Abstract

Postprandial hypotension (PPH) is a frequently under-recognized entity associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The prevalence of PPH detected through home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) is unknown. To determine the prevalence and clinical predictors of PPH in hypertensive patients assessed through HBPM. Hypertensive patients of 18 years or older underwent home blood pressure (BP) measurements (duplicate measurements for 4 days: in the morning, 1 h before and 1 h after their usual lunch, and in the evening; OMRON 705 CP). PPH was defined as a meal-induced systolic BP decrease of ⩾20 mm Hg. Variables identified as relevant predictors of PPH were entered into a multivariate logistic regression analysis. In total, 230 patients were included in the analysis, with a median age of 73.6 (interquartile range 16.9) years, and 65.2% were female. The prevalence of PPH (at least one episode) was 27.4%. Four variables were independently associated with PPH: age of 80 years or older (odds ratio (OR) 3.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.35–8.82), body mass index (BMI) (OR 0.88, 95%CI 0.81–0.96), office systolic BP (OR 1.03, 95%CI 1.01–1.05) and a history of cerebrovascular disease (OR 3.29, 95%CI 1.03–10.53). PPH after a typical meal is a frequent phenomenon that can be detected through HBPM. Easily measurable parameters in the office such as older age, higher systolic BP, lower BMI and a history of cerebrovascular disease may help to detect patients at risk of PPH who would benefit from HBPM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postprandial hypotension (PPH) is a frequently under-recognized phenomenon associated with increased morbidity, such as syncope, falls, stroke and coronary events, and all-cause mortality.1, 2 Certain populations, namely the elderly, patients diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes, and patients with different causes of autonomic dysfunction, have been identified as particularly vulnerable.3 Although the mechanism involved in PPH is not clearly understood, it appears to be secondary to a blunted sympathetic response to a meal.4

Most studies assessing PPH have been conducted in institutionalized geriatric subjects who consume standardized meals.5, 6 Data from ambulatory patients in their usual environment are scarce, and studies including such patients have used ambulatory blood pressure monitoring as a method to evaluate PPH.7, 8

Home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) is an increasingly used BP measurement strategy that offers some advantages over ambulatory blood pressure monitoring,9, 10 including better patient tolerance, lower cost, and greater suitability for the long-term follow-up of patients under treatment. However, this method has not previously been used to detect PPH in hypertensive patients. The purpose of our study was to determine the prevalence of PPH detected through HBPM in hypertensive subjects and to establish clinical predictors that are easily detectable in a doctor’s office.

Methods

Study population

This was a cross-sectional study that consecutively included hypertensive patients 18 years or older treated in the Hypertension Section of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. The patients performed HBPM as prescribed by their treating physician to assess hypertension control. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and all patients who agreed to participate provided informed consent. The medical records of all patients were reviewed to gather data regarding risk factors (diabetes, smoking status and dyslipidemia), a history of cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral artery disease) and the use of antihypertensive drugs. Laboratory data (fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride levels and serum creatinine) from 6 months before HBPM were also gathered from the medical records.

Patients were asked to complete a diary, recording lunch time and postprandial-related symptoms (dizziness, fatigue and somnolence) during home blood pressure (BP) assessment. The recruitment period lasted from January 2013 to May 2013.

Anthropometric and BP measurements

Weight and height were assessed in all patients, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg m−2). BP was subsequently measured by a trained technician twice in the non-dominant arm, 2 min apart (the average of the two readings was used for analysis), after a 5-min rest with the patient in a sitting position; the arm was always supported at the heart level, and an appropriate cuff size was used according to the arm circumference: patients with an arm circumference of <26 cm used a small adult cuff (12 × 22 cm); patients with an arm circumference between 27 and 34 cm used a standard adult cuff (16 × 30 cm); and patients with an arm circumference of ⩾35 cm used a large adult cuff (16 × 36 cm). For this purpose, an automatic oscillometric device Omron 705 CP (Omron, Tokyo, Japan) was used; this device has previously been validated11 against a mercury sphygmomanometer according to the revised protocol of the British Hypertension Society.12

After receiving appropriate training on its use, the patients returned home with the same oscillometric device used in the office and registered duplicate sitting BP readings (2 min apart) in the non-dominant arm for 4 days: in the morning (before breakfast and medication for those under treatment), 1 h before and 1 h after their usual lunch, and in the evening. Patients were instructed to measure home BP after a 5-min rest, with the legs uncrossed, the back supported and not talking. Additionally, morning readings were taken before breakfast and drug intake. First-day measurements were discarded from the analysis. Patients with <2 days of pre- and postprandial home BP readings were excluded from the analysis.

