Abstract

Background:

Around 1 in 10 of all cancer cases occur in adults of reproductive age. Cancer and its treatments can cause long-term effects, such as loss of fertility, which can lead to poor emotional adjustment. Unmet information needs are associated with higher levels of anxiety. US research suggests that many oncologists do not discuss fertility. Very little research exists about fertility information provision in the United Kingdom. This study aimed to explore current knowledge, practice and attitudes among oncologists in the United Kingdom regarding fertility preservation in patients of child-bearing age.

Methods:

A national online survey of 100 oncologists conducted online via medeconnect, a company which has exclusive access to the doctors.net.uk membership of GMC registered doctors.

Results:

Oncologists saw fertility preservation (FP) as mainly a women’s issue, and yet only felt knowledgeable about sperm storage, not other methods of FP; 87% expressed a need for more information. Most reported discussing the impact of treatment on fertility with patients, but only 38% reported routinely providing patients with written information, and 1/3 reported they did not usually refer patients who had questions about fertility to a specialist fertility service. Twenty-three per cent had never consulted any FP guidelines. The main barriers to initiating discussions about FP were lack of time, lack of knowledge, perceived poor success rates of FP options, poor patient prognosis and, to a lesser extent, if the patient already had children, was single, or could not afford FP treatment.

Conclusion:

The findings from this study suggest a deficiency in UK oncologist’s knowledge about FP options and highlights that the provision of information to patients about FP may be sub-optimal. Oncologists may benefit from further education, and further research is required to establish if patients perceive a need for further information about FP options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Around 1 in 10 of all cancer cases occur in adults of reproductive age, between the ages of 25 and 49. The most common cancers in this age group include breast, cervical, testicular and bowel cancers, and also malignant melanoma (Cancer Research UK, 2011). Almost twice as many women as men in this age group are diagnosed with cancer, largely due to the high incidence of breast cancer (Cancer Research UK, 2009, 2011). As detection and treatments improve, patients with cancer live longer, but their lives are impacted by long-term effects of the cancer itself and treatments received (Goldhirsch et al, 2009; Jeruss and Woodruff, 2009). Long-term effects can be psychological, economic, social, sexual and biological (Ibbotson, 1994; Royal College of Physicians; Partridge et al, 2008; Hickey et al, 2009). Loss of fertility is one such long-term effect (Ganz et al, 2003).

Rates of cancer-related infertility in men and women depend on a number of factors including the cancer itself, age, sex, diagnosis and treatment dose (Duffy and Allen, 2009; Hickey et al, 2009; Ajala et al, 2010). For women, treatment may lead to the loss of reproductive organs, premature ovarian failure or an inability to produce mature eggs for ovulation. It is difficult to reliably predict ovarian reserve (Duffy and Allen, 2009), and there are no reliable incidence figures for infertility following cancer treatment in the United Kingdom. Estimates range from 40–70% (Anderson and Wallace, 2008; Partridge et al, 2008; Ajala et al, 2010). For men, malignant disease can influence gonadal function, or cancer treatments may lead to anatomic problems (for example, retrograde ejaculation), hormonal insufficiency, damage or depletion of the germinal stem cells (temporary or permanent), or azoospermia (absence of sperm in the ejaculate) (Dohle, 2010). Figures vary dramatically depending on the treatments received, from 90% of patients experiencing azoospermia, to none (Dohle, 2010). However, new advances in reproductive technologies have meant that methods of fertility preservation (FP) are now available. For men, this is easier than for women - sperm cryopreservation (‘freezing’) is an established technique with a reasonable chance of viable gametes after thawing (Lee et al, 2006). Women can opt for embryo, oocyte, or ovarian tissue cryopreservation, but the latter two until recently were considered experimental techniques (The Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, 2012), and are not yet widely available in the United Kingdom. For women, FP methods may in some cases require a delay in the start of cancer treatment and invasive procedures including hormonal stimulation, which might not be advisable in some situations (Quinn et al, 2009).

Loss of fertility can be devastating for younger adults. The emotional impact can be severe and long-lasting (Dow, 1994; Mor et al, 1994; Cimprich et al, 2002; Ganz et al, 2003; Bloom et al, 2004; Partridge et al, 2004). Furthermore it has been shown that women who do not have a discussion with a health care professional about fertility and who have unmet information needs tend to have higher levels of anxiety (Braun et al, 2005; Griggs et al, 2007).

Many cancer patients are interested in FP, and would prefer a biological child to adoption or third-party reproduction (Schover, 1999; Schover et al, 1999; Quinn et al, 2009). Timely information about FP early on in the oncology pathway, as soon as possible after diagnosis, has been recognised as of major importance to satisfactory outcomes for this patient group (Braun et al, 2005), and guidelines have been issued to oncologists.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology published guidance in 2006, recommending that oncologists should address the possibility of infertility with patients before their cancer treatment at the earliest possible opportunity, be prepared to discuss possible FP options, and refer patients to reproductive specialists (Lee et al, 2006). They also stated that sperm and embryo cryopreservation were widely available and considered standard practice, and that other methods were experimental but could be performed in centres with the necessary expertise (Lee et al, 2006).

Similarly, a UK working party (formed by members of the Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Radiologists, and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) published extensive guidance in 2007 including information on the effect of cancer treatments on fertility, recommended procedures and management. It recommends that patients should be fully informed about the risk of infertility before gonadotoxic treatment and have discussions about alternative treatment strategies if relevant; patients should be given written information and have access to specialist psychological support and counselling; sperm banking ought to be considered for all males undergoing treatment that carries a risk of long-term gonadal damage, and all females should be fully informed about possibility of early menopause and infertility, and be offered embryo storage if possible (Royal College of Physicians).

