Abstract

Ethnic disparities in use of cancer genetics services raise concerns about equitable opportunity to benefit from familial cancer risk assessment, improved survival and quality of life. This paper considers available research to explore what may hinder or facilitate minority ethnic access to cancer genetics services. We sought to inform service development for people of South Asian, African or Irish origin at risk of familial breast, ovarian, colorectal and prostate cancers in the UK. Relevant studies from the UK, North America and Australasia were identified from six electronic research databases. Current evidence is limited but suggests low awareness and understanding of familial cancer risk among minority ethnic communities studied. Socio-cultural variations in beliefs, notably stigma about cancer or inherited risk of cancer, are identified. These factors may affect seeking of advice from providers and disparities in referral. Achieving effective cross-cultural communication in the complex contexts of both cancer and genetics counselling, whether between individuals and providers, when mediated by third party interpreters, or within families, pose further challenges. Some promising experience of facilitating minority ethnic access has been gained by introduction of culturally sensitive provider and counselling initiatives, and by enabling patient self-referral. However, further research to inform and assess these interventions, and others that address the range of challenges identified for cancer genetics services are needed. This should be based on a more comprehensive understanding of what happens at differing points of access and interaction at community, cancer care and genetic service levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Cancer genetic services offer important opportunities to benefit from assessment of familial cancer risk, with further testing and screening where appropriate.1 Inherited mutations account for up to 10% of breast cancers, in particular BRCA1 and 2 (breast cancer, early onset),2 with 5% of ovarian cancer attributed to BRCA1 mutations.3 Up to 5% of prostate cancer, particularly that affecting younger men, occurs in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers,4 while a family history of hereditary prostate cancer confers a five to eleven fold increased risk.5 Some 3–5% of colorectal cancer is currently attributed to identified mutations, and the risk of developing associated cancer syndromes is high.6, 7 Existing interventions can improve survival and quality of life following targeted screening and early diagnosis in those identified at higher familial risk.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Cancer genetic assessment can also reduce psychological distress and improve knowledge of breast cancer, genetics and understanding of risk.13

Despite these benefits, people from minority ethnic communities appear poorly represented in genetics services. In particular, measurable ethnic disparities in use of genetic testing and counselling have been observed in cancer genetics.14, 15 It is possible that in the past this was partially due to lower cancer rates in family members both in the Western world and in the country of biological origin. However, disproportionately low minority uptake in genetic counselling has been observed when the family history of breast cancer is similar to that of the white population, for example, in the USA,14 and in Holland, where referrals were half of that expected given population demographics.16 Mutations in Mendelian cancer susceptibility genes have been detected in different ethnic groups at a similar frequency in a number of studies.17 Thus, the lower proportion of familial cancer susceptibility referrals for black and minority ethnic groups are unlikely to be due to differences in inherited familial cancer susceptibility.

Inequitable access across medical genetics services has raised international18 concerns to better understand how issues such as ethnicity may affect use of genetic services19 The wider socio-economic influences on ethnic variations in access to health care are well recognised.20 However, issues more specific to particular health-care contexts for minority communities should not be ignored,21 as these may be more amenable to being addressed by service improvement. We sought to inform the development of service interventions for people of South Asian, African or Irish origin at risk of familial breast/ovarian, colorectal and prostate cancers in the UK. As a first phase of informing future interventions, we aimed to identify and consider current evidence on what may facilitate or hinder minority ethnic access to cancer genetics services in English-speaking developed countries.

METHODS

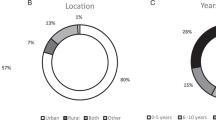

Relevant evidence was identified from six electronic sources from their inception to March 2012 (Embase; Medline; CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature); PsychINFO; Cochrane Reviews; Web of Knowledge/Web of Science). We combined terms relating to: access to health care, cancer genetics services, genetic testing and counselling, minority ethnic groups and common hereditary cancers. We sought primary quantitative and qualitative research studies involving adults aged 18–70 years of either gender, with or at risk of familial breast or ovarian, colorectal or prostate cancer; and who were of African descent, White Irish or South Asian origin (people born in, or descended from those born in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh or Sri Lanka). These are among the most common minority communities in the UK where evidence of poor access, particularly to secondary health care exists. We sought studies reported in English from North America, UK and Australasia, and included search of author citations from papers obtained and bibliographies of individual papers.

