Abstract

Rising levels of childhood obesity present a serious global public health problem amounting to 7 % of GDP in developed countries and affecting 14 % of children. As such, many countries are investing increasingly large quantities of resource towards treatment and prevention. Whilst it is important to demonstrate the clinical effectiveness of any intervention, it is equally as important to demonstrate cost effectiveness as policy makers strive to get the best value for money from increasingly limited public resources. Economic evaluation assists with making these investment decisions and whilst it can offer considerable support in many healthcare contexts, applying it to a childhood obesity context is not straightforward. Childhood obesity is a complex disease with interventions being multi-component in nature. Furthermore, the interventions are implemented in a variety of settings such as schools, the community, and the home, and have costs and benefits that fall outside the health sector. This paper provides a reflection from a UK perspective on the application of the conventional approach to economic evaluation to childhood obesity. It offers suggestions for how evaluations should be designed to fit better within this context, and to meet the needs of local decision makers. An excellent example is the need to report costs using a micro-costing format and for benefit measurement to go beyond a health focus. This is critical as the organisation and commissioning of childhood obesity services is done from a Local Authority setting and this presents further challenges for what is the most appropriate economic evaluation approach to use. Given that adult obesity is now of epidemic proportions, the accurate assessment of childhood obesity interventions to support public health decision making is critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

The conventional approach to economic evaluation is not useful for the evaluation of childhood obesity interventions. |

Childhood obesity interventions are particularly challenging to evaluate due to the complex nature of the disease and the multi-factorial design of interventions. |

Economic evaluation of childhood obesity interventions needs to take account of the specific needs of decision makers operating in UK Local Authority settings. |

1 Introduction

The rising trend of childhood obesity is a global public health problem. The direct annual costs of obesity and associated health consequences across the EU is 7 % of national health budgets [1], and within the UK National Health Service (NHS) it is over £4 billion, with costs of £16 billion to the wider economy [2]. Determining the most effective and affordable way to reverse the trend of childhood obesity is a challenge due to complex causal pathways, and the multi-component nature of prevention and treatment interventions.

There are serious health consequences from being overweight as a child. As well as the increased risk of being overweight and associated co-morbidities in adult life, there are reports of childhood obesity causing type 2 diabetes [3], early puberty [4, 5], cardiovascular problems [6], sleep apnoea [7], skin infections [8], musculoskeletal problems [9], as well as respiratory problems such as asthma [10]. As well as the health consequences of being overweight, research findings have also reported wider psychosocial problems such as reduced self-esteem [11], lower quality of life [12], anxiety and depression in adolescents [12, 13], lower educational attainment [14] and social isolation [15].

Obesity is now a global public health problem with one in three adults being overweight or obese [16]. The US has the highest rates of childhood obesity [17, 18], and the UK has one of the highest rates in Europe with an estimated 29 % of 2–15 year olds being overweight and obese [19].

This is a societal problem which requires a societal solution. Much has been written about the causes of obesity. Philipson and Posner (2008) summarised a decade of research on the economics of obesity, presenting the arguments from both a positive (understanding determinants of obesity) and a normative (should governments intervene) perspective [20]. The economic climate means that, for many countries, resources are scarce and therefore decision makers need to prioritise spending and invest in initiatives that offer the best value for money. Economic evaluation is now well established as a means to aid public resource allocation decisions. Over the last three decades, particularly in the UK, the methods of economic evaluation have evolved to what is now regarded as a ‘conventional’ approach, driven by the need for policy makers such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK and the US Panel of Cost-Effectiveness to achieve consistency and transparency with decision making.

This paper extends the work of Philipson and Posner by analysing the unique features of childhood obesity through an economics lens and discussing the strengths and weaknesses of the conventional application of economic evaluation in this context from a UK perspective. It assesses the evaluative framework for economic evaluation, taking into account the complex nature of the condition, the different needs of decision makers, and the particular challenges of conducting economic evaluation within a paediatric population.