However, the extent to which this guidance is being implemented in practice is unclear. Research from the United States suggests that information given to patients is often perceived as inadequate or untimely (Partridge et al, 2004; Thewes et al, 2005) and that between one-third and two-thirds of patients do not have a discussion with their oncologist regarding the impact of cancer treatment on their fertility (Duffy et al, 2005; Duffy and Allen, 2009; Quinn et al, 2009). Uncertainty exists over who should initiate the fertility discussion (Thewes et al, 2005; King et al, 2008). There is some limited research on barriers to fertility discussions, which cites personal values, knowledge of available resources, perceived risks and institutional factors (e.g., referral sites and practice guidelines) as the main barriers or facilitators for these discussions (Goodwin et al, 2007; Quinn et al, 2008; King et al, 2008; Vadaparampil et al, 2008; Forman et al, 2010). Very limited published research is available on the practices and views of oncologists treating adult patients in the United Kingdom. A survey of Irish oncologists of FP for male patients suggested that 73% routinely discussed sperm cryopreservation, but 92% would only refer men between the ages of 20 and 40, and 92% were unaware that sperm cryopreservation did not delay cancer treatment(Allen et al, 2003).

This study aimed to explore current knowledge, practice, and attitudes of FP among oncologists in the United Kingdom.

Materials and methods

Measures

A 35-item survey was developed on the basis of previous research conducted in the United States (Quinn et al, 2009; Forman et al, 2010). Where relevant, the same items were used, sometimes with adaptation for a British context (Quinn et al, 2009; Forman et al, 2010). For a full copy of the questionnaire see Appendix 1.

Demographic, medical training and practice information

Demographic questions included physicians’ sex, age, ethnicity, religious affiliation, whether they had children and whether they had personal experience of cancer. Qualifications, specialty and grade of the Oncologist completing the survey, and caseload information were also recorded.

Knowledge of FP

Participants were asked to indicate their knowledge of six different FP options (cryopreservation of ovarian tissue, oocytes, sperm or testicular tissue, in vitro fertilisation with embryo cryopreservation, and pre-treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormones) on a four-point Likert scale from ‘not at all knowledgeable’ to ‘very knowledgeable’. They were also asked about the frequency with which they encountered patients who had used any of these methods (from ‘never’ to ‘often’) and if they felt they needed more information about FP.

Current practice behaviours

Practice behaviours were evaluated using six statements (e.g., ‘I check with the patient how important their future fertility is for them’). Oncologists indicated agreement with the statements on a four-point Likert scale (never to always). Additional questions asked whether oncologists provided written information, if yes, the source of that information, if guidelines were consulted, and if patients were referred to fertility specialists.

Barriers to FP

Seventeen items were used to assess barriers to FP experienced by oncologists. Three items assessed structural aspects, that is, if FP was available in the local NHS trust, proximity to the nearest reproductive medicine unit and professional links with that unit. Fourteen questions ascertained which factors oncologists thought might have a role, both in terms of characteristics of their practice or FP per se (six items, e.g., ‘Lack of fertility services in the area’) and characteristics of the patient (eight items, e.g., ‘The patient is too ill to delay treatment to pursue FP’). Oncologists were asked to indicate whether any of the items influenced their decision to initiate a discussion about FP on a three-point Likert scale (‘not at all’ to ‘to a large extent’). A free-text box was also provided.

FP attitudes and perceptions

Two items asked what oncologists would consider the upper limit of FP for men and women to be; five items assessed oncologists’ agreement with five-point Likert-scale items (strongly disagree to strongly agree) (e.g., ‘Treating the primary cancer is more important than FP’); oncologists were also asked to indicate their perception of the importance their patients attached to their future fertility in relation to sex, socio-economic status, educational level and cultural background (e.g., ‘Do you think women or men are more concerned about preserving fertility?’). Answer options for the question on cultural background were open—a text box was provided.

A final free-text box was also added to allow oncologists to add any other comments regarding FP.

Procedures

The survey questions were piloted with a small group of oncologists (personal contacts of the authors) to test content, ease of understanding and acceptability. The final questionnaire was distributed electronically via MedeConnect, a UK company specialising in high quality online research with medical professionals, which has exclusive access to the doctors.net.uk membership of GMC registered doctors, which totals 175 000+. They have access to ∼500 oncologists in the United Kingdom. The benefits of using this company include guaranteed access to a number of oncologists (a hard-to-reach group for research), fast turnaround and quick results, and therefore good value for money. According to the latest census, 495 medical oncologists worked in the United Kingdom in 2008. Estimating a similar number of clinical oncologists, we aimed to recruit 100 oncologists, or ∼10% of the workforce, which provides a good and reliable estimate of current practice in the United Kingdom. We selected 100 as a number that we believed would allow us to gain preliminary data from a spectrum of oncologists (in terms of regional location, site specialisation, gender, ethnicity, age and so on). We hoped that this would allow us to obtain sufficient initial data to explore aspects of the knowledge, attitudes and practices of oncologists regarding FP and identify any issues worthy of further research or need for education. Doctors were invited to participate via an e-mail, which contained a link to the survey. The company’s website also contained a link. Oncologists were eligible if they were currently practising in the United Kingdom and were at least a Specialist Registrar grade. Sampling continued until our quota (100 oncologists meeting eligibility criteria) was reached. Participants were given 1000 electronic surfing reward points (eSR points—an electronic reward system, which can be exchanged for online merchandise) as an incentive.

