Key Points

-

Sepsis generates estimated costs of >US $16 billion annually in the United States alone, and causes >200,000 deaths per year. However, despite considerable efforts, only one novel therapy has achieved regulatory approval in the past two decades.

-

If sepsis is defined conceptually as the clinical syndrome that results from the host response to invasive infection, then potential sepsis therapies can be categorized as those that target the inciting infection, those that are directed against the response of the host and those that treat the clinical sequelae of this process. Trials of each of these types of therapy are described.

-

Possible reasons for the lack of success of most potential sepsis therapies are discussed, including: absence or loss of the agent's biological activity; inappropriate dose, duration or timing of therapy; heterogeneity of the target population; and limitations of outcome measures.

-

A rational, sequential approach to the evaluation of novel therapies in sepsis is put forward.

Abstract

Sepsis, a life-threatening disorder that arises through the body's response to infection, is the leading cause of death and disability for patients in an intensive care unit. Advances in the understanding of the complex biological processes responsible for the clinical syndrome have led to the identification of many promising new therapeutic targets, including bacterial toxins, host-derived mediators, and downstream processes such as coagulation and the endocrine response. Diverse therapies directed against these targets have shown dramatic effects in animal models; however, in humans, their impact has been frustratingly modest, and only one agent — recombinant activated protein C — has achieved regulatory approval. This review summarizes the approaches that have been evaluated in clinical trials, explores the reasons for the discordance between biological promise and clinical reality, and points to approaches that may lead to greater success in the future.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bone, R. C. Sepsis and controlled clinical trials: The odyssey continues. Crit. Care Med. 23, 1313–1315 (1995).

Nasraway, S. A. Sepsis research: We must change course. Crit. Care Med. 27, 427–430 (1999).

Angus, D. C. et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care Med. 29, 1303–1310 (2001). Using administrative data from seven states, and representing a quarter of the US population, this paper provides the best contemporary estimate of the prevalence and clinical and economic impact of sepsis in the United States.

Bernard, G. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 699–709 (2001). This manuscript reports the results of the pivotal trial of recombinant human activated protein C (drotecogin alpha activated) in sepsis. A statistically significant survival benefit of 6.1% in treated patients led to the first FDA approval of a recombinant protein for the treatment of sepsis.

Annane, D. et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA 288, 862–871 (2002). A multicentre French study that showed a statistically significant survival benefit when patients with vasopressor-dependent septic shock who showed impaired responses to an adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test were treated with a combination of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone.

Michalek, S. M., Moore, R. N., McGhee, J. R., Rosenstreich, D. L. & Mergenhagen, S. E. The primary role of lymphoreticular cells in the mediation of host responses to bacterial endotoxin. J. Infect. Dis. 141, 55–63 (1980).

Poltorak, A. et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: Mutations in the Tlr4 gene. Science 282, 2085–2088 (1998).

Anderson, K. V. Toll signaling pathways in the innate immune response. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 13–19 (2000).

Wang, H. et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 285, 248–251 (1999).

Brealey, D. et al. Association between mitochondrial dysfunction and severity and outcome of septic shock. Lancet 360, 219–223 (2002).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Sepsis-induced apoptosis causes progressive profound depletion of B and CD4+ T lymphocytes in humans. J. Immunol. 166, 6952–6963 (2001).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Rapid onset of intestinal epithelial and lymphocyte apoptotic cell death in patients with trauma and shock. Crit. Care Med. 28, 3207–3217 (2000).

Beutler, B., Milsark, I. W. & Cerami, A. C. Passive immunization against cachectin tumor necrosis factor protects mice from lethal effect of endotoxin. Science 229, 869–871 (1985). This paper provided the first evidence that the neutralization of an endogenous host-derived mediator of inflammation could improve survival in an animal model of endotoxin challenge.

Tracey, K. J. et al. Anti-cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteraemia. Nature 330, 662–664 (1987).

Hinshaw, L. B. et al. Lethal Staphylococcus aureus-induced shock in primates: prevention of death with anti-TNF monoclonal antibody. J. Trauma 33, 568–573 (1992).

Zhao, B., Bowden, R. A., Stavchansky, S. A. & Bowman, P. D. Human endothelial cell response to gram-negative lipopolysaccharide assessed with cDNA microarrays. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281, C1587–C1595 (2001).

