Abstract

Background:

Prognostic factors for progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and long-term OS (⩾30 months) were investigated in sunitinib-treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Methods:

Data were pooled from 1059 patients in six trials. Baseline variables, including ethnicity, were analysed for prognostic significance by Cox proportional-hazards model.

Results:

Median PFS and OS were 9.7 and 23.4 months, respectively. Multivariate analysis of PFS and OS identified independent predictors, including ethnic origin, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, time from diagnosis to treatment, prior cytokine use, haemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase, corrected calcium, neutrophils, platelets, and bone metastases (OS only). Characteristics of long-term survivors (n=215, 20%) differed from those of non-long-term survivors; independent predictors of long-term OS included ethnic origin, bone metastases, and corrected calcium. There were no differences in PFS (10.5 vs 7.2 months; P=0.1006) or OS (23.8 vs 21.4 months; P=0.2135) in white vs Asian patients; however, there were significant differences in PFS (10.5 vs 5.7 months; P<0.001) and OS (23.8 vs 17.4 months; P=0.0319) in white vs non-white, non-Asian patients.

Conclusion:

These analyses identified risk factors to survival with sunitinib, including potential ethnic-based differences, and validated risk factors previously reported in advanced RCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Sunitinib is an orally administered, multi-targeted inhibitor of receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor, and other tyrosine kinases (Chow and Eckhardt, 2007). Sunitinib demonstrated efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) who progressed on cytokine therapy (Motzer et al, 2006a, 2006b), and was the first targeted agent to show benefit compared with cytokine therapy in treatment-naive patients with metastatic RCC (Motzer et al, 2009). In a randomised phase III trial, sunitinib demonstrated superior efficacy to interferon (IFN)-α as first-line metastatic RCC therapy with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 11 vs 5 months (P<0.001), respectively, (Motzer et al, 2009). In addition, median overall survival (OS) with sunitinib was >2 years (Motzer et al, 2009), establishing sunitinib as a reference standard of care. As such, new tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), as well as novel combinations, should be compared with sunitinib in phase III trials. Accordingly, identification of prognostic factors is important in clinical trial design and interpretation.

Here, we report a retrospective analysis of prognostic factors for PFS and OS in 1059 metastatic RCC patients treated with sunitinib in six clinical trials (Motzer et al, 2006a, 2006b, 2009, 2012; Escudier et al, 2009; Barrios et al, 2012). The features studied and compared include those reported in the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) model (which was developed in the era before targeted therapy; Motzer et al, 2002), as well as a similar model recently reported by Heng et al (2009), which was developed using a database of patients treated with a variety of VEGF-targeted drugs.

We explored ethnic-based differences in baseline characteristics and survival, as there have been differences in outcome and tolerability reported to sunitinib by ethnicity (Hong et al, 2009; Lee et al, 2009; Tomita et al, 2010). We identified a group of patients with long-term OS, defined as OS of ⩾30 months, and examined pretreatment features in this cohort of patients. An ad hoc analysis of ethnic-based differences in tolerability was also conducted.

Materials and methods

Patients

The population comprised patients aged ⩾18 years with the following eligibility criteria: histologically confirmed metastatic RCC, evidence of measurable disease according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST; Therasse et al, 2000), no known presence of brain metastases, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1 (or Karnofsky performance status ⩾70 in one trial; Motzer et al, 2012), and adequate organ function.

Study design and treatments

This retrospective analysis investigated prognostic factors for PFS, OS, and long-term OS using pooled data from 1059 patients treated with sunitinib in six prospective trials for advanced RCC (Motzer et al, 2006a, 2006b, 2009, 2012; Escudier et al, 2009; Barrios et al, 2012). Sunitinib was administered orally at a starting dose of either 50 mg per day for 4 consecutive weeks followed by 2 weeks off treatment in repeated 6-week cycles (schedule 4/2; n=690; 65%) or 37.5 mg per day on a continuous once-daily dosing schedule (n=369; 35%). Treatment continued until disease progression, lack of clinical benefit, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent.