Statistical analysis

Primary analysis was descriptive. Frequencies and proportions were summarised for demographic characteristics and each questionnaire item. Independent sample t-tests were used to explore differences in means, and χ2-tests of independence were used to assess relationships between categorical variables. In cases where distributions of answers was very unequal, some items were turned into dichotomous items, for example, the answer options ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘usually’ and ‘always’ were collapsed into two categories by merging ‘never’ and ‘rarely’ and ‘usually’ and ‘always’.

Analysis of qualitative comments

The text boxes provided in the survey were under-utilised, and did not add substantially to the information provided in the remainder of the survey. The initial plan of analysing qualitative comments using thematic analysis was therefore abandoned.

Results

Participants

The total membership of doctors.net of senior grade oncologists was 1488 at the time of study, of which 560 logged in to the site during the 30-day period of the survey. Three oncologists looked at the survey but did not start it, seven started the main survey but did not complete it, and three were screened out as ineligible.

Characteristics of the oncologists who took part in the survey are detailed in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Knowledge of FP

The only FP method that the majority of oncologists felt knowledgeable or very knowledgeable about was sperm cryopreservation (64%). The methods most participants knew only little about were testicular cryopreservation (86%) and ovarian cryopreservation (82%). In terms of encountering patients who had used any of the options, 75% agreed that they encountered patients who had used sperm cryopreservation sometimes or often, and 38% said this of pre-treatment with GNRH agonists. Eighty-seven per cent of the sample stated they needed more knowledge about FP options.

Current practice behaviours

Most oncologists reported consideration of FP in care provision. For instance, 95% of oncologists reported usually or always checking with their patients how important future fertility was for them, 97% reported discussing with their patients how their condition and/or the treatment may impact on their fertility, and 91% reported taking the patient’s desire for future fertility into account when planning their treatment regimen. However, only 45% of oncologists reported usually or always consulted a fertility specialist or reproductive endocrinologist with questions about fertility issues in their patients, and only 67% reported having referred patients to a fertility specialist.

With regard to information provision, only 38% of oncologists stated that they usually or always provided their patients with written information about FP. If written information was provided, it was most likely either from Macmillan Cancer Support (59%) or the hospital’s own materials (54%). Ten per cent of respondents said that they did not provide any written information about FP to their patients.

Twenty-three per cent of participants stated they had not consulted any guidelines for guidance on fertility issues. Only 43% of respondents have consulted their own hospitals’ guidelines, 32% have consulted the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on fertility treatment and 39% had consulted the guidance published jointly by the Royal Colleges of Physicians (RCP) and Radiographers (RCR) and Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG).

Barriers to FP

The existing infrastructure of fertility services did not seem to be perceived as a major barrier to providing FP by respondents. Seventy per cent of respondents reported FP options were available within their trust; 18% did not know about the availability of fertility services. They also stated that the nearest centre would be either in the same hospital (23%) or the same city (47%) as the treatment centre, and 63% agreed that this was ‘not at all’ a factor in their influence to initiate a fertility discussion with a patient. Similarly, 82% of participants thought their professional links with the nearest reproductive unit were good or very good. In terms of professional factors, 43% stated constraints on their time as having a role to some extent or a large extent, and 63% saw their own lack of knowledge about FP as a determining factor, whereas 81% stated that their perception that FP had poor success rates did to some or a large extent influence whether they initiated a discussion about FP.

The three barriers to discussion of FP most commonly perceived were all related to patients’ clinical characteristics: 93 per cent of oncologists said it would influence their decision to initiate a discussion if the patient was too ill to delay treatment to pursue FP, 88% would be influenced by a patient’s poor prognosis and 72% if the patient had a hormonally sensitive malignancy. Personal factors were less important. Nonetheless, 44% of clinicians said that whether a patient already had children may influence their decision to discuss FP, 21% said that if the patient was lesbian or gay it may influence their decision, 32% said this would be the case if the patient was single, and 27% agreed this to be the case if the patient could not afford FP.

Fertility preservation attitudes and perceptions

The vast majority of oncologists felt the upper age limit they would consider giving FP advice to a women was 45 or under (34% said ‘40’ and 53% said ‘45’). For men, the situation was slightly different, with 60% defining age 55 as the limit and 31% considering no limit. Overall, oncologists seemed supportive of FP, with 59% agreeing or strongly agreeing that FP was a high priority to discuss with newly diagnosed patients, and 65% feeling comfortable to discuss FP. However, 67% also agreed that treating the primary cancer was more important than FP, and 60% strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement that they would be willing to provide a less effective treatment regimen in order to attempt FP. There was also some question over success rates, with 18% agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement that success rates of FP are not as yet good enough to make it a viable option. Finally, oncologists were also asked about the importance of gender, socio-economic status and education in determining the importance of patients attached to preserving their fertility. Eighty-four of oncologists thought that gender of patients had a role, with 70% thinking that women were more concerned than men about preserving their fertility. Seventy-seven per cent also saw the cultural background of their patients as having a role, but when asked to specify which cultural backgrounds, opinions were divergent. Not all respondents answered this question, but of those who did, 22 considered Asian patients to be most concerned. Opinions as to whether socio-economic status and education mattered were also divided, with 48 and 59% thinking they did, respectively.

