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Aspects Treat Care Rehabil. 2012;21(7):1299–303.

Miles A, Moore S, McFarlane M, et al. Comparison of cough reflex test against instrumental assessment of aspiration. Physiol Behav. 2013;118:25–31.

Sato M, Tohara H, Iida T, et al. Simplified cough test for screening silent aspiration. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(11):1982–6.

Steele CM, Sejdic E, Chau T. Noninvasive detection of thin-liquid aspiration using dual-axis swallowing accelerometry. Dysphagia. 2013;28(1):105–12.

Archer SK, Garrod R, Hart N, et al. Dysphagia in Duchenne muscular dystrophy assessed by validated questionnaire. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2013;48(2):240–6.

Govender R, Lee MT, Davies TC, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a patient-reported outcome measure for swallowing after total laryngectomy (SOAL questionnaire). Clin Otolaryngol. 2012;37(6):452–9.

Shem KL, Castillo K, Wong SL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of bedside swallow evaluation versus videofluoroscopy to assess dysphagia in individuals with tetraplegia. PM and R. 2012;4(4):283–9.

Skeppholm M, Ingebro C, Engström T, et al. The Dysphagia Short Questionnaire: an instrument for evaluation of dysphagia: a validation study with 12 months’ follow-up after anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine. 2012;37(11):996–1002.

Ward EC, Sharma S, Burns C, et al. Validity of conducting clinical dysphagia assessments for patients with normal to mild cognitive impairment via telerehabilitation. Dysphagia. 2012;27(4):460–72.

Hsiao M-Y, Chang Y-C, Chen W-S, et al. Application of ultrasonography in assessing oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke patients. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2012;38(9):1522–8.

Wallace KL, Middleton S, Cook IJ. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(4):678–87.

Lindsay PBP, Bayley MM, Hellings CB, et al. Canadian best practice recommendations for stroke care (updated 2008). CMAJ. 2008;179(12):E1–93.

Donovan NJ, Daniels SK, Edmiaston J, et al. Dysphagia screening: state of the art: invitational conference proceeding from the State-of-the-Art Nursing Symposium, International Stroke Conference 2012. Stroke. 2013;44(4):e24–31.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR grants and awards guide. Section 1-A4: knowledge translation. 2011 [July 27, 2012]. Available from: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/22630.html-1-A4..

National Institutes of Health. NIH grants policy statement. Section 8.2.3.1: data sharing policy. 2011 [July 27, 2012]. Available from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/nihgps_2011/nihgps_ch8.htm.

Martino R, Tsang S, Brown A, et al. Screening for dysphagia in stroke survivors: a before and after implementation trial of evidence-based care [abstract]. Dysphagia. 2008;23:429–30.

Casaubon LK, Suddes M, Acute stroke best practices working group 2013. Acute inpatient stroke care. In: Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, Bayley M, Phillips S, Canadian stroke best practices and standards working group, editors. Canadian best practice recommendations for stroke care. Ottawa, ON: Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada; 2013.

Mann G. MASA: the Mann assessment of swallowing ability. Clifton Park: Singular; 2002.

Martin-Harris B, Brodsky MB, Michel Y, et al. MBS measurement tool for swallow impairment–MBSImp: establishing a standard. Dysphagia. 2008;23(4):392–405.

Acknowledgments

R Martino and NE Diamant are developers of the TOR-BSST© and R Martino offers a course focused on the TOR-BSST© for which she does not profit personally.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

R Martino has received research grants from Amgen and a speaker honorarium from Nestle. HL Flowers declares no conflicts of interest; SM Shaw declares no conflicts of interest; NE Diamant declares no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All studies by R Martino involving human subjects were performed after approval by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martino, R., Flowers, H.L., Shaw, S.M. et al. A Systematic Review of Current Clinical and Instrumental Swallowing Assessment Methods. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 1, 267–279 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-013-0033-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-013-0033-y