Abstract

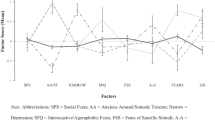

Several lines of research suggest there is considerable overlap between anxiety and depression and that it is difficult to distinguish between these two constructs. However, a few studies utilizing factor analytic procedures have provided evidence that anxiety and depression can be differentiated when measures of these constructs are considered at the item level. In addition, there is some evidence that differentiation can be accomplished in samples experiencing high levels of anxiety (i.e., a clinically anxious sample; B. J. Cox, R. P. Swinson, L. Kuch, & J. Reichman, 1993). In the present study, this research strategy was extended to a sample of patients with high levels of depressed mood (i.e., a mood disorders sample; N = 378). Their responses to widely used measures of depression (i.e., Beck Depression Inventory; A. T. Beck, C. H. Ward, M. Mendelson, J. Mock, & J. Erbaugh, 1961) and anxiety (i.e., Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—State subscale; C. D. Spielberger, R. L. Gorsuch, & R. E. Lushene, 1970) were entered into a principal-components analysis with oblique rotation. A 4-factor solution was retained. This solution was comprised of factors representing anxiety, anxiety absent (a reverse scored factor), cognitive symptoms of depression, and somatic/vegetative symptoms of depression. These findings indicated that anxiety and depression, as emotional states, can be differentiated within a mood disorders sample, using existing popular self-report measures. The clinical and research implications of these findings are briefly discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorderss (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Beck, A. T., Brown, G., Epstein, N., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571.

Bentler, P.M. (1988). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 316–336.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4, 5–13.

Cox, B. J., Cohen, E., Direnfeld, D. M., & Swinson, R. P. (1996). Does the Beck Anxiety Inventory measure anything beyond panic attack symptoms? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 949–954.

Cox, B. J., Swinson, R. P., Kuch, L., & Reichman, J. (1993). Self-report differentiation of anxiety and depression in an anxiety disorders sample. Psychological Assessment, 5, 484–486.

Dobson, K. S. (1985). The relationship between anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 5, 307–324.

Endler, N. S., Cox, B. J., Parker, J. D. A., & Bagby, R. M. (1992). Self-reports of depression and state-trait anxiety: Evidence for differential assessment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 832–838.

Endler, N. S., Edwards, J. M., & Vitelli, R. (1991). Endler Multidimensional Anxiety Scales (manual). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Fan, X., & Wang, L. (1998). Effects of potential confounding factors on fit indices and parameter estimates for true and misspecified SEM models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58, 701–735.

Gotlib, I. H. (1984). Depression and general psychopathology in university students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 19–30.

Haslam, N., & Beck, A. T. (1994). Subtyping major depression: A taxometric analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 686–692.

Hewitt, P. L., & Norton, G. R. (1993). The Beck Anxiety Inventory: A psychometric analysis. Psychological Assessment, 5, 408–412.

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factor in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179–185.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1986). LISREL V I: Analysis of linear structural relationships by maximum likelihood, instrumental variables, and least squares methods. Mooresville, IN: Scientific Software.

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151.

Longman, R. S., Cota, A. A., Holden, R. R., & Fekken, G. C. (1989). A regression equation for the parallel analysis criterion in principal components analysis: Mean and 95th percentile eigenvalues. Multivariate Behaviour Research, 24, 59–69.

Maser, J. D., & Cloninger, C.R. (1990). Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorderss. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Nelson, D. V., & Novy, D. M. (1997). Self-report differentiation of anxiety and depression in chronic pain. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69, 392–407.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics (3rd ed.). New York: Harper Collins.

Watson, D., & Kendall, P. C. (1988). Understanding anxiety and depression: Their relation to negative and positive affective states. In P. C. Kendall & D. Watson (Eds.), Anxiety and depression: Distinctive and overlapping features (pp. 3–26). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Zwick, W. R., & Velicer, W. F. (1986). Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 432–442.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McWilliams, L.A., Cox, B.J. & Enns, M.W. Self-Report Differentiation of Anxiety and Depression in a Mood Disorders Sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 23, 125–131 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010919909919

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010919909919