Titles and abstracts of 795 papers were reviewed (766 identified from search strategy and 29 through citation), resulting in identification of 21 potentially relevant papers at full text. These were reviewed independently by two researchers who agreed upon 11 studies containing data germane to our aim, comprising two entirely qualitative,22, 23 two mixed methods24, 25 and seven quantitative reports,1, 26, 27, 28 with four of the eleven studies involving service pilot interventions.22, 25, 29, 30 These are summarised in Table 1. Study reports and data were examined by three researchers. While published evidence was modest, with several limitations (Table 1), it was possible to identify insights and themes from qualitative studies based on a thematic network approach, exploring and categorising findings across studies in order to integrate these into global themes.31 Existing quantitative data were limited and heterogeneous and were used to triangulate and identify relevance of themes where possible, rather than to quantify the outcomes. A lack of primary qualitative data presented in most reports militated against possibilities for substantive meta-synthesis.32 Common themes were thus developed into a descriptive narrative for this paper.33

Results

Barriers and facilitators to minority ethnic access to cancer genetics services were identified within four broad themes developed from study data: cultural variations in beliefs about cancer and inheritance; awareness of risk and accessing assessment; cross-cultural communication and facilitating engagement and uptake.

Cultural variation in beliefs about cancer and inheritance

Cultural variation in beliefs about cancer and inheritance offered potential barriers to accessing cancer genetics assessment. For example, stigma from a cancer diagnosis or from the notion of being at risk of familial cancer was found in studies involving South Asian and African origin communities.24, 25, 27, 29 Atkin et al,22 evaluating access to a genetics service pilot, highlight taboos about cancer among South Asian communities including refraining from using the word ‘cancer’. South Asians had less knowledge of cancer than the white majority, believed cancer to be a condition affecting white women and could equate cancer with death, as did some African Americans.23, 24

Fatalistic views that nothing could be done if one developed cancer because of a family history of cancer were found among some South Asians22 and some African Americans, which led to the avoidance of screening.24 Similarly, Ford et al34 found African Americans who had a more fatalistic view about their risk of breast cancer were unwilling to receive genetic counselling. Familial interdependence (not thinking of oneself as separate from family) was also associated with African American women having a more negative attitude towards genetic counselling and testing.

On the other hand, religious faith in opportunities such as cancer screening and genetic counselling appeared to motivate some African American women to engage in assessment for familial cancer risk,23 or be more positive toward genetic risk assessment and counselling, and about the value of information about genetic cancer risk.34

Awareness of familial cancer risk and accessing assessment

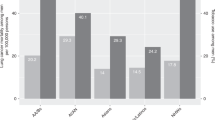

Minority ethnic representation in cancer genetics services was identified to remain at ∼2.5–3% in the UK during the past decade1, 26 including within localities of high African-Caribbean30 or South Asian density,28 although minority ethnic communities have risen to 14% of the UK population in the same period.35

Interest in breast cancer genetic counselling was identified in people of African American, Native American and European American ethnicities in one US city,28 but people from ethnic minority groups appeared largely unaware of genetic cancer services, for example in the UK.22, 30 Other barriers to access were identified, for example, African Americans at higher breast cancer risk not wanting genetic counselling feared a cancer diagnosis.23 Anticipation of negative emotions was related to avoidance of genetic testing24 in addition to concerns about confidentiality among women of African descent who had less education and income than US-born women.27 Similarly, Culver et al28 found interest in, and acceptance of, free breast cancer genetic risk assessment was greatest in more educated women with a family history of breast cancer and relatively less among African Americans with lower educational opportunity or attainment.