Definitions of clinical parameters

Hypertension was defined as antihypertensive drug use or a mean (average of morning and evening readings) home systolic or diastolic BP (discarding first-day measurements) of ⩾135 or 85 mm Hg, respectively.

Regarding cardiovascular risk factors, current smoking was defined as the daily use of tobacco products; diabetes was defined as an FPG of ⩾126 mg dl−1 on at least two occasions or the use of antidiabetic drugs; and dyslipidemia was defined according to the ATP III criteria13 or the use of lipid-lowering drugs.

In relation to the history of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease was defined as a history of myocardial infarction, unstable angina, chronic stable angina or coronary bypass surgery; cerebrovascular disease was defined as a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack; and peripheral artery disease was defined as intermittent claudication, abnormal arterial Doppler examination, or peripheral revascularization in the lower limbs.

FPG, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels were all measured in mg dl−1.

Meal-induced BP variation was calculated as the difference between mean BP 1 h before and 1 h following lunchtime, as recorded in the patient’s diary. A meal-induced systolic BP decrease of ⩾20 mm Hg was used to define PPH.14

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as the percentage, mean±standard deviation, or median and interquartile range, according to the data distribution. The characteristics of patients with and without PPH were compared using the t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Variables associated with PPH in the univariate analyses were entered into a multiple logistic regression model to detect independent predictors of PPH. The model’s calibration and discrimination were tested using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, respectively.

Results

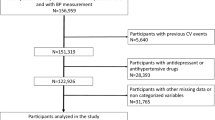

The study included 255 hypertensive patients; 25 (9.8%) had <2 days of pre- and postprandial HBPM readings. Therefore, 230 patients were included in the analysis. The median age was 73.6 (interquartile range 16.9) years, and 150 (65.2%) patients were female (Table 1). Additionally, 91.3% were receiving antihypertensive drugs, with a mean of 2 (±1.1) drugs per patient, and the mean office BP was 139 (±16.2)/78.2 (±9.9) mm Hg.

Overall, meal-induced BP decreases in 5 (±9.8) and 4.4 (±5.5) mm Hg were observed for systolic and diastolic BP, respectively. The home BP and heart rate profiles are depicted in Table 2 and Figures 1 and 2. Interestingly, when the mean home BP was calculated using the morning, evening, and pre- and postprandial readings, the mean was significantly lower than when it was calculated based on the morning and evening BP measurements only, following the current recommendation:15 136.1 (±16.6)/74.6 (±9.6) vs. 131.8 (±14.5)/72.3 (±9.1) mm Hg (P<0.001/0.001).

The prevalence of PPH (at least one episode) was 27.4% (63/230), and 8.7% (20/230) of patients had two or more episodes. Among the 28 subjects who collected only 2 days of pre- and postprandial measurements, 20 had no PPH episodes, 7 had 1 episode and 1 had 2 episodes. The prevalence of the white coat effect among subjects with PPH was not significantly different from those without PPH (19 vs. 24%, P=0.43).

Patients with PPH were older (Figure 3), had a lower BMI, a higher office systolic BP and higher prevalences of beta-blocker use and a history of cerebrovascular disease (Table 1). Univariate logistic regression analyses demonstrated that the following variables were associated with PPH, and they were entered into a multivariate regression model (P-value for goodness-of-fit=0.5; area under the receiver operating characteristic curve=0.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68–0.82): age, BMI, use of beta-blockers, a history of cerebrovascular disease and office systolic BP. Four variables were independently associated with PPH: age of 80 years or older, BMI, office systolic BP and a history of cerebrovascular disease (Table 3).

