Abstract

Background:

This randomised phase II trial compared gemcitabine alone vs gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer.

Methods:

Patients were randomly assigned to 4-week treatment with gemcitabine alone (1000, mg m−2 gemcitabine by 30-min infusion on days 1, 8, and 15) or gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy (1000, mg m−2 gemcitabine by 30-min infusion on days 1 and 15 and 40 mg m−2 S-1 orally twice daily on days 1–15). The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS).

Results:

Between July 2006 and February 2009, 106 patients were enrolled. The PFS in gemcitabine and S-1 combination arm was significantly longer than in gemcitabine arm (5.4 vs 3.6 months), with a hazard ratio of 0.64 (P=0.036). Overall survival (OS) for gemcitabine and S-1 combination was longer than that for gemcitabine monotherapy (13.5 vs 8.8 months), with a hazard ratio of 0.72 (P=0.104). Overall, grade 3 or 4 adverse events were similar in both arms.

Conclusion:

Gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy demonstrated longer PFS in advanced pancreatic cancer. Improved OS duration of 4.7 months was found for gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy, though this was not statistically significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Despite extensive research, the prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer remains poor. Because gemcitabine is superior to bolus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), with a response rate of 5% and a median overall survival (OS) of 5.7 months (Burris et al, 1997), combination therapy with gemcitabine and cytotoxic drugs or molecular-targeted agents has been intensely investigated. Only erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine showed a statistically significant but clinically small improvement in OS (Moore et al, 2007), but most phase III clinical trials have failed to demonstrate significant differences in OS. Recently, the efficacy of multiagent regimens was reported in two randomised controlled trials (Reni et al, 2005; Conroy et al, 2011); however, multiagent regimens have potentially increased adverse effects.

S-1 is an oral fluoropyrimidine consisting of tegafur, a prodrug of 5-FU, and two biochemical modulators, 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine and potassium oxonate, with single-agent activity in advanced pancreatic cancer and an objective response rate (ORR) comparable to that for gemcitabine monotherapy (Ueno et al, 2005b; Okusaka et al, 2008). Combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine and S-1 is reportedly well tolerated and active against advanced pancreatic cancer (Nakamura et al, 2005, 2006; Ueno et al, 2005a; Kim et al, 2009; Lee et al, 2009; Oh et al, 2010). Initially, combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine and S-1 was reported as a 3-week regimen, but our modified 4-week regimen demonstrated a time to progression of 10.0 months and OS of 20.4 months with mild adverse effects in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (Nakai et al, 2009).

Here, we conducted a multicentre, randomised phase II trial of gemcitabine alone vs combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Patients and methods

Trial design

This multicentre, open-label randomised phase II trial was conducted at six centres in Japan. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each centre. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study, which was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000000498), was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The primary trial end point was progression-free survival (PFS). The secondary end points were OS, ORR, and safety.

Eligibility

The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) pancreatic adenocarcinoma diagnosed by pathological examination or typical radiographic findings; (2) unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease; (3) no prior treatment for pancreatic cancer including surgery or radiation therapy; (4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2; (5) age >20 years; (6) capability of oral intake; (7) life expectancy >12 weeks; and (8) adequate organ function, as indicated by a white blood cell count >3000 per mm3, platelet count >100 000 per mm3, haemoglobin >10.0 g dl−1, serum creatinine <1.5 times the normal upper limit, creatine clearance >50 ml per min, total bilirubin <2 times the normal upper limit, and aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels <5 times the normal upper limit. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) severe complications, such as active infection, cardiac or renal disease, marked pleural effusion, or ascites; (2) active gastrointestinal bleeding; (3) severe drug hypersensitivity; (4) active concomitant malignancy; and (5) pregnancy or lactation.

Randomisation

Patients were randomly assigned to each treatment arm on a 1 : 1 basis according to a computer-generated minimisation method, stratified by enrolling centre and extent of disease (locally advanced vs metastatic).