Concern about personal risk and awareness of family history appeared drivers for referral and interest in genetic assessment among the general population,26 with studies suggesting much may thus rely on initiation by the patient.22, 25, 26 Atkin et al22 found that patients concerned about family history of cancer expected primary care providers to provide information about cancer genetics risk assessment but related referral was found to vary significantly.26, 30 Many referrals not only occurred for people at lower risk for common familial cancers1, 26 but were more likely to be for white patients.22 Variation in use of family history questionnaires, for triage prior to genetic cancer risk assessment, appeared a further potential barrier to accessing cancer genetics services.1 Indeed, one study found some patients may be confused about why providing family history information may yield risk estimation for certain cancers.22

Encouraging patient self-referral showed some promise25, 30 with cancer genetic risk being assessed as no higher in patients referred by physicians compared with patients who self-referred.25 However, communication appeared to remain an enduring challenge for access, including practical issues such as sharing the same language when making appointments by telephone.25, 30 Moreover, language barriers at the point of taking a family history may have resulted in failure to identify a significant history of familial cancer.29

Cross-cultural communication

In the context of cancer genetics, people of South Asian origin have reported feeling some service interpreters were making decisions on their behalf, or selectively choosing what information to translate to them. Use of family members as interpreters who themselves may be at increased familial cancer risk was also stressful for people and no less problematic.22

Despite advantages for access of seeing genetics practitioners with bilingual skills in pilot community clinics,29 people of South Asian origin still experienced uncertainty, feeling information they were given was too vague. They felt consultations were too professional-centred and focused on the collection of information rather than explaining why this might be useful.22 Additionally, South Asians preferred more direct explanations and advice about risk and interventions that would have enabled them to discuss the issue more readily with relatives, rather than concentrating on provision of information about their probability of developing cancer.22

After cancer genetic counselling, some African American women found that greater knowledge and education about their personal breast cancer risk was reassuring and were positive about enhancing vigilance through breast cancer screening, though worry about being diagnosed with breast cancer increased.23 However, others at increased risk of breast cancer doubted the value of the information they had received if it did not prevent cancer, and did not perceive the importance of paternal health history.23 Moreover, mistrust of how their health information would be used was identified as a barrier for African American women having cancer genetic counselling with health care professionals who were not known to them.23

Considering communication with wider family there was unwillingness to discuss cancer even in families with a strong family history among African Americans, possibly associated with uncertainty about the usefulness of preventive or treatment options.24 People of South Asian origin reported reluctance to communicate a cancer diagnosis due not only to stigma, but also when communication between women and men may be considered culturally inappropriate.22 In this context, some also had concerns about health professionals being focused on their confidentiality as individual patients, rather than assisting them with the challenges of conveying information about familial cancer risk to family members.

Facilitating engagement and uptake

Some relatively positive experience has arisen from several pilot cancer genetics service developments.25, 29, 30 Examples included talks at faith centres, cultural events, use of local newspapers and radio and a service linked website supported by translated leaflets to raise awareness of familial cancer, in addition to making services community located.25, 28, 30 While these approaches appeared acceptable to target communities, they alone have not been associated with significant increase in minority ethnic engagement or service uptake.29

However, encouraging patient self-referral has shown some promise in enhancing uptake,25, 30 alongside use of self-triage questions about risk,30 and considering flexibility in clinic times.25, 29, 30 In particular, deploying providers with cultural and linguistic backgrounds shared with target populations can improve satisfaction with cancer genetic services and be helpful in reducing religious sensitivities when communicating bad news, for example in some South Asian communities.22, 29

Closer collaboration between cancer genetics services, primary care and cancer care providers, tailored to local populations may also improve access. This has included placing services in the local community together with enhanced training and awareness of familial cancer risk for health-care professionals,25, 29, 30 including identification of patients at familial cancer risk by primary care clinicians.25 One community-based pilot service, seeing self-referred patients and supported by dedicated interpreting for patients, used shared computerised pedigree software to seamlessly transfer information to a regional genetics service if patients then needed further specialist assessment.30

DISCUSSION

The available research suggests minority ethnic access to cancer genetics assessment may be hindered by low community awareness and understanding of familial cancer risk, and socio-cultural variations in beliefs, notably stigma about cancer or inherited risk of cancer. These factors may affect seeking of advice from providers and contribute to disparities in referral. Cross-cultural communication between individuals and providers, including when mediated by third-party interpreters, or communication within families, in the complex contexts of cancer and genetic counselling, pose several further challenges. Some promising experience of facilitating access has been gained by introduction of culturally sensitive provider and counselling interventions in cancer genetics service developments, and by enabling patient self-referral.