Bivariate analyses

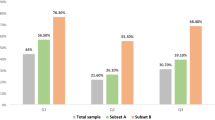

The sample was split by age (40 and under and over 40) and by grade (consultants and all other grades) to examine if seniority and years in service had a bearing on oncologists’ knowledge and attitudes towards FP. Seventy-three per cent of the sample were over age 40, and 48% were Consultants. Independent sample t-tests were employed to examine difference in means. There were no significant differences in knowledge of FP options by either age or grade. A χ2-test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between grade and an information need for FP. The relation between these variables was significant with lower grades stating a higher need for information, χ2 (1, N=100)=11.75, P<0.001.

Independent sample t-tests and χ2-tests were also used to examine the relationship between current practice behaviours and sex, age and grade groups, but no significant differences or relationships were detected (all P-values >0.05). χ2-tests were also used to examine relationships between current practice behaviours and participants’ parity and own experience with cancer. Participants who had children were more likely to provide patients with written information (χ2 (2, N=100)=10.2, P=0.006).

Analysis of variance was used to check for differences in practice behaviours in relation to attitudes to FP. The key question used as a factor was ‘the success rates of FP are not as yet good enough’ as this indicates scepticism towards the issue. However, no significant differences were found (all P-values >0.05) apart from the item about referral (‘I refer patients who have questions about fertility to a fertility specialist or reproductive endocrinologist’), which was approaching significance (P=0.048) but post hoc testing using Gabriel did not show a significant difference between the options (all P-values >0.05).

Discussion

This study reports the findings of a survey of UK oncologists and their knowledge of, and attitudes towards, FP. Our survey describes an overall encouraging picture, with the majority of oncologists being interested in the topic, taking patients’ preferences into account, and referring to specialists where needed. However, knowledge of fertility options could be improved, as could knowledge of and adherence to fertility guidelines, and distribution of information.

Considering the lack of knowledge most oncologists in the sample admitted to, it might be seen as surprising that the majority said they were comfortable discussing FP with patients and that they considered it a priority. However, in-depth knowledge of fertility is not essential in order to discuss the impact of the cancer treatment on fertility, and arguably, it is more important to recognise whether FP is relevant for the particular woman or couple in question, and to know where to refer. Nonetheless, the results alert to a question of what fertility discussions might commonly entail, and what information might be passed on. It would also be interesting to discover how patients experience this information exchange, and further research is needed to detail patients’ perceptions and actual consultations.

Despite the fact that comprehensive cancer-specific fertility information for patients is available (e.g., from charities such as Macmillan Cancer Support), the majority of oncologists did not seem to provide their patients with such information. If any information was given, it was often the hospital’s own. Although this is better than nothing, the quality of the information will vary widely, and might not be standardised, or updated as frequently as that of national charities. This lack of provision is particularly unfortunate as accurate and up-to-date written information on a subject as complex as FP would allow patients to reflect on the issues concerned and help them make a more informed choice (Payne, 2002). The timeframe in which a decision about FP is possible is often very tight, and sits within the tumultuous and emotionally charge time of having received a cancer diagnosis. It is therefore of the utmost importance that this situation is rectified. Helpful in this context are the tumour-site specific information prescriptions and patient information pathways currently developed by the National Cancer Action Team (NCAT)(National Cancer Action Team, 2011).

The vast majority of participants stated that they needed more information about FP. And yet, the main available guidelines were only consulted by a minority. In particular, the RCP, RCOG and RCR working party document (Royal College of Physicians et al, 2007) provides a great deal of information as well as guidance, and would go some way to reducing the information gap. Given that the majority of respondents agreed that treating the primary cancer is more important than preserving fertility, it is hoped that this understandable attitude on the side of the clinician does not prevent patients from accessing information they might need to make their own informed choice.

It is positive also that the existing infrastructure in the United Kingdom was not perceived as a barrier to accessing FP with 70% of respondents saying that FP options were available in their trust. Main perceived barriers to initiating a discussion about FP lay in clinical aspects of individual cases (such as a perception that the patient was too ill to pursue FP), or, perhaps more worryingly, personal aspects of patients, such as their parity or sexual orientation, which may reflect personal attitudes as well as clinical judgment.

To date, there have been few surveys addressing oncologists’ knowledge and attitudes towards FP in adult (non-paediatric) patients. The current survey can be most closely compared with a previous survey of oncologists’ knowledge and practices of treatment-related infertility in female cancer patients by Forman et al, (2010), on the basis of which the questionnaire was developed (Although the questionnaire was also based on a questionnaire developed by Quinn et al, (2009), which the authors kindly shared with us, the results of that study as published cannot easily be compared as they chose to compare demographic and specialty characteristics with physician referral, using multivariate regression, without including frequency data). Forman’s web-survey included 249 respondents in the United States. In terms of initiation of discussion and referral, his survey reports a broadly similar picture to the current study, with 95% of respondents always or usually discussing impact, and with a slightly larger number (82%) ever referring to fertility specialists. Access to facilities seemed also largely similar, which is reassuring given the differences between the US health-care system and the NHS. However, it is worth noting that a high number of respondents of the current survey as well as the US survey came from urban centres where proximity to reproductive medicine units may be less of an issue than in other parts of the country. Nonetheless, less than half of the respondents in the current survey said they consulted a fertility specialist when they had questions about FP in their patients. Given the relative proximity, it may be worth considering utilising these links to a greater effect, and initiating joint training events and greater professional exchange to facilitate better information flow and a more joint-up service for patients.