2 Evaluation of Childhood Obesity Interventions

Relative to the number of published evaluations of the effectiveness of childhood obesity interventions, there are very few formal economic evaluations reported [21]. In the latest Cochrane review of 55 studies reporting evaluations of childhood obesity interventions published up to 2010, it was found that none contained a formal economic evaluation [22]. Furthermore, among the few evaluations that have been reported, there is considerable variation in the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [23] caused in part by different data sources used, alternative model structures and assumptions made during the analyses. This makes it difficult to draw any conclusions about comparative cost effectiveness across different types of interventions. A more recent review of 22 economic evaluations published in 2015 found that 18 interventions were either ‘dominant’ or cost effective, but in terms of perspective, all of these evaluations measured outcomes in health-related units using either the QALY (quality-adjusted life-year), the DALY (disability-adjusted life-year) or a natural health unit such as body mass index (BMI) or waist circumference, and there was an overwhelming focus on healthcare costs [24]. Virtually all reported economic evaluations of childhood obesity interventions adhere to the conventional health service/personal social care perspective and none report from the societal perspective.

To assist decision making, economic evaluations should be methodologically comparable and of high quality [25] and in the UK, the conventional reference case for health technology assessment is to measure costs from a health/social care perspective and to measure benefits that accrue to patients in QALYs [26]. The benefit of having a reference case for economic evaluation is the consistency in methods facilitating judgements about the differential cost effectiveness of interventions across different diseases and clinical settings.

When treatments fit neatly within the healthcare sector and thus have clear healthcare costs and health benefits, the reference case for economic evaluation is a powerful aid for the process of decision making. The situation becomes more complex when the costs (and benefits) of interventions fall both within and outside the healthcare sector, which is often the case for public health contexts [27–29] and, in particular, childhood obesity interventions. This research context is further complicated by the mixture of how childhood obesity services are commissioned and implemented. Within the UK, many services are funded by local authorities whilst others are either privately or charity funded. Services can be implemented in a variety of settings such as within schools, private homes, leisure centres or in community settings such as local parks. This mixture of how services are organised makes it difficult to track expenditure and to determine causal effect. Methods akin to a natural experimental approach such as difference-in-differences analysis or regression discontinuity have been applied, and these methods are useful for when there is no control over data collection and for when routinely collected data can be used to track exposure and control for potential confounders [30]. For further detail about these methods, please refer to Wagner et al. [5]. What this paper focuses on, however, is a discussion of methods for economic evaluation when there is an opportunity to influence data collection. It explicitly considers the perspective for commissioning of childhood obesity services in the UK which takes place within public health teams located in local authority settings. It discusses aspects of the reference case for economic evaluation and highlights where it is not always appropriate for this context, making suggestions for how evaluations could be reported under the assumption that these suggestions better fit the needs of the decision maker.

3 Guidelines for Economic Evaluation

In recognition of the wider context, the NICE in the UK updated its guidance for economic evaluations within a social care and public healthcare setting in 2013 [26]. This guidance recommends the use of the reference case wherever possible but also recognises the significance of non-public sector costs and carer outcomes and allows for alternative methods such as cost–benefit analysis and measures of capability (wider wellbeing) outcomes. Overall, the guidance allows for the consideration of non-health sector costs and benefits but still supports the use of the reference case due to the need for transparency and consistency with decision making. Adlard et al. [31] provides an overview of how NICE’s guidance has evolved over time, particularly with respect to paediatric evaluations.

For the economic appraisal of general (usually non-health) public sector projects, the UK Treasury guidance [32] takes a much wider perspective and recommends methods akin to cost–benefit analysis whereby all costs and benefits are accounted for and measured in monetary values. Projects are then assessed according to their net present value. The guidance highlights the distinction between reporting accounting costs to understand cash flows and resource costs, and reporting opportunity costs which reflect the wider costs and benefits of projects. The guidance also recommends that implementation and monitoring costs are included and that any substantial differences in costs between population subgroups are highlighted. Treasury guidance also supports the inclusion of ‘social value’, recognising that public sector commissioners need to consider ‘social impact’, as set out in the UK Public Services (Social Value) Act in 2012. This requires all commissioners to consider the economic, social and environmental value when spending money on public service contracts and to, where possible, select services that can add value to society.

