Key Points

-

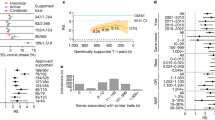

Mendelian randomization uses genetic variants to test the causality of a relationship between an exposure and an outcome

-

Mendelian randomization is not affected by the confounding inherent in observational studies but it does rely on several assumptions, which can be hard to test

-

Mendelian randomization can provide a cost-effective substitute for clinical trials that would be expensive, or logistically or ethically challenging

-

In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Mendelian randomization has provided evidence for a protective effect of IL-1 receptor antagonism, and for relationships between vitamin D status, disease outcome and response to therapy

-

Mendelian randomization can provide evidence that relationships suggested by observation are not causal; for example, it suggests IgG N-glycosylation is a biomarker of RA rather than an agent of disease

Abstract

Establishing causality of risk factors is important to determine the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying rheumatic diseases, and can facilitate the design of interventions to improve care for affected patients. The presence of unmeasured confounders, as well as reverse causation, is a challenge to the assignment of causality in observational studies. Alleles for genetic variants are randomly inherited at meiosis. Mendelian randomization analysis uses these genetic variants to test whether a particular risk factor is causal for a disease outcome. In this Review of the Mendelian randomization technique, we discuss published results and potential applications in rheumatology, as well as the general clinical utility and limitations of the approach.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

22 February 2017

In the originally published version of the above Review, in the left-hand panel of Figure 2b the residuals were represented by horizontal rather than vertical double-headed arrows between the individual data points and the regression line, and in the right-hand panel the labels for the axes were inverted; in the legend for Figure 2b and on page 487 of the article where Figure 2 is cited, the description of the two-stage least squares method was inaccurate; and owing to an editorial oversight, a sentence on page 488 mistakenly referred to the occurrence of “reverse causality” instead of “inverse causality”. These errors have been corrected in the online version of the article. Also, in the discussion of the Wald method on page 488, the sentence “However, estimating the effect size of an exposure on the outcome is not possible” has been deleted to avoid ambiguity.

References

Di Giuseppe, D., Discacciata, A., Orsini, N. & Wolk, A. Cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, R61 (2014).

Singh, J. A., Reddy, S. G. & Kundukulam, J. Risk factors for gout and prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 23, 192–202 (2011).

Campion, E. W., Glynn, R. J. & DeLabry, L. O. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks Consequences Normative Aging Study. Am. J. Med. 82, 421–426 (1987).

Batt, C. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: a risk factor for prevalent gout with SLC2A9 genotype-specific effects on serum urate and risk of gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 2101–2106 (2014).

Vartanian, L. R., Schwartz, M. B. & Brownell, K. D. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Pub. Health. 97, 667–675 (2007).

Choi, J. W., Ford, E. S., Gao, X. & Choi, H. K. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 59, 109–116 (2008).

Smith, G. D. & Ebrahim, S. 'Mendelian randomization': can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int. J. Epidemiol. 32, 1–22 (2003).

Davey Smith, G. & Ebrahim, S. What can mendelian randomisation tell us about modifiable behavioural and environmental exposures? BMJ 330, 1076–1079 (2005).

Berry, D. J., Vimaleswaran, K. S., Whittaker, J. C., Hingorani, A. D. & Hyppönen, E. Evaluation of genetic markers as instruments for Mendelian randomization studies on vitamin D. PLoS ONE 7, e37465 (2012).

Boef, A. G., Dekkers, O. M. & le Cessie, S. Mendelian randomization studies: a review of the approaches used and the quality of reporting. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 496–511 (2015).

Kang, D. H. & Chen, W. Uric acid and chronic kidney disease: new understanding of an old problem. Semin. Nephrol. 31, 447–452 (2011).

Krishnan, E. Reduced glomerular function and prevalence of gout: NHANES 2009–10. PLoS ONE 7, e50046 (2012).

Weiner, D. E. et al. Uric acid and incident kidney disease in the community. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 1204–1211 (2008).

Pierce, B. L., Ahsan, H. & VanderWeele, T. J. Power and instrument strength requirements for Mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 740–752 (2011).

VanderWeele, T. J., Tchetgen Tchetgen, E. J., Cornelis, M. & Kraft, P. Methodological challenges in Mendelian randomization. Epidemiology 25, 427–435 (2014).