Strengths and limitations

Up until a decade ago, empirical work in this field largely concerned African Americans.36 The research now considered here has grown to include a wider range of minority ethnic communities, including those from Asian backgrounds and from outside North America. This provides useful information to inform future intervention development and research, but the relative paucity and limitations of available evidence should still be recognised. Themes presented in this paper must be interpreted with regard to the particular study contexts and the minority communities of concern, as described and reported within them. We found qualitative studies offered helpful insights into what may shape access. However, with some exceptions,22 there were little primary data on direct patient experience presented in reports, militating against possibilities for substantive meta-synthesis.32 Data available from quantitative studies were limited and heterogeneous, mostly from observational surveys, with small or convenience samples limiting generalisability, and could not be pooled.

Relation to other work

People’s understanding of genetics,37, 38 knowledge of cancer and terms used,39 and inherited cancer40 has been recognised to be generally low among diverse ethnic populations. Cultural variations in perceptions of which relatives constitute close family members have been identified, for example among Chinese Australians,41 underlining how patterns of inheritance for disease may be variably understood, and consistent with the confusion about this noted here.23 Other evidence also suggests differing kinship systems may affect the way people view inheritance, and thus genetic counselling, because of family privacy,36, 42 or highlights cultural differences in people’s advice seeking about cancer.43

Concerns about how genetic cancer risk information might be used by health providers has also been identified elsewhere among African Americans.37 Other experience lends further support to the prospect that access to genetics cancer services may be enhanced by cultural adaptations, including, for example, development of communication aids44 or culturally tailored genetic counselling for Latinas or Maori people.45, 46

Implications for intervention development and research

Cancer rates in South Asia are rising47 and will increase the proportion of migrant patients in the Western world having a significant family history, who may then be eligible for a referral to a familial cancer susceptibility clinic. In addition, while the prevalence of cancers among immigrant minority communities in many developed countries has been low, it is increasing with greater exposure to Western lifestyle risks,48 including growth in obesity,49 with growing evidence cancer rates are increasing for the same population (http://www.ncin.org.uk/view?rid=2223). Yet referral patterns to cancer genetics services have changed little.50 The issue of familial risk may commonly be initiated by individuals presenting concern to their primary care providers, particularly among those who are asymptomatic and white.51 Combinations of less community knowledge or experience of cancer, stigma and sometimes lower educational opportunity may mean individuals from minority ethnic communities remain less aware of the potential relevance to their health of family history or risk of cancer. They may be reluctant or less empowered to seek information or advice from providers. These delays in presentation are often compounded by the need for a higher number of primary care practitioner appointments prior to a referral for potential cancer diagnostic investigations.52 These barriers may combine resulting in a later diagnosis with consequences for treatment.53

The current evidence underlines need for interventions that involve proactive provision of familial cancer risk information and assessment opportunities, and evaluation of their clinical and cost-effectiveness. Communities in more socially deprived settings might form a particular priority. This could include community awareness raising, use of outreach and patient self-referral, building on the promise of emerging culturally adapted service and nurse led models.22, 25, 30 The advantages of closer integration between ‘non-specialist’ primary or cancer care providers and specialist genetics services should be exploited.1, 25, 29, 30 This should include systematic ethnicity monitoring to assist not only audit of access but also tracking of tumour incidence and survival among minority communities.1, 54 Parallel priorities are specific training of both interpreters and health providers in achieving successful triadic cross-cultural communication, recognising the particular challenges of doing so when discussing not only cancer55 but also the complexities of inheritance, genetic risk, testing and screening.

