Abstract

Background:

Higher-grade inflammatory infiltrate is a promising marker for better prognosis in colorectal cancer (CRC). However, the knowledge on the interrelationships between different inflammatory cells and classifications is fragmentary.

Methods:

We analysed the densities of eight types of inflammatory cells in a prospectively recruited group of 117 CRC patients and determined their interrelationships and contributions to Klintrup–Mäkinen (K–M) score of overall peritumoural inflammation. We characterised the inflammatory infiltrate in relation to stage and recurrences in 24-month follow-up.

Results:

There were high positive correlations between the inflammatory cell densities, with the exception of mast cells and CD1a+ immature dendritic cells. High K–M score associated with high peri- and intratumoural densities of CD3+, CD8+, CD68+, CD83+, and FoxP3+ cells and neutrophils. Advanced stage associated with low K–M score, as well as low CD3+, CD8+, CD83+, and FoxP3+ cell counts, of which low K–M score, low CD3+ T-cell count, and low FoxP3+ T-cell count were linked to higher recurrence rate.

Conclusion:

The density of CRC inflammatory infiltrate declines as stage advances. Especially, low K–M score and low T-cell counts predict higher recurrence rate. The high positive correlations between the individual inflammatory markers support the value of overall inflammatory reaction scoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It is well acknowledged that inflammation and immune system contribute to cancer pathogenesis (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). In colorectal cancer (CRC), one of the leading causes of cancer deaths worldwide (Jemal et al, 2009), heavier inflammatory infiltrate in tumour area has been associated with better prognosis in an assemblage of studies (Roxburgh and McMillan, 2012), emphasising the significance of an effective immune response in controlling tumour progression (Schreiber et al, 2011).

However, the lack of a standardised analysis method has been a major concern (Galon et al, 2012; Roxburgh and McMillan, 2012), and so far, none of the proposed immunohistochemical cell markers (Naito et al, 1998; Pages et al, 2005; Galon et al, 2006; Väyrynen et al, 2012b) or inflammatory classifications based on inspecting haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides (Jass, 1986; Klintrup et al, 2005; Ogino et al, 2009) have been incorporated into routine clinical practice. There are only limited amount of data on the interrelationships between different inflammatory cell types (Nagtegaal et al, 2001) and inflammatory cell reaction grading methods (Roxburgh et al, 2009b; Richards et al, 2012a) in CRC, which would be essential in evaluating their relative significance.

Klintrup–Mäkinen (K–M) score for peritumoural inflammation utilising H&E slides has been acknowledged as one of the most promising overall inflammatory reaction grading systems in CRC (Roxburgh and McMillan, 2012). It has been shown to be reproducible and to harbour stage-independent prognostic value in several studies (Klintrup et al, 2005; Roxburgh et al, 2009a, 2009b; Richards et al, 2012a), exceeding the value of Jass classification (Roxburgh et al, 2009b) and individual inflammatory cell counts from H&E slides (Richards et al, 2012a). Although being linked with heavy peritumoural macrophage and lymphocyte infiltration based on evaluations utilising H&E slides (Klintrup et al, 2005; Richards et al, 2012a), the distinct cell types contributing to high K–M score still remain equivocal.

In this study we systematically quantitated the densities of eight inflammatory cell types from intra- and peritumoural regions. We analysed a prospectively recruited group of 117 CRC patients utilising an accurate image analysis-based method (Väyrynen et al, 2012b). The main aims of the study were to enlighten the mutual relationship between different inflammatory cell types in CRC and to clarify the contributions of individual cell types to K–M-classification of peritumoural inflammation. As a deficient mismatch repair (MMR) system is known to contribute to the CRC-associated inflammatory reaction (Smyrk et al, 2001), we also characterised the immune cell infiltration in relation to MMR screening status.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study was based on an earlier described prospectively recruited group of 149 CRC patients, who had signed an informed consent for the study and were operated in Oulu University Hospital in 2006–2010 (Kantola et al, 2012). The data collection procedures and analysis methods were designed before the start of the collection of study material. The clinical details of the patients were collected from the case records, including the data on recurrences by the 24-month follow-up visit. Of the 149 patients, 32 (21.5%) patients who received preoperative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy (RT/CRT) were excluded as RT/CRT is a potential confounding factor, affecting especially the inflammatory parameters of the tumours (Nagtegaal et al, 2002). Thus, the final study included 117 (78.5%) of 149 CRC patients (Table 1). The study design was approved by the Ethical Committee of Oulu University Hospital (58/2005, 184/2009).

