Key Points

-

p53 functions as the 'guardian of the genome' by inducing cell cycle arrest, senescence and apoptosis in response to oncogene activation, DNA damage and other stress signals. Loss of p53 function occurs in most human tumours by either mutation of TP53 itself or by inactivation of the p53 signal transduction pathway.

-

In many tumours p53 is inactivated by the overexpression of the negative regulators MDM2 and MDM4 or by the loss of activity of the MDM2 inhibitor ARF. The pathway can be reactivated in these tumours by small molecules that inhibit the interaction of MDM2 and/or MDM4 with p53. Such molecules are now in clinical trials.

-

Cell-based screens have been used to find several new non-genotoxic activators of the p53 response, which include inhibitors of protein deacetylating enzymes.

-

Molecules that bind and stabilize mutant p53 — restoring wild-type function — have been discovered by both structure-based design and cell-based screens.

-

Activating a p53-dependent cell cycle arrest in normal cells and tissues can protect them from the toxic effect of anti-mitotic drugs while not reducing their efficacy in killing p53 mutant tumour cells. This drug combination approach represents a new way to exploit the p53 system.

-

The intense study of the p53 pathway is helping to develop new paradigms in drug discovery and development that will have widespread application in other areas of drug discovery.

Abstract

Currently, around 11 million people are living with a tumour that contains an inactivating mutation of TP53 (the human gene that encodes p53) and another 11 million have tumours in which the p53 pathway is partially abrogated through the inactivation of other signalling or effector components. The p53 pathway is therefore a prime target for new cancer drug development, and several original approaches to drug discovery that could have wide applications to drug development are being used. In one approach, molecules that activate p53 by blocking protein–protein interactions with MDM2 are in early clinical development. Remarkable progress has also been made in the development of p53-binding molecules that can rescue the function of certain p53 mutants. Finally, cell-based assays are being used to discover compounds that exploit the p53 pathway by either seeking targets and compounds that show synthetic lethality with TP53 mutations or by looking for non-genotoxic activators of the p53 response.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Paez, J. G. et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 304, 1497–1500 (2004).

Pao, W. et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13306–13311 (2004).

Lynch, T. J. et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med 350, 2129–2139 (2004).

Capdeville, R., Buchdunger, E., Zimmermann, J. & Matter, A. Glivec (STI571, imatinib), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 1, 493–502 (2002).

Baselga, J. & Swain, S. M. Novel anticancer targets: revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3. Nature Rev. Cancer 9, 463–475 (2009).

Clackson, T. & Wells, J. A. A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone-receptor interface. Science 267, 383–386 (1995).

Oltersdorf, T. et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 435, 677–681 (2005).

Vassilev, L. T. et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science 303, 844–848 (2004). This paper describes the successful isolation and characterization of the nutlin compounds that activate p53 by binding to MDM2 and blocking its interaction with p53. The authors show that the molecules are highly specific and active in xenograft models.

Dantzer, F. et al. Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry 39, 7559–7569 (2000).

Ame, J. C., Spenlehauer, C. & de Murcia, G. The PARP superfamily. Bioessays 26, 882–893 (2004).

Edwards, S. L. et al. Resistance to therapy caused by intragenic deletion in BRCA2. Nature 451, 1111–1115 (2008).

Yu, J. & Zhang, L. No PUMA, no death: implications for p53-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell 4, 248–249 (2003).

Moll, U. M., Wolff, S., Speidel, D. & Deppert, W. Transcription-independent pro-apoptotic functions of p53. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 631–636 (2005).

Suzuki, H. I. et al. Modulation of microRNA processing by p53. Nature 460, 529–533 (2009).

Ahn, J. et al. Dissection of the sequence-specific DNA binding and exonuclease activities reveals a superactive yet apoptotically impaired mutant p53 protein. Cell Cycle 8, 1603–1615 (2009).

Mummenbrauer, T. et al. p53 protein exhibits 3'-to-5' exonuclease activity. Cell 85, 1089–1099 (1996).

Sengupta, S. & Harris, C. C. p53: traffic cop at the crossroads of DNA repair and recombination. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 44–55 (2005).

de Souza-Pinto, N. C., Harris, C. C. & Bohr, V. A. p53 functions in the incorporation step in DNA base excision repair in mouse liver mitochondria. Oncogene 23, 6559–6568 (2004).