Treatment

Patients randomly allocated to the gemcitabine arm received gemcitabine intravenously at 1000, mg m−2 over 30 min on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 4-week cycle. Patients randomly allocated to the gemcitabine and S-1 arm received gemcitabine intravenously at 1000, mg m−2 over 30 min on days 1 and 15 and S-1 orally twice daily for 2 weeks followed by a 2-week rest between each 4-week cycle. Three doses of S-1 were established according to the body surface area (BSA) as follows: BSA ⩽1.25 m2, 80 mg per day; 1.25 m2

Assessments

Tumour responses were measured by computed tomography, which was performed at baseline, and then every two cycles (8 weeks); tumour responses were evaluated using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) 1.0 (Therasse et al, 2000). CA19-9 levels were measured at baseline and at each cycle.

Adverse events and dose modification

All adverse events were evaluated at each cycle according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 3.0 (see http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html). Treatment was temporarily suspended in the case of grade 3/4 haematological toxicity or grade 2 or higher non-haematological toxicity. After recovery to grade 1 toxicity or lower, treatment was restarted at the following reduced doses. In the gemcitabine arm, gemcitabine was reduced by 200 mg m−2. In the gemcitabine and S-1 arm, S-1 was reduced to: BSA ⩽1.25 m2, 50 mg per day; 1.25 m2

Statistics

The primary end point hypothesis used for sample-size estimation was that combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 would increase the median PFS by 2 months (from 3 to 5 months) compared with gemcitabine monotherapy with a type I error probability of 5% (one-sided) and power of 80%. The required number of patients was 50 and a 5% dropout was accounted for in the sample-size calculation. The OS from randomisation was calculated from the date of randomisation to the date of death from any cause or censored at the last follow-up. The PFS was calculated from the date of randomisation to the date of either disease progression or death or censored at the last follow-up. The OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and were compared between treatment arms using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratios with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The ORRs were reported as best achieved response rates. Proportions between the arms were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s test; quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon test. All analyses were conducted based on the intention-to-treat principle. Two-sided P-values <0.05 were considered to be significant. The final analysis was based on follow-up information, which was collected until February 2011. JMP 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Patients

A total of 106 patients were randomly assigned in six hospitals in Japan between July 2006 and February 2009. The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two arms. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. One patient in the gemcitabine arm and two patients in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm received no study drug. All 106 patients were assessable for OS, PFS, and response; 103 patients were assessable for safety.

At the time of analysis, six patients (two in the gemcitabine arm and four in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm) were still alive. The total number of cycles was 277 and 328 in the gemcitabine and gemcitabine plus S-1 arms, respectively. The median follow-up period was 10.0 months.

Efficacy

The ORR according to RECIST 1.0 (Table 2) was 18.9% (95% CI: 10.6–31.4%) in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm, compared with 9.4% (95% CI: 4.9–20.3%) in the gemcitabine arm (P=0.265). Only one patient in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm had a complete response. The median response duration was 10.0 months in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm and 10.6 months in the gemcitabine arm. The disease control rate of 79.2% in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm was significantly higher than that (56.6%) in the gemcitabine arm (P=0.021). Table 2 summarises our efficacy results.

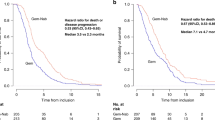

The median PFS (Figure 2) for combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 was 5.4 months (95% CI: 3.7–9.4 months) while that for gemcitabine monotherapy was 3.6 months (95% CI: 2.0–5.1 months). Combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 demonstrated a significantly improved PFS over gemcitabine monotherapy, with a hazard ratio of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.42–0.97; P=0.036).

The median OS was 13.5 months (95% CI: 7.8–16.3 months) in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm and 8.8 months (95% CI: 7.0–10.6 months) in the gemcitabine arm (Figure 3). The 1-year survival rate was 52.8% in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm and 30.2% in the gemcitabine arm (P=0.031). The improvement in OS did not reach statistical significance, with a hazard ratio of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.48–1.07; P=0.104).