Given that childhood obesity commissioning takes place in a local government setting, both sets of guidance (Treasury and NICE) for evaluation are relevant.

4 Recommendations for Economic Evaluation of Childhood Obesity Interventions

Ultimately, the decision of what perspective to adopt for economic evaluation is a normative one driven by the information needs of decision makers. Local authorities have a remit to improve the health and wellbeing of local populations and to reduce inequalities in health [33]; therefore, the perspective needs to be broader than just health and include a wider set of costs and benefits.

4.1 Measuring Costs

Childhood obesity interventions tend to be complex multi-component interventions delivered in school and community settings and this creates challenges for costing as the measurement of resource use requires methods that are not routinely used under the healthcare perspective. Ideally, costs should be measured using a micro-costing approach, providing in-depth, transparent, bottom-up cost data [34, 35]. This serves to facilitate future economic analyses as researchers can accurately extract and adapt data to fit within their local context. Where possible, all resource use should be measured to reflect a societal cost [36], outlining how each cost item fits within each sector—whether that is the health, education, transport or a wider community sector. This also helps to understand the flow of expenditure, tracking how investments in one sector (e.g. education) will realise benefits in another sector (e.g. health) [37]. Parents/guardians participating in the intervention also incur time and productivity costs and these personal costs should be considered and included within a broader perspective.

It is rare for an economic evaluation to include implementation costs as often an assumption of steady state is adopted and, although it provides information about the cost effectiveness of multiple interventions under the assumption that they are operating at their full effectiveness potential, it does not provide information on the overall impact on annual budgets. Using decision-analytic modelling to extrapolate costs (and effects) into the future provides a powerful tool to estimate the long-term cost effectiveness; however, the inclusion of cost offsets (where the intervention cost is offset by future healthcare savings from obesity prevention) provides little guidance on the budgets required to implement and support the interventions. So, a parallel costing analysis should be done for organisations to fully understand the implementation costs. To understand the overall budget impact, operating costs, and the short- and long-term cost effectiveness, it is recommended that costs be reported in several ways. This need is in line with the UK Treasury guidance and is articulated in the Carter et al. study that measured the cost effectiveness of 13 obesity prevention interventions in children [38], which recommends that costs should be reported as ‘gross costs’ (ignoring cost offsets), ‘net costs’ (including cost offsets to understand long-term achievability) and ‘net cost per child’ to give an indication of reach within the population. This is as well as cost effectiveness to explicitly link incremental costs with incremental outcomes achieved by the intervention, in comparison with an alternative. These costs therefore need to be clearly articulated with the up-front implementation costs included and any ongoing monitoring costs incorporated.

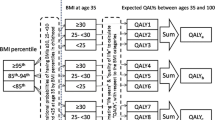

The relevant costs to include will also be driven by the time period for analyses. Local authorities operate within tightly regulated annual budget cycles that fit within a 4- to 5-year planning cycle [39]. This means that decision makers are interested in short-term (annual), as well as 5-year budget impact. This fits with the UK Treasury guidance for cost–benefit analysis which suggests a 5-year assessment [32]. However, to make the case for investment, local authorities also require information on long-term, lifetime cost effectiveness, as a large part of the gain from preventing the onset of childhood obesity is not realised until adulthood. Extrapolating costs (and benefits) into the future therefore requires an understanding of the long term effectiveness of interventions and any assumptions need to be fully explored through sensitivity analysis. If adopting a societal approach and extrapolating over the life course into adulthood then future productivity gains from preventing obesity (e.g. the effects of obesity upon presenteeism and absenteeism) become relevant and therefore should be included in the cost-effectiveness results. To fit with these needs of the decision maker, the time period should be varied and presented for 1, 5, 10, 20 and 50 years.