Sommers, J. A. et al. p53 modulates RPA-dependent and RPA-independent WRN helicase activity. Cancer Res. 65, 1223–1233 (2005).

Budanov, A. V. & Karin, M. p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell 134, 451–460 (2008).

Feng, Z. et al. The regulation of AMPK β1, TSC2, and PTEN expression by p53: stress, cell and tissue specificity, and the role of these gene products in modulating the IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways. Cancer Res. 67, 3043–3053 (2007).

Martins, C. P., Brown-Swigart, L. & Evan, G. I. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell 127, 1323–1334 (2006). This paper shows that restoration of p53 function in tumours using an inducible system is highly effective in inhibiting the growth of even advanced tumours.

Ventura, A. et al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature 445, 661–665 (2007). This paper demonstrates that p53 restoration induced by a genetic switch in a model system leads to tumour regression by apoptosis.

Xue, W. et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 445, 656–660 (2007). This paper shows that in a mouse liver carcinoma model restoration of p53 activity in tumour cells induces senescence rather than cell death. Strikingly, the senescent cells are cleared by an innate immune response.

Bond, G. L., Hu, W. & Levine, A. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene: from a molecular and cellular explanation to clinical effect. Cancer Res. 65, 5481–5484 (2005). In this paper a single nucleotide polymorphism that regulates the expression of MDM2 is shown to affect the probability of developing cancer.

Vousden, K. H. & Lane, D. P. p53 in health and disease. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 275–283 (2007).

Picksley, S. M. & Lane, D. P. The p53-mdm2 autoregulatory feedback loop: a paradigm for the regulation of growth control by p53? Bioessays 15, 689–690 (1993).

Momand, J., Zambetti, G. P., Olson, D. C., George, D. & Levine, A. J. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell 69, 1237–1245 (1992). The original discovery of the p53–MDM2 interaction is described in this paper.

Danovi, D. et al. Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) directly contributes to tumor formation by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 5835–5843 (2004).

Laurie, N. A. et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature 444, 61–66 (2006).

Riemenschneider, M. J. et al. Amplification and overexpression of the MDM4 (MDMX) gene from 1q32 in a subset of malignant gliomas without TP53 mutation or MDM2 amplification. Cancer Res. 59, 6091–6096 (1999).

Esteller, M. et al. p14ARF silencing by promoter hypermethylation mediates abnormal intracellular localization of MDM2. Cancer Res. 61, 2816–2821 (2001).

Sherr, C. J. & Weber, J. D. The ARF/p53 pathway. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10, 94–99 (2000).

Hainaut, P. & Hollstein, M. p53 and human cancer: the first ten thousand mutations. Adv. Cancer Res. 77, 81–137 (2000).

Bullock, A. N., Henckel, J. & Fersht, A. R. Quantitative analysis of residual folding and DNA binding in mutant p53 core domain: definition of mutant states for rescue in cancer therapy. Oncogene 19, 1245–1256 (2000).

Milner, J. & Medcalf, E. A. Cotranslation of activated mutant p53 with wild type drives the wild-type p53 protein into the mutant conformation. Cell 65, 765–774 (1991).

Milner, J., Medcalf, E. A. & Cook, A. C. Tumor suppressor p53: analysis of wild-type and mutant p53 complexes. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 12–19 (1991).

Sigal, A. & Rotter, V. Oncogenic mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor: the demons of the guardian of the genome. Cancer Res. 60, 6788–6793 (2000).

Levine, A. J. et al. The spectrum of mutations at the p53 locus. Evidence for tissue-specific mutagenesis, selection of mutant alleles, and a “gain of function” phenotype. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 768, 111–128 (1995).

Irwin, M. S. Family feud in chemosensitvity: p73 and mutant p53. Cell Cycle 3, 319–323 (2004).

Li, Y. & Prives, C. Are interactions with p63 and p73 involved in mutant p53 gain of oncogenic function? Oncogene 26, 2220–2225 (2007).

Strano, S. et al. Mutant p53: an oncogenic transcription factor. Oncogene 26, 2212–2219 (2007).

Kim, E. & Deppert, W. Transcriptional activities of mutant p53: when mutations are more than a loss. J. Cell Biochem. 93, 878–886 (2004).

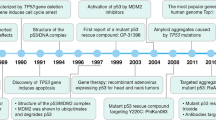

Levine, A. J. & Oren, M. The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nature Rev. Cancer 9, 749–758 (2009).

