Abstract

Introduction

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard within evidence-based research. Low participant accrual rates, especially of underrepresented groups (e.g., racial-ethnic minorities), may jeopardize clinical studies’ viability and strength of findings. Research has begun to unweave clinical trial mechanics, including the roles of clinical research coordinators, to improve trial participation rates.

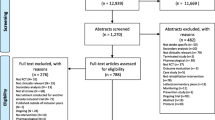

Methods

Two semi-structured focus groups were conducted with a purposive sample of 29 clinical research coordinators (CRCs) at consecutive international stroke conferences in 2013 and 2014 to gain in-depth understanding of coordinator-level barriers to racial-ethnic minority recruitment and retention into neurological trials. Coded transcripts were used to create themes to define concepts, identify associations, summarize findings, and posit explanations.

Results

Barriers related to translation, literacy, family composition, and severity of medical diagnosis were identified. Potential strategies included a focus on developing personal relationships with patients, community and patient education, centralized clinical trial administrative systems, and competency focused training and education for CRCs.

Conclusion

Patient level barriers to clinical trial recruitment are well documented. Less is known about barriers facing CRCs. Further identification of how and when barriers manifest and the effectiveness of strategies to improve CRCs recruitment efforts is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1624–32.

Lamas GA, Pfeffer MA, Hamm P, Wertheimer J, Rouleau J-L, Braunwald E. Do the results of randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular drugs influence medical practice? N Engl J Med. 1992;327(4):241–7.

Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1929–35.

Haidich A-B, Ioannidis JP. Patterns of patient enrollment in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(9):877–83.

Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, Leese B. Why ethnic minority groups are under-represented in clinical trials: a review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2004;12(5):382–8.

Roberts J, Waddy S, Kaufmann P. Recruitment and retention monitoring: facilitating the mission of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). JVIN. 2012;5(1.5).

Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Green EM, McLeod HL, Goldberg RM. Racial differences in advanced colorectal cancer outcomes and pharmacogenetics: a subgroup analysis of a large randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(25):4109–15.

Chen MS, Lara PN, Dang JH, Paterniti DA, Kelly K. Twenty years post-NIH revitalization act: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual. Cancer. 2014;120(S7):1091–6.

NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, Subtitle B, Part 1, Sec 131-133, June 10, 1993.

Lai GY, Gary TL, Tilburt J, Bolen S, Baffi C, Wilson RF, et al. Effectiveness of strategies to recruit underrepresented populations into cancer clinical trials. Clinical Trials (London, England). 2006;3(2):133–41.

Branson RD, Davis K, Butler KL. African Americans’ participation in clinical research: importance, barriers, and solutions. Am J Surg. 2007;193(1):32–9.

George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e16–31.

Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–42.

Daverio-Zanetti S, Schultz K, del Campo MAM, Malcarne V, Riley N, Sadler GR. Is religiosity related to attitudes toward clinical trials participation? J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(2):220–4.

Rivers D, August EM, Sehovic I, Green BL, Quinn GP. A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans’ participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):13–32.

Giuliano AR, Mokuau N, Hughes C, Tortolero-Luna G, Risendal B, Ho RC, et al. Participation of minorities in cancer research: the influence of structural, cultural, and linguistic factors. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8):S22–34.

Kurt A, Semler L, Jacoby JL, Johnson MB, Careyva BA, Stello B et al. Racial differences among factors associated with participation in clinical research trials. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2016:1–10.

Watson JM, Torgerson DJ. Increasing recruitment to randomised trials: a review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):1.

Foy R, Parry J, Duggan A, Delaney B, Wilson S, Lewin-van den Broek N, et al. How evidence based are recruitment strategies to randomized controlled trials in primary care? Experience from seven studies. Fam Pract. 2003;20(1):83–92.

Pelke S, Easa D. The role of the clinical research coordinator in multicenter clinical trials. J Obstet, Gynecol, Neonatal Nurs. 1997;26(3):279–85.

Davis AM, Hull SC, Grady C, Wilfond BS, Henderson GE. The invisible hand in clinical research: the study coordinator’s critical role in human subjects protection. J Law, Med Ethics. 2002;30(3):411–9.

Poston RD, Buescher CR. The essential role of the clinical research nurse (CRN). Urol Nurs. 2010;30(1):55.

Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(12):1143–56.

Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, Griffith L, Wu P, Wilson K, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(2):141–8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70576-9.

