Abstract

Difficult-to-control arterial hypertension is a common medical problem that may result from severe hypertensive disease or from poor adherence to the recommended medical treatment. The identification of non-adherent patients is challenging, especially when non-adherence is intentional. The current report describes the use of serum levels of prescribed antihypertensive drugs to evaluate the adherence in individuals with difficult-to-control arterial hypertension. Serum drug levels (SDLs) were evaluated by liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry. The chromatographic separation was performed on a reversed-phase column with a gradient flow of the mobile phase. The detection of analyzed substances was accomplished on a linear ion-trap mass spectrometer. The subjects were labeled as non-adherent when the serum level of at least one of the evaluated drugs was below the limit of quantification. The study used data from 84 patients with arterial hypertension who underwent SDL assessment to verify compliance with the recommended treatment. Patients who presented with uncontrolled blood pressure despite the recommended combination of at least three antihypertensives were enrolled in the analysis. Based on the evaluation of the SDLs, all of the evaluated drugs were found in the sera of 29 (34.5%) of the study patients. In the remaining 55 (65.5%) patients, non-adherence was diagnosed. None of the prescribed antihypertensive drugs was detected in the sera of the 29 (34.5%) patients. Our data suggest that an assessment of SDLs might be helpful before an extensive evaluation is initiated for difficult-to-control hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Difficult-to-control arterial hypertension is a relatively common and serious medical problem because the related cardiovascular risks are high. The management of patients with difficult-to-control arterial hypertension traditionally depends upon the identification of secondary forms of arterial hypertension and the selection of an appropriate treatment strategy. Although the disease-specific approach might be helpful in some patients with secondary forms of arterial hypertension, the combination of antihypertensive medications given in adequate doses is the keystone of treatment in the remaining cases. Difficult-to-control arterial hypertension may not, however, result solely from severe hypertensive disease itself, but from poor adherence to the recommended medical treatment.1

The identification of non-adherence can be challenging. Several methods to monitor the adherence exist, but none can be considered a gold standard.2 The consumption of prescribed drugs can be monitored by pill counts, rates of prescription refills and electronic medication monitors. The latter technique is currently considered the most accurate,3, 4, 5 but its widespread use in the daily clinical routine is hindered by high costs.

Monitoring techniques definitely have high specificity in the detection of non-adherence, but their sensitivity might be lower. None of the aforementioned methods is able to document that the prescribed drugs were actually ingested,6 which limits the identification of intentional non-adherence.

In common clinical practice, non-adherence to the prescribed antihypertensive medication can be deduced from indirect findings such as tachycardia despite an effective dose of β-blockers or a steadily elevated serum cholesterol level when a statin is prescribed. These suggestive clues, however, are usually not sufficient to label the patient as non-adherent. The only convincing evidence of non-adherence is an excessive reduction of blood pressure following the supervised ingestion of a single dose of a chronically recommended antihypertensive therapy. This test can be performed anywhere, provided the incidental hypotension can be effectively managed. According to our experience, however, this approach enables the identification of only a minor portion of non-compliant individuals.

As non-adherence to the recommended medical treatment has many potential consequences (for example medical, economical and legal consequences), we looked for another method to reliably verify non-adherence. In this report, we describe the evaluation of serum levels of prescribed antihypertensive drugs in individuals with difficult-to-control arterial hypertension.

Methods

Subjects and design

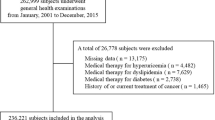

We performed a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients with difficult-to-control arterial hypertension who had serum drug levels (SDLs) measured because of suspected non-adherence to the recommended medical therapy.

The principal inclusion criterion was a history of difficult-to-control arterial hypertension defined by a repeatedly documented blood pressure elevation despite the recommended antihypertensive therapy consisting of a combination of at least three antihypertensives from different classes. In our hypertension clinic, blood pressure was measured in accordance with the current recommendations.7, 8

To avoid doubts regarding the presence of uncontrolled hypertension, the blood pressure inclusion criterion was set at 10/5 mm Hg above the arbitrary definition for arterial hypertension, that is, ⩾150/95 mm Hg. As the white-coat phenomenon can lead to an impression of difficult-to-control hypertension, most of the enrolled patients underwent ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Home blood pressure monitoring was accepted in patients for whom ambulatory monitoring was not feasible.