Access to appropriate assessment may also be shaped by professionals’ awareness of familial cancer risk. Providers in primary care56 and the range of physicians or surgeons in cancer care57 may feel they lack adequate genetic knowledge or skills in this area. This, and challenges of communication, including language barriers, may be one reason those from ethnic minorities appear less likely to be referred to cancer genetics services. Interventions should consider how providers might be better supported to initiate familial cancer risk assessment and genetics referral.

For cancer genetics providers, exploration of approaches that reduce barriers at initial stages of triaging risk, and targeting of culturally sensitive support for individuals to better understand their risk and options are needed. This should include facilitating communication of relevant information within families, given the cultural reluctance24 and stigma that may pose barriers to doing so found in the current studies22, 23, 27, 29 and elsewhere.58

Given the relative lack of research, greater understanding of the perspectives of minority ethnic people at familial cancer risk, those experiencing cancer genetics services and the range of providers involved is still needed to refine our knowledge of what shapes, and may enhance access and outcomes. This should include identifying learning from studies in other service settings, including those in non-English-speaking countries not included in this paper. Further qualitative research, including direct observation of encounters, could inform and assess the range of service development approaches suggested, prior to their further evaluation in experimental designs. In particular, a more comprehensive understanding of what happens at the differing points of access and interaction across the care pathway is required at community, cancer care and genetic service levels. The challenges for achieving more equitable and effective cancer genetics care remain considerable, but tackling them will be vital to benefit growing proportions of our populations.

References

Wonderling D, Hopwood P, Cull A et al: Descriptive study of UK cancer genetics services: an emerging clinical response to the new genetics. Br J Cancer 2001; 85: 166–170.

McPherson K, Steel CM, Dixon JM : Breast cancer: epidemiology, risk factors and genetics. Br Med J 2009; 321: 624–628.

Stratton JF, Thompson D, Bobrow L et al: The genetic epidemiology of early-onset epithelial ovarian cancer: a population-based study. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65: 1725–1732.

Kote-Jarai Z, Leongamornlert D, Saunders E et al: BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 1230–1234.

Bratt O : Hereditary prostate cancer: clinical aspects. J Urol 2002; 168: 906–913.

Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ et al: Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2009; 59: 666–690.

Balmana J, Castells A, Cervantes A : Familial colorectal cancer risk: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 78–81.

FH01 collaborative teams: Mammographic surveillance in women younger than 50 years who have a family history of breast cancer: tumour characteristics and projected effect on mortality in the prospective, single-arm, FH01 study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 1127–1134.

Leach MO, Boggis CR, Dixon AK et al: Screening with magnetic resonance imaging and mammography of a UK population at high familial risk of breast cancer: a prospective multicentre cohort study (MARIBS). Lancet 2005; 365: 1769–1778.

Kriege M, Brekelmans CT, Boetes C et al: Efficacy of MRI and mammography for breast-cancer screening in women with a familial or genetic predisposition. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 427–437.

Järvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H et al: Controlled 15-year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2000; 118: 829.

de Jong AE, Hendriks YM, Kleibeuker JH et al: Decrease in mortality in Lynch syndrome families because of surveillance. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 665–671.

Hilgart JS, Coles B, Iredale R : Cancer genetic risk assessment for individuals at risk of familial breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 2: CD003721.

Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M : Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. JAMA 2005; 293: 1729–1736.

Pagán JA, Su D, Li L, Armstrong K, Asch DA : Racial and ethnic disparities in awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk. Am J Prev Med 2009; 37: 524–530.

van Riel E, van Dulmen S, Ausems MG : Who is being referred to cancer genetic counseling? Characteristics of counselees and their referral. J Commun Genet 2012; 3: 265–274.

Hall MJ, Reid JE, Burbidge LA et al: BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in women of different ethnicities undergoing testing for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. Cancer 2009; 115: 2222–2233.

Godard B, Kaariainen H, Kristoffersson U, Tranebjaerg L, Domenico Coviello D, Aymé S : Provision of genetic services in Europe: current practices and issues. Eur J Hum Genet 2003; 11 (Suppl 2): S13–S48.

US Department of Health and Human Services: Coverage and Reimbursement of Genetics Tests and Services. Washington, USA, 2006, http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/sacghs/reports/CR_report.pdf . Accessed 9 April 2013..