Fessler, M. B., Malcolm, K. C., Duncan, M. W. & Worthen, G. S. A genomic and proteomic analysis of activation of the human neutrophil by lipopolysaccharide and its mediation by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31291–31302 (2002).

Lin, E. & Lowry, S. F. The human response to endotoxin. Sepsis 2, 255–262 (1998).

Taveira Da Silva, A. M. et al. Brief report: shock and multiple organ dysfunction after self administration of salmonella endotoxin. N. Engl. J. Med. 328, 1457–1460 (1993).

Roumen, R. M. H. et al. Endotoxemia after major vascular operations. J. Vasc. Surg. 18, 853–857 (1993).

Riddington, D. W. et al. Intestinal permeability, gastric intramucosal pH, and systemic endotoxemia in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. JAMA 275, 1007–1012 (1996).

Ziegler, E. J. et al. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and shock with human antiserum to a mutant Escherichia coli. N. Engl. J. Med. 307, 1225–1230 (1982).

Baumgartner, J. D. et al. Prevention of gram negative shock and death in surgical patients by antibody to endotoxin core glycolipid. Lancet 1, 59–63 (1985).

Ziegler, E. J. et al. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and septic shock with HA-1A human monoclonal antibody against endotoxin. N. Engl. J. Med. 324, 429–436 (1991).

McCloskey, R. V. et al. Treatment of septic shock with human monoclonal antibody HA-1A. Ann. Intern. Med. 121, 1–5 (1994).

Albertson, T. E. et al. Multicenter evaluation of a human monoclonal antibody to Enterobacteriaceae common antigen in patients with Gram-negative sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 31, 419–427 (2003).

Wilde, C. G. et al. Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein. LPS binding properties and effects on LPS-mediated cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17411–17416 (1994).

Rintala, E., Peuravuori, H., Pulkki, K., Voipio-Pulkki, L. M. & Nevalainen, T. Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI) in sepsis correlates with the severity of sepsis and the outcome. Intensive Care Med. 26, 1248–1251 (2000).

Levin, M. et al. Recombinant bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (rBPI21) as adjunctive treatment for children with severe meningococcal sepsis: a randomised trial. Lancet 356, 961–967 (2000). Describes a multicentre, randomized trial of recombinant bactericidal permeability-increasing protein in paediatric meningococcemia. The baseline mortality in the placebo arm was low, with the result that a mortality benefit could not be demonstrated; however, the authors showed a significant improvement in morbidity resulting from therapy.

Larrick, J. W. et al. Human CAP18: a novel antimicrobial lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 63, 1291–1297 (1995).

Willatts, S. M., Radford, S. & Leitermann, M. Effect of the antiendotoxic agent, taurolidine, in the treatment of sepsis syndrome: A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Crit. Care Med. 23, 1033–1039 (1995).

Flegel, W. A., Wölpl, A., Männel, D. N. & Northoff, H. Inhibition of endotoxin induced activation of human monocytes by human lipoproteins. Infect. Immun. 57, 2237–2245 (1989).

Christ, W. J. et al. E5531, a pure endotoxin antagonist of high potency. Science 269, 80–83 (1995).

Poelstra, K. et al. Dephosphorylation of endotoxin by alkaline phosphatase in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 151, 1163–1169 (1997).

Hanasawa, K. Extracorporeal treatment for septic patients: new adsorption technologies and their clinical application. Ther. Apher. 6, 290–295 (2002).

Alejandria, M. M., Lansang, M. A., Dans, L. F. & Mantaring, J. B. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treating sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD001090 (2002).

Werdan, K. Intravenous immunoglobulin for prophylaxis and therapy of sepsis. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 7, 354–361 (2001).

Goeddel, D. V. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor. Chest 116, S69–S73 (1999).

Cannon, J. G. et al. Circulating interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor in septic shock and experimental endotoxin fever. J. Infect. Dis. 161, 79–84 (1990).

Michie, H. R. et al. Tumor necrosis factor and endotoxin induce similar metabolic responses in human beings. Surgery 104, 280–286 (1988).

van der Poll, T. et al. Activation of coagulation after administration of tumor necrosis factor to normal subjects. N. Engl. J. Med. 322, 1622–1627 (1990).

Damas, P. et al. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 serum levels during severe sepsis in humans. Crit. Care Med. 17, 975–978 (1989).