Histopathological analysis

The samples from surgical specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution and embedded in paraffin, and 5 μm sections were stained with H&E. Staging was done according to TNM6 (Sobin and Wittekind, 2002) and grading according to the WHO criteria (Hamilton et al, 2000). The TNM6 was chosen to allow better comparability with previous studies. We evaluated peritumoural inflammatory reaction from H&E slides according to the K–M criteria, where 0 denoted no increase of inflammatory cells, 1 denoted mild and patchy increase of inflammatory cells, 2 denoted a band-like infiltrate at the invasive margin with some evidence of destruction of cancer cell islets, and 3 denoted a very prominent inflammatory reaction with frequent destruction of cancer cell. These scores were then classified into low grade (0–1) and high grade (2–3) (Klintrup et al, 2005).

TMA construction

We constructed a tissue microarray (TMA) for the analysis of inflammatory cell densities. We used the H&E slides to select optimal sample locations. Depending on the size of the tumour, we manually sampled 1–4 (median 3) cores of 3.0 mm diameter for each case yielding an overall tumour area of 7.1–28.3 mm2. Of these cores, 1–3 (median 2) were taken from the invasive front of the tumour containing the point of deepest invasion and the rest from intratumoural locations with an aim to avoid necrotic areas.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections (3.5 μm) cut from paraffin-embedded specimens were deparaffinised in xylene and rehydrated through graded alcohol series. For antigen retrieval, the sections were pretreated with TRIS-EDTA, pH 9.0, in a microwave oven at 800 W for 2 min and at 150 W for 15 min. After neutralising endogenous peroxidase activity, the sections were incubated at room temperature with diluted primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 1). Bound antibodies were detected using EnVision system (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark). The 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used as the chromogen and haematoxylin as the counterstain. The MMR enzyme immunohistochemistry was conducted as described previously (Väyrynen et al, 2012a).

We counted the inflammatory cells using an earlier described computer-based method (Väyrynen et al, 2012b). We photographed the sections from different locations (peritumoural, intratumoural stromal and intratumoural epithelial) with Olympus DP25 camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) attached to Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) utilising × 20 and × 10 objectives. We used ImageJ-based (Abramoff et al, 2004) set of programmes in counting the positive cells based on their size, shape, and the intensity of positivity (Väyrynen et al, 2012b). We counted intraepithelial immune cells (CD3 and CD8) manually from the captured images because of the inadequacy of the automatic cell counting to segregate the intraepithelial cells from those in the stroma. All the cell counts were expressed as cells mm−2. The MMR screening status was evaluated by MLH1 and MSH2 immunohistochemistry as described earlier (Väyrynen et al, 2012a).

Statistical analyses

Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean (s.d.), whereas other continuous variables are presented as median (IQR). The statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were used in determining the correlations between different immune cell types. A logarithmic transformation was applied to variables with positive skewness. Nearest neighbour method with standardised squared Euclidean distance was applied in hierarchical clustering of different inflammatory cell variables. The statistical significances of the associations between immune cells and K–M score, MMR screening status, and stage were analysed by Mann–Whitney U-test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Cross-tabulation and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were used in determining the associations between K–M score, MMR screening status, and stage. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis for optimal cutoff points, Kaplan–Meier method, and log-rank test for statistical significance were used in the recurrence analysis. The P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of immune cell infiltration