Selivanova, G. et al. Restoration of the growth suppression function of mutant p53 by a synthetic peptide derived from the p53 C-terminal domain. Nature Med. 3, 632–638 (1997).

Foster, B. A., Coffey, H. A., Morin, M. J. & Rastinejad, F. Pharmacological rescue of mutant p53 conformation and function. Science 286, 2507–2510 (1999).

Joerger, A. C., Ang, H. C. & Fersht, A. R. Structural basis for understanding oncogenic p53 mutations and designing rescue drugs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15056–15061 (2006). This paper describes the first key step in the rational design of specific drugs that can re-activate p53 by binding to it and protecting it from unfolding.

Shangary, S. et al. Temporal activation of p53 by a specific MDM2 inhibitor is selectively toxic to tumors and leads to complete tumor growth inhibition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3933–3938 (2008).

Bykov, V. J. et al. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function to mutant p53 by a low-molecular-weight compound. Nature Med. 8, 282–288 (2002). In this paper the authors use a cell-based screen to search for molecules that only kill cells expressing mutant p53. They identify PRIMA-1 as a compound that has this activity and can restore wild-type p53 function to mutant p53. A modified version of Prima-1 (APR-246) is now in clinical trials.

Lain, S. et al. Discovery, in vivo activity, and mechanism of action of a small-molecule p53 activator. Cancer Cell 13, 454–463 (2008). This paper describes a cell-based screen that leads to the identification of new p53-activating molecules. The target of these new molecules is then defined using a genetic screen in yeast that shows that they function by blocking the deacetylation of p53 by the sirtuins.

Issaeva, N. et al. Small molecule RITA binds to p53, blocks p53-HDM-2 interaction and activates p53 function in tumors. Nature Med. 10, 1321–1328 (2004).

Sur, S. et al. A panel of isogenic human cancer cells suggests a therapeutic approach for cancers with inactivated p53. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3964–3969 (2009). An exciting study that shows that prior activation of the p53 pathway with the MDM2 inhibitor nutlin protects against the neutrophil depletion that is induced by mitotic inhibitors that block the activity of PLK1. Using this drug combination can alleviate the side effects of chemotherapy without reducing its ability to kill p53 mutant tumour cells.

Cheok, C. F., Dey, A. & Lane, D. P. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors sensitize tumor cells to nutlin-induced apoptosis: a potent drug combination. Mol. Cancer Res. 5, 1133–1145 (2007).

Fang, B. & Roth, J. A. Tumor-suppressing gene therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2, S115–121 (2003).

Nishizaki, M. et al. Recombinant adenovirus expressing wild-type p53 is antiangiogenic: a proposed mechanism for bystander effect. Clin. Cancer Res. 5, 1015–1023 (1999).

McCormick, F. Cancer-specific viruses and the development of ONYX-015. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2, S157–160 (2003).

Joerger, A. C. & Fersht, A. R. Structural biology of the tumor suppressor p53. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 557–582 (2008).

Terzian, T. et al. The inherent instability of mutant p53 is alleviated by Mdm2 or p16INK4a loss. Genes Dev. 22, 1337–1344 (2008).

Hupp, T. R., Meek, D. W., Midgley, C. A. & Lane, D. P. Regulation of the specific DNA binding function of p53. Cell 71, 875–886 (1992).

Hupp, T. R., Sparks, A. & Lane, D. P. Small peptides activate the latent sequence-specific DNA binding function of p53. Cell 83, 237–245 (1995).

Selivanova, G., Ryabchenko, L., Jansson, E., Iotsova, V. & Wiman, K. G. Reactivation of mutant p53 through interaction of a C-terminal peptide with the core domain. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 3395–3402 (1999).

Kim, A. L. et al. Conformational and molecular basis for induction of apoptosis by a p53 C-terminal peptide in human cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34924–34931 (1999).

Snyder, E. L., Meade, B. R., Saenz, C. C. & Dowdy, S. F. Treatment of terminal peritoneal carcinomatosis by a transducible p53-activating peptide. PLoS Biol. 2, E36 (2004).

Lane, D. Curing cancer with p53. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2711–2712 (2004).

Rippin, T. M. et al. Characterization of the p53-rescue drug CP-31398 in vitro and in living cells. Oncogene 21, 2119–2129 (2002).