Debets, J. M. H., Kampmeijer, R., van der Linden, M. P. M. H., Buurman, W. A. & Van der Linden, C. J. Plasma tumor necrosis factor and mortality in critically ill septic patients. Crit. Care Med. 17, 489–494 (1989).

Borrelli, E. et al. Plasma concentrations of cytokines, their soluble receptors, and antioxidant vitamins can predict the development of multiple organ failure in patients at risk. Crit. Care Med. 24, 392–397 (1996).

Abraham, E. et al. p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein in the treatment of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. JAMA 277, 1531–1538 (1997).

Abraham, E. et al. Lenercept (p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein) in severe sepsis and early septic shock: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial with 1,342 patients. Crit. Care Med. 29, 503–510 (2001).

Fisher, C. J. Jr et al. Treatment of septic shock with the tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 1697–1702 (1996).

Criscione, L. G. & St Clair, E. W. Tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists for the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 14, 204–211 (2002).

Fisher, C. J. et al. Influence of an anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody on cytokine level in patients with sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 21, 318–327 (1993).

Dhainaut, J. F. et al. CDP571, a humanized antibody to human tumor necrosis factor-α: safety, pharmacokinetics, immune response, and influence of the antibody on cytokine concentrations in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 23, 1461–1469 (1995).

Clark, M. A. et al. Effect of a chimeric antibody to tumor necrosis factor-α on cytokine and physiologic responses in patients with severe sepsis: a randomized clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 26, 1650–1659 (1998).

Abraham, E. et al. Efficacy and safety of monoclonal antibody to human tumor necrosis factor α in patients with sepsis syndrome. A randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. JAMA 273, 934–941 (1995).

Cohen, J. & Carlet, J. INTERSEPT: An international, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of monoclonal antibody to human tumor necrosis factor-α in patients with sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 24, 1431–1440 (1996).

Abraham, E. et al. Double-blind randomised controlled trial of monoclonal antibody to human tumour necrosis factor in treatment of septic shock. Lancet 351, 929–933 (1998).

Reinhart, K. et al. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of the monnoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody-fragmennt, MAK 195F, in patients with sepsis and septic shock: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Crit. Care Med. 24, 733–742 (1996).

Panacek, E. A. et al. Neutralization of TNF by a monoclonal antibody improves survival and reduces organ dysfunction in human sepsis: Results of the MONARCS trial. Chest 118, S88 (2000).

Gallagher, J. et al. A multicenter, open-label, prospective, randomized, dose-ranging pharmacokinetic study of the anti-TNF-α antibody afelimomab in patients with sepsis syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 27, 1169–1178 (2001).

Dinarello, C. A. Biological basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 87, 2095–2147 (1996).

Arend, W. P. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. A new member of the interleukin 1 family. J. Clin. Invest. 88, 1445–1451 (1991).

Tilg, H., Vannier, E., Vachino, G., Dinarello, C. A. & Mier, J. W. Antiinflammatory properties of hepatic acute phase proteins: Preferential induction of interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist over IL-1β synthesis by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Exp. Med. 178, 1629–1636 (1993).

Fisher, C. J. Jr et al. Initial evaluation of human recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of sepsis syndrome: A randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Crit. Care Med. 22, 12–21 (1994).

Fisher, C. J. et al. Recombinant human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of patients with sepsis syndrome. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. JAMA 271, 1836–1843 (1994).

Opal, S. M. et al. Confirmatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist trial in severe sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Crit. Care Med. 25, 1115–1124 (1997).

Bulger, E. M. & Maier, R. V. Lipid mediators in the pathohysiology of critical illness. Crit. Care Med. 28, N36 (2000).

Murakami, M. & Kudo, I. Phospholipase A2 . J. Biochem. 131, 285–292 (2002).

Touqui, L. & Alaoui-El-Azher, M. Mammalian secreted phospholipases A2 and their pathophysiological significance in inflammatory diseases. Curr. Mol. Med. 1, 739–754 (2001).

Uhl, W. et al. A multicenter study of phospholipase A2 in patients in intensive care units. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 180, 323–331 (1995).

Springer, D. M. An update on inhibitors of human 14 kDa Type II s-PLA2 in development. Curr. Pharm. Des. 7, 181–198 (2001).