4.2 Measuring Outcomes

To date, economic evaluations of childhood obesity interventions have measured outcomes in health-related units. Aside from the general challenges of conducting economic evaluation of child health interventions [40], there exists two significant challenges:

-

1.

The impact of being overweight on general wellbeing that goes beyond a health-related measure of quality of life;

-

2.

The impact upon wider family and friends from preventing overweight in children.

The normative question of whether these effects should be included within the economic evaluation is down to the chosen perspective for the analyses but it is worth noting that childhood obesity interventions are often funded from a public health budget and therefore effects that go beyond a strict health perspective should be considered.

A linked theoretical paradigm is the co-production of health and wellbeing and this is emerging as a new model for the way health care is managed in the UK [41]. This theoretical model rests on the notion that individuals play a key role towards achieving good health outcomes beyond the contribution of healthcare [42]. It is particularly relevant to the prevention of childhood obesity with most interventions designed to encourage positive behaviour change in the form of improved eating habits and increased physical activity. Within the UK, however, wellbeing data for children under the age of 11 years are not routinely collected [43]. Middle childhood (6–12), is a period that is particularly apt for obesity prevention, a stage in life when children’s social and emotional development, health and wellbeing, and key contextual assets have been identified as important for developmental outcomes [44]. This suggests that obesity prevention initiatives that holistically address children’s wellbeing may more successfully reduce childhood obesity rates rather than interventions with a narrower health focus and fits well with the latest steer from the literature that obesity should be regarded as less of a ‘health’ problem and be viewed in a much wider sense. Since there is widespread agreement that childhood obesity is caused by the complex interplay between individual and family behaviour, which is further influenced by societal determinants of health and wellbeing such as education, social status and commercial food marketing campaigns, then it follows that prevention initiatives should have a focus that is beyond just health. For economic evaluation to fit within this framework it therefore needs to include a measure that goes beyond health.

Despite this, all reported evaluations thus far have reported effectiveness using either QALYs or DALYs, or natural health units. With respect to weight outcomes, whilst this provides valuable information for the comparison of competing weight-management services, they do not facilitate comparisons across programmes of services within other clinical contexts such as smoking or alcohol addiction. Furthermore, NICE guidance for measuring QALYs in children is not as clear as with adults and specifies that consideration should be given to an instrument that has been designed specifically for use in children [26]. The current relevant instruments to consider, therefore, are either the Health Utilities Index (HUI) [45], the Child Health Utility-9 Dimension (CHU-9D) [46], the EuroQoL EQ-5D-Y [47], or the A-QoL-6D for adolescents [48].

The HUI, a family of preference-based instruments that comprises two versions, HUI2 and HUI3, contains a scoring system for children aged 5 years and older and a scoring system is under development for children aged 3–5 years. Several studies have reported on the psychometric properties of the instruments when used in children [49, 50]. The HUI2 has six dimensions (sensation, mobility, emotion, cognition, self-care, pain) (excluding the original HUI2 dimension of fertility) with four to five levels per dimension, and the HUI3 has eight dimensions (vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, pain) with five to six levels per dimension. The CHU-9D instrument has been designed using extensive thematic content analysis of qualitative interview data with children and contains nine dimensions, each with five levels (worried, sad, pain, tired, annoyed, school work, sleep, routine, activities). It was originally developed for children aged 7–11 years but more recently has been used in adolescents [49]. The commonly used adult EQ-5D instrument has been adjusted for use in children with changes made to the wording of the five dimensions (walking, looking after one self, usual activities, pain, worried or sad). At present, there is no value set available for the EQ-5D-Y and the EuroQoL group do not recommend the use of the adult value set for the EQ-5D-Y [50]. The A-QoL has been adapted for use in adolescents and covers six domains: independent living, mental health, coping, relationships, pain and senses. This instrument has been applied in an Australian setting with overweight adolescents reporting lower quality of life [51].