Speicher LA, Fromell G, Avery S, Brassil D, Carlson L, Stevens E, et al. The critical need for academic health centers to assess the training, support, and career development requirements of clinical research coordinators: recommendations from the clinical and translational science award research coordinator taskforce. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5(6):470–5.

Morgan SE, Mouton A, Occa A, Potter J. Clinical trial and research study recruiters’ verbal communication behaviors. J Health Commun. 2016:1–8.

Moskowitz GB, Okten IO, Gooch CM. On race and time. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(11):1783–94.

Moskowitz GB, Stone J, Childs A. Implicit stereotyping and medical decisions: unconscious stereotype activation in practitioners’ thoughts about African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):996–1001.

Bean MG, Stone J, Badger TA, Focella ES, Moskowitz GB. Evidence of nonconscious stereotyping of Hispanic patients by nursing and medical students. Nurs Res. 2013;62(5):362.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2000;320(7227):114–6. doi:10.2307/25186804.

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. The qualitative researcher’s companion. 2002:305-29.

Heifetz RA, Laurie DL. The work of leadership. Harv Bus Rev. 1997;75:124–34.

Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and US health care. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7–14.

Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):358.

Jones JH. Bad blood. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1993.

Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, et al. Cultural competency: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356.

Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J, Services TFoCP. Culturally competent healthcare systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3):68–79.

Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Hays JC, Olsen M, Arnold R, Christakis NA, et al. Identifying, recruiting, and retaining seriously-ill patients and their caregivers in longitudinal research. Palliat Med. 2006;20(8):745–54. doi:10.1177/0269216306073112.

Sonstein SA, Seltzer J, Li R, Silva H, Jones CT, Daemen E. Moving from compliance to competency: a harmonized core competency framework for the clinical research professional. Clin Res. 2014;28(3):17–23.

Snyder DC, Brouwer RN, Ennis CL, Spangler LL, Ainsworth TL, Budinger S, et al. Retooling institutional support infrastructure for clinical research. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;48:139–45.

Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease: a study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(2):166–72.

National Institutes of Health. Clear communication: an NIH health literacy initiative. 2012. https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication.

Malat J, Clark-Hitt R, Burgess DJ, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Van Ryn M. White doctors and nurses on racial inequality in health care in the USA: whiteness and colour-blind racial ideology. Ethn Racial Stud. 2010;33(8):1431–50.

Hall S. The spectacle of the other. Discourse theory and practice: a reader. 2001;1:324–44.

Olson DP, Windish DM. Communication discrepancies between physicians and hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1302–7.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):175–84.

Safeer RS, Keenan J. Health literacy: the gap between physicians and patients. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(3):463–8.

Krieger JL, Parrott RL, Nussbaum JF. Metaphor use and health literacy: a pilot study of strategies to explain randomization in cancer clinical trials. J Health Commun. 2010;16(1):3–16.

Internal Revenue Service. Internal Revenue Bulletin: 2011–30 2012. http://www.irs.gov/irb/2011-30_IRB/ar08.html. Accessed February 20 2015.

State of Rhode Island. Health equity. 2016. http://www.health.ri.gov/equity/. Accessed December 12 2016.

Bay Areas Regional Health Inequities Initiative. Health equity and community engagement report: best practices, challenges and recommendations for local health departments. 2013. http://barhii.org/download/publications/hecer_regionalsummary.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016.

Featherstone K, Donovan JL. “Why don’t they just tell me straight, why allocate it?” The struggle to make sense of participating in a randomised controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(5):709–19.

Ford ME, Siminoff LA, Pickelsimer E, Mainous AG, Smith DW, Diaz VA et al. Unequal burden of disease, unequal participation in clinical trials: solutions from African American and Latino community members. Health & Social Work. 2013:hlt001.

Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(23):1747–59.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Heather Carman Kuczynski, MPH, CHES for focus group facilitation; Noa Appleton, MPH for review of manuscript and technical assistance; and the participants of the 2013 and 2014 ISC focus groups. This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) (U24#MD006961, PI: Bernadette Boden-Albala).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The New York University’s Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects (UCAIHS) approved the study.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) (U24#MD006961, PI: Bernadette Boden-Albala).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haley, S.J., Southwick, L.E., Parikh, N.S. et al. Barriers and Strategies for Recruitment of Racial and Ethnic Minorities: Perspectives from Neurological Clinical Research Coordinators. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4, 1225–1236 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0332-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0332-y