Baum, C. F., Schaffer, M. E. & Stillman, S. Instrumental variables and GMM: estimation and testing. Stata J. 3, 1–31 (2003).

Hausman, J. A. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica 46, 1251–1271 (1978).

Burgess, S., Dudbridge, F. & Thompson, S. G. Combining information on multiple instrumental variables in Mendelian randomization: comparison of allele score and summarized data methods. Stat. Med. 35, 1880–1906 (2016).

Burgess, S. & Thompson, S. G. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 755–764 (2011).

Hughes, K., Flynn, T., de Zoysa, J., Dalbeth, N. & Merriman, T. R. Mendelian randomization analysis associates increased serum urate, due to genetic variation in uric acid transporters, with improved renal function. Kidney Int. 85, 344–351 (2014).

Davey Smith, G. & Ebrahim, S. in Biosocial Surveys: Current Insight and Future Promise (eds Vaupal, J. W., Weinstein, M. & Wachter, K. W.) 336–366 (The National Academies Press, 2008).

Burgess, S. Sample size and power calculations in Mendelian randomization with a single instrumental variable and a binary outcome. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 922–929 (2014).

Evans, D. M. & Davey Smith, G. Mendelian randomization: new applications in the coming age of hypothesis-free causality. Ann. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 16, 327–350 (2015).

Lawlor, D. A., Harbord, R. M., Sterne, J. A., Timpson, N. & Davey Smith, G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat. Med. 27, 1133–1163 (2008).

Palmer, T. M. et al. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 21, 223–242 (2012).

Kottgen, A. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat. Genet. 45, 145–154 (2013).

Köttgen, A. et al. New loci associated with kidney function and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 42, 376–384 (2010).

Orho-Melander, M. et al. Common missense variant in the glucokinase regulatory protein gene is associated with increased plasma triglyceride and C-reactive protein but lower fasting glucose concentrations. Diabetes 57, 3112–3121 (2008).

Phipps-Green, A. J. et al. Twenty-eight loci that influence serum urate levels: analysis of association with gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 124–130 (2016).

Viatte, S. et al. The role of genetic polymorphisms regulating vitamin D levels in rheumatoid arthritis outcome: a Mendelian randomisation approach. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 1430–1433 (2014).

Yarwood, A. et al. Testing the role of vitamin D in response to antitumour necrosis factor α therapy in a UK cohort: a Mendelian randomisation approach. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 938–940 (2014).

Parekh, R. B. et al. Association of rheumatoid arthritis and primary osteoarthritis with changes in the glycosylation pattern of total serum IgG. Nature 316, 452–457 (1985).

Yarwood, A. et al. Loci associated with N-glycosylation of human IgG are not associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a Mendelian randomisation study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 317–320 (2016).

Lauc, G. et al. Loci associated with N-glycosylation of human immunoglobulin G show pleiotropy with autoimmune diseases and haematological cancers. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003225 (2013).

Interleukin 1 Genetics Consortium. Cardiometabolic effects of genetic upregulation of the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3, 243–253 (2015).

Calvo, M. S. The effects of high phosphorous intake on calcium homeostasis. Adv. Nutr. Res. 9, 183–207 (1994).

Pekkinen, M. et al. FGF23 gene variation and its association with phosphate homeostasis and bone mineral density in Finnish children and adolescents. Bone 71, 124–130 (2015).

Keenan, T. et al. Causal assessment of serum urate levels in cardiometabolic diseases through a Mendelian randomization study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 407–416 (2016).

White, J. et al. Plasma urate concentration and risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 4, 327–336 (2016).

Burgess, S., Daniel, R. M., Butterworth, A. S. & Thompson, S. G. Network Mendelian randomization: using genetic variants as instrumental variables to investigate mediation in causal pathways. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 484–495 (2015).

Lyngdoh, T. et al. Serum uric acid and adiposity: deciphering causality using a bidirectional Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS ONE 7, e39321 (2012).

Oikonen, M. et al. Associations between serum uric acid and markers of subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults. The cardiovascular risk in Young Finns study. Atherosclerosis 223, 497–503 (2012).

Palmer, T. M. et al. Association of plasma uric acid with ischaemic heart disease and blood pressure: mendelian randomisation analysis of two large cohorts. BMJ 347, f4262 (2013).