Stephen, C. W. & Lane, D. P. Mutant conformation of p53. Precise epitope mapping using a filamentous phage epitope library. J. Mol. Biol. 225, 577–583 (1992).

Milner, J., Cook, A. & Sheldon, M. A new anti-p53 monoclonal antibody, previously reported to be directed against the large T antigen of simian virus 40. Oncogene 1, 453–455 (1987).

Milner, J. Flexibility: the key to p53 function? Trends Biochem. Sci. 20, 49–51 (1995).

Boeckler, F. M. et al. Targeted rescue of a destabilized mutant of p53 by an in silico screened drug. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10360–10365 (2008).

Haggarty, S. J. et al. Dissecting cellular processes using small molecules: identification of colchicine-like, taxol-like and other small molecules that perturb mitosis. Chem. Biol. 7, 275–286 (2000).

Lambert, J. M. et al. PRIMA-1 reactivates mutant p53 by covalent binding to the core domain. Cancer Cell 15, 376–388 (2009).

Kudo, N. et al. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9112–9117 (1999).

Farmer, H. et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005).

Oliner, J. D., Kinzler, K. W., Meltzer, P. S., George, D. L. & Vogelstein, B. Amplification of a gene encoding a p53-associated protein in human sarcomas. Nature 358, 80–83 (1992).

Momand, J., Jung, D., Wilczynski, S. & Niland, J. The MDM2 gene amplification database. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 3453–3459 (1998).

Mendrysa, S. M. et al. Tumor suppression and normal aging in mice with constitutively high p53 activity. Genes Dev. 20, 16–21 (2006). An elegant paper that uses hypomorphic alleles of Mdm2 to show that slightly increased levels of p53 activity can allow normal growth while blocking tumour development.

Tovar, C. et al. Small-molecule MDM2 antagonists reveal aberrant p53 signaling in cancer: implications for therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 1888–1893 (2006).

Grasberger, B. L. et al. Discovery and cocrystal structure of benzodiazepinedione HDM2 antagonists that activate p53 in cells. J. Med. Chem. 48, 909–912 (2005).

Ding, K. et al. Structure-based design of potent non-peptide MDM2 inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10130–10131 (2005).

Ding, K. et al. Structure-based design of spiro-oxindoles as potent, specific small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 interaction. J. Med. Chem. 49, 3432–3435 (2006).

Koblish, H. K. et al. Benzodiazepinedione inhibitors of the Hdm2:p53 complex suppress human tumor cell proliferation in vitro and sensitize tumors to doxorubicin in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 160–169 (2006).

Leonard, K. et al. Novel 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-diones as Hdm2 antagonists with improved cellular activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 3463–3468 (2006).

Parks, D. J. et al. Enhanced pharmacokinetic properties of 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-dione antagonists of the HDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction through structure-based drug design. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 3310–3314 (2006).

Shangary, S. & Wang, S. Small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction to reactivate p53 function: a novel approach for cancer therapy. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 49, 223–241 (2009).

Parant, J. et al. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4-null mice by loss of Trp53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate p53. Nature Genet. 29, 92–95 (2001).

Montes de Oca Luna, R., Wagner, D. S. & Lozano, G. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature 378, 203–206 (1995). This paper and reference 75 establish that p53 can induce embryonic lethality if it is not regulated by MDM2.

Jones, S. N., Roe, A. E., Donehower, L. A. & Bradley, A. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature 378, 206–208 (1995).

Stad, R. et al. Mdmx stabilizes p53 and Mdm2 via two distinct mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 2, 1029–1034 (2001).

Linke, K. et al. Structure of the MDM2/MDMX RING domain heterodimer reveals dimerization is required for their ubiquitylation in trans. Cell Death Differ. 15, 841–848 (2008).

Tanimura, S. et al. MDM2 interacts with MDMX through their RING finger domains. FEBS Lett. 9447, 5–9 (1999).

Sharp, D. A., Kratowicz, S. A., Sank, M. J. & George, D. L. Stabilization of the MDM2 oncoprotein by interaction with the structurally related MDMX protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 38189–38196 (1999).

Linares, L. K., Hengstermann, A., Ciechanover, A., Muller, S. & Scheffner, M. HdmX stimulates Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 12009–12014 (2003).

Gu, J. et al. Mutual dependence of MDM2 and MDMX in their functional inactivation of p53. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19251–19254 (2002).