US Department of Health and Human Services: Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black & Minority Health, Volume I: Executive Summary 1985, http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/checked/1/ANDERSON.pdf . Accessed 9 April 2013..

Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E : Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev 2000; 57 (Suppl 1): 108–145.

Atkin K, Ali N, Chu CE : The politics of difference? Providing a cancer genetics service in a culturally and linguistically diverse society. Divers Health Care 2009; 6: 149–157.

Ford ME, Alford SH, Britton D, McClary B, Gordon HS : Factors influencing perceptions of breast cancer genetic counseling among women in an urban health care service. J Genet Couns 2007; 16: 735–753.

Matthews AK, Cummings S, Thompson S, Wohl V, List M, Olopade OI : Genetic testing of African Americans for susceptibility to inherited cancers. J Psychosoc Oncol 2000; 18: 1–19.

Gulzar Z, Goff S, Njindou A et al: Nurse-led cancer genetics clinics in primary and secondary care in varied ethnic population areas: interaction with primary care to improve ascertainment of individuals from ethnic minorities. Fam Cancer 2007; 6: 205–212.

Fraser L, Bramald S, Chapman C et al: What motivates interest in attending a familial cancer genetics clinic? Fam Cancer 2003; 2: 159–168.

Sussner KM, Thompson HS, Jandorf L et al: The influence of acculturation and breast cancer-specific distress on perceived barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer among women of African descent. Psychooncol 2009; 18: 945–955.

Culver J, Burke W, Yasui Y, Durfy S, Press N : Participation in breast cancer genetic counseling: the influence of educational level, ethnic background, and risk perception. J Genet Couns 2001; 10: 215–231.

Srinivasa J, Rowett E, Dharni N, Bhatt H, Day M, Chu CE : Improving access to cancer genetics services in primary care: socio-economic data from North Kirklees. Fam Cancer 2007; 6: 197–203.

Jacobs C, Rawson R, Campion C et al: Providing a community-based cancer risk assessment service for a socially and ethnically diverse population. Fam Cancer 2007; 6: 189–195.

Attride-Sterling J : Thematic networks: an analytical tool for qualitative research. Qualit Res 2001; 1: 385–405.

Mays N, Pope C, Popay J : Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005; 10: 6–20.

ope C, Mays N, Popay J : Synthesizing Qualitative and Quantitative Health Evidence. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press, 2007.

Hughes C, Fasaye G-A, LaSalle VH, Finch C : Sociocultural influences on participation in genetic risk assessment and testing among African American women. Patient Educ Couns 2003; 51: 107–114.

Census: Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales. London, UK: Office for National Statistics, 2011, http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_290558.pdf . Accessed 4 February 2013..

Meiser B, Eisenbruch M, Barlow-Stewart K, Tucker K, Steel Z, Goldstein D : Cultural aspects of cancer genetics: setting a research agenda. J Med Genet 2001; 38: 425–429.

Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Benkendorf J et al: Ethnic differences in knowledge and attitudes about BRCA1 testing in women at increased risk. Patient Educ Couns 1997; 32: 51–62.

Shaw A, Hurst JA : ‘What is this genetics, anyway?’ Understandings of genetics, illness causality and inheritance among British Pakistani users of genetic services. J Genet Couns 2008; 17: 373–383.

Shokar NK, Vernon SW, Weller SC : Cancer and Colorectal Cancer: Knowledge, Beliefs, and Screening Preferences of a Diverse Patient Population. Fam Med 2005; 37: 342–347.

Donovan KA, Tucker DC : Knowledge About Genetic Risk for Breast Cancer and Perceptions of Genetic Testing in a Sociodemographically Diverse Sample. J Behav Med 2000; 23: 15–36.

Eisenbruch M, Yeo SS, Meiser B, Goldstein D, Tucker K, Barlow-Stewart K : Optimising clinical practice in cancer genetics with cultural competence: lessons to be learned from ethnographic research with Chinese-Australians. Soc Sci Med 2004; 59: 235–248.