The studies were run in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines (or the Declaration of Helsinki) and applicable local regulatory requirements and laws, and approved by the institutional review boards or independent ethics committees of each participating centre (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00267748, NCT00137423, NCT00083889, NCT00077974, NCT00054886, NCT00338884).

Statistical methods

A multivariate Cox regression model was used to analyse potential baseline prognostic variables for PFS, OS, and long-term OS (i.e., OS ⩾30 months). Previously identified prognostic factors, including those in the MSKCC and Heng et al risk models (Motzer et al, 2002; Heng et al, 2009), were investigated. Each variable was investigated by univariate and then multivariate analysis, using a stepwise algorithm, in which factors with P<0.2 by Wald χ2 test were included in the multivariate analysis. Further elimination was applied within the multivariate analysis to identify variables significant at P<0.05.

Median PFS and OS were estimated by Brookmeyer and Crowley method and compared between subgroups using a Wald χ2 test. Tumour response was investigator-assessed by RECIST on schedules specified for each trial (initially every 4–6 weeks, increasing to every 8–12 weeks after approximately 6 months). Progression-free survival was defined as the time from the start of treatment or random assignment to tumour progression or death owing to any cause, and OS was defined as the time from the start of treatment or random assignment to death owing to any cause.

Within the ethnic subanalyses, baseline characteristics were separately compared between white patients vs Asian patients and vs non-white, non-Asian patients using either a Fisher’s exact test, t-test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Multivariate analyses of ethnic differences in PFS and OS were conducted using the Brookmeyer and Crowley method to estimate median values and a two-sided unstratified log-rank test to compare subgroups.

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients with and without long-term OS by either a Pearson or Mantel–Haenszel χ2 test (with Fisher’s exact test used when sample size requirements for the χ2 test were not met).

An ad hoc analysis of ethnic-based differences in the occurrence of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) was conducted. AEs were recorded regularly in each trial and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs, version 3.0 (version 2.0 in one trial; Motzer et al, 2006a). Patient subgroups were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Patients, treatment, and outcome

The majority of the 1059 sunitinib-treated patients were men (70%) and the median age was 60 years (Table 1). Eighty-three percent were white, 7% were Asian, and 6% were non-white, non-Asian (e.g., black or Hispanic patients).

Age, gender, and performance status were similar between white and Asian patients (Table 2); however, more white patients compared with Asian patients had prior nephrectomy (83% vs 24%; P<0.001) and liver metastases at baseline (24% vs 10%; P=0.007). White patients compared with non-white, non-Asian patients (Table 2) were older (61 vs 57 years, respectively; P=0.003) and had higher rates of prior nephrectomy (83% vs 68%; P=0.05) and cytokine use (25% vs 14%; P=0.037), respectively. The reason for the lower than expected nephrectomy rate in the Asian population is unknown.

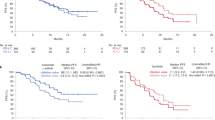

Sunitinib was administered in either the first-line (n=783; 74%) or cytokine-refractory (n=276; 26%) setting. Median PFS and OS in all 1059 patients were 9.7 months (95% CI, 8.4–10.5 months) and 23.4 months (95% CI, 21.2–25.4 months), respectively (Figure 1).

Prognostic factors for PFS and OS with sunitinib

The following factors, identified with P<0.2 by univariate analysis, were subsequently included in the multivariate analysis (even if they were nonsignificant (NS) for PFS and/or OS): ECOG performance status, baseline lactate dehydrogenase, baseline haemoglobin, baseline-corrected calcium, time from diagnosis to treatment (all from the MSKCC prognostic model; Motzer et al, 2002), and also: age (NS for PFS/OS), ethnic origin, prior radiation (NS for PFS), baseline platelets, liver metastases (NS for PFS), lung metastases (NS for PFS), bone metastases, baseline alkaline phosphatase, baseline neutrophils, body mass index (BMI; overweight), body surface area (NS for PFS), prior medications (NS for PFS/OS), systolic blood pressure, and prior cytokine use.