The main differences between Forman’s respondents and those of the current study lay in the perceived barriers to the initiation of fertility discussions. Interestingly, all of the items, whether of a more clinical or personal nature, were more strongly endorsed by British respondents. For instance, 88% of British respondents said their decision would be influenced by a poor prognosis, compared with 30% of US respondents. Forty-four per cent of UK respondents said that whether a patient already had children may influence their decision to discuss FP, but only 10% of US respondents said it would. Considering equality of access to FP, it is also noteworthy that 21% of respondents to the current study said that if a patient was lesbian or gay might influence their decision, when only 2% of the respondents in Forman et al (2010) survey said that the patient being lesbian may have a bearing on discussion initiation. It may be that the differences are largely due to greater willingness of disclosure overall in the British colleagues. However, some of the issues cited warrant further investigation to ensure that personal attitudes do not hinder equal access to treatment regardless of parity, sexual orientation or other personal characteristics.

Another recent survey of 103 male oncologists’ knowledge and practice of sperm cryopreservation in Saudi Arabia showed striking differences to UK practices as evidenced by this survey. For instance, Rabah et al, (2010) report that 32% of the respondents rarely or never discuss FP with their patients, 39% of said they never referred patients to a fertility specialist, and only half said they were familiar with ICSI (intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection) even though this is considered a routine procedure. Despite these comparatively low discussion and referral figures, 64% considered sperm cryopreservation ‘very important’ and 94% claimed they provided ‘psychological help’ to patients, although it was unclear what this consisted of. These differences are not surprising, given the widely different cultural context in which the surveys took place. Reproduction is an important topic at the intersection of medical science and cultural values, and it is important that more attention is paid to the ways in which reproductive concerns are addressed within medical oncological practice, taking into account local and wider cultural contextual issues.

Limitations

The recruitment procedure for this survey utilised an existing network of electronically active oncologists. This sample may not be representative of the population of oncologists in the United Kingdom. However, the method has the advantage of speed and guaranteed response, which is beneficial considering that previous surveys in the field have suffered from response rates as low as 15% (Forman et al, 2010). However, this method has the disadvantage of not being able to directly calculate the response rate. Oncologists with busy clinics are a difficult to reach group, and this survey was designed as a first step towards establishing baseline figures and to assist in designing further representative surveys and trials.

It is also important to point out that location of participants in terms of tertiary hospitals or District General Hospitals was not available. This work setting may have affected access to resources, for example, availability of hospital-specific patient information. Some confusion over aspects of FP may also have skewed the results in one particular instance: 38% said they had encountered patients who had experienced pre-treatment with GNRH agonists. This is a rather high estimate in the context of other information given in the survey. Given that, GNRH is also used in the treatment of prostate cancer; the authors speculated that some oncologists may be familiar with GNRH antagonists but for reasons other than FP and may have answered this question erroneously.

This highlights a broader issue, namely, that the survey method relies on self-report—which may lead to an over-estimate of current FP practices and which may not be representative of actual behaviour. Nonetheless, it gives an understanding of oncologists’ perceptions, and given that in some instances knowledge of FP and FP-related guidelines was fairly low, still provides a useful indicator for training and information needs. Finally, the survey only provided oncologists’ views, and would be usefully supplemented by views of nursing staff and patients.

Conclusion

Overall the study presents an encouraging picture, with the majority of oncologists being interested in FP, taking patients’ preferences into account and referring to specialists where needed. However, the overall lack of knowledge of methods other than sperm cryopreservation suggests that oncologists may benefit from further education and information about current reproductive medicine procedures available. Information sharing should be improved, utilising the tumour-site specific information prescriptions and patient information pathways currently developed by the National Cancer Action Team (NCAT)(National Cancer Action Team, 2011). An improved understanding of the influence of personal attitudes of clinicians on their clinical judgment (e.g., here about initiating discussions or referral for FP options) is useful in highlighting the potential impact of stereotypes or prejudices, which may prevent equal access to resources. Further research is needed to provide a representative picture of the status quo in the United Kingdom. It would also be helpful to provide more insight into the experiences of patients of interactions with their caregivers over FP.

Change history

30 April 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Ajala T, Rafi J, Larsen-Disney P, Howell R (2010) Fertility preservation for cancer patients: a review. Obstetr Gynaecol Int 2010: 160386 (Article ID 160386, 9 pages).

Allen C, Keane D, Harrison RF (2003) A survey of Irish consultants regarding awareness of sperm freezing and assisted reproduction. Irish Med J 96 (1): 23–25.

Anderson RA, Wallace WH (2008) Uncertainties in preserving fertility in cancer treatment. BMJ 337: a2577.

Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Chang S, Banks PJ (2004) Then and now: quality of life of young breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 13: 147–160.

Braun M, Hasson-Ohayon I, Perry S, Kaufman B, Uziely B (2005) Motivation for giving birth after breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 14 (4): 282–296.

Cancer Research UK (2009) November 2009). Cancer in the UK Retrieved 01 June 2010 from http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/prod_consump/groups/cr_common/@nre/@sta/documents/generalcontent/018070.pdf.

Cancer Research UK (2011) . Cancer incidence by age- UK statistics Retrieved 22 July, 2011, from http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence/age/#Adults.

Cimprich B, Ronis DL, Martinez-Ramos G (2002) Age at diagnosis and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Practice 10 (2): 85–93.

Dohle GR (2010) Male infertility in cancer patients: review of the literature. Int J Urol 17: 327–331.

Dow KH (1994) Having children after breast cancer. Cancer Practice 2 (6): 407–413.

Duffy C, Allen S (2009) Medical and psychosocial aspects of fertility after cancer. Cancer J 15 (1): 27–33.

Duffy C, Allen S, Clark MA (2005) Discussions Regarding Reproductive Health for Young Women With Breast Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 23 (4): 766–773.