Patient adherence was normally questioned after the need for an extensive combination of antihypertensives and/or non-responsiveness to increased hypotensive medications.

Before the decision regarding SDL evaluation was made, the patients were specifically asked about the ingestion of antihypertensive drugs the evening before and the morning of the visit. If the answer was affirmative, the serum sample obtained during routine sampling was used for measurement of SDL. Given that the evaluation of SDL was considered a part of a routine clinical examination in our hospital, ethics committee approval was not required.

The determination of SDL

The determination of SDL was performed by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry.9, 10 Prior to the chromatographic separation, the serum samples were prepared by liquid–liquid extraction using a mixture of ethyl acetate and dichloromethane. The chromatographic separation was performed on a reversed-phase column with a gradient flow of the mobile phase (0.05 M formic acid and acetonitrile). The detection of the analyzed substances was accomplished on a linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (LTQ XL, Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) using electrospray ionization. The parameters of the mass spectrometer were adjusted for each individual analyte (antihypertensive drug). Pooled blank sera from healthy volunteers were used for method optimization and validation. Blank serum samples enriched with defined amounts of determined substances were used for calibration of the analytic method.

Using this precise and sensitive technique, we were able to measure the serum concentrations of betaxolol, metoprolol, bisoprolol, amlodipine, nitrendipine, verapamil, losartan, telmisartan, hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, furosemide, doxazosin, rilmenidine and urapidil. In each patient in whom SDL was evaluated, the liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry analysis was focused primarily on the prescribed antihypertensive drugs; the serum concentrations of other medications were not systematically evaluated.

Given that the clinical interpretation of serum concentrations of antihypertensive drugs is difficult, any quantifiable amount of the evaluated drug was interpreted to mean that the drug was taken. Only patients in whom the serum level of at least one drug was below the limit of quantification were labeled as non-adherent. By applying this criterion for non-adherence, we eliminated uncertainties and ethical bias from the interpretation of low concentrations of antihypertensives in the serum.

Statistical analysis

MedCalc (version 9) software was used for the statistical analysis of the acquired data. The patient characteristics were described by parametric statistics, and the differences between adherent and non-adherent patients were analyzed by Student's t-tests.

Results

The data of outpatients examined at our hypertension clinic between July 2007 and January 2010 were screened for this study. A total of 522 patient records were screened, and 84 individuals fulfilled the entry criteria and were enrolled in the analysis. All of the participants were Caucasian. The principal characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1. The recommended antihypertensive medications are summarized in Table 2.

For each patient enrolled, measurement of the SDL was possible for an average of 3.1 (±1.1) out of 5 (±1.2) drugs prescribed for the treatment of arterial hypertension. Fixed drug combinations (containing two drugs) were used in only three patients. For the purpose of the analysis, the patients were listed as taking these drugs separately.

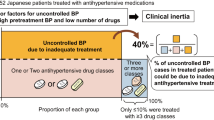

Of the 84 patients, 29 (34.5%) were deemed compliant because all drugs that were evaluated were found in the sera of these individuals. In the remaining 55 (65.5%) patients, the criteria for non-adherence were fulfilled. None of the evaluated drugs were detectable in 29 patients (34.5% of the study group). The prescribed antihypertensive medication had no significant effect on the observed non-adherence.

Surprisingly, in the sera of seven (8.3%) patients, we identified antihypertensive medications that were neither prescribed nor reported to be used by the patients. The comparison of compliant and non-compliant patients is shown in Table 3.

Discussion

We performed a study to verify drug adherence in patients who presented with difficult-to-control arterial hypertension. The observed rate of non-adherence did not differ significantly from other reports that used different techniques to assess the adherence.11, 12, 13 Compared with other approaches, however, the evaluation of SDL provides a reliable method to assess the actual adherence to the recommended therapy.

The measurement of SDL is not a novel method to test adherence to medical therapies.14, 15, 16 To the best of our knowledge, however, a similar approach has not been described in patients with difficult-to-control arterial hypertension.