Discussion

In our study, PPH detected using HBPM was a prevalent phenomenon among hypertensive patients and was associated with older age, lower BMI, a history of cerebrovascular disease and a higher office systolic BP. The reported prevalence of PPH is very heterogenous among studies, ranging from 9 to 70%, depending on the population age, the presence of co-morbidities and the method of BP measurement used.8, 16 The prevalence found in our study was consistent with some studies that also evaluated hypertensive patients and was lower compared with others, perhaps because of the younger population included in our study.7, 8, 17

Age has been evaluated in several studies, including ours, as a PPH predictor, consistently showing a positive association.18, 19 Therefore, elderly people are an already fragile population at risk of suffering from PPH more frequently than younger people, increasing the complexity of hypertension management in such patients. Although our study included subjects 18 years or older, the median age of the population was 73.6 years. Indeed, although we see adult patients in general, most of them are elderly. The average age of patients attending the Hypertension Section of our Hospital is 66 years. In fact, only 26.1% of the patients included in the study were younger than 65 years.

Hypertension is a co-morbidity typically associated with PPH.14 In our study, all subjects had been diagnosed with hypertension, and interestingly, higher office systolic BP was an independent predictor of PPH. This is of particular interest, as the decision to intensify antihypertensive treatment is typically based on office BP measurements only. In that sense, we believe that elderly patients with uncontrolled hypertension may benefit from HBPM before any change in antihypertensive strategy. Future research should aim to establish whether hypertension management considering PPH episodes at home could help to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Decreases in postprandial BP have shown a high correlation with magnetic resonance imaging findings indicative of cerebrovascular damage.2 Moreover, in some prospective studies, PPH has been associated with a higher incidence of transient ischemic attacks20 and stroke,1 which may explain the association between a history of cerebrovascular disease and PPH found in our study.

Low BMI has been associated with orthostatic hypotension,21 but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe such an association with PPH. This could be related to the increased fragility observed in thinner elderly patients.

Other PPH predictors found in previous studies were not statistically significant in our study. Consistent with other studies,8, 22 we failed to find an association between PPH and diabetes, an entity in which autonomic dysfunction has been well documented. A tentative explanation may be that diabetes had recently been diagnosed or was well controlled among our patients. We do not have information on the possible presence of diabetic neuropathy in our population.

In accordance with previous studies,8 PPH was not correlated with the presence of postprandial symptoms. In fact, no differences were found in our study regarding meal-induced BP variation among subjects with and without symptoms. It must be emphasized, however, that asymptomatic PPH is not a benign condition, given its association with asymptomatic cerebrovascular damage.2 Therefore, clinical predictors that may raise the suspicion of PPH in the absence of symptoms may help to identify the patients who would benefit the most from PPH assessment by HBPM or another method. Such screening of asymptomatic hypertensive patients, particularly the elderly, for PPH should be encouraged.

Regarding antihypertensive drugs, some studies have found an association between PPH and diuretics,17, 19 which raises concern about whether antihypertensive drugs should be reduced or withdrawn in such cases. Other studies, including ours, have found no association between PPH and treatment for hypertension.8 Although the univariate analysis in our study indicated an association with beta-blocker use, statistical significance was lost in the multivariate analysis. One possible explanation is that beta-blocker use is related to uncontrolled office hypertension, which persisted as an independent predictor of PPH in the multivariate analysis, given that beta-blockers are not as useful as other drug classes for hypertension therapy in elderly subjects.23, 24 Although discrepancies exist regarding antihypertensive treatment and PPH, it would seem advisable to prescribe antihypertensive drugs away from meal times to avoid exaggerated postprandial BP declines rather than to reduce or discontinue antihypertensive treatment.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use HBPM as an out-of-office measurement method to assess PPH. HBPM provides extensive BP information over a long period of time with high reproducibility, and it has been shown to be better than office BP in the prediction of hypertensive target organ damage and cardiovascular prognosis.25 In our study, we used a 4-day measurement protocol,26, 27 complying with the recommendations of the updated European guidelines on the use of HBPM regarding a monitoring schedule of at least 3 days of measurements.9 In the particular case of PPH assessment, HBPM offers some advantages over ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: it provides pre- and postprandial measurements over several days vs. only 24-h measurements, and given that the patients must be awake to record BP, it avoids a possible ‘napping effect’ that could be observed on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and could act as a confounder for postprandial BP decline. As a result, we believe that HBPM may be a suitable strategy for PPH screening.

One interesting finding in our study was that the average home BP was significantly reduced when considering morning, pre- and postprandial, and evening readings when compared with the currently recommended average of morning and evening measurements only.15, 28 The protocol that should be used to guide treatment in patients at risk of PPH constitutes a matter for future research that may widen HBPM indications.