In younger children, with respect to the psychometric quality of these instruments for differentiating between weight-status groups, there is conflicting evidence. Using the CHU-9D in 5- to 6-year olds, Frew et al. found no evidence of a relationship between weight and utility-based quality of life [52]; a similar result was found by Belfort et al., who used the HUI-2 in children aged 5–18 years [53]. However, a recent study by Chen et al. [54] found a significant negative relationship between overweight and quality of life when using the CHU-9D in 10-year olds. There is clearly a lack of consensus regarding the association between obesity and quality of life when measured by these preference-based instruments in children and this adds another layer of uncertainty when measuring the effectiveness of obesity interventions in this age group.

Accepting the principle that the prevention of childhood obesity requires a broader focus on child wellbeing raises the question of whether the CHU-9D, A-QoL, or the HUI2 and HUI3 are adequate instruments alone for the economic evaluation. It is worth noting that all these instruments have been developed with the objective of measuring health-related quality of life and not wellbeing. None, for example, collect data on social determinants, or life beyond physical and emotional quality of life such as the child’s relationship with peers or family members or how leisure time is used.

Other condition-specific instruments have been developed for children/adolescents to capture aspects of quality of life known to be affected by weight, such as the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Kids (IWQOL-Kids) [55], Sizing Me Up [56] and the Youth Quality of Life Instrument-Weight Module (YQOL-W) [57], and whilst these instruments have value for measuring effectiveness for obesity interventions, they are limited for economic evaluation when there is a requirement to produce information for decision makers with responsibility for allocating budgets across multiple public health programmes. Wellbeing measures can facilitate these comparisons across programmes.

Understanding how wellbeing predicts childhood obesity and how these measures can and should be used as a complement to QALYs within an economic evaluation, and within the decision-making context, would help to provide further insight into appropriate methods for the economic evaluation of childhood obesity services.

A further issue to consider linked to the perspective for the analysis is whether to include family member benefits within the evaluation. Children, for example, have a particularly strong active dependent relationship with parents/guardians that can lead to significant positive/negative externalities from obesity interventions; for example, nutrition advice provided to children at school will filter into the household and lead to a positive change in eating behaviour for the whole family. The methodological issues to consider are not unique to childhood obesity as they also exist within other contexts such as whether positive/negative carer externalities should be included and those of ‘network’ members within end-of-life care. The size of the family can be measured in both health-related and wellbeing units, then included in the evaluation and subjected to a sensitivity analysis. The size of the family effect is directly linked to the size of the family unit so, to avoid potential methodological problems of favouring interventions that target larger family units (thus producing a larger effect), a mean intervention-specific family effect can be assumed for every child.

Furthermore, while important developments have been made for economic evaluation to explicitly consider equity [58], it is still rare to see this applied routinely, and in the context of childhood obesity it is, as yet, non-existent. This is particularly relevant as, within the UK, South Asian children have a higher prevalence of obesity compared with white children (23 vs 18 % in 10- to 11-year olds) [59] and childhood obesity is more marked in deprived populations [60]. Decision makers may therefore choose to divert funds from a universal approach towards a targeted approach to prevent obesity in these population subgroups. To help provide evidence to support such a decision, evaluations should whenever possible follow UK Treasury advice and account for distributional impact so that decision makers can understand the efficiency/equity trade off.

4.3 Discounting

It is standard practice in cost-effectiveness evaluations to apply a discount rate of 3–5 % on future costs and outcomes [61]. In a UK context, both NICE and the Treasury recommend a discount rate of 3.5 % for both costs and outcomes [26, 32]. For childhood obesity interventions, the impact of discounting leads to future health gains being ‘devalued’ and this is somewhat counter-intuitive. However, failure to discount would result in potentially very large benefits and to facilitate decision making, the practice of discounting means that costs and benefits can be compared as if they occurred at the same time [61].