The multivariate analysis identified 9 and 10 independent predictors for PFS and OS, respectively, (Table 3), including ethnic origin for both PFS and OS, and bone metastases for OS only (Figure 2). For example, white patients had a superior PFS to non-white patients with a median of 10.5 months (95% CI, 9.7–10.9 months) vs 6.6 months (5.4–7.8 months), respectively, (hazard ratio (HR), 0.598; 95% CI, 0.459–0.781; P=0.0002; Table 3).

There were no statistically significant differences in PFS or OS in white patients compared with Asian patients, irrespective of the first-line or cytokine-refractory treatment setting, although PFS was numerically longer in white patients (Table 4). However, there were significant differences in PFS and OS in white patients compared with non-white, non-Asian patients. In white patients, median PFS was 10.5 months (95% CI, 9.7–10.9 months) vs 5.7 months (95% CI, 5.1–9.7) in non-white, non-Asian patients (HR, 0.575; 95% CI, 0.435–0.761; P<0.001); similarly, median OS was 23.8 months (95% CI, 21.8–26.2 months) vs 17.4 months (95% CI, 12.1–23.6 months), respectively (HR, 0.701; 95% CI, 0.506–0.972; P=0.0319).

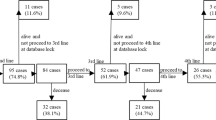

Prognostic factors for long-term OS with sunitinib

Overall, 215 patients (20%) survived ⩾30 months with sunitinib. Baseline characteristics differed between long-term survivors and other patients (Table 5), including risk status based on MSKCC prognostic criteria (Motzer et al, 2002; P<0.0001). For example, 70% of the long-term survivors had favourable risk features compared with 31% of non-long-term survivors; in contrast, 42% and 5% of the non-long-term survivors had intermediate and poor risk features compared with 28% and 0% of long-term survivors, respectively. The proportion of patients without prior cytokine therapy was significantly higher among long-term compared with non-long-term survivors (79% vs 71%, respectively; P=0.0170), although previously treated patients also had long-term survival on sunitinib.

Independent prognostic factors were identified by multivariate analysis in patients with long-term OS (Table 6) and included ethnic origin, baseline bone metastases, and baseline-corrected calcium. For example, amongst this subgroup of long-term survivors, those without baseline bone metastases had a median OS of 54.5 months (95% CI, 47.8 months to not reached) compared with 42.7 months (95% CI, 37.5 months to not reached) for those with bone metastases (HR, 2.337; 95% CI, 1.275–4.285; P=0.0061).

Ethnic-based differences in tolerability

Although many common treatment-emergent AEs occurred at similar rates regardless of ethnicity, there were significant ethnic-based differences in almost half of all such events (Table 7). The majority of differences occurred between white and Asian patients. For example, white patients experienced more nausea (55% vs 40%), dysguesia (41% vs 26%), and decreased appetite (36% vs 17%), compared with Asian patients, respectively, who experienced more hand-foot syndrome (28% vs 70%) and mucosal inflammation (26% vs 40%; all P<0.05). Compared with non-white, non-Asian patients, white patients experienced significantly more dyspepsia (33% vs 18%) and stomatitis (30% vs 14%; both P<0.05). Tolerability was similar regardless of first-line or cytokine-refractory treatment setting (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis conducted in 1059 patients with metastatic RCC identified pretreatment clinical features that were associated with shorter survival to sunitinib. In addition, we identified a cohort of patients with a relatively long-term survival.

The pretreatment clinical features associated with sunitinib outcome are consistent with those previously reported in the MSKCC model (Motzer et al, 2002) and by Heng et al (2009); the latter obtained using data from patients outside clinical trials in a real-world setting. Small differences between factors identified previously in MSKCC analyses (Motzer et al, 2002) or more recently Heng et al (2009) and Choueiri et al (2007) in series comprising mixed targeted agents (sunitinib, sorafenib, bevacizumab (Choueiri et al, 2007; Heng et al, 2009), and axitinib (Choueiri et al, 2007)) likely represent a more select patient population and methodological differences. The commonality between factors suggests that these are not specific for a given treatment. Instead, these factors reflect a more aggressive underlying RCC biology.