Finally, our results should be interpreted within the context of the study limitations. First, PPH detected through HBPM has not previously been defined. Although the variability inherent to BP might have influenced the BP decrease after lunch that was observed in our study, we feel that using a decrease of at least 20 mm Hg might have helped to offset this possible confounding factor. Second, patients consumed their usual meals; there was no standardization. However, the lack of standardized meals could be regarded as one study strength because it allows a more ‘real-life’ approach, which may be more useful for physicians making treatment decisions based on this type of information. Third, only lunch-related PPH could be evaluated, as the device used has a limited memory capacity. As a consequence, PPH related to breakfast and dinner could not be assessed. However, even one single episode of PPH has been shown to increase mortality,29 and its detection should not be disregarded. Moreover, lunch has been identified as one of the meals in which greater postprandial BP decreases occur.30 Fourth, subjects receiving antihypertensive drugs took their medication at different times of the day, as they were used to doing before their inclusion in the study. For patients taking their medication near lunchtime, the postprandial BP decrease could have been exaggerated as a result of the drug effect.

In conclusion, PPH was a frequent phenomenon after a typical meal in our study population, particularly in the elderly. HBPM was useful for the detection of PPH and feasible in elderly patients. Easily measurable parameters such as older age, higher office systolic BP, lower BMI, and a history of cerebrovascular disease may help to detect patients at risk of PPH who would benefit from HBPM.

References

Aronow WS, Ahn C . Association of postprandial hypotension with incidence of falls, syncope, coronary events, stroke, and total mortality at 29-month follow-up in 499 older nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45: 1051–1053.

Kohara K, Jiang Y, Igase M, Takata Y, Fukuoka T, Okura T, Kitami Y, Hiwada K . Postprandial hypotension is associated with asymptomatic cerebrovascular damage in essential hypertensive patients. Hypertension 1999; 33: 565–568.

Van Orshoven NP, Jansen PA, Oudejans I, Schoon Y, Oey PL . Postprandial hypotension in clinical geriatric patients and healthy elderly: prevalence related to patient selection and diagnostic criteria. J Aging Res 2010; 2010: 243752.

Luciano GL, Brennan MJ, Rothberg MB . Postprandial hypotension. Am J Med 2010; 123 3: e1–e6.

Tanakaya M, Takahashi N, Takeuchi K, Katayama Y, Yumoto A, Kohno K, Shiraki T, Saito D . Postprandial hypotension due to a lack of sympathetic compensation in patients with diabetes mellitus. Acta Med 2007; 61: 191–197.

Vloet LC, Pel-Little RE, Jansen PA, Jansen RW . High prevalence of postprandial and orthostatic hypotension among geriatric patients admitted to Dutch hospitals. J Gerontol 2005; 60: 1271–1277.

Grodzicki T, Rajzer M, Fagard R, O’Brien ET, Thijs L, Clement D, Davidson C, Palatini P, Parati G, Kocemba J, Staessen JA . Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and postprandial hypotension in elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension in Europe (SYST-EUR) Trial Investigators. J Hum Hypertens 1998; 12: 161–165.

Zanasi A, Tincani E, Evandri V, Giovanardi P, Bertolotti M, Rioli G . Meal- induced blood pressure variation and cardiovascular mortality in ambulatory hypertensive elderly patients: preliminary results. J Hypertens 2012; 30: 2125–2132.

Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, de Leeuw P, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Manolis A, Mengden T, O’Brien E, Ohkubo T, Padfield P, Palatini P, Pickering TJ, Redon J, Revera M, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, Tissler A, Waeber B, Zanchetti A, Mancia G, ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension Practice Guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens 2010; 24: 779–785.

Stergiou GS, Kollias A, Nasothimiou EG . [Home blood pressure monitoring: application in clinical practice[. Hipertens Riesgo Vasc 2011; 28: 149–153.

Artigao LM, Llavador JJ, Puras A, López Abril J, Rubio MM, Torres C, Vidal A, Sanchis C, Divisón JA, Naharro F, Caldevilla D, Fuentes G . Evaluation and validation of Omron Hem 705 CP and Hem 706/711 monitors for self-measurement of blood pressure. Aten Primaria 2000; 25: 96–102.