Zimmerman, G. A., McIntyre, T. M., Prescott, S. M. & Stafforini, D. M. The platelet-activating factor signaling system and its regulation in syndromes of inflammation and thrombosis. Crit. Care Med. 30, S294–S301 (2002).

Dhainaut, J.-F. A. et al. Platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist BN 52021 in the treatment of severe sepsis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 22, 1720–1728 (1994).

Froon, A. H. et al. Treatment with the platelet-activating factor antagonist TCV-309 in patients with severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a prospective, multi-center, double-blind, randomized phase II trial. Shock 5, 313–319 (1996).

Dhainaut, J. F. et al. Confirmatory platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist trial in patients with severe gram-negative bacterial sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Crit. Care Med. 26, 1963–1971 (1998).

Poeze, M., Froon, A. H., Ramsay, G., Buurman, W. A. & Greve, J. W. Decreased organ failure in patients with severe SIRS and septic shock treated with the platelet-activating factor antagonist TCV-309: a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase II trial. Shock 14, 421–428 (2000).

Suputtamongkol, Y. et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of an infusion of lexipafant (platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist) in patients with severe sepsis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 693–696 (2000).

Vincent, J. L., Spapen, H., Bakker, J., Webster, N. R. & Curtis, L. Phase II multicenter clinical study of the platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist BB-882 in the treatment of sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 28, 638–642 (2000).

Dhainaut, J.-F. A. et al. Platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist BN 52021 in the treatment of severe sepsis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 22, 1720–1728 (1994).

Kingsnorth, A. N., Galloway, S. W. & Formela, L. J. Randomized, double-blind phase II trial of Lexipafant, a platelet-activating factor antagonist, in human acute pancreatitis. Br. J. Surg. 82, 1414–1420 (1995).

Johnson, C. D. et al. Double blind, randomised, placebo controlled study of a platelet activating factor antagonist, lexipafant, in the treatment and prevention of organ failure in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. Gut 48, 62–69 (2001).

Tjoelker, L. W. et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of a platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Nature 374, 549–552 (1995).

Bernard, G. R. et al. The effects of ibuprofen on the physiology and survival of patients with sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 912–918 (1997).

Bernard, G. R. et al. Prostacyclin and thromboxane A2 formation is increased in human sepsis syndrome. Effects of cyclooxygenase inhibition. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis. 144, 1095–1101 (1991).

Haupt, M. T. et al. Effect of ibuprofen in patients with severe sepsis: A randomized, double blind, multicenter study. Crit. Care Med. 19, 1339–1347 (1991).

Grover, R. et al. An open-label dose escalation study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, N(G)-methyl-L-arginine hydrochloride (546C88), in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 27, 913–922 (1999).

Avontuur, J. A., Jongen-Lavrencic, M., van Amsterdam, J. G., Eggermont, A. M. & Bruining, H. A. Effect of L-NAME, an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis, on plasma levels of IL-6, IL-8, TNF α and nitrite/nitrate in human septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 24, 673–679 (1998).

Preiser, J. -C. et al. Methylene blue administration in septic shock: A clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 23, 259–264 (1995).

Andresen, M. et al. Blockade of the action of nitric oxide in human septic shock increases systemic vascular resistance and has detrimental effects on pulmonary function after a short infusion of methylene blue. J. Crit. Care 13, 164–168 (1998).

Hotchkiss, R. S. & Karl, I. E. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 238–250 (2003). Provides an excellent overview of current concepts of the pathogenesis and treatment of sepsis.

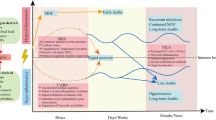

Bone, R. C. Sir Isaac Newton, sepsis, SIRS, and CARS. Crit. Care Med. 24, 1125–1128 (1996).

Docke, W. D. et al. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-γ treatment. Nature Med. 3, 678–681 (1997).

Kox, W. J. et al. Interferon γ-1b in the treatment of compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome. A new approach: proof of principle. Arch. Intern. Med. 157, 389–393 (1997).

Hershman, M. J., Appel, S. H., Wellhausen, S. R., Sonnenfeld, G. & Polk, H. C. Jr. Interferon-γ treatment increases HLA-DR expression on monocytes in severely injured patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 77, 67–70 (1989).

Nelson, S. & Bagby, G. J. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and modulation of inflammatory cells in sepsis. Clin. Chest Med. 17, 319–332 (1996).