Although costly and technically demanding, liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry enabled us to accurately identify a significant number of non-compliant patients among those who presented with uncontrollable hypertension. Given that liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry is currently considered to be the reference analytical technique,17 the observed non-compliance rate in our study group was unlikely to be an overestimate.

In fact, we have three main reasons to assume that the non-adherence rate among the study patients might have been underestimated. First, we were not able to analyze all prescribed antihypertensive medications. Second, our criteria for adherence were not sufficiently strict to identify patients taking the drugs irregularly or in lower doses. As mentioned above, any measurable amount of prescribed antihypertensive medication was interpreted in favor of the patient, that is, as if the patient was taking the drug as prescribed. Third, the SDL is naturally unable to detect white-coat adherence, that is, to identify those patients who took their medication only before the scheduled visits.

We can only speculate about the reasons for the observed non-adherence in our study group. Factors of non-adherence can be categorized into three groups: socioeconomic, motivational and communication related.18 In our opinion, the socioeconomic factors did not have a significant role. The health care system in our country enables the unlimited prescription of antihypertensive medications at negligible costs for those with very low incomes.

The most frequent reason for non-adherence was probably a lack of motivation arising from the fact that arterial hypertension is an oligosymptomatic disorder that requires long-lasting medical therapy. However, non-compliance was also demonstrated in those who had a history of intracranial hemorrhage, pulmonary edema or myocardial infarction.

The observed non-compliance could also be attributed to communication problems, reflecting a lack of trust in the relationship between patients and their physicians. The reasons for this impaired confidence are frequently unclear and difficult to accurately analyze. We can only speculate that disregard for or underestimation of drug-related side effects might contribute to this serious communication problem.

During the first visit to our hypertension clinic, the importance of mutual trust and compliance is stressed and broadly discussed with every new patient. Despite this, we still observe a significant number of non-compliant patients among those who present with uncontrollable hypertension. The motivation for non-compliance is clear only in those who aspire to receive disability benefits; in the remaining cases, we face an enormous and often perplexing communication barrier. Despite a specific approach based on frequent visits and intensive communication, non-adherence to the recommended treatment persists in many patients.

The magnitude of the difficulty in communication is supported by the fact that, in the sera of 7 out of 84 study patients, we found antihypertensives that were neither prescribed nor reported to be taken. The number of ‘self-prescribed’ drugs might have actually been even higher because the sera of the study patients were not systematically screened for the presence of all available antihypertensive drugs. Contrary to drug-related communication problems, only a negligible number of non-compliant patients seemed to be unaware of the risks related to elevated blood pressure.

Non-compliance is not a problem related only to antihypertensive medications.19, 20 In some non-compliant patients in our study, the uncontrollable hypertension was associated with resistance to warfarin, difficult-to-treat bronchial asthma and sideropenic anemia non-responsive to oral iron supplementation. Our data, however, cannot be automatically applied to other disorders that do not respond to chronic medical therapy.

It is also not clear to what extent our observations are applicable in other countries that have health and social care systems different from those in the Czech Republic.

Our data suggest that a SDL assessment might be helpful before an extensive evaluation for difficult-to-control hypertension is initiated. Using this approach, futile diagnostic procedures and therapeutic attempts can be avoided.

References

Burnier M, Schneider MP, Chiolero A, Stubi CL, Brunner HR . Electronic compliance monitoring in resistant hypertension: the basis for rational therapeutic decisions. J Hypertens 2001; 19: 335–341.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T . Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 487–497.

Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL . How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA 1989; 261: 3273–3277.

Farmer KC . Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 1999; 21: 1074–1090.

Zeller A, Schroeder K, Peters TJ . Electronic pillboxes (MEMS) to assess the relationship between medication adherence and blood pressure control in primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2007; 25: 202–207.

van Onzenoort HA, Verberk WJ, Kessels AG, Kroon AA, Neef C, van der Kuy PH, de Leeuw PW . Assessing medication adherence simultaneously by electronic monitoring and pill count in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2010; 23: 149–154.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo Jr JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright Jr JT, Roccella EJ, the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42: 1206–1252.

Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Narkiewicz K, Ruilope L, Rynkiewicz A, Schmieder RE, Struijker Boudier HA, Zanchetti A, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Kjeldsen SE, Erdine S, Narkiewicz K, Kiowski W, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Cifkova R, Dominiczak A, Fagard R, Heagerty AM, Laurent S, Lindholm LH, Mancia G, Manolis A, Nilsson PM, Redon J, Schmieder RE, Struijker-Boudier HA, Viigimaa M, Filippatos G, Adamopoulos S, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Bertomeu V, Clement D, Erdine S, Farsang C, Gaita D, Kiowski W, Lip G, Mallion JM, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, O’Brien E, Ponikowski P, Redon J, Ruschitzka F, Tamargo J, van Zwieten P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Williams B, Zamorano JL, The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 1462–1536.

Maurer HH . Multi-analyte procedures for screening for and quantification of drugs in blood, plasma, or serum by liquid chromatography-single stage or tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS or LC-MS/MS) relevant to clinical and forensic toxicology. Clin Biochem 2005; 38: 310–318.

Kolocouri F, Dotsikas Y, Apostolou C, Kousoulos C, Loukas YL . Simultaneous determination of losartan, EXP-3174 and hydrochlorothiazide in plasma via fully automated 96-well-format-based solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography-negative electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 2007; 387: 593–601.

Vrijens B, Vincze G, Kristanto P, Urquhart J, Burnier M . Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing histories. BMJ 2008; 336: 1114–1117.

Burke TA, Sturkenboom MC, Lu SE, Wentworth CE, Lin Y, Rhoads GG . Discontinuation of antihypertensive drugs among newly diagnosed hypertensive patients in UK general practice. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 1193–1200.

Mazzaglia G, Mantovani LG, Sturkenboom MC, Filippi A, Trifiro G, Cricelli C, Brignoli O, Caputi AP . Patterns of persistence with antihypertensive medications in newly diagnosed hypertensive patients in Italy: a retrospective cohort study in primary care. J Hypertens 2005; 23: 2093–2100.

Lim LL . Estimating compliance to study medication from serum drug levels: application to an AIDS clinical trial of zidovudine. Biometrics 1992; 48: 619–630.

Serebruany V, Malinin A, Dragan V, Atar D, van Zyl L, Dragan A . Fluorimetric quantitation of citalopram and escitalopram in plasma: developing an express method to monitor compliance in clinical trials. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007; 45: 513–520.

Mani H, Toennes SW, Linnemann B, Urbanek DA, Schwonberg J, Kauert GF, Lindhoff-Last E . Determination of clopidogrel main metabolite in plasma: a useful tool for monitoring therapy? Ther Drug Monit 2008; 30: 84–89.

Maurer HH . Position of chromatographic techniques in screening for detection of drugs or poisons in clinical and forensic toxicology and/or doping control. Clin Chem Lab Med 2004; 42: 1310–1324.

Baroletti S, Dell’Orfano H . Medication adherence in cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2010; 121: 1455–1458.

Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV . Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2002; 288: 462–467.

Waeber B, Leonetti G, Kolloch R, McInnes GT . Compliance with aspirin or placebo in the hypertension optimal treatment (HOT) study. J Hypertens 1999; 17: 1041–1045.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research projects of the Czech Ministry of Health (MZO00179906) and the Czech Ministry of Education (MSM0021620817).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ceral, J., Habrdova, V., Vorisek, V. et al. Difficult-to-control arterial hypertension or uncooperative patients? The assessment of serum antihypertensive drug levels to differentiate non-responsiveness from non-adherence to recommended therapy. Hypertens Res 34, 87–90 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.183

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.183

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

RNA interference in the era of nucleic acid therapeutics

Nature Biotechnology (2024)

-

The effect of combining therapeutic drug monitoring of antihypertensive drugs with personalised feedback on adherence and resistant hypertension: the (RHYME-RCT) trial protocol of a multi-centre randomised controlled trial

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2023)

-

Closing the gap — development of an analytical methodology using volumetric absorptive microsampling of finger prick blood followed by LC-HRMS/MS for adherence monitoring of antihypertensive drugs

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2023)

-

Novel Targets for Hypertension Drug Discovery

Current Hypertension Reports (2021)

-

Dangers of Overly Aggressive Blood Pressure Control

Current Cardiology Reports (2018)