Pan, Y. & Chen, J. MDM2 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of MDMX. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 5113–5121 (2003).

Kawai, H. et al. DNA damage-induced MDMX degradation is mediated by MDM2. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45946–45953 (2003).

de Graaf, P. et al. Hdmx protein stability is regulated by the ubiquitin ligase activity of Mdm2. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38315–38324 (2003).

Wade, M. & Wahl, G. M. Targeting Mdm2 and Mdmx in cancer therapy: better living through medicinal chemistry? Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1–11 (2009).

Ramos, Y. F. et al. Aberrant expression of HDMX proteins in tumor cells correlates with wild-type p53. Cancer Res. 61, 1839–1842 (2001).

Bartel, F. et al. Significance of HDMX-S (or MDM4) mRNA splice variant overexpression and HDMX gene amplification on primary soft tissue sarcoma prognosis. Int. J. Cancer 117, 469–475 (2005).

Bottger, V. et al. Comparative study of the p53-mdm2 and p53-MDMX interfaces. Oncogene 18, 189–199 (1999).

Pazgier, M. et al. Structural basis for high-affinity peptide inhibition of p53 interactions with MDM2 and MDMX. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4665–4670 (2009).

Bernal, F., Tyler, A. F., Korsmeyer, S. J., Walensky, L. D. & Verdine, G. L. Reactivation of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway by a stapled p53 peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2456–2457 (2007).

Czarna, A. et al. High affinity interaction of the p53 peptide-analogue with human Mdm2 and Mdmx. Cell Cycle 8, 1176–1184 (2009).

Karlsson, G. B. et al. Activation of p53 by scaffold-stabilised expression of Mdm2-binding peptides: visualisation of reporter gene induction at the single-cell level. Br. J. Cancer 91, 1488–1494 (2004).

Yang, Y. et al. Small molecule inhibitors of HDM2 ubiquitin ligase activity stabilize and activate p53 in cells. Cancer Cell 7, 547–559 (2005).

Brummelkamp, T. R. et al. An shRNA barcode screen provides insight into cancer cell vulnerability to MDM2 inhibitors. Nature Chem. Biol. 2, 202–206 (2006).

Dayal, S. et al. Suppression of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 causes the accumulation of unanchored polyubiquitin and the activation of p53. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5030–5041 (2009).

Lane, D. P. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature 358, 15–16 (1992). The news and views commentary that named p53 as “guardian of the genome”, emphasizing its role in the DNA damage response.

Sohn, T. A., Bansal, R., Su, G. H., Murphy, K. M. & Kern, S. E. High-throughput measurement of the Tp53 response to anticancer drugs and random compounds using a stably integrated Tp53-responsive luciferase reporter. Carcinogenesis 23, 949–957 (2002).

Berkson, R. G. et al. Pilot screening programme for small molecule activators of p53. Int. J. Cancer 115, 701–710 (2005).

Gurova, K. V. et al. Small molecules that reactivate p53 in renal cell carcinoma reveal a NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism of p53 suppression in tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 17448–17453 (2005).

Maclean, K. H., Dorsey, F. C., Cleveland, J. L. & Kastan, M. B. Targeting lysosomal degradation induces p53-dependent cell death and prevents cancer in mouse models of lymphomagenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 79–88 (2008).

Gottifredi, V., Shieh, S., Taya, Y. & Prives, C. p53 accumulates but is functionally impaired when DNA synthesis is blocked. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1036–1041 (2001).

Sun, X. X., Dai, M. S. & Lu, H. Mycophenolic acid activation of p53 requires ribosomal proteins L5 and L11. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12387–12392 (2008).

Linke, S. P., Clarkin, K. C., Di Leonardo, A., Tsou, A. & Wahl, G. M. A reversible, p53-dependent G0/G1 cell cycle arrest induced by ribonucleotide depletion in the absence of detectable DNA damage. Genes Dev. 10, 934–947 (1996).

te Poele, R. H., Okorokov, A. L. & Joel, S. P. RNA synthesis block by 5,6-dichloro-1-β-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB) triggers p53-dependent apoptosis in human colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene 18, 5765–5772 (1999).

Ljungman, M., Zhang, F., Chen, F., Rainbow, A. J. & McKay, B. C. Inhibition of RNA polymerase II as a trigger for the p53 response. Oncogene 18, 583–592 (1999).