Rasheed, H., Hughes, K., Flynn, T. J. & Merriman, T. R. Mendelian randomization provides no evidence for a causal role of serum urate in increasing serum triglyceride levels. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 7, 830–837 (2014).

Johnson, R. J., Merriman, T. & Lanaspa, M. A. Causal or noncausal relationship of uric acid with diabetes. Diabetes 64, 2720–2722 (2015).

Merriman, T. R. An update on the genetic architecture of hyperuricemia and gout. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 98 (2015).

Dehghan, A. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. 123, 731–738 (2011).

Ellis, J. et al. Large multiethnic candidate gene study for C-reactive protein levels: identification of a novel association at CD36 in African Americans. Hum. Genet. 133, 985–995 (2014).

Ganesh, S. K. et al. Loci influencing blood pressure identified using a cardiovascular gene-centric array. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 1663–1678 (2013).

Baker, J. F. et al. Weight loss, the obesity paradox, and the risk of death in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 1711–1717 (2015).

McCaffery, J. M. et al. Human cardiovascular disease IBC chip-wide association with weight loss and weight regain in the look AHEAD trial. Hum. Hered. 75, 160–174 (2013).

IL6R Genetics Consortium Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration et al. Interleukin-6 receptor pathways in coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 82 studies. Lancet 379, 1205–1213 (2012).

Interleukin-6 Receptor Mendelian Randomisation Analysis (IL6R MR) Consortium. The interleukin-6 receptor as a target for prevention of coronary heart disease: a mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet 379, 1214–1224 (2012).

Goicoechea, M. et al. Allopurinol and progression of CKD and cardiovascular events: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 65, 543–549 (2015).

Spitsin, S., Hooper, D. C., Mikheeva, T. & Koprowski, H. Uric acid levels in patients with multiple sclerosis: analysis in mono- and dizygotic twins. Mult. Scler. 7, 165–166 (2001).

Euser, S. M., Hofman, A., Westendorp, R. G. & Breteler, M. M. Serum uric acid and cognitive function and dementia. Brain 132, 377–382 (2009).

Schretlen, D. J. et al. Serum uric acid and cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults. Neuropsychology 21, 136–140 (2007).

Di Giuseppe, D., Alfredsson, L., Bottai, M., Askling, J. & Wolk, A. Long term alcohol intake and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women: a population based cohort study. BMJ 345, e4230 (2012).

Palmer, R. H. et al. Shared additive genetic influences on DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence in subjects of European ancestry. Addiction 110, 1922–1931 (2015).

Fini, M. A., Elias, A., Johnson, R. J. & Wright, R. M. Contribution of uric acid to cancer risk, recurrence, and mortality. Clin. Transl. Med. 1, 16 (2012).

Ames, B. N., Cathcart, R., Schwiers, E. & Hochstein, P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 78, 6858–6862 (1981).

Sautin, Y. Y. & Johnson, R. J. Uric acid: the oxidant-antioxidant paradox. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 27, 608–619 (2008).

Levine, W., Dyer, A. R., Shekelle, R. B., Schoenberger, J. A. & Stamler, J. Serum uric acid and 11.5-year mortality of middle-aged women: findings of the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 42, 257–267 (1989).

Takkunen, H., Reunanen, A., Aromaa, A. & Knekt, P. Raised serum urate concentration as risk factor for premature mortality in middle aged men. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 288, 1161 (1984).

Kolonel, L. N., Yoshizawa, C., Nomura, A. M. & Stemmermann, G. N. Relationship of serum uric acid to cancer occurrence in a prospective male cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 3, 225–228 (1994).

Hiatt, R. A. & Fireman, B. H. Serum uric acid unrelated to cancer incidence in humans. Cancer Res. 48, 2916–2918 (1988).

Petersson, B. & Trell, E. Raised serum urate concentration as risk factor for premature mortality in middle aged men: relation to death from cancer. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 287, 7–9 (1983).

Ghaemi-Oskouie, F. & Shi, Y. The role of uric acid as an endogenous danger signal in immunity and inflammation. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 13, 160–166 (2011).

Ghiringhelli, F. et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1β–dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat. Med. 15, 1170–1178 (2009).

