Abstract

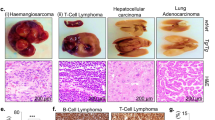

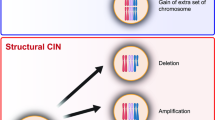

Cell cycle genes are often aberrantly expressed in cancer, but how their misexpression drives tumorigenesis mostly remains unclear. From S phase to early mitosis, EMI1 (also known as FBXO5) inhibits the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome, which controls cell cycle progression through the sequential degradation of various substrates. By analyzing 7403 human tumor samples, we find that EMI1 overexpression is widespread in solid tumors but not in blood cancers. In solid cancers, EMI1 overexpression is a strong prognostic marker for poor patient outcome. To investigate causality, we generated a transgenic mouse model in which we overexpressed Emi1. Emi1-overexpressing animals develop a wide variety of solid tumors, in particular adenomas and carcinomas with inflammation and lymphocyte infiltration, but not blood cancers. These tumors are significantly larger and more penetrant, abundant, proliferative and metastatic than control tumors. In addition, they are highly aneuploid with tumor cells frequently being in early mitosis and showing mitotic abnormalities, including lagging and incorrectly segregating chromosomes. We further demonstrate in vitro that even though EMI1 overexpression may cause mitotic arrest and cell death, it also promotes chromosome instability (CIN) following delayed chromosome alignment and anaphase onset. In human solid tumors, EMI1 is co-expressed with many markers for CIN and EMI1 overexpression is a stronger marker for CIN than most well-established ones. The fact that Emi1 overexpression promotes CIN and the formation of solid cancers in vivo indicates that Emi1 overexpression actively drives solid tumorigenesis. These novel mechanistic insights have important clinical implications.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 50 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $5.18 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Malumbres M, Barbacid M . Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 153–166.

Teixeira LK, Reed SI . Ubiquitin ligases and cell cycle control. Annu Rev Biochem 2013; 82: 387–414.

Frye JJ, Brown NG, Petzold G, Watson ER, Grace CR, Nourse A et al. Electron microscopy structure of human APC/C(CDH1)-EMI1 reveals multimodal mechanism of E3 ligase shutdown. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013; 20: 827–835.

Wang W, Kirschner MW . Emi1 preferentially inhibits ubiquitin chain elongation by the anaphase-promoting complex. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15: 797–806.

Miller JJ, Summers MK, Hansen DV, Nachury MV, Lehman NL, Loktev A et al. Emi1 stably binds and inhibits the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome as a pseudosubstrate inhibitor. Genes Dev 2006; 20: 2410–2420.

Di Fiore B, Pines J . Emi1 is needed to couple DNA replication with mitosis but does not regulate activation of the mitotic APC/C. J Cell Biol 2007; 177: 425–437.

Perez de Castro I, de Carcer G, Malumbres M . A census of mitotic cancer genes: new insights into tumor cell biology and cancer therapy. Carcinogenesis 2007; 28: 899–912.

Lehman NL, Tibshirani R, Hsu JY, Natkunam Y, Harris BT, West RB et al. Oncogenic regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome are frequently overexpressed in malignant tumors. Am J Pathol 2007; 170: 1793–1805.

Holland AJ, Cleveland DW . Losing balance: the origin and impact of aneuploidy in cancer. EMBO Rep 2012; 13: 501–514.

Ricke RM, van Deursen JM . Aneuploidy in health, disease, and aging. J Cell Biol 2013; 201: 11–21.

Foijer F, Draviam VM, Sorger PK . Studying chromosome instability in the mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008; 1786: 73–82.

Pfau SJ, Amon A . Chromosomal instability and aneuploidy in cancer: from yeast to man. EMBO Rep 2012; 13: 515–527.

Duijf PH, Benezra R . The cancer biology of whole-chromosome instability. Oncogene 2013; 32: 4727–4736.

Duijf PH, Schultz N, Benezra R . Cancer cells preferentially lose small chromosomes. Int J Cancer 2013; 132: 2316–2326.

Hsu JY, Reimann JD, Sorensen CS, Lukas J, Jackson PK . E2F-dependent accumulation of hEmi1 regulates S phase entry by inhibiting APC(Cdh1). Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4: 358–366.

Machida YJ, Dutta A . The APC/C inhibitor, Emi1, is essential for prevention of rereplication. Genes Dev 2007; 21: 184–194.

Neelsen KJ, Zanini IM, Mijic S, Herrador R, Zellweger R, Ray Chaudhuri A et al. Deregulated origin licensing leads to chromosomal breaks by rereplication of a gapped DNA template. Genes Dev 2013; 27: 2537–2542.