Of the 117 cases, 65 (55.6%) showed high-grade K–M score, signifying a band-like inflammatory infiltrate at the invasive margin with evidence of cancer cell destruction. Immunohistochemistry was used to further characterise the inflammatory infiltrate and it was successful in all 117 cases (Figure 1). The CD3+ T cells were the most frequent in all the tumour locations, followed by CD68+ cells (mainly monocyte–macrophage lineage), CD8+ T cells, and FoxP3+ T cells. At the invasive front, the median CD8+ and FoxP3+ T-cell counts were 30.4% and 26.7% of the amount of CD3+ T cells, respectively, and in the intratumoural stroma, 19.3% and 29.8%, respectively. Peritumoural inflammatory infiltrate was, in general, heavier than intratumoural stromal infiltrate.

Representative images of immunohistochemical determination of eight inflammatory cell types in colorectal cancer: CD3 for T cells, CD8 for cytotoxic T cells, FoxP3 for regulatory T cells, CD68 for monocyte–macrophage lineage cells, CD83 for mature dendritic cells, CD1a for immature dendritic cells, mast cell tryptase for mast cells, and neutrophil elastase for neutrophilic granulocytes.

Interrelationships between inflammatory cells and their contributions to K–M classification

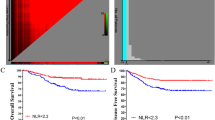

We analysed the interrelationships between different inflammatory cells by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients (Table 2) and by hierarchical clustering of the inflammatory cell markers (Figure 2). Different inflammatory cells had high positive correlations with each other, except for mast cells and CD1a+ immature dendritic cells (DCs), which also clustered furthest from T cells in hierarchical clustering. The CD83+ mature DCs clustered with T cells (Figure 2), highlighting their importance for the adaptive immune response against the tumour. Peritumoural and intratumoural cell counts of each cell type showed substantial concordance, with Pearson’s r varying from 0.434 (CD83) to 0.714 (CD3).

Dendrogram for hierarchical clustering of eight inflammatory cells in CRC. Nearest neighbour method with standardised squared Euclidean distance was used. Mast cells and CD1a+ immature DCs clustered furthest from other cell types (at the bottom). These cell types also had the weakest associations with stage (Table 4). Instead, T cells, forming a cluster at the top along with CD83+ mature DCs, had the highest associations with stage (Table 4), recurrences (Table 5), and MMR deficiency (Supplementary Table 4), supporting their importance in CRC defence.

The contributions of the individual inflammatory cells to K–M score are presented in Table 3. High K–M score associated with higher densities of CD3+, CD8+, and FoxP3+ T cells, CD68+ cells, CD83+ mature DCs, and neutrophils. Although based on the evaluation of the inflammatory reaction at the invasive front, the classification notably showed excellent correlation with the densities of intratumoural – in addition to peritumoural – inflammatory cells.

Immune cell infiltration in relation to stage and MMR screening status

Higher TNM stage – in particular, stage IV denoting the presence of distant metastases – associated with generally lower immune cell densities (Table 4), especially, with lower densities of FoxP3+, CD3+, and CD8+ T cells, as well as CD83+ DCs, all of which had been shown to be related to higher K–M score (Table 3). Thus, unsurprisingly, K–M score also inversely correlated with stage (P=1.2E−3; Supplementary Table 2). Conversely, mast cells, stromal CD68+ cells, stromal CD1a+ cells, and stromal neutrophils did not have significant associations with stage. With the exception of mast cells, peritumoural immune cell densities had higher associations with stage than intratumoural densities of the same cell types.

The MMR-deficient cases had a trend towards higher K–M score (P=0.062; Supplementary Table 3), and in the detailed analysis, MMR deficiency associated with increased amounts of intra- and peritumoural CD3+ and CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Table 4).