Median PFS and OS in locally advanced disease are 12.6 vs 8.1 months and 23.9 vs 11.0 months in gemcitabine and S-1 arm vs gemcitabine arm, respectively. Meanwhile, median PFS and OS in metastatic disease are similar (4.0 vs 2.4 months) and (8.9 vs 7.9 months), respectively (Table 2).

Post hoc subgroup analysis with a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score of 100 showed that combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 demonstrated a longer OS of 15.0 months (95% CI: 8.9–23.9 months), compared with 8.5 months (95% CI: 7.0–11.0 months) for gemcitabine monotherapy (P=0.011). Meanwhile, in patients with a KPS <100, no significant difference was found in OS of 6.8 months (95% CI: 3.7–15.4 months) in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm and 8.8 months (95% CI: 5.0–11.3 months) in the gemcitabine arm (P=0.997).

Eight patients without pathological diagnosis were included in our study. There were no differences in OS between patients with and without pathological diagnosis (10.0 vs 10.1 months, P=0.982). When patients with pathological diagnosis were analysed, PFS was 5.4 vs 2.9 months (P=0.011) and OS was 15.0 vs 8.2 months (P=0.022) in gemcitabine and S-1 arm vs gemcitabine arm.

The treatment after study drug failure was selected at the discretion of the individual investigator. No patients with locally advanced disease received chemoradiation therapy after study drug failure. Second-line chemotherapy was administered to 31 patients (58.5%) in the gemcitabine arm and 18 (34.0%) in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm, respectively (P=0.019). Notably, S-1 was administered alone or as combination therapy in all 31 gemcitabine-failure patients receiving second-line chemotherapy. Overall survival after the introduction of second-line chemotherapy was 5.0 and 5.3 months in the gemcitabine and gemcitabine plus S-1 arms, respectively (P=0.296). The regimens of chemotherapy after study drug failure are shown in Figure 4. The number of administered drugs during the clinical course was ⩾2 in 58.5% vs 96.2%, ⩾3 in 15.1% vs 34.0%, and 4 in 3.8% vs 9.4% in the gemcitabine and gemcitabine plus S-1 arms, respectively.

Safety and dose intensity

Treatment-related adverse events are shown in Table 3. The overall number of grade 3 or greater toxicities did not increase in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm (53.8% in the gemcitabine arm and 43.1% in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm). Neutropenia was the most frequent grade 3 or greater toxicity in both arms. Non-haematological grade 3 or greater toxicities were infrequent in both groups, but stomatitis, diarrhoea and rash were more often seen in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm. No chemotherapy-related death occurred.

The mean dose intensity for gemcitabine was 618.2 mg m−2 per week (82.4% of the planned dose) in the gemcitabine arm and 489.0 mg m−2 per week (97.8% of the planned dose) in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm. The mean dose intensity for S-1 was 251.4 mg m−2 per week (89.8% of the planned dose) in the gemcitabine and S-1 arm.

Discussion

In the present randomised phase II trial, combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 demonstrated a longer median PFS and higher 1-year survival rate with similar severe adverse effects compared with gemcitabine monotherapy. The addition of S-1 to gemcitabine led to a 4.7-month improvement in the median OS; however, this result was not statistically significant.