Marshall, J. C. The effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) in pre-clinical models of infection and acute inflammation. Sepsis 2, 213–220 (1998).

Garcia-Carbonero, R. et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the treatment of high-risk febrile neutropenia: a multicenter randomized trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 93, 31–38 (2001).

Nelson, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of Filgrastim as an adjunct to antibiotics for treatment of hospitalized patients with community-acquired penumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 178, 1075–1080 (1998).

Nelson, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of filgrastim for the treatment of hospitalized patients with multilobar pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 182, 970–973 (2000).

Weiss, M., Gross-Weege, W., Harms, B. & Schneider, E. M. Filgrastim (RHG-CSF) related modulation of the inflammatory response in patients at risk of sepsis or with sepsis. Cytokine 8, 260–265 (1996).

Wunderink, R. G. et al. Filgrastim in patients with pneumonia and severe sepsis or septic shock. Chest 119, 523–529 (2001).

Root, R. K. et al. Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of filgrastim in patients hospitalized with pneumonia and severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 31, 367–373 (2003).

Gregory, S. A., Morrissey, J. H. & Edgington, T. S. Regulation of tissue factor gene expression in the monocyte procoagulant response to endotoxin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 2752–2755 (1989).

Esmon, C. T. Possible involvement of cytokines in diffuse intravascular coagulation and thrombosis. Baillieres Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 12, 343–359 (2000).

Dackiw, A. P. B., Nathens, A. B., Marshall, J. C. & Rotstein, O. D. Integrin engagement induces monocyte procoagulant activity and tumor necrosis factor production via induction of tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Surg. Res. 64, 210–215 (1996).

Esmon, C. The protein C pathway. Crit. Care Med. 28, S44–S48 (2000).

Smith, O. P. et al. Use of protein-C concentrate, heparin, and haemodiafiltration in meningococcus-induced purpura fulminans. Lancet 350, 1590–1593 (1997).

Ettingshausen, C. E., Veldmann, A., Schneider, W., Jager, G. & Kreuz, W. Replacement therapy with protein C concentrate in infants and adolescents with meningococcal sepsis and purpura fulminans. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 25, 537–541 (1999).

Ely, E. W. et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) administration across clinically important subgroups of patients with severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 31, 12–19 (2003).

Opal, S. M. Therapeutic rationale for antithrombin III in sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 28, S34–S37 (2000).

Ryu, J., Pyo, H., Jou, I. & Joe, E. Thrombin induces NO release from cultured rat microglia via protein kinase C, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and NFκB. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29955–29959 (2000).

Fourrier, F. et al. Septic shock, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Compared patterns of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S deficiencies. Chest 101, 816–823 (1992).

Eisele, B. et al. Antithrombin III in patients with severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 24, 663–672 (1998).

Warren, B. L. et al. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized, controlled trial. JAMA 286, 1869–1878 (2001).

Creasey, A. A. New potential therapeutic modalities: tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Sepsis 3, 173–182 (1999).

Abraham, E. Tissue factor inhibition and clinical trial results of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 28, S31–S33 (2000).

Jilma, B. et al. Pharmacodynamics of active site-inhibited factor VIIa in endotoxin-induced coagulation in humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 72, 403–410 (2002).

Davidson, B. L., Geerts, W. H. & Lensing, A. W. A. Low-dose heparin for severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1036–1037 (2002).

Meduri, G. U. An historical review of glucocorticoid treatment in sepsis. Disease pathophysiology and the design of treatment investigation. Sepsis 3, 21–38 (1999).

Rothwell, P. M., Udwadia, Z. F. & Lawler, P. G. Cortisol response to corticotropin and survival in septic shock. Lancet 337, 582–583 (1991).

Annane, D. et al. A 3-level prognostic classification in septic shock based on cortisol levels and cortisol response to corticotropin. JAMA 2834, 1038–1045 (2000).

Lamberts, S. W., Bruining, H. A. & de Jong, F. H. Corticosteroid therapy in severe illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 1285–1292 (1997).

Schumer, W. Steroids in the treatment of septic shock. Ann. Surg. 184, 333–341 (1976).

Sprung, C. L. et al. The effects of high-dose corticosteroids in patients with septic shock. A prospective, controlled study. N. Engl. J. Med. 311, 1137–1143 (1984).