The theory of discounting is linked to individual preferences for something now as opposed to the future but it is not clear whether that time preference rate should extend to the consideration of societal health benefits and if the social discount rate is an aggregation of several individual discount rates [62]. It is outside the scope of this paper to present a full account of the literature on the theory and practice of discounting but it is important to note that the debate on whether future health benefits should be discounted, and at the same rate as costs, is ongoing, and that the chosen discount rate will have a large impact on the cost effectiveness of childhood obesity interventions. It is good practice to highlight the sensitivity of cost-effectiveness values to chosen discount rates in the analysis.

5 Discussion

This paper has discussed methods for the economic evaluation of childhood obesity intervention within the context of a UK setting where responsibility for public health sits within local government. Nevertheless, many of the issues raised are relevant to other country settings with similar decision-making responsibilities such as within the US, where local and state health departments are responsible for public health; or within China where the financial burden caused by obesity is putting enormous pressure on public health departments [63]. Obesity is a complex condition caused by interactions of genetic, environmental, psychological and behavioural factors [64, 65]. Interventions to tackle obesity therefore need to be equally complex and multi-factorial [18, 64], and the methods for economic evaluation need to adapt accordingly.

This paper suggests broadening the evaluative space to go beyond the traditional health focus and to include costs and effects across multiple sectors. As with the reporting of all economic evaluations, the methods need to be clear and transparent. If the intervention is found to be effective in the short term, then long-term extrapolation should also consider family health externalities, wider wellbeing effects and long-term productivity gains. Long-term decision-analytic modelling could estimate the returns from investment such as education attainment, economic productivity, and wellbeing gains. Indeed, recent evidence has shown support from local authorities for methods suited to estimating return on investment incorporating multiple sector costs and benefits [62, 66].

Given the emerging evidence linking wellbeing gains with health improvements, it is advised that a wider evaluative space for the measurement of economic benefit of childhood interventions is used. Tools for this purpose exist [67] and with more researchers broadening their thinking beyond the QALY, this will help to progress the development of these measures within children yet further and help to understand how these measures can be used within an economic framework for decision making. This fits well with the public health decision-maker needs which are also broader than just health.

It is only within the last 5 years in the UK that commissioning responsibilities have shifted from the health service to local authorities and the methods of economic evaluation need to adapt to fit with this changing context. The challenges of conducting economic evaluation within a public health context are apparent in the childhood obesity setting but particularly pronounced; therefore, there is a need for an improved understanding of local authority decision-maker needs and how the methods and reporting of economic evaluations can be adapted to fit with those needs.

References

European Commission. Ten key facts about nutrition and obesity. European Commission. 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/nutrition/documents/10keyfacts_nut_obe.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2015.

McPherson K, Marsh T, Brown M. Tackling obesities: future choices - modelling future trends in obesity and the impact on health. London: Foresight Programme of the Government Office for Science; 2007. http://www.foresight.gov.uk/Obesity/14.pdf. Accessed 4 Oct 2015.

Diabetes UK. Diabetes in the UK 2012. Key statistics on diabetes. 2012. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/diabetes-in-the-uk-2012. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

Ahmed ML, Ong KK, Dunger DB. Childhood obesity and the timing of puberty. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:237–42.

Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang MS, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:299–309.

Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardio vascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150:12–7.

Narang I, Mathew JL. Childhood obesity and obstructive sleep disorder. J Nutr Metab. 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/134202.

Jabbour SA. Cutaneous manifestations of endocrine disorders: a guide for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:315–31.

Daniels SR. Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes. 2009;33:S60–80.

Egan K, Ettinger A, Bracken M. Childhood body mass index and subsequent physician-diagnosed asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:121. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-13-121.

Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Social marginalisation of overweight children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:746–52.

Griffiths LPT, Hill AJ. Self-esteem and quality of life in obese children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:282–304.