The importance of these factors as associated with a shorter OS was demonstrated in the Cox proportional-hazards analysis performed for the phase III trial of sunitinib vs IFN. The analyses encompassed pretreatment clinical features plus the treatment arms as variables (Motzer et al, 2009). Although treatment was an independent variable, with sunitinib significantly better than IFN (HR, 0.764; P=0.0096), the pretreatment factors maintained their significance for predicting shorter survival, independent of treatment. For example, as comparison, the HRs for the MSKCC risk features were: anaemia (1.984), low performance status (1.942), time from diagnosis to treatment of <1 year (1.742), high-corrected calcium (2.146), and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (2.000). Tumour biology, reflected by these features, continues to drive OS, independent of the effect of sunitinib. As such, a better understanding of RCC biology is a priority. A tumour-specific biomarker(s) could enhance or replace prognostic models based on clinical features.

Like the analysis reported here, presence of bone metastasis was associated with shorter survival in an analysis with everolimus (Motzer et al, 2010). In that study, the population comprised patients who progressed on sunitinib and/or sorafenib. Clinically, patients treated with targeted agents may often first show signs of progression in bone metastases (Plimack et al, 2009). This could be a consequence of reduced vascularity in bone, as these agents are anti-angiogenesis drugs or some other aetiology. Studies that integrate radiation or other tumour-ablative techniques could be useful in treating RCC bone metastases. One multi-targeted TKI, cabozantinib, has achieved remarkable responses in bone metastases for prostate cancer (Hussain et al, 2011) and one phase Ib trial suggests a high level of activity in RCC (Choueiri et al, 2012). Studies with cabozantinib in metastatic RCC patients with bone metastases would be of high interest.

There were no significant differences in survival in white vs Asian patients. However, there was a trend for longer PFS in white patients compared with Asian patients, and white patients had a significantly longer PFS and OS compared with non-white, non-Asian patients. The latter finding could be linked to socioeconomic differences, which influenced outcome. These findings may also be accounted for by differences in baseline characteristics. However, given the extent of incomplete data, these differences and their potential impact on outcome require further investigation. Another possible explanation for efficacy differences were differing rates of prior nephrectomy, an independent predictor of survival in both Asian and non-Asian patients (Naito et al, 2010; Patil et al, 2011). In the trials included in our analysis, the incidence of nephrectomy was much lower in Asian (24%) and non-white, non-Asian (68%) patients, compared with white patients (83%).

Differences in ethnic-based treatment tolerability may have also had a role. For example, ad hoc analyses indicated that several AEs occurred significantly more often in Asian patients, relative to white patients, such as hand-foot syndrome that occurred in 70% of Asian patients compared with 28% of white patients (P<0.001). This is consistent with previous studies of sunitinib and sorafenib in Asian RCC patients, including Japanese, Chinese, and Korean patients (Sun et al, 2008; Hong et al, 2009; Lee et al, 2009; Tomita et al, 2010; Naito et al, 2011). For example, the incidences of hand-foot syndrome and hypertension were higher in Japanese and Chinese patients receiving sorafenib, in comparison with Western patients; similarly, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia occurred more frequently in Japanese and Korean patients receiving sunitinib. Such differences in tolerability in our study may have led to disparities in drug exposure due to higher discontinuation and/or dose reduction rates, which, in turn, may have diminished clinical benefit. On the other hand, several differences favoured Asian over white patients, and differences were less prominent between white and non-white, non-Asian patients, thus confounding a simple interpretation based on AEs only. Inter-ethnic pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenomic differences may explain the variation in tolerability and are under study (Kim et al, 2011).

Although this large database of 1059 patients enroled to six clinical trials over 6 years provides a robust data set to analyse, study limitations are recognised. In addition to the usual issues associated with a retrospective analysis, the following may have confounded or led to difficulty in interpreting the results: data were missing for a significant proportion of patients in some categories of baseline information and subpopulations (e.g., risk factor data were missing for 40% of Asian patients); differences in sunitinib treatment schedules were not investigated for prognostic influence; there were imbalances in the numbers of patients in each ethnic subgroup and in some baseline characteristics; patients in clinical trials may represent a selective population; and, given the changes in the RCC treatment landscape during and after conduct of these trials, survival estimates may not be accurate representations of potential clinical benefit.