Forman EJ, Anders CK, Behera MA (2010) A nationwide survey of oncologists regarding treatment-related infertility and fertility preservation in female cancer patients. Fertility Sterility 94 (5): 1652–1656.

Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE (2003) Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol 21 (22): 4184–4193.

Goldhirsch A, Ingle JN, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Thürlimann B, Senn HJ (2009) Thresholds for therapies: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2009. Ann Oncol 20 (8): 1319–1329.

Goodwin T, Oosterhuis BE, Kiernan M, Hudson MM, Dahl GV (2007) Attitudes and practices of pediatric oncology providers regarding fertility issues. Pediatric Blood Cancer 48: 80–85.

Griggs JJ, Sorbero MES, Mallinger JB, Quinn M, Waterman M, Brooks B, Shields CG (2007) Vitality, mental health, and satisfaction with information after breast cancer. Patient Edu Counsel 66 (1): 58–66.

Hickey M, Peate M, Saunders CM, Friedlander M (2009) Breast cancer in young women and its impact on reproductive function. Human Reproduction Update 15 (3): 323–339.

Ibbotson T (1994) Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the effects of disease and treatment. Eur J Cancer 30A: 37–40.

Jeruss JS, Woodruff TK (2009) Preservation of fertility in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 360 (9): 902–911.

King L, Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, Gwede CK, Miree CA, Wilson C, Perrin K (2008) Oncology nurses' perceptions of barriers to discussion of fertility preservation with patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nursing 12 (3): 467–476.

Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, Patrizio P, Wallace WH, Hagerty K, Oktay K (2006) American society of clinical oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 24 (18): 2917–2931.

Mor V, Malin M, Allen S (1994) Age differences in the psychosocial problems encountered by breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Institute Monographs 16: 191–197.

National Cancer Action Team (2011) Improving Patient Information Retrieved 23 August, 2011, from http://www.ncat.nhs.uk/our-work/improvement/improving-patient-information.

Partridge A, Gelber S, Peppercorn J, Ginsburg E, Sampson E, Rosenberg R, Winer E (2008) Fertility and menopausal outcomes in young breast cancer survivors. Clinical Breast Cancer 8 (1): 65–69.

Partridge A, Gelber S, Peppercorn J, Sampson E, Knudsen K, Laufer M, Winer EP (2004) Web-based survey of fertility issues in young women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 22 (20): 4174–4183.

Payne S (2002) Balancing information needs: dilemmas in producing patient information leaflets. Health Informatics Journal 8: 174–179.

Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, Bell-Ellison BA, Gwede CK, Albrecht TL (2008) Patient-physician communication barriers regarding fertility preservation among newly diagnosed cancer patients. Social Science Med 66: 784–789.

Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, Gwede CK, Miree CA, King L, Clayton H, Munster P (2007) Discussion of fertility preservation with newly diagnosed patients: oncologists’ views. J Cancer Survivorship 1: 146–155.

Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, King L, Miree CA, Wilson C, Raj O, Albrecht TL (2009) Impact of physicians' personal discomfort and patient prognosis on discussion of fertility preservation with young cancer patients. Patient Edu Counsel 77: 338–343.

Quinn G, Vadaparampil ST, Lee J-H, Jacobsen PB, Bepler G, Lancaster J, Albrecht TL (2009) Physician referral for fertility preservation in oncology patients: a National Study of Practice Behaviors. J Clin Oncol 27 (35): 5952–5957.

Rabah D, Wahdan I, Merdawy A, Abourafe B, Arafa M (2010) Oncologists’ knowledge and practice towards sperm cryopreservation in Arabic communities. J Cancer Survivorship 4 (3): 279–283.

Royal College of Physicians, The Royal College of Radiologists, and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2007) The effects of cancer treatment on reproductive functions: Guidance on management. Report of a Working Party. Royal College of Physicians: London, UK.

Schover LR (1999) Psychosocial aspects of infertility and decisions about reproduction in young cancer survivors: a review. Med Pediatric Oncol 33: 53–59.

Schover LR, Rybicki LA, Martin BA, Bringelsen KA (1999) Having children after cancer: a pilot survey of survivors' attitudes and experiences. Cancer 86 (4): 697–709.

The Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (2012) Mature oocyte cryopreservation: a guideline. Fertility Sterility 99 (1): 37–43.

Thewes B, Meiser B, Taylor A, Phillips KA, Pendlebury S, Capp A, Friedlander M (2005) Fertility- and Menopause-Related Information Needs of Younger Women With a Diagnosis of Early Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 23 (22): 5155–5165.

Vadaparampil S, Quinn G, King L, Wilson C, Nieder M (2008) Barriers to fertility preservation among pediatric oncologists. Patient Edu Counsel 72: 402–410.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Full survey

A national survey of oncologists regarding treatment-related infertility and fertility preservation in cancer patients

Doctors.net.uk invites you to take part in a survey regarding cancer patients and fertility on behalf of Oxford Brookes University School of Health and Social Care1.

The aim of this study is to develop a better understanding of oncologists’ knowledge of and attitudes towards fertility preservation for cancer patients. This information will help us in developing optimised fertility care in oncology.

The survey will take about 10 min to complete and all eligible members completing the survey will receive 1000 eSR points.

Please read the following text, which explains the intent of this research:

-

This research is being conducted on behalf of Oxford Brookes University and is being carried out within the code of conduct of the Market Research Society and the British Health-care Business Intelligence Association.

-

The research is not intended to be promotional and any information presented is done so solely to explore reactions to such information.

-

Any information shown during the course of this research should be assumed to represent hypotheses about what can be said about the issue and should not be used to influence decisions outside the research setting.