Recurrence analysis

Finally, we carried out a 24-month recurrence analysis for 80 (68.4%) of 117 patients, of whom 15 (18.8%) had a recurrence. Of the 117 patients, 22 (18.8%) were excluded because they underwent a palliative operation and 15 (12.8%) were excluded because they did not have 24-month follow-up data available. The ROC analysis was used to compare the discriminatory capacity of different variables as well as in setting optimal cutoff points (Table 5). Four-tiered K–M classification, FoxP3, and CD3 yielded the highest areas under the curves (AUCs). Log rank test indicated significant associations with recurrences for four-tiered K–M score, peritumoural T cells (CD3+), and stromal and peritumoural FoxP3+ T cells (Table 5). Also, several other cell types showed tendencies for lower recurrence rates in higher cell densities (AUC >0.500) but lacked statistical significance in the short follow-up. Currently, the short follow-up did not enable a construction of sensible multivariate survival models.

Discussion

This study aimed to enlighten the interrelationships between different inflammatory cell types and K–M overall classification for peritumoural inflammation in CRC. To our knowledge, this is so far the most extensive study on this subject, including markers of both adaptive (CD3, CD8, and FoxP3) and innate immunity (CD68, neutrophil elastase, and mast cell tryptase), as well as antigen prsenting cells (APCs) (CD1a, CD68, and CD83) serving as a link between the two (Banchereau et al, 2000). We found that most constituents of CRC inflammatory infiltrate show notable positive correlations between each other and the K–M score. This finding, along with the capability of K–M score in predicting recurrences, supports the value of overall inflammatory assessments.

The accurate, computer-based cell counting method (Väyrynen et al, 2012b) allowed us to look into the role of individual cell types in CRC-associated immune responses. We utilised a TMA that was specifically built for immune cell evaluations from different tumour locations. The substantial tumour area of 7.1–28.3 mm2 – for comparison, for example, 12.5–50.0 times larger than in the noteworthy study by Nosho et al (2010) assessing the prognostic effect of intraepithelial T cells – decreased the risk of sampling error, whereas the avoidance to sample necrotic areas reduced the potential impact of necrosis as a confounding factor (Richards et al, 2012b). Compared with whole-tissue samples, the TMA enabled the standardisation of analysed locations that was beneficial in the study of interrelationships between immune cells.

T lymphocytes, the hallmark of cell-mediated adaptive immunity, are considered essential in tumour immunosurveillance (Schreiber et al, 2011), as shown in dozens of reports of their prognostic significance in CRC (Roxburgh and McMillan, 2012), as well as in other solid tumours (Fridman et al, 2012). Our study included CD3 as pan-T-cell marker, CD8 representing cytotoxic T cells, and FoxP3 as a marker for regulatory T (TReg) cells, all of which have been associated with better survival and stage-independent prognostic value in CRC (Naito et al, 1998; Galon et al, 2006; Salama et al, 2009; Frey et al, 2010). Still, some discrepancy exists for the significance of TReg cells. High TReg cell infiltration has been linked with poor survival in, for example, ovarian (Curiel et al, 2004) and breast cancer (Bates et al, 2006), which is in accordance with the role of TReg cells in dampening immune response (Zou, 2006). Moreover, some studies have failed to show an association between FoxP3+ T-cell infiltration and survival in CRC (Sinicrope et al, 2009). However, our results support the majority of the published results linking TReg cells with favourable outcome in CRC (Salama et al, 2009; Frey et al, 2010), as high FoxP3+ T-cell count had the highest association with lower recurrences of all the individual cell markers and FoxP3+ T cells clustered along with other T cells in hierarchical clustering analysis. Nevertheless, the mechanisms accounting for the impact of TReg cells in CRC and for the inconsistencies in their roles in different cancers remain unclear.

Dendritic cells are important APCs responsible for the induction of adaptive immune responses (Banchereau et al, 2000). After capturing antigens, immature DCs mostly reside to lymph nodes to facilitate maturation and antigen presentation to T cells. The significance of local mature DCs in CRC immunity was originally described by Suzuki et al (2002), who found that mature DCs make small aggregates with T cells in the invasive margin of CRC to promote T-cell activation. In agreement with these findings, we found high numbers of mature DCs both intra- and peritumourally. This suggests that after antigen capture, some of the DCs reside to tumour stroma and mature, potentially contributing to T-cell activation in tumour stroma. This phenomenon is not unique to CRC but can also be observed in other malignancies, for example, in non-small-cell lung cancer (Dieu-Nosjean et al, 2008). In our study, CD1a+ immature DCs did not associate with stage and clustered far apart from other cells in hierarchical clustering, whereas CD83+ mature DCs had a strong association with lower stage and clustered along with CD3+ T cells. This result supports the importance of tumour-associated mature DCs in effective T-cell responses against the tumour and encourages further studies addressing different DC subgroups in CRC.

Tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) may contribute to antigen presentation and cancer cell phagocytosis (Mantovani et al, 2002), and accordingly, high TAM infiltration at the invasive front of CRC has been associated with improved survival (Klintrup et al, 2005; Forssell et al, 2007). However, TAMs polarised towards M2 phenotype may promote tumour growth by, for example, inducing cancer cell proliferation (by the secretion of growth factors), angiogenesis (by the secretion of vascular growth factors), and metastasis (by the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases) (Mantovani et al, 2002). Indeed, conversely to peritumoural TAMs, intratumoural TAMs have been linked with CRC progression (Kang et al, 2010), suggesting that TAM phenotypes may show differences in different tumour locations. Accordingly, in our analyses, intratumoural CD68+ TAMs did not associate with stage (P=0.629) or recurrence rate (P=0.619), whereas peritumoural CD68+ TAMs showed a trend towards lower cell densities in advancing stage (P=0.055) and in the presence of recurrences (P=0.080). These findings lend support to the importance of peritumoural TAMs in CRC defence irrespective of intratumoural TAMs. The potential alterations in TAM phenotypes depending on their distribution in the tumour will be the subject of future work, with reliable analyses requiring thorough validation of the methods used in their identification.

In addition to macrophages, the location of other tumour-associated inflammatory cell types may be important (Galon et al, 2006). Our analysis identified T lymphocytes as the most frequent of the studied cell types, both in the tumour core and at the invasive front. Relative to FoxP3+ TReg cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells were slightly more common at the invasive front compared with the intratumoural stroma, indicating a higher cytotoxic activity at the invasive front. Moreover, the infiltrate at the invasive front had universally (excluding mast cells) higher inverse correlation with stage than the intratumoural infiltrate. This underlines the importance of dense peritumoural inflammatory cell infiltration – comprising cells of both adaptive and innate immunity cells – in restricting tumour growth, supporting the relevance of the K–M classification. Indeed, the invasive front of CRC is the site of important events in tumour progression including epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Natalwala et al, 2008), and inflammatory reaction at the invasive front, specifically, has also earlier been proposed to be decisive for the clinical outcome of patients (Zlobec and Lugli, 2009).

Regardless of the short follow-up in our recurrence analysis, high CD3+ and FoxP3+ T-cell counts, in addition to high K–M score, significantly associated with lower recurrence rate. There is a need for standardisation of the evaluation of inflammatory cell infiltration in CRC to provide an effective prognostic and potentially predictive tool (Pages et al, 2010). Immunoscore consisting of the densities of CD3+ and CD8+ T cells represents a creditable attempt to incorporate immune cell infiltration into cancer classification (Galon et al, 2012), and our results here support the validity of CD3 and CD8 as markers of CRC immunity status. Immunoscore definitions and methods include accurate cell counts acquired with objective computer-based methods (Galon et al, 2012), which provide excellent reproducibility (Väyrynen et al, 2012b). However, the availability of computer-based immunohistochemistry analysis could hinder the introduction of Immunoscore, and at this point it is not known whether specific immunohistochemical markers would provide any additional information compared with the analysis of the inflammatory reaction from H&E slides (Roxburgh and McMillan, 2012).