Boffetta, P., Nordenvall, C., Nyrén, O. & Ye, W. A prospective study of gout and cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 18, 127–132 (2009).

Doody, M. M. et al. Leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma following selected medical conditions. Cancer Causes Control 3, 449–456 (1992).

Kuo, C. F. et al. Increased risk of cancer among gout patients: a nationwide population study. Joint Bone Spine 79, 375–378 (2012).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A., Malarstig, A. & Thompson, S. G. Use of Mendelian randomisation to assess potential benefit of clinical intervention. BMJ 345, e7325 (2012).

Antonopoulos, A. S., Margaritis, M., Lee, R., Channon, K. & Antoniades, C. Statins as anti-inflammatory agents in atherogenesis: molecular mechanisms and lessons from the recent clinical trials. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18, 1519–1530 (2012).

Ference, B. A. et al. Effect of long-term exposure to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol beginning early in life on the risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomization analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, 2631–2639 (2012).

Schooling, C. M., Freeman, G. & Cowling, B. J. Mendelian randomization and estimation of treatment efficacy for chronic diseases. Am. J. Epidemiol. 177, 1128–1133 (2013).

Sofat, R. et al. Separating the mechanism-based and off-target actions of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors with CETP gene polymorphisms. Circulation 121, 52–62 (2010).

Aulchenko, Y. S. et al. Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat. Genet. 41, 47–55 (2009).

Sluijs, I. et al. A Mendelian randomization study of circulating uric acid and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 64, 3028–3036 (2015).

Dupuis, J. et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat. Genet. 42, 105–116 (2010).

Thanassoulis, G. & O'Donnell, C. J. Mendelian randomization: nature's randomized trial in the post-genome era. JAMA 301, 2386–2388 (2009).

Bao, Y. et al. Lack of gene-diuretic interactions on the risk of incident gout: the Nurses' Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1394–1398 (2015).

McAdams-DeMarco, M. A. et al. A urate gene-by-diuretic interaction and gout risk in participants with hypertension: results from the ARIC study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 701–706 (2013).

Katan, M. B. Apolipoprotein E isoforms, serum cholesterol, and cancer. Lancet 327, 507–508 (1986).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol. 37, 658–665 (2013).

Voight, B. F. et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet 380, 572–580 (2012).

Haase, C. L. et al. LCAT, HDL cholesterol and ischemic cardiovascular disease: a Mendelian randomization study of HDL cholesterol in 54,500 individuals. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E248–E256 (2012).

Burgess, S., Freitag, D. F., Khan, H., Gorman, D. N. & Thompson, S. G. Using multivariable Mendelian randomization to disentangle the causal effects of lipid fractions. PLoS ONE 9, e108891 (2014).

Barter, P. J. et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2109–2122 (2007).

Cannon, C. P. et al. Safety of anacetrapib in patients with or at high risk for coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 2406–2415 (2010).

Schwartz, G. G. et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2089–2099 (2012).

Boden, W. E. et al. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 2255–2267 (2011).

Ford, E. S. et al. Homocyst(e)ine and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the evidence with special emphasis on case-control studies and nested case-control studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 31, 59–70 (2002).

Klerk, M. et al. MTHFR 677C→T polymorphism and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA 288, 2023–2031 (2002).

Frederiksen, J. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism (C677T), hyperhomocysteinemia, and risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism: prospective and case-control studies from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Blood 104, 3046–3051 (2004).

Gordon, T., Castelli, W. P., Hjortland, M. C., Kannel, W. B. & Dawber, T. R. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am. J. Med. 62, 707–714 (1977).

Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration et al. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet 375, 132–140 (2010).

C Reactive Protein Coronary Heart Disease Genetics Collaboration (CCGC) et al. Association between C reactive protein and coronary heart disease: mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ 342, d548 (2011).

O'Leary, C. M. & Bower, C. Guidelines for pregnancy: what's an acceptable risk, and how is the evidence (finally) shaping up? Drug Alcohol Rev. 31, 170–183 (2012).

Zuccolo, L. et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure and offspring cognition and school performance. A 'Mendelian randomization' natural experiment. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 1358–1370 (2013).