Choong, M. L., Yang, H., Lee, M. A. & Lane, D. P. Specific activation of the p53 pathway by low dose actinomycin D: A new route to p53 based cyclotherapy. Cell Cycle 8, 2810–2818 (2009).

Lohrum, M. A., Ludwig, R. L., Kubbutat, M. H., Hanlon, M. & Vousden, K. H. Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell 3, 577–587 (2003).

Lindstrom, M. S., Jin, A., Deisenroth, C., White Wolf, G. & Zhang, Y. Cancer-associated mutations in the MDM2 zinc finger domain disrupt ribosomal protein interaction and attenuate MDM2-induced p53 degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 1056–1068 (2007).

Rubbi, C. P. & Milner, J. Disruption of the nucleolus mediates stabilization of p53 in response to DNA damage and other stresses. EMBO J. 22, 6068–6077 (2003).

Foster, S. A., Demers, G. W., Etscheid, B. G. & Galloway, D. A. The ability of human papillomavirus E6 proteins to target p53 for degradation in vivo correlates with their ability to abrogate actinomycin D-induced growth arrest. J. Virol. 68, 5698–5705 (1994).

Green, D. M. et al. Comparison between single-dose and divided-dose administration of dactinomycin and doxorubicin for patients with Wilms' tumor: a report from the National Wilms' Tumor Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 16, 237–245 (1998).

Staples, O. D. et al. Characterization, chemical optimization and anti-tumour activity of a tubulin poison identified by a p53-based phenotypic screen. Cell Cycle 7, 3417–3427 (2008).

Krajewski, M., Ozdowy, P., D'Silva, L., Rothweiler, U. & Holak, T. A. NMR indicates that the small molecule RITA does not block p53-MDM2 binding in vitro. Nature Med. 11, 1135–1136 (2005).

Yang, J. et al. Small-molecule activation of p53 blocks hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in vivo and leads to tumor cell apoptosis in normoxia and hypoxia. Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 2243–2253 (2009).

Rivera, M. I. et al. Selective toxicity of the tricyclic thiophene NSC 652287 in renal carcinoma cell lines: differential accumulation and metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 57, 1283–1295 (1999).

Nieves-Neira, W. et al. DNA protein cross-links produced by NSC 652287, a novel thiophene derivative active against human renal cancer cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 56, 478–484 (1999).

Yang, J., Ahmed, A. & Ashcroft, M. Activation of a unique p53-dependent DNA damage response. Cell Cycle 8, 1630–1632 (2009).

Enge, M. et al. MDM2-dependent downregulation of p21 and hnRNP K provides a switch between apoptosis and growth arrest induced by pharmacologically activated p53. Cancer Cell 15, 171–183 (2009).

Grinkevich, V. V. et al. Ablation of key oncogenic pathways by RITA-reactivated p53 is required for efficient apoptosis. Cancer Cell 15, 441–453 (2009).

Luo, J. et al. Negative control of p53 by Sir2α promotes cell survival under stress. Cell 107, 137–148 (2001).

Vaziri, H. et al. hSIR2SIRT1 functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell 107, 149–159 (2001).

Langley, E. et al. Human SIR2 deacetylates p53 and antagonizes PML/p53-induced cellular senescence. EMBO J. 21, 2383–2396 (2002).

Mutka, S. C. et al. Identification of nuclear export inhibitors with potent anticancer activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 69, 510–517 (2009).

Blagosklonny, M. V. Basic cell cycle and cancer research: is harmony impossible? Cell Cycle 1, 3–5 (2002).

Carvajal, D. et al. Activation of p53 by MDM2 antagonists can protect proliferating cells from mitotic inhibitors. Cancer Res. 65, 1918–1924 (2005).

Soucek, L. et al. Modelling Myc inhibition as a cancer therapy. Nature 455, 679–683 (2008).

van Montfort, R. L. & Workman, P. Structure-based design of molecular cancer therapeutics. Trends Biotechnol. 27, 315–328 (2009).

Nienaber, V. et al. Discovering novel ligands for macromolecules using X-ray crystallographic screening. Nature Biotechnol. 18, 1105–1108 (2000).

Wang, Y. V., Leblanc, M., Wade, M., Jochemsen, A. G., Wahl, G. M. Increased radioresistance and accelerated B Cell lymphomas in mice with Mdmx mutations that prevent modifications by DNA-damage-activated kinases. Cancer Cell 16, 33–43 (2009).