Besides the T-cell subsets included in Immunoscore (Galon et al, 2012), K–M score has been shown to be reproducible and to harbour stage-independent prognostic value in several independent studies (Klintrup et al, 2005; Roxburgh et al, 2009a; Richards et al, 2012a). Therefore, K–M score has been cited as a rational point of comparison for the immunohistochemical inflammatory markers (Roxburgh and McMillan, 2012). Our present study provided important data on the contributions of individual cell types to K–M score and the interrelationships between different cell types, adding to the understanding of CRC-associated inflammatory reactions. However, the number of events and the time of observation limited our chances to firmly conclude the clinical impact of the components of immune cell infiltrate in CRC, and further investigation is also needed for a conclusive comparison of the prognostic value of K–M score relative to individual immunohistochemical inflammatory markers.

We utilised MLH1 and MSH2 immunohistochemistry for MSI screening, which has been attributed 92.3% sensitivity and 100% specificity in a large series of 1144 cases (Lindor et al, 2002). Relative to MLH1 and MSH2, an isolated loss in other MMR enzymes, MSH6 and PMS2, is infrequent in CRC, occurring in <10–15% of Lynch syndrome cases and hardly ever in sporadic cases (Peltomäki, 2001). In our data, intra- and peritumoural CD3+ and CD8+ T cells were the only cell types to show significant associations with loss of either MLH1 or MSH2. However, the densities of several other cell types were also higher in the absence of MLH1 or MSH2, but the number of MMR-deficient cases (n=11) was too small to enable definite conclusions.

In summary, the density of overall CRC inflammatory cell infiltrate declines as tumour stage advances, likely depicting weakening immune response against the tumour. Especially, low K–M score and low T-cell counts predict higher recurrence rate. There are high positive correlations between the constituents of CRC inflammatory infiltrate, supporting the value of general inflammatory scoring.

Change history

01 October 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int 11: 36–42.

Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K (2000) Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 18: 767–811.

Bates GJ, Fox SB, Han C, Leek RD, Garcia JF, Harris AL, Banham AH (2006) Quantification of regulatory T cells enables the identification of high-risk breast cancer patients and those at risk of late relapse. J Clin Oncol 24: 5373–5380.

Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M, Zhu Y, Wei S, Kryczek I, Daniel B, Gordon A, Myers L, Lackner A, Disis ML, Knutson KL, Chen L, Zou W (2004) Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med 10: 942–949.

Dieu-Nosjean MC, Antoine M, Danel C, Heudes D, Wislez M, Poulot V, Rabbe N, Laurans L, Tartour E, de Chaisemartin L, Lebecque S, Fridman WH, Cadranel J (2008) Long-term survival for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with intratumoral lymphoid structures. J Clin Oncol 26: 4410–4417.

Forssell J, Oberg A, Henriksson ML, Stenling R, Jung A, Palmqvist R (2007) High macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlates with improved survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13: 1472–1479.

Frey DM, Droeser RA, Viehl CT, Zlobec I, Lugli A, Zingg U, Oertli D, Kettelhack C, Terracciano L, Tornillo L (2010) High frequency of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells predicts improved survival in mismatch repair-proficient colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer 126: 2635–2643.

Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J (2012) The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer 12: 298–306.

Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F (2006) Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 313: 1960–1964.

Galon J, Pages F, Marincola FM, Angell HK, Thurin M, Lugli A, Zlobec I, Berger A, Bifulco C, Botti G, Tatangelo F, Britten CM, Kreiter S, Chouchane L, Delrio P, Arndt H, Asslaber M, Maio M, Masucci GV, Mihm M, Vidal-Vanaclocha F, Allison JP, Gnjatic S, Hakansson L, Huber C, Singh-Jasuja H, Ottensmeier C, Zwierzina H, Laghi L, Grizzi F, Ohashi PS, Shaw PA, Clarke BA, Wouters BG, Kawakami Y, Hazama S, Okuno K, Wang E, O’Donnell-Tormey J, Lagorce C, Pawelec G, Nishimura MI, Hawkins R, Lapointe R, Lundqvist A, Khleif SN, Ogino S, Gibbs P, Waring P, Sato N, Torigoe T, Itoh K, Patel PS, Shukla SN, Palmqvist R, Nagtegaal ID, Wang Y, D’Arrigo C, Kopetz S, Sinicrope FA, Trinchieri G, Gajewski TF, Ascierto PA, Fox BA (2012) Cancer classification using the Immunoscore: a worldwide task force. J Transl Med 10: 205–5876-10-205.

Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kudo S, Riboli E, Nakamura S, Hainaut P, Rubio CA, Sobin LH, Fogt F, Winawer SJ, Goldgar DE, Jass JR (2000) Carcinoma of the colon and rectum. In World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, (eds), pp 103–143. IARC Press: Lyon.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144: 646–674.

Jass JR (1986) Lymphocytic infiltration and survival in rectal cancer. J Clin Pathol 39: 585–589.

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ (2009) Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 59: 225–249.

Kang JC, Chen JS, Lee CH, Chang JJ, Shieh YS (2010) Intratumoral macrophage counts correlate with tumor progression in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 102: 242–248.

Kantola T, Klintrup K, Väyrynen JP, Vornanen J, Bloigu R, Karhu T, Herzig KH, Näpänkangas J, Mäkelä J, Karttunen TJ, Tuomisto A, Mäkinen MJ (2012) Stage-dependent alterations of the serum cytokine pattern in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 107 (10): 1729–1736.

Klintrup K, Mäkinen JM, Kauppila S, Väre PO, Melkko J, Tuominen H, Tuppurainen K, Mäkelä J, Karttunen TJ, Mäkinen MJ (2005) Inflammation and prognosis in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 41: 2645–2654.

Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Leontovich O, Goldberg RM, Cunningham JM, Sargent DJ, Walsh-Vockley C, Petersen GM, Walsh MD, Leggett BA, Young JP, Barker MA, Jass JR, Hopper J, Gallinger S, Bapat B, Redston M, Thibodeau SN (2002) Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing in phenotyping colorectal tumors. J Clin Oncol 20: 1043–1048.

Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A (2002) Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol 23: 549–555.

Nagtegaal ID, Marijnen CA, Kranenbarg EK, Mulder-Stapel A, Hermans J, van de Velde CJ, van Krieken JH (2001) Local and distant recurrences in rectal cancer patients are predicted by the nonspecific immune response; specific immune response has only a systemic effect—a histopathological and immunohistochemical study. BMC Cancer 1: 7.

Nagtegaal ID, Marijnen CA, Kranenbarg EK, Mulder-Stapel A, Hermans J, van de Velde CJ, van Krieken JH Pathology Review Committee (2002) Short-term preoperative radiotherapy interferes with the determination of pathological parameters in rectal cancer. J Pathol 197: 20–27.

Naito Y, Saito K, Shiiba K, Ohuchi A, Saigenji K, Nagura H, Ohtani H (1998) CD8+ T cells infiltrated within cancer cell nests as a prognostic factor in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 58: 3491–3494.

Natalwala A, Spychal R, Tselepis C (2008) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition mediated tumourigenesis in the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol 14: 3792–3797.

Nosho K, Baba Y, Tanaka N, Shima K, Hayashi M, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci E, Dranoff G, Fuchs CS, Ogino S (2010) Tumour-infiltrating T-cell subsets, molecular changes in colorectal cancer, and prognosis: cohort study and literature review. J Pathol 222: 350–366.

Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, Meyerhardt JA, Baba Y, Shima K, Glickman JN, Ferrone CR, Mino-Kenudson M, Tanaka N, Dranoff G, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS (2009) Lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer is associated with longer survival, independent of lymph node count, microsatellite instability, and CpG island methylator phenotype. Clin Cancer Res 15: 6412–6420.

Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, Mlecnik B, Kirilovsky A, Nilsson M, Damotte D, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Galon J (2005) Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 353: 2654–2666.

Pages F, Galon J, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Tartour E, Sautes-Fridman C, Fridman WH (2010) Immune infiltration in human tumors: a prognostic factor that should not be ignored. Oncogene 29: 1093–1102.

Peltomäki P (2001) Deficient DNA mismatch repair: a common etiologic factor for colon cancer. Hum Mol Genet 10: 735–740.