Combination therapy with gemcitabine and other cytotoxic drugs or molecular-targeted agents has been thoroughly investigated in patients with pancreatic cancer, but no significant improvement in OS has been confirmed in a single, randomised controlled trial, except for combination therapy with gemcitabine and erlotinib (Moore et al, 2007). However, the improvement in OS was modest with a median survival of 6.24 months for combination therapy with gemcitabine and erlotinib vs 5.91 months for gemcitabine monotherapy. In a meta-analysis, capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine similar to S-1, in combination with gemcitabine, was shown to improve OS compared with gemcitabine alone with a hazard ratio of 0.86 (Cunningham et al, 2009). Recently, Conroy et al (2011) reported a significantly longer OS with FORFIRINOX than gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Thus, fluoropyrimidine is currently a key drug in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer. In adjuvant settings (Neoptolemos et al, 2010), the OS with 5-FU plus folinic acid was as effective as gemcitabine. S-1 is also an oral fluoropyrimidine that has been reported to be active against pancreatic cancer. We previously reported promising data for combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 using a 4-week schedule (Nakai et al, 2009). This subsequent randomised controlled trial demonstrated a significantly longer PFS (the primary end point) and higher 1-year survival rate. Despite an improvement in OS of 4.7 months with a hazard ratio of 0.72 for combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1, this difference did not reach statistical significance. In a post hoc analysis of patients with a KPS of 100, the median OS was significantly longer in patients treated with gemcitabine and S-1 (15.0 vs 8.5 months; P=0.011). The trend toward improved results with combination therapy in patients with a good performance status was also reported for combination therapy with gemcitabine and capecitabine (Herrmann et al, 2007). By contrast, OS with gemcitabine monotherapy showed similar results regardless of the KPS score in our study (8.5 months with KPS=100 vs 8.8 months with KPS <100).

The problem often encountered with randomised controlled trials of combination therapy with gemcitabine and other drugs is the crossover to experimental drugs in the gemcitabine arm. In our study, 31 patients (58.5%) in the gemcitabine monotherapy arm received S-1 as second-line chemotherapy. In Japan, both gemcitabine and S-1 are approved for the treatment of pancreatic cancer and are widely used in clinical practice. Therefore, patients in gemcitabine arm had easy access to S-1 as second-line treatment. Although second-line chemotherapy has not been established in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer, S-1 has been reported to be useful in this setting (Morizane et al, 2009; Sudo et al, 2011). This crossover might obscure the efficacy of combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 over gemcitabine monotherapy. As S1 improved the prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer using a historical cohort design (Nakai et al, 2010a, 2010b), the introduction of new effective drugs could lead to improved survival even in patients with pancreatic cancer refractory to gemcitabine. In addition to gemcitabine and S-1, oxaliplatin (Isayama et al, 2011) and irinotecan were administered to refractory patients in the present study. However, drugs other than gemcitabine and S-1 were not approved for treatment of pancreatic cancer and were administered only as clinical trials. As a result, the introduction rate of second-line treatment was lower in gemcitabine and S-1 arm compared with gemcitabine arm (34.0% vs 58.5%). The rate of patients receiving three or four anticancer drugs was higher in the combination therapy arm. As shown for colorectal cancer (Grothey et al, 2004), the availability of multiple drugs might be associated with prolonged survival in pancreatic cancer. Thus, the development of multiple effective drugs and appropriate combination regimens is as important as randomised controlled trials of first-line chemotherapy.

Given the palliative role of chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, safety is as important as efficacy. Our 4-week regimen of combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 did not significantly increase the overall severe toxicity. This regimen allowed a biweekly hospital visit compared with three times a month for gemcitabine monotherapy, which could also decrease the treatment burden for incurable patients. In this sense, FORFIRINOX (Conroy et al, 2011), the first regimen without gemcitabine that was demonstrated to be superior to gemcitabine, was associated with severe toxicities, including febrile neutropenia.

Some limitations to our study exist. First, the sample size (106 patients) was relatively small. Although combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 achieved the primary end point of PFS and improved the median OS duration by 4.7 months, this difference in OS did not reach statistical significance. At the Annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2011, two other randomised controlled trials of gemcitabine alone vs gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy were reported (Ioka et al, 2011; Omuro et al, 2011). While one phase II trial (Omuro et al, 2011) demonstrated significant superiority of combination arm in ORR, time-to-progression and OS, the other large phase III trial (Ioka et al, 2011) showed significantly longer PFS, but failed to demonstrate superiority in OS. The results might differ because the schedule and planned dose intensity were somewhat different in these three trials. Given the failure of one phase III trial, another large scale phase III trial is necessary to confirm the survival benefit of this combination therapy but we should select patients who are most likely to benefit from combination therapy, that is, better PS. In addition, the best dose intensity should be considered in those study population. Second, our 4-week regimen was safely administered to patients with advanced pancreatic cancer without a significant increase in overall severe toxicity compared with gemcitabine monotherapy, but the planned dose intensity was lower than the 3-week regimen used in other studies (Nakamura et al, 2005, 2006; Ueno et al, 2005a). This difference in dose intensity might influence the efficacy of the gemcitabine and S-1 arm, although our 4-week regimen showed high tolerability with a relatively high actual dose intensity.