Bone, R. C. et al. A controlled clinical trial of high dose methylprednisolone in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 317, 654–658 (1987). The first adequately powered multicentre trial of adjuvant therapy for sepsis, this paper introduced the concept of sepsis syndrome. In contrast to the later work of Annane et al . (reference 5), the authors found no evidence of benefit for exogenous glucocorticoid therapy in sepsis.

Hinshaw et al. & The Veterans Administration Systemic Sepsis Cooperative Study Group. Effect of high dose glucocorticoid therapy on mortality in patients with clinical signs of systemic sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 317, 659–665 (1987).

Cronin, L. et al. Corticosteroid treatment for sepsis: A critical appraisal and meta-analysis of the literature. Crit. Care Med. 23, 1430–1439 (1995).

Bollaert, P. E. et al. Reversal of late septic shock with supraphysiologic doses of hydrocortisone. Crit. Care Med. 26, 627–630 (1998).

Oppert, M. et al. Plasma cortisol levels before and during 'low-dose' hydrocortisone therapy and their relationship to hemodynamic improvement in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 26, 1747–1755 (2000).

Briegel, J., Jochum, M., Gippner-Steppert, C. & Thiel, M. Immunomodulation in septic shock: hydrocortisone differentially regulates cytokine responses. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12, S70–S74 (2001).

Keh, D. et al. Immunologic and hemodynamic effects of 'low-dose' hydrocortisone in septic shock. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 167, 512–520 (2003).

Fein, A. M. et al. Treatment of severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis with a novel bradykinin antagonist, deltibant (CP-0127): Results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. JAMA 277, 482–487 (1997).

Fronhoffs, S. et al. The effect of C1-esterase inhibitor in definite and suspected streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: report of seven patients. Crit. Care Med. 26, 1566–1570 (2000).

Caliezi, C. et al. C1-inhibitor in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: beneficial effect on renal dysfunction. Crit. Care Med. 30, 1722–1728 (2002).

Friedman, G. et al. Administration of an antibody to E-selectin in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 24, 229–233 (1996).

Rivers, E. et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1368–1377 (2001). A protocol of aggressive, goal-directed fluid resuscitation, initiated early in the emergency department, resulted in a 16% absolute reduction in subsequent mortality for patients with early sepsis.

Van den Berghe, G. et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the surgical intensive care unit. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1359–1367 (2001). Maintenance of blood glucose levels within essentially normal limits resulted in improved survival and reduced organ dysfunction in this single-centre Belgian study.

Leibovici, L. Effects of remote, retroactive intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients with bloodstream infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 323, 1450–1451 (2001).

Bone, R. C. Sepsis and controlled clinical trials: The odyssey. Crit. Care Med. 23, 1165–1166 (1995).

Fink, M. P. Another negative clinical trial of a new agent for the treatment of sepsis: rethinking the process of developing adjuvant treatments for serious infections. Crit. Care Med. 23, 989–991 (1995).

Cohen, J. et al. New strategies for clinical trials in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 29, 880–886 (2001).

Dellinger, R. P. et al. From the bench to the bedside: The future of sepsis research. Chest 111, 744–753 (1997).

Marshall, J. C. Clinical trials of mediator-directed therapy in sepsis: What have we learned? Intensive Care Med. 26, S75–S83 (2000).

Warren, H. S. et al. Assessment of ability of murine and human anti-lipid A monoclonal antibodies to bind and neutralize lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 177, 89–97 (1993).

Quezado, Z. M. et al. A controlled trial of HA-1A in a canine model of gram-negative septic shock. JAMA 269, 2221–2227 (1993).

Hinshaw, L. B. et al. Survival of primates in LD100 septic shock following therapy with antibody to tumor necrosis factor (TNF α). Circ. Shock 30, 279–292 (1990).

Gattinoni, L. et al. A trial of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 333, 1025–1032 (1995).

Bone, R. C. et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 101, 1644–1655 (1992). This manuscript, resulting from a North American consensus conference, introduced the concept of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and established contemporary consensus definitions of sepsis.

Bone, R. C. et al. Sepsis syndrome: a valid clinical entity. Crit. Care Med. 17, 389–393 (1989).

Vincent, J. L. Dear SIRS, I'm sorry to say that I don't like you. Crit. Care Med. 25, 372–374 (1997).

Marshall, J. C. Rethinking sepsis: from concepts to syndromes to diseases. Sepsis 3, 5–10 (1999).