O’Brien E, Mee F, Atkins N, Thomas M . Evaluation of three devices for self measurement of blood pressure according to the revised British Hypertension Society Protocol: the OMRON HEM-705 CP, Philips HP5332, and Nissei DS-175. Blood Press Monit 1996; 1: 55–61.

Linton MF, Fazio S, National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP)- the third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III). A practical approach to risk assessment to prevent coronary artery disease and its complications. Am J Cardiol 2003; 92: 19i–26i.

Jansen RW, Lipsitz LA . Postprandial hypotension: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122: 286–295.

Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, Krakoff LR, Artinian NT, Goff D . Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension 2008; 52: 10–29.

Puisieux F, Bulckaen H, Fauchais AL, Drumez S, Salomez-Granier F, Dewailly P . Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and postprandial hypotension in elderly persons with falls or syncopes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000; 55: M535–M540.

Mitro P, Feterik K, Cvercková A, Trejbal D . Occurrence and relevance of postprandial hypotension in patients with essential hypertension. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1999; 111: 320–325.

Vaitkevicius PV, Esserwein DM, Maynard AK, O'Connor FC, Fleg JL . Frequency and importance of postprandial blood pressure reduction in elderly nursing-home patients. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115: 865–870.

Aronow WS, Ann C . Postprandial hypotension in 499 elderly persons in a long-term health care facility. Am J Geriatr Soc 1994; 42: 930–932.

Kamata T, Yokota T, Furukawa T, Tsukagoshi H . Cerebral ischemic attack caused by postprandial hypotension. Stroke 1994; 25: 511–513.

Villavicencio-Chávez C, Miralles Basseda R, González Marín P, Cervera AM . [Orthostatic and postprandial hypotension in elderly patients with chronic diseases and disability: prevalence and related factors]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2009; 44: 12–18 (Spanish).

Rhebergen GA, Schölzel-Dorenbos CJ . [Orthostatic and postprandial hypotension in patients aged 70 years or older admitted to a medical ward]. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr 2002; 33: 119–123.

Franklin SS, Gustin W 4th, Wong ND, Larson MG, Weber MA, Kannel WB, Levy D . Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1997; 96: 308–315.

Khan N, McAlister FA . Re-examining the efficacy of beta-blockers for the treatment of hypertension a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2006; 174: 1737–1742.

Imai Y, Obara T, Asayama K, Ohkubo T . The reason why home blood pressure measurements are preferred over clinic or ambulatory blood pressure in Japan. Hypertens Res 2013; 36: 661–672.

Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Jula AM . Optimal schedule for home blood pressure monitoring based on a clinical approach. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 259–264.

Barochiner J, Cuffaro PE, Aparicio LS, Elizondo CM, Giunta DH, Rada MA, Morales MS, Alfie J, Galarza CR, Waisman GD . [Reproducibility and reliability of a 4-day HBPM protocol with and without first day measurements]. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba 2011; 68: 149–153 (Spanish).

Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, de Leeuw P, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Manolis A, Mengden T, O’Brien E, Ohkubo T, Padfield P, Palatini P, Pickering T, Redon J, Revera M, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, Tisler A, Waeber B, Zanchetti A, Mancia G, ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 1505–1526.

Fisher AA, Davis MW, Srikusalanukul W, Budge MM . Postprandial hypotension predicts all-cause mortality in older, low-level care residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1313–1320.

Vloet LC, Smits R, Jansen RW . The effect of meals at different mealtimes on blood pressure and symptoms in geriatric patients with postprandial hypotension. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58: 1031–1035.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ms Erika Barochiner for language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barochiner, J., Alfie, J., Aparicio, L. et al. Postprandial hypotension detected through home blood pressure monitoring: a frequent phenomenon in elderly hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res 37, 438–443 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.144

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.144

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence and related factors of office and home hypotension in older treated hypertensive patients

Aging Clinical and Experimental Research (2019)

-

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postprandial Hypotension among Elderly People Admitted in a Geriatric Evaluation and Management Unit : An Observational Study

The Journal of nutrition, health and aging (2019)

-

Autonomic Neuropathy and Cardiovascular Disease in Aging

The Journal of nutrition, health and aging (2018)

-

Relationship between office and home blood pressure with increasing age: The International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDHOCO)

Hypertension Research (2016)