In conclusion, this randomised trial demonstrated a longer PFS and higher 1-year survival rate for combination therapy with gemcitabine and S-1 in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Overall survival was also significantly longer in patients with a good performance status (KPS=100). Thus, a large-scale, phase III randomised controlled trial is warranted.

Change history

23 January 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD (1997) Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 15 (6): 2403–2413

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardiere C, Bennouna J, Bachet JB, Khemissa-Akouz F, Pere-Verge D, Delbaldo C, Assenat E, Chauffert B, Michel P, Montoto-Grillot C, Ducreux M (2011) FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364 (19): 1817–1825

Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, Valle JW, Smith D, Steward W, Harper PG, Dunn J, Tudur-Smith C, West J, Falk S, Crellin A, Adab F, Thompson J, Leonard P, Ostrowski J, Eatock M, Scheithauer W, Herrmann R, Neoptolemos JP (2009) Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine vs gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 27 (33): 5513–5518

Grothey A, Sargent D, Goldberg RM, Schmoll HJ (2004) Survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer improves with the availability of fluorouracil-leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in the course of treatment. J Clin Oncol 22 (7): 1209–1214

Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schuller J, Saletti P, Bauer J, Figer A, Pestalozzi B, Kohne CH, Mingrone W, Stemmer SM, Tamas K, Kornek GV, Koeberle D, Cina S, Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W (2007) Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 25 (16): 2212–2217

Ioka T, Ikeda M, Ohkawa S, Yanagimoto H, Fukutomi A, Sugimori K, Baba H, Yamao K, Shimamura T, Chen J, Mizumoto K, Furuse J, Funakoshi A, Hatori T, Yamaguchi T, Egawa S, Sato A, Ohashi Y, Cheng A, Okusaka T (2011) Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1 (GS) vs S-1 vs gemcitabine (GEM) in unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer (PC) in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol 29 (15 suppl): 4007

Isayama H, Nakai Y, Yamamoto K, Sasaki T, Mizuno S, Yagioka H, Yashima Y, Kawakubo K, Kogure H, Arizumi T, Togawa O, Ito Y, Matsubara S, Yamamoto N, Sasahira N, Hirano K, Tsujino T, Tada M, Omata M, Koike K (2011) Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy for patients with refractory pancreatic cancer. Oncology 80 (1–2): 97–101

Kim MK, Lee KH, Jang BI, Kim TN, Eun JR, Bae SH, Ryoo HM, Lee SA, Hyun MS (2009) S-1 and gemcitabine as an outpatient-based regimen in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 39 (1): 49–53

Lee GW, Kim HJ, Ju JH, Kim SH, Kim HG, Kim TH, Kim HJ, Jeong CY, Kang JH (2009) Phase II trial of S-1 in combination with gemcitabine for chemo-naive patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 64 (4): 707–713

Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Murawa P, Walde D, Wolff RA, Campos D, Lim R, Ding K, Clark G, Voskoglou-Nomikos T, Ptasynski M, Parulekar W (2007) Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 25 (15): 1960–1966

Morizane C, Okusaka T, Furuse J, Ishii H, Ueno H, Ikeda M, Nakachi K, Najima M, Ogura T, Suzuki E (2009) A phase II study of S-1 in gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 63 (2): 313–319