Casey, L. C., Balk, R. A. & Bone, R. C. Plasma cytokines and endotoxin levels correlate with survival in patients with the sepsis syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 119, 771–778 (1993).

Abraham, E. & Marshall, J. C. Sepsis and mediator-directed therapy: Rethinking the target populations. Mol. Med. Today 5, 56–58 (1999).

Levy, M. M. et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit. Care Med. (In the press). Provides an updated international consensus perspective on definitions for sepsis, and argues the need for the development of a staging system for sepsis, as described in greater detail in reference 152.

Marshall, J. C. et al. Measures, markers, and mediators: Towards a staging system for clinical sepsis. Crit. Care Med. (In the press).

Sorenson, T. I., Nielsen, G. G., Andersen, P. K. & Teasdale, P. W. Genetic and environmental influences on premature death in adult adoptees. N. Engl. J. Med. 318, 727–732 (1988). This Scandinavian population-based study of adult adoptees established a strong genetic predisposition to early mortality from infection; the greater than fivefold increased risk is substantially larger than that seen for cardiovascular diseases or cancer.

Mira, J. -P. et al. Association of TNF2, a TNF-α promoter polymorphism, with septic shock susceptibility and mortality. JAMA 282, 561–568 (1999).

Appoloni, O. et al. Association of tumor necrosis factor-2 allele with plasma tumor necrosis factor-α levels and mortality from septic shock. Am. J. Med. 110, 486–488 (2001).

Marshall, J. C. et al. Multiple organ dysfunction score: A reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit. Care Med. 23, 1638–1652 (1995). This paper describes the methodological development and validation of the first contemporary score for organ dysfunction in critical illness; the MOD score and the SOFA score (reference 157) have been used as measures of organ dysfunction in a number of trials of novel therapies for sepsis.

Vincent, J. -L. et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 22, 707–710 (1996).

Marshall, J. C., Panacek, E. A., Teoh, L. & Barchuk, W. Modelling organ dysfunction as a risk factor, outcome, and measure of biologic effect in sepsis: Results of the MONARCS trial. Crit. Care Med. 28, A46 (2001).

Petros, A. J., Marshall, J. C. & van Saene, H. K. F. Should morbidity replace mortality as an endpoint for clinical trials in intensive care? Lancet 345, 369–371 (1995).

Marshall, J. C. Charting the course of critical illness: Prognostication and outcome description in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 27, 676–678 (1999).

Grover, R. et al. Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: Effect on survival in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 27, A33 (1999).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Glossary

- MENINOGOCOCCAEMIA

-

An uncommon, but fulminant, infection with substantial mortality and morbidity in the form of tissue necrosis leading to the loss of digits and even limbs.

- APACHE II SCORES

-

A composite measure of acute severity of illness, including variables reflecting acute (A) physiology (P), age (A) and chronic health evaluation (CHE).

- ISOFORMS OF NOS

-

Constitutively expressed nitric oxide synthase is present in endothelial cells, neurons, and hepatocytes. An inducible form of the enzyme is also present in cells of the innate immune system; its expression is upregulated by endotoxin and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

- ZYMOGEN

-

A proenzyme. Requires enzymatic activation to exert its own effects.

- TNM STRATIFICATION SYSTEM

-

The TNM (tumours, nodes, metastasis) system, widely used in cancer clinical trials, characterizes patients by variables that not only correlate with prognosis, but also reflect a differential potential of response to therapy.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marshall, J. Such stuff as dreams are made on: mediator-directed therapy in sepsis. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2, 391–405 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1084

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1084

This article is cited by

-

RETRACTED ARTICLE: The Role of Vitamin C in the Treatment of Sepsis

Drugs & Therapy Perspectives (2022)

-

Synergistic cytoprotection by co-treatment with dexamethasone and rapamycin against proinflammatory cytokine-induced alveolar epithelial cell injury

Journal of Intensive Care (2019)

-

Nonhuman primate species as models of human bacterial sepsis

Lab Animal (2019)

-

Whole-organism phenotypic screening for anti-infectives promoting host health

Nature Chemical Biology (2018)

-

Protective Effects of Nobiletin Against Endotoxic Shock in Mice Through Inhibiting TNF-α, IL-6, and HMGB1 and Regulating NF-κB Pathway

Inflammation (2016)