-

The identity of respondent is confidential: no details of respondents are passed to any third party.

-

Results are aggregated to provide an overall picture of attitudes to the areas being discussed.

Respondents have the right to withdraw from the interview at any time during the interview process and to withhold information as they see fit. Your responses will be otherwise confidential.

The research will form a component of a wider research programme, and therefore the results are intended for publication in anonymized form.

TC1 Are you happy to proceed on this basis?

-

○ Yes

-

○ No

THANK AND CLOSE

1We acknowledge the kind support of Gwendolyn Quinn and Eric Forman. This survey is based in part on a survey developed by Quinn and colleagues: Quinn GP, et al. Physician Referral for Fertility Preservation in Oncology Patients: A National Study of Practice Behaviours. J Clin Oncol. 2009 December 10, 2009;27(35):5952-7 and also on a different survey developed by Forman and colleagues: Forman EJ et al. A nationwide survey of oncologists regarding treatment-related infertility and fertility preservation in female cancer patients. Fertility and Sterility. In Press, Corrected Proof.

Section 1. Medical background information

Q1 Speciality

What is your speciality? (Please tick all that apply)

-

○ Medical oncology

-

○ Clinical oncology

-

○ Surgical oncology

-

○ Other oncology, please specify: ____________________

-

○ None of the above THANK AND CLOSE

Q2 Cancer subspeciality

Do you specialise in a specific cancer site?

Please tick all that apply

-

□ Breast

-

□ Gynaecological

-

□ Urological

-

□ Gastrointestinal

-

□ Lung

-

□ Head and neck

-

□ Haematological

-

□ CNS

-

□ Paediatric

-

□ Sarcomas/soft tissue

-

□ Other: please specify:_____________________

-

○ No specialism

Q2a Patient caseload

How many cancer patients do you usually have in your care in each of the following age ranges:

Please provide an answer for each range:

0–17 years __________

18–45 years __________

46 years and over __________

Q3 Qualification

Which qualifications do you currently have? (Please tick all that apply)

Please tick all that apply

-

□ Bachelor of Medicine/Surgery (e.g., BMBch, MBchB)

-

□ MRCP

-

□ FRCR

-

□ FRCOG

-

□ FRCS

-

□ CCST

-

□ Other: please specify:_____________________

Q4 Grade

What grade are you currently?

Please tick the one answer that best applies to you

-

○ Consultant

-

○ Associate specialist

-

○ Staff grade/specialty doctor

-

○ Specialist registrar years 4+

-

○ Specialist registrar years 1–3

-

○ Other

CLOSE IF CODED OTHER

Q5 Cancer Network

In what Cancer Network is your primary practice located?

Please tick the one answer that best applies to you

-

○ Northern Ireland Cancer Service

-

○ NOSCAN

-

○ SCAN

-

○ WOSCAN

-

○ East riding

-

○ Northern

-

○ Teeside

-

○ Gtr Manchester and Cheshire

-

○ Lancashire and S Cumbria

-

○ Merseyside and Cheshire

-

○ Mid Trent

-

○ North Trent

-

○ Yorkshire

-

○ Arden

-

○ Derby/Burton

-

○ Leicestershire

-

○ Norfolk and Waveney

-

○ West Anglia

-

○ 3 Counties

-

○ Greater Midlands

-

○ Pan Birmingham

-

○ North Wales

-

○ South and West Wales

-

○ South Wales

-

○ Mount Vernon

-

○ North East London

-

○ North London

-

○ West London

-

○ 4 Counties

-

○ Central South Coast

-

○ Channel Islands

-

○ Surrey

-

○ Kent

-

○ Mid Anglia

-

○ South East London

-

○ South Essex

-

○ South West London

-

○ Sussex

-

○ Avon, Somerset and Wiltshire

-

○ Devon and Cornwall

-

○ Dorset

-

○ Other: please specify ________

Section 2. Knowledge of fertility preservation options

Q6 Frequency of contact with fertility preservation options

How often do you encounter patients who have used/are using one of the following fertility preservation options?

Q7 Knowledge of fertility preservation options

How would you describe your level of knowledge of the following fertility preservation options?

Q8 Information need re fertility preservation options

Do you feel you need more knowledge about fertility preservation options?

-

○ Yes

-

○ No

Section 3. Current practices

Q10 Gender distribution of caseload

Approximately, what percentage of your oncology patients aged from 18 to 45 is:

VALIDATION: EACH COLUMN MUST SUM TO 100%; NO ROW VALIDATION

Q11 Fertility preservation age upper threshold - women

Which of the following best represents the age up to which you would consider fertility preservation advice relevant for a woman?

-

○ 40

-

○ 45

-

○ 50

-

○ 55

-

○ 60

-

○ No limit

Q12 Fertility preservation age upper threshold - men

And which of the following best represents the age up to which you would consider fertility preservation advice relevant for a man?

-

○ 40

-

○ 45

-

○ 50

-

○ 55

-

○ 60

-

○ No limit

Q13 Fertility preservation advice giving - frequency

How often do you do each of the following with patients of child-bearing age?

Please tick one answer per row.

ASK Q14 IF Q13_4 NOT CODED NEVER

Q14 Sources of written info provided

If written information is provided, where is this information from?

Please tick all that apply.

-

□ Macmillan Cancer Support

-

□ Hospital’s own information

-

□ Other, please specify: _____________________________

-

○ I do not provide written information to my patients

MAKE ‘I DO NOT PROVIDE...’ AN EXCLUSIVE ANSWER

ASK ALL

Q15 Referral on to fertility specialists

Approximately how many of your patients have been referred to a fertility specialist and/or gone on to have fertility treatment in relation to their cancer treatment in the last year? Please tick one box in each column.