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, Ito Y, Kogure H, Togawa O, Matsubara S, Arizumi T, Yagioka H, Yashima Y, Kawakubo K, Mizuno S, Yamamoto K, Hirano K, Tsujino T, Ijichi H, Tateishi K, Toda N, Tada M, Omata M, Koike K (2010a) Impact of S-1 on the survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 39 (7): 989–993

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, Ito Y, Kogure H, Togawa O, Matsubara S, Arizumi T, Yagioka H, Yashima Y, Kawakubo K, Mizuno S, Yamamoto K, Hirano K, Tsujino T, Ijichi H, Toda N, Tada M, Kawabe T, Omata M (2009) A pilot study for combination chemotherapy using gemcitabine and S-1 for advanced pancreatic cancer. Oncology 77 (5): 300–303

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, Kogure H, Hirano K, Tsujino T, Ijichi H, Tateishi K, Tada M, Omata M, Koike K (2010b) Impact of S-1 in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 40 (8): 774–780

Nakamura K, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Kobayashi A, Tadenuma H, Sudo K, Kato H, Saisho H (2005) Phase I trial of oral S-1 combined with gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 92 (12): 2134–2139

Nakamura K, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Sudo K, Kato H, Saisho H (2006) Phase II trial of oral S-1 combined with gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 94 (11): 1575–1579

Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, Padbury R, Moore MJ, Gallinger S, Mariette C, Wente MN, Izbicki JR, Friess H, Lerch MM, Dervenis C, Olah A, Butturini G, Doi R, Lind PA, Smith D, Valle JW, Palmer DH, Buckels JA, Thompson J, McKay CJ, Rawcliffe CL, Buchler MW (2010) Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 304 (10): 1073–1081

Oh DY, Cha Y, Choi IS, Yoon SY, Choi IK, Kim JH, Oh SC, Kim CD, Kim JS, Bang YJ, Kim YH (2010) A multicenter phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1 combination chemotherapy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 65 (3): 527–536

Okusaka T, Funakoshi A, Furuse J, Boku N, Yamao K, Ohkawa S, Saito H (2008) A late phase II study of S-1 for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 61 (4): 615–621

Omuro Y, Ikari T, Ishii H, Ozaka M, Suyama M, Matsumura Y, Itoi T, Egawa N, Yano S, Hanada K, Kimura Y, Ukita T, Ishida Y, Tani M, Ohoka S, Hirose Y, Hijioka S, Watanabe R, Ikeda T, Nakajima T, Organization JCCR (2011) A randomized phase II study of gemcitabine plus S-1 vs gemcitabine alone in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 29 (15 suppl): 4029

Reni M, Cordio S, Milandri C, Passoni P, Bonetto E, Oliani C, Luppi G, Nicoletti R, Galli L, Bordonaro R, Passardi A, Zerbi A, Balzano G, Aldrighetti L, Staudacher C, Villa E, Di Carlo V (2005) Gemcitabine vs cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 6 (6): 369–376

Sudo K, Yamaguchi T, Nakamura K, Denda T, Hara T, Ishihara T, Yokosuka O (2011) Phase II study of S-1 in patients with gemcitabine-resistant advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 67 (2): 249–254

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92 (3): 205–216

Ueno H, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Ishiguro Y, Morizane C, Matsubara J, Furuse J, Ishii H, Nagase M, Nakachi K (2005a) A phase I study of combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oral S-1 for advanced pancreatic cancer. Oncology 69 (5): 421–427

Ueno H, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Takezako Y, Morizane C (2005b) An early phase II study of S-1 in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncology 68 (2–3): 171–178

Acknowledgements

We thank the participating patients and their families, as well as the additional investigators, study coordinators (Miyuki Tsuchida, Makiko Otake at Clinical Research Support Center, The University of Tokyo Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Nakai, Y., Isayama, H., Sasaki, T. et al. A multicentre randomised phase II trial of gemcitabine alone vs gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer: GEMSAP study. Br J Cancer 106, 1934–1939 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.183

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.183