Vassilev, L. T. MDM2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 13, 23–31 (2007).

Zhang, Y. & Xiong, Y. Control of p53 ubiquitination and nuclear export by MDM2 and ARF. Cell Growth Differ. 12, 175–186 (2001).

Robertson, K. D. & Jones, P. A. The human ARF cell cycle regulatory gene promoter is a CpG island which can be silenced by DNA methylation and down-regulated by wild-type p53. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 6457–6473 (1998).

Honda, R. & Yasuda, H. Activity of MDM2, a ubiquitin ligase, toward p53 or itself is dependent on the RING finger domain of the ligase. Oncogene 19, 1473–1476 (2000).

Fang, S., Jensen, J. P., Ludwig, R. L., Vousden, K. H. & Weissman, A. M. Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8945–8951 (2000).

Newlands, E. S., Rustin, G. J., Brampton, M. H. Phase I trial elactocin. Br. J. Cancer 74, 648–649 (1996).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Related links

Glossary

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy

-

Cell-killing drugs used to treat various cancers by targeting rapidly dividing cells.

- Missense mutation

-

A single nucleotide is changed, resulting in a codon that encodes a different amino acid (non-synonymous).

- Forward chemical genetics

-

FCG. Libraries of small molecules are screened for their ability to induce a particular phenotype in cells or cellular extracts. FCG requires three components: a collection of compounds, a biological assay with a quantifiable phenotypic output and a method to identify the target(s) of the active compounds.

- Differential scanning calorimetry

-

Measures the heat changes that occur in biomolecules during controlled increases or decreases in temperature. It measures the enthalpy of unfolding and the change in heat capacity owing to heat denaturation: the higher the thermal transition (melting point) the more stable the molecule.

- Michael acceptor

-

The Michael reaction occurs between a Michael donor (such as cysteine residues in proteins) and a Michael acceptor molecule (such as leptomycin B) in the presence of a base. The reaction itself is the nucleophillic addition of a carbanion to an α-, β-unsaturated carbonyl compound.

- Synthetic lethality

-

Two genes are in a synthetic lethal relationship if a mutation in both genes leads to cell death but a mutation in one gene alone does not.

- Aptamers

-

Molecules that interact with a specific target molecule usually generated from a large random artificial library, which can be RNA-, DNA-, peptide- or protein-based.

- Cis-imidazoline compounds

-

A class of compounds synthesized around a core imidazole structure, such as the nutlins.

- Benzodiazepenes

-

Chemical compounds with a core chemical structure that is the fusion of a benzene ring and a diazepine ring.

- Spiro-oxindole

-

A molecule with a core scaffold that contains a tryptophan-like structure.

- IC50

-

The concentration of a drug that causes a 50% inhibition of the activity of a target enzyme.

- Topoisomerse inhibitors

-

Chemotherapy agents that interfere with the actions of topoisomerase 1 and topoisomerase 2, which are involved in DNA replication during the cell cycle.

- Taxol

-

A compound that stabilizes microtubules by irreversibly binding to the β-subunit of tubulin.

- Vinca alkaloids

-

Anti-mitotic and anti-microtubule agents that prevent tubulin polymerization and so interfere with chromosomal replication and subsequent separation.

- Roscovitine

-

An olomoucine-related purine flavopiridol, which is a highly potent inhibitor of the kinase activity of cyclin-dependent kinases CDK1, CDK2, CDK5 and CDK7. It induces the activation, stabilization and accumulation of p53 in the nucleus through the suppression of MDM2 expression and partial inhibition of its transcription.

- Neutropenia

-

A haematological disorder characterized by an abnormally low number of neurophils.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, C., Lain, S., Verma, C. et al. Awakening guardian angels: drugging the p53 pathway. Nat Rev Cancer 9, 862–873 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2763

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2763

This article is cited by

-

Design-rules for stapled peptides with in vivo activity and their application to Mdm2/X antagonists

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Helicobacter pylori-induced NAT10 stabilizes MDM2 mRNA via RNA acetylation to facilitate gastric cancer progression

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2023)

-

Convergent TP53 loss and evolvability in cancer

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2023)

-

Homogenous TP53mut-associated tumor biology across mutation and cancer types revealed by transcriptome analysis

Cell Death Discovery (2023)

-

Synthesis and applications of mirror-image proteins

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)