VALIDATION: ONE ANSWER PER COLUMN; NO HORIZONTAL VALIDATION

Q16 Consultation of guidance on fertility issues

Have you consulted any local/ national guidelines for guidance on fertility issues? Please tick all that apply

-

□ Local hospital guidelines

-

□ NICE Fertility guidelines CG11 (2004)

-

□ RCP, RCR and RCOG Guidance - the effects of cancer treatment on reproductive functions (2007)

-

□ Other, please specify: _____________________________

-

○ I have not consulted any guidelines

MAKE ‘I HAVE NOT CONSULTED...’ AN EXCLUSIVE ANSWER

Q17 Availability of fertility preservation on NHS

Is fertility preservation for cancer patients available on the NHS in your local trust?

-

○ Yes

-

○ No

-

○ It depends on the case

-

○ Don’t know

Q18 Proximity to nearest referral point for reproductive medicine

Approximately, how far from your clinic is the nearest reproductive medicine unit/fertility specialist that you can refer to?

Please tick the answer that best applies

-

○ Within the same hospital

-

○ Within the same city

-

○ Within 25 miles

-

○ Within 50 miles

-

○ Within 100 miles

-

○ Further than 100 miles

-

○ Don’t know

Q19 Consultation of guidance on fertility issues

Which of the following statements best describes your professional links with the reproductive medicine unit that is closest to you?

Please tick the answer that best applies

-

○ Very good – I know them well and would know who to contact to refer/discuss a patient

-

○ Good – I do not have much contact but would know who to contact to refer/discuss a patient

-

○ Not very good – I have contacted them in the past and did not receive what I needed

-

○ I would not know – I have not needed to contact them at all

Q20 Attitudes towards fertility preservation

How much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?

RANDOMISE ORDER

Q21 Attitudes towards fertility preservation

To what extent do you think that the following are factors in the importance patients attach to their future fertility?

FOR Q21a-b ROTATE ORDER OF PRECODED RESPONSES, ANCHOR ‘BOTH EQUALLY’

ASK Q21a IF Q21_1=YES

Q21a Gender most concerned about preserving fertility

Do you think women or men are more concerned about preserving fertility?

-

○ Men

-

○ Women

-

○ Both equally

Q21b SES most concerned about preserving fertility

ASK Q21b IF Q21_2=YES

Do you think that patients with a lower or higher socio-economic status (SES) are more concerned about preserving fertility?

-

○ Higher socio-economic status

-

○ Lower socio-economic status

-

○ Both equally

FOR Q21c REVERSE SCALE FOR ALTERNATE RESPONDENTS, ANCHOR ‘ALL LEVELS EQUALLY’

ASK Q21c IF Q21_3=YES

Q21c Educational level most concerned about preserving fertility

Patients from which educational level in your experience are most concerned about future fertility?

-

○ School

-

○ University

-

○ Postgraduate qualification

-

○ All levels equally

ASK Q21d IF Q21_4=YES

Q21d Cultural background most concerned about preserving fertility

In your experience, patients from which cultural backgrounds are most concerned about future fertility?

Please list all that apply

Q22 Cultural background most concerned about preserving fertility

To what extent would you say the following factors influence whether or not you initiate a discussion about fertility with a patient?

SHOW Q23 ON SAME SCREEN AS Q22

Q23 Other influences on initiating discussion regarding fertility preservation

Are there any other factors, beyond those shown above, which will influence you with respect to whether or not you initiate a discussion about fertility with a patient?

Please explain fully

-

○ There are no other factors

MAKE ‘THERE ARE NO OTHER FACTORS’ AN EXCLUSIVE ANSWER

Section 6. Personal information

D1 Gender

Are you...

-

○ Male

-

○ Female

D2 Age

Into which of the following ranges does your age fall?

-

○ Under 30

-

○ 31–40

-

○ 41–50

-

○ 51–60

-

○ 61 or over

D3 Ethnicity

To which of the following ethnic groups would you say you belong?

D4 Religious affiliation

What is your religious background?

D5 Children?

Do you have children?

-

○ Yes

-

○ No

-

○ I do not wish to answer

D6 Children?

Have you or a close family member had cancer?

-

○ Yes

-

○ No

-

○ I do not wish to answer

D7 Other comments

Please add any other comments you may have regarding fertility preservation and your patients:

-

○ I have no further comments to make on this subject

MAKE ‘I HAVE NO FURTHER COMMENTS...’ AN EXCLUSIVE ANSWER

THANK YOU VERY MUCH FOR TAKING THE TIME TO FILL IN THIS SURVEY.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, E., Hill, E. & Watson, E. Fertility preservation in cancer survivors: a national survey of oncologists’ current knowledge, practice and attitudes. Br J Cancer 108, 1602–1615 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.139

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.139

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Efficient pathway for men fertility preservation in testicular cancer or lymphoma: a cross-sectional study of national 2018 data

Basic and Clinical Andrology (2023)

-

Effect of a web-based fertility preservation training program for medical professionals in Japan

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Update Knowledge Assessment and Influencing Predictor of Female Fertility Preservation in Oncologists

Current Medical Science (2022)

-

Sexual and fertility-related adverse effects of medicinal treatment for cancer; a national evaluation among medical oncologists

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Adult cancer patients and parents of younger cancer patients have little information about fertility preservation: a survey of knowledge and attitude

Middle East Fertility Society Journal (2021)