Rofey D, Kolko R, Losif A-M, Silk JS, Bost JE, Feng E, et al. A longitudinal study of childhood depression and anxiety in relation to weight gain. Child Pscyhiatry Human Dev. 2009;40:517–26.

Caird J, Kavanagh J, Oliver K, Oliver S, O’Mara A, Stansfield C, et al. Childhood obesity and educational attainment. A systematic review. EPPI Centre Report Number 1901. 2016. University of London.

Falkner NH, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Jeffery RW, Beuhring T, Resnick MD. Social, educational, and psychological correlates of weight status in adolescents. Obes Res. 2001;9:32–42.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margano C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Frois C, Cremieuz P-Y. For a step change to curb the obesity epidemic. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:613–7.

Hurby A, Hu FB. The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:678–89.

Public Health England. Obesity and Health. 2015. http://www.noo.org.uk/NOO_about_obesity/child_obesity/UK_prevalence. Accessed 29 Sept 2015.

Philipson T, Posner R. Is the obesity epidemic a public health problem? A decade of research on the economics of obesity. 2008. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 14010.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obesity: the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. London: NICE; 2006.

Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Brown T, Campbell TJ, Gao Y, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children (Review). Issue 12. 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration.

John J, Wolfenstetter SB, Wenig CM. An economic perspective on childhood obesity: recent findings on cost of illness and cost effectiveness of interventions. Nutrition. 2012;28:829–39.

Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, Hall KD, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, et al. Child and adolescent obesity: part of the bigger picture. Lancet. 2015;385:2510–20.

Langer A. A framework for assessing Health Economic Evaluation (HEE) quality appraisal instruments. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:253. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-253.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: NICE; 2013.

Payne K, McAllister M, Davies LM. Valuing the economic benefits of complex interventions: when maximising health is not sufficient. Health Econ. 2013;22:258–71.

Trueman P, Anokye NK. Applying economic evaluation to public health interventions: the case of interventions to promote physical activity. J Public Health 2013;35(1):32–9. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fds050.

Weatherly H, Drummond M, Claxton K, Cookson R, Ferguson B, Godfrey C, et al. Methods for assessing the cost-effectiveness of public health interventions: key challenges and recommendations. Health Policy. 2009;93:85–92.

Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D, Haw S, Lawson K, MacIntryre S, et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new medical research council guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:1182–6.

Adlard N, Kinghorn P, Frew E. Is the UK NICE ‘reference case’ influencing the practice of pediatric quality-adjusted life year measurement within economic evaluations? Value Health. 2014;17:454–61.

HM Treasury. The green book. Appraisal and evaluation in central government. London: TSO; 2011 (Ref Type: Report).

Department of Health. The public health role of local authorities. Public Health in Local Government. http://www.ch.gov.uk/publications. Gateway Reference: 17876. 12.

Charles JM, Edwards RT, Bywater T, Hutchings J. Micro-costing in public health economics: steps towards a standardised framework, using the incredible years toddler parenting program as a worked example. Prev Sci. 2013;14:377–89.

McIntosh E, Clarke PM, Frew EJ, Louviere JJ. Applied methods of cost-benefit analysis in health care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Johannesson M, Jonsson B, Jonsson L, Kobelt G, Zethraeys B. Why should economic evaluations of medical innovations have a societal perspective? Office of Health Economics Briefing Paper [No. 51]. 2009.

Department of Communities and Local Government. National Statistics. Local Government Financial Statistics England. 14. London.

Carter R, Moodie M, Markwick A, Magnus A, Vos T, Swinburn B, et al. Assessing cost effectiveness in obesity (ACE-Obesity): an overview of the ACE approach, economic methods and cost results. BMC Public Health. 2009. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-419.

Birmingham City Council. Business Plan 2015+. Budget Report and Resource Plan. 2015.

Ungar W. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Alakeson V, Bunnin A, Miller C. Coproduction of health and wellbeing outcomes: the new paradigm for effective health and social care. 2013. OPM Connects, Insight Policy and Practice.