Moore, R. D., Levine, D. M., Southard, J., Entwisle, G. & Shapiro, S. Alcohol consumption and blood pressure in the 1982 Maryland Hypertension Survey. Am. J. Hypertens. 3, 1–7 (1990).

Fuchs, F. D., Chambless, L. E., Whelton, P. K., Nieto, F. J. & Heiss, G. Alcohol consumption and the incidence of hypertension: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Hypertension 37, 1242–1250 (2001).

Patel, R. et al. The detection, treatment and control of high blood pressure in older British adults: cross-sectional findings from the British Women's Heart and Health Study and the British Regional Heart Study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 20, 733–741 (2006).

Marmot, M. G. et al. Alcohol and blood pressure: the INTERSALT study. BMJ 308, 1263–1267 (1994).

Chen, L., Smith, G. D., Harbord, R. M. & Lewis, S. J. Alcohol intake and blood pressure: a systematic review implementing a Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS Med. 5, e52 (2008).

Liel, Y., Ulmer, E., Shary, J., Hollis, B. W. & Bell, N. H. Low circulating vitamin D in obesity. Calcif. Tissue Int. 43, 199–201 (1988).

Sneve, M., Figenschau, Y. & Jorde, R. Supplementation with cholecalciferol does not result in weight reduction in overweight and obese subjects. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 159, 675–684 (2008).

Zittermann, A. et al. Vitamin D supplementation enhances the beneficial effects of weight loss on cardiovascular disease risk markers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 1321–1327 (2009).

Salehpour, A. et al. Vitamin D3 and the risk of CVD in overweight and obese women: a randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 108, 1866–1873 (2012).

Vimaleswaran, K. S. et al. Causal relationship between obesity and vitamin D status: bi-directional Mendelian randomization analysis of multiple cohorts. PLoS Med. 10, e1001383 (2013).

Mora, S. et al. Lipoprotein(a) and risk of type 2 diabetes. Clin. Chem. 56, 1252–1260 (2010).

Ye, Z. et al. The association between circulating lipoprotein(a) and type 2 diabetes: is it causal? Diabetes 63, 332–342 (2014).

Leong, A. et al. The causal effect of vitamin D binding protein (DBP) levels on calcemic and cardiometabolic diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 11, e1001751 (2014).

Palmer, T. M., Thompson, J. R. & Tobin, M. D. Meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies incorporating all three genotypes. Stat. Med. 27, 6570–6582 (2008).

Mann, V. et al. A COL1A1 Sp1 binding site polymorphism predisposes to osteoporotic fracture by affecting bone density and quality. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 899–907 (2001).

Panoutsopoulou, K. et al. The effect of FTO variation on increased osteoarthritis risk is mediated through body mass index: a mendelian randomisation study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 2082–2086 (2014).

Pfister, R. et al. No evidence for a causal link between uric acid and type 2 diabetes: a Mendelian randomisation approach. Diabetologia 54, 2561–2569 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.R. and T.R.M. researched data for the article and wrote the manuscript. P.R., H.K.C. and T.R.M. contributed substantially to discussions of the article content. R.D. undertook review and editing of the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.R. declares that he has received speaking and consulting fees from Menarini and speaking fees and research funding from AstraZeneca. T.R.M. declares that he has received consulting fees and research funding from Ardea Biosciences and AstraZeneca. H.K.C. declares that he has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Takeda. R.D. declares no competing interests.

Related links

DATABASES

FURTHER INFORMATION

Supplementary information

Supplementary information S1 (table)

Systematic literature review* of Mendelian randomization studies of urate (PDF 723 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robinson, P., Choi, H., Do, R. et al. Insight into rheumatological cause and effect through the use of Mendelian randomization. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12, 486–496 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.102

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.102

This article is cited by

-

Effects of elevated serum urate on cardiometabolic and kidney function markers in a randomised clinical trial of inosine supplementation

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Longitudinal development of incident gout from low-normal baseline serum urate concentrations: individual participant data analysis

BMC Rheumatology (2021)

-

Genetic correlations between traits associated with hyperuricemia, gout, and comorbidities

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

-

Evaluating marginal genetic correlation of associated loci for complex diseases and traits between European and East Asian populations

Human Genetics (2021)

-

Overlapping-sample Mendelian randomisation with multiple exposures: a Bayesian approach

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2020)