Richards CH, Flegg KM, Roxburgh CS, Going JJ, Mohammed Z, Horgan PG, McMillan DC (2012a) The relationships between cellular components of the peritumoural inflammatory response, clinicopathological characteristics and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 106: 2010–2015.

Richards CH, Roxburgh CS, Anderson JH, McKee RF, Foulis AK, Horgan PG, McMillan DC (2012b) Prognostic value of tumour necrosis and host inflammatory responses in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 99: 287–294.

Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC (2012) The role of the in situ local inflammatory response in predicting recurrence and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 38: 451–466.

Roxburgh CS, Salmond JM, Horgan PG, Oien KA, McMillan DC (2009a) Comparison of the prognostic value of inflammation-based pathologic and biochemical criteria in patients undergoing potentially curative resection for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 249: 788–793.

Roxburgh CS, Salmond JM, Horgan PG, Oien KA, McMillan DC (2009b) Tumour inflammatory infiltrate predicts survival following curative resection for node-negative colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 45: 2138–2145.

Salama P, Phillips M, Grieu F, Morris M, Zeps N, Joseph D, Platell C, Iacopetta B (2009) Tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T regulatory cells show strong prognostic significance in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 27: 186–192.

Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ (2011) Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 331: 1565–1570.

Sinicrope FA, Rego RL, Ansell SM, Knutson KL, Foster NR, Sargent DJ (2009) Intraepithelial effector (CD3+)/regulatory (FoxP3+) T-cell ratio predicts a clinical outcome of human colon carcinoma. Gastroenterology 137: 1270–1279.

Smyrk TC, Watson P, Kaul K, Lynch HT (2001) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are a marker for microsatellite instability in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 91: 2417–2422.

Sobin LH, Wittekind C (eds) (2002) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. Wiley-Liss: New York.

Suzuki A, Masuda A, Nagata H, Kameoka S, Kikawada Y, Yamakawa M, Kasajima T (2002) Mature dendritic cells make clusters with T cells in the invasive margin of colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol 196: 37–43.

Väyrynen JP, Vornanen J, Tervahartiala T, Sorsa T, Bloigu R, Salo T, Tuomisto A, Mäkinen MJ (2012a) Serum MMP-8 levels increase in colorectal cancer and correlate with disease course and inflammatory properties of primary tumors. Int J Cancer 131: E463–E474.

Väyrynen JP, Vornanen JO, Sajanti S, Böhm JP, Tuomisto A, Mäkinen MJ (2012b) An improved image analysis method for cell counting lends credibility to the prognostic significance of T cells in colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch 460: 455–465.

Zlobec I, Lugli A (2009) Invasive front of colorectal cancer: dynamic interface of pro-/anti-tumor factors. World J Gastroenterol 15: 5898–5906.

Zou W (2006) Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 6: 295–307.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Ms Riitta Vuento for her invaluable assistance in the preparation of the study material. This work was supported by grants from the Academy of Finland, Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finnish Cancer Foundation, Finnish Medical Foundation, Northern Finland Cancer Foundation, and Oulu University Scholarship Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Väyrynen, J., Tuomisto, A., Klintrup, K. et al. Detailed analysis of inflammatory cell infiltration in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 109, 1839–1847 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.508

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.508

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Developing a dual VEGF/PDL1 inhibitor based on high-affinity scFv heterodimers as an anti-cancer therapeutic strategy

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The Glasgow Microenvironment Score and risk and site of recurrence in TNM I–III colorectal cancer

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

-

The prognostic impact of the lymphocyte-to-C-reactive protein ratio in patients with unresectable or recurrent advanced gastric cancer treated with first- and second-line treatment

Surgery Today (2023)

-

A prognostic score based on B cell and plasma cell densities compared to T cell densities in colorectal cancer

International Journal of Colorectal Disease (2023)

-

Clinical implications of the preoperative lymphocyte C-reactive protein ratio in esophageal cancer patients

Surgery Today (2021)