Dentzer S. Rx for the ‘Blockbuster Drug’ of Patient Engagement. Health Aff 2013;32(2):202. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0037.

Department of Health. A compendium of factsheets: wellbeing across the lifecourse. London: Department of Health; 2014.

Guhn M, Janus M, Hertzman C. The early development instrument: translating school readiness assessment into community actions and policy planning. Early Educ Dev. 2007;18:369–74.

Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G. The Health Utilities Index (HUI): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:54. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-54.

Stevens K. Developing a descriptive system for a new preference-based measure of health-related quality of life research. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1105–13.

Willie N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burstrom K, Gulia K, Devlin N, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:886.

Moodie M, Richardson J, Rankin B, Iezzi A, Sinha K. Predicting time-trade-off health state valuations of adolescents in four Pacific countries using the Assessment of Quality-of-Life (AQoL-6D) instrument. Value Health. 2010;13:1014–27.

Ratcliffe J, Stevens K, Flynn T, Brazier J, Sawyer M. An assessment of the construct validity of the CHU9D in the Australian adolescent general population. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:717–25.

Reeman M, Janssen B, Oppe M, Kreimeier S, Greiner W. EQ-5D-Y User Guide. Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-Y instrument. Version 1. 2014. The EuroQoL Group.

Keating C, Moodie M, Richardson J, Swinburn B. Utility-based quality of life of overweight and obese adolescents. Value Health. 2011;14:752–8.

Frew E, Pallan M, Lancashire E, Hemming K, Adab P. Is utility-based quality of life associated with overweight in children? Evidence from the UK WAVES randomised controlled study. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:211. doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0526-1

Belfort M, Zupancic J, Riera K, Runer J, Prosser L. Health state preferences associated with weight status in children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr 2011. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-11-12.

Chen G, Ratcliffe J, Olds T, Magarey A, Jones M, Leslie E. BMI, health behaviors, and quality of life in children and adolescents: a school-based study. Pediatrics 2014. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0622.

Kolotkin RL, Zeller M, Modi AC, Samsa GP, Quinla NP, Yanovski JA, et al. Assessing weight-related quality of life in adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:448–57.

Zeller MH, Modi AC. Development and initial validation of an obesity specific quality of life measure for children: sizing me up. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:1171–7.

Conway K, Patrick D, Acquadro C, Fuller DS. Translatability of the youth quality of life instrument—weight module. Value Health. 2013;16:A5.

Wailoo A, Tsuchiya A, McCabe C. Weighting must wait: incorporating equity concerns into cost-effectiveness analysis may take longer than expected. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:983–9.

Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. 2004;5(Suppl):4–85.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. National Child Measurement Programme—England, 2013–2014 [NS]. National Statistics. 2014.

Smith DH, Gravelle H. The practice of discounting in economic evaluations of health care interventions. J Technol Assess Health Care. 2001;17:243.

Acharya A, Murray A. Rethinking discounting of health benefits in cost-effectiveness analysis. 2000. Institute of Development Studies discussion paper. University of Sussex.

Cremieux P. Policy makers views of obesity-related challenges around the world. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:619–28.

Kopelman PG. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature. 2000;404:635–43.

Yang W, Kelly T, He J. Genetic epidemiology of obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:49.

Marks L, Hunter DJ, Scalabrini S, Gray J, McCafferty S, Payne N, et al. The return of public health to local government in England: changing the parameters of the public health prioritization debate? Public Health 2015;129(9):1194–203.

Schonert-Reichl KA, Guhn M, Gadermann AM, Hymel S, Sweiss L, Hertzman C. Development and validation of the middle years development instrument (MDI): assessing children’s well-being and assets across multiple contexts. Soc Indic Res. 2013;114:345–69.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of (financial or non-financial) interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frew, E. Economic Evaluation of Childhood Obesity Interventions: Reflections and Suggestions. PharmacoEconomics 34, 733–740 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0398-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0398-8