Saleh M, Barlow-Stewart K, Meiser B, Muchamore I : Challenges faced by genetics service providers’ practicing in a culturally and linguistically diverse population: an Australian experience. J Genet Couns 2009; 18: 436–446.

Scanlon K, Harding S, Hunt K, Petticrew M, Rosato M, Williams R : Potential barriers to prevention of cancers and to early cancer detection among Irish people living in Britain: a qualitative study. Ethnic Health 2006; 11: 325–341.

Baty BJ, Kinney AY, Ellis SM : Developing culturally sensitive cancer genetics communication aids for African Americans. Am J Med Genet 2003; 118A: 146–155.

Ricker C, Lagos V, Feldman N et al: If we build it...will they come? - Establishing a cancer genetics services clinic for an underserved predominantly Latina cohort. J Genet Couns 2006; 15: 505–513.

Port RV, Arnold J, Kerr D, Gravish N, Winship I : Cultural enhancement of a clinical service to meet the needs of indigenous people; genetic service development in response to issues for New Zealand Maori. Clin Genet 2008; 73: 132–138.

Takiar R, Nadayil D, Nandakumar A : Projections of number of cancer cases in India (2010-2020) by cancer groups. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2010; 11: 1045–1049.

Rastogi T, Devesa S, Mangtani P et al: Cancer incidence rates among South Asians in four geographic regions: India, Singapore, UK and US. Int J Epidemiol 2008; 37: 147–160.

Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F et al: Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 2013; 8: e53916.

Featherstone C, Colley A, Tucker K, Kirk J, Barton MB : Estimating the referral rate for cancer genetic assessment from a systematic review of the evidence. Br J Cancer 2007; 96: 391–398.

Al-Habsi H, Lim JNW, Chu CE, Hewison J : Factors influencing the referrals in primary care of asymptomatic patients with a family history of cancer. Genet Med 2008; 10: 751–757.

Lyratzopoulos G, Neal RD, Barbiere JM, Rubin GP, Abel GA : Variation in number of general practitioner consultations before hospital referral for cancer: findings from the 2010 National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in England. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 353–365.

Norwood MG, Mann CD, Hemingway D, Miller AS : Colorectal cancer: presentation and outcome in British South Asians. Colorectal Dis 2009; 11: 745–749.

Meade N, Genetic Interest GroupEthnic Monitoring in Clinical Genetics 2008, www.geneticalliance.org.uk/ethnicmonitoringreport_2008.pdf . Accessed 25 June 2010..

Kai J, Beavan J, Faull C : Challenges of mediated communication, disclosure and patient autonomy in cross-cultural cancer care. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 918–924.

Bethea J, Qureshi N, Drury N, Guilbert P : The impact of genetic outreach education and support to primary care on practitioner's confidence and competence in dealing with familial cancers. Community Genet 2008; 11: 289–294.

Powell CB, Littell R, Hoodfar E, Sinclair F, Pressman A : Does the diagnosis of breast or ovarian cancer trigger referral to genetic counseling? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013; 23: 431–436.

Benowitz S : To tell the truth: a cancer diagnosis in other cultures is often a family affair. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 1918–1919.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a UK Big Lottery Fund grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Author Contributions

AA led searches and screening of papers; CL assisted screening; AA, NQ and JK interpreted study reports and data; JB and NQ supported wider review and critical revisions; AA and JK wrote the paper; JK was principal investigator.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Allford, A., Qureshi, N., Barwell, J. et al. What hinders minority ethnic access to cancer genetics services and what may help?. Eur J Hum Genet 22, 866–874 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2013.257

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2013.257

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The role of virtual consultations in cancer genetics: challenges and opportunities introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic

BJC Reports (2023)

-

Investigating disparity in access to Australian clinical genetic health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Disparities in germline testing among racial minorities with prostate cancer

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2022)

-

Understanding genomic health information: how to meet the needs of the culturally and linguistically diverse community—a mixed methods study

Journal of Community Genetics (2021)

-

A Narrative Review of Implementing Precision Oncology in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer in Emerging Countries

Oncology and Therapy (2021)