Lee H, Lee DJ, Oh SP, Park HD, Nam HH, Kim JM et al. Mouse emi1 has an essential function in mitotic progression during early embryogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 5373–5381.

Robu ME, Zhang Y, Rhodes J . Rereplication in emi1-deficient zebrafish embryos occurs through a Cdh1-mediated pathway. PLoS One 2012; 7: e47658.

Verschuren EW, Ban KH, Masek MA, Lehman NL, Jackson PK . Loss of Emi1-dependent anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome inhibition deregulates E2F target expression and elicits DNA damage-induced senescence. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27: 7955–7965.

Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, Varambally R, Yu J, Briggs BB et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18 000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia 2007; 9: 166–180.

Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012; 490: 61–70.

Harris TJ, McCormick F . The molecular pathology of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010; 7: 251–265.

Galea MH, Blamey RW, Elston CE, Ellis IO . The Nottingham Prognostic Index in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1992; 22: 207–219.

Ravdin PM, Siminoff LA, Davis GJ, Mercer MB, Hewlett J, Gerson N et al. Computer program to assist in making decisions about adjuvant therapy for women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 980–991.

Dexter TJ, Sims D, Mitsopoulos C, Mackay A, Grigoriadis A, Ahmad AS et al. Genomic distance entrained clustering and regression modelling highlights interacting genomic regions contributing to proliferation in breast cancer. BMC Syst Biol 2010; 4: 127.

Kistner A, Gossen M, Zimmermann F, Jerecic J, Ullmer C, Lubbert H et al. Doxycycline-mediated quantitative and tissue-specific control of gene expression in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 10933–10938.

Carter SL, Eklund AC, Kohane IS, Harris LN, Szallasi Z . A signature of chromosomal instability inferred from gene expression profiles predicts clinical outcome in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 1043–1048.

Birkbak NJ, Eklund AC, Li Q, McClelland SE, Endesfelder D, Tan P et al. Paradoxical relationship between chromosomal instability and survival outcome in cancer. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 3447–3452.

Swanton C, Nicke B, Schuett M, Eklund AC, Ng C, Li Q et al. Chromosomal instability determines taxane response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 8671–8676.

Schvartzman JM, Duijf PH, Sotillo R, Coker C, Benezra R . Mad2 Is a Critical Mediator of the Chromosome Instability Observed upon Rb and p53 Pathway Inhibition. Cancer Cell 2011; 19: 701–714.

Burkhart DL, Sage J . Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer 2008; 8: 671–682.

Malumbres M . Oncogene-induced mitotic stress: p53 and pRb get mad too. Cancer Cell 2011; 19: 691–692.

Manning AL, Benes C, Dyson NJ . Whole chromosome instability resulting from the synergistic effects of pRB and p53 inactivation. Oncogene 2014; 33: 2487–2494.

Sotillo R, Schvartzman JM, Socci ND, Benezra R . Mad2-induced chromosome instability leads to lung tumour relapse after oncogene withdrawal. Nature 2010; 464: 436–440.

Margottin-Goguet F, Hsu JY, Loktev A, Hsieh HM, Reimann JD, Jackson PK . Prophase destruction of Emi1 by the SCF(betaTrCP/Slimb) ubiquitin ligase activates the anaphase promoting complex to allow progression beyond prometaphase. Dev Cell 2003; 4: 813–826.

Janssen A, Kops GJ, Medema RH . Elevating the frequency of chromosome mis-segregation as a strategy to kill tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 19108–19113.

Weaver BA, Cleveland DW . Aneuploidy: instigator and inhibitor of tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 10103–10105.

Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012; 487: 330–337.

Cancer Genome Atlas N. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011; 474: 609–615.

Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 2013; 499: 43–49.

Cancer Genome Atlas N Cancer Genome Atlas N Kandoth C Cancer Genome Atlas N Schultz N Cancer Genome Atlas N Cherniack AD Cancer Genome Atlas N Akbani R Cancer Genome Atlas N Liu Y et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013; 497: 67–73.

Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 511: 1–7.

Gyorffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lanczky A . Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One 2013; 8: e82241.

Detre S, Saclani Jotti G, Dowsett M . A "quickscore" method for immunohistochemical semiquantitation: validation for oestrogen receptor in breast carcinomas. J Clin Pathol 1995; 48: 876–878.

Russell PJ, Raghavan D, Gregory P, Philips J, Wills EJ, Jelbart M et al. Bladder cancer xenografts: a model of tumor cell heterogeneity. Cancer Res 1986; 46: 2035–2040.

Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 2008; 455: 1061–1068.

Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips HS, Pujara K, Berman BP et al. Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer Cell 2010