In conclusion, this analysis identified risk factors to survival with sunitinib and validated risk factors previously reported in advanced RCC. Potential ethnic-based differences in survival with sunitinib were identified. These factors may be applied to clinical trial design (e.g., patient eligibility and stratification) and interpretation of survival.

Change history

25 June 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Barrios CH, Hernandez-Barajas D, Brown MP, Lee SH, Fein L, Liu JH, Hariharan S, Martell BA, Yuan J, Bello A, Wang Z, Mundayat R, Rha SY (2012) Phase II trial of continuous once-daily dosing of sunitinib as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 118: 1252–1259.

Choueiri TK, Garcia JA, Elson P, Khasawneh M, Usman S, Golshayan AR, Baz RC, Wood L, Rini BI, Bukowski RM (2007) Clinical factors associated with outcome in patients with metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. Cancer 110: 543–550.

Choueiri TK, Pal SK, McDermott DF, Ramies DA, Morrissey S, Lee Y, Miles D, Holland JS, Dutcher JP (2012) Activity of cabozantinib (XL184) in patients (pts) with metastatic, refractory renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol 30 (Suppl 5): (abstract 364).

Chow LQ, Eckhardt SG (2007) Sunitinib: from rational design to clinical efficacy. J Clin Oncol 25: 884–896.

Escudier B, Roigas J, Gillessen S, Harmenberg U, Srinivas S, Mulder SF, Fountzilas G, Peschel C, Flodgren P, Maneval EC, Chen I, Vogelzang NJ (2009) Phase II study of sunitinib administered in a continuous once-daily dosing regimen in patients with cytokine-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 4068–4075.

Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, Eigl BJ, Ruether JD, Cheng T, North S, Venner P, Knox JJ, Chi KN, Kollmannsberger C, McDermott DF, Oh WK, Atkins MB, Bukowski RM, Rini BI, Choueiri TK (2009) Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 27: 5794–5799.

Hong MH, Kim HS, Kim C, Ahn JR, Chon HJ, Shin SJ, Ahn JB, Chung HC, Rha SY (2009) Treatment outcomes of sunitinib treatment in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients: a single cancer center experience in Korea. Cancer Res Treat 41: 67–72.

Hussain M, Smith MR, Sweeney C, Corn PG, Elfiky A, Gordon MS, Haas NB, Harzstark AL, Kurzrock R, Lara P, Lin C, Sella A, Small EJ, Spira AI, Vaishampayan UN, Vogelzang NJ, Scheffold C, Ballinger MD, Schimmoller F, Smith DC (2011) Cabozantinib (XL184) in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): results from a phase II randomized discontinuation trial. J Clin Oncol 29 (Suppl): (abstract 4516).

Kim HS, Hong MH, Kim K, Shin SJ, Ahn JB, Jeung HC, Chung HC, Koh Y, Lee SH, Bang YJ, Rha SY (2011) Sunitinib for Asian patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: a comparable efficacy with different toxicity profiles. Oncology 80: 395–405.

Lee S, Chung HC, Mainwaring P, Ng C, Chang JWC, Kwong P, Li RK, Sriuranpong V, Ton CK, Pitman Lowenthal S (2009) An Asian subpopulation analysis of the safety and efficacy of sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Suppl 7: 428.

Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P, Mazumdar M (2002) Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 20: 289–296.

Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, Grünwald V, Thompson JA, Figlin RA, Hollaender N, Kay A, Ravaud A on behalf of the RECORD-1 Study Group (2010) Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer 116: 4256–4265.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Olsen MR, Hudes GR, Burke JM, Edenfield WJ, Wilding G, Agarwal N, Thompson JA, Cella D, Bello A, Korytowsky B, Yuan J, Valota O, Martell B, Hariharan S, Figlin RA (2012) Randomized phase II trial of sunitinib on an intermittent versus continuous dosing schedule as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 30: 1371–1377.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Pili R, Bjarnason GA, Garcia-del-Muro X, Sosman JA, Solska E, Wilding G, Thompson JA, Kim ST, Chen I, Huang X, Figlin RA (2009) Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 3584–3590.

Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, Hudes GR, Wilding G, Figlin RA, Ginsberg MS, Kim ST, Baum CM, DePrimo SE, Li JZ, Bello CL, Theuer CP, George DJ, Rini BI (2006a) Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 24: 16–24.

Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, Curti BD, George DJ, Hudes GR, Redman BG, Margolin KA, Merchan JR, Wilding G, Ginsberg MS, Bacik J, Kim ST, Baum CM, Michaelson MD (2006b) Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA 295: 2516–2524.

Naito S, Tsukamoto T, Murai M, Fukino K, Akaza H (2011) Overall survival and good tolerability of long-term use of sorafenib after cytokine treatment: final results of a phase II trial of sorafenib in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int 108: 1813–1819.

Naito S, Yamamoto N, Takayama T, Muramoto M, Shinohara N, Nishiyama K, Takahashi A, Maruyama R, Saika T, Hoshi S, Nagao K, Yamamoto S, Sugimura I, Uemura H, Koga S, Takahashi M, Ito F, Ozono S, Terachi T, Naito S, Tomita Y (2010) Prognosis of Japanese metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients in the cytokine era: a cooperative group report of 1463 patients. Eur Urol 57: 317–325.

Patil S, Figlin RA, Hutson TE, Michaelson MD, Négrier S, Kim ST, Huang X, Motzer RJ (2011) Prognostic factors for progression-free and overall survival with sunitinib targeted therapy and with cytokine as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 22: 295–300.

Plimack ER, Tannir N, Lin E, Bekele BN, Jonasch E (2009) Patterns of disease progression in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with antivascular agents and interferon: impact of therapy on recurrence patterns and outcome measures. Cancer 115: 1859–1866.

Sun Y, Na Y, Yu S, Zhang Y, Zhou A, Li N, Yang L, Lou G (2008) Sorafenib in the treatment of Chinese patients with advanced renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 26 (May 20 Suppl): (abstract 16127).

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 205–216.

Tomita Y, Shinohara N, Yuasa T, Fujimoto H, Niwakawa M, Mugiya S, Miki T, Uemura H, Nonomura N, Takahashi M, Hasegawa Y, Agata N, Houk B, Naito S, Akaza H (2010) Overall survival and updated results from a phase II study of sunitinib in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 40: 1166–1172.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients and their families, and the investigators, research nurses, study coordinators, and operations staff. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Andy Gannon at ACUMED (New York, New York) with funding from Pfizer Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

RJ Motzer reported receiving consultancy fees from Pfizer and research funding from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, AVEO Pharmaceuticals, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. B Escudier reported receiving honoraria from Pfizer. R Bukowski reported receiving consultancy fees, honoraria, and legal fees from Pfizer. BI Rini reported receiving consultancy fees and research funding from Pfizer. TE Hutson reported receiving research funding, consultancy fees, and honoraria from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AVEO Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. CH Barrios reported receiving research funding, consultancy fees, and honoraria from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis. ME Gore reported receiving advisory board fees and honoraria from Pfizer. X Lin, K Fly and E Matczak are full-time employees of Pfizer and hold Pfizer stock.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Motzer, R., Escudier, B., Bukowski, R. et al. Prognostic factors for survival in 1059 patients treated with sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 108, 2470–2477 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.236

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.236

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prognostic model for overall survival that includes the combination of platelet count and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio within the first six weeks of sunitinib treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma

BMC Cancer (2022)

-

Lysosomal protein transmembrane 5 promotes lung-specific metastasis by regulating BMPR1A lysosomal degradation

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Dynamic serum biomarkers to predict the efficacy of PD-1 in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Cancer Cell International (2021)

-

A new scenario in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a SOG-GU consensus

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2020)

-

Patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who benefit from axitinib dose titration: analysis from a randomised, double-blind phase II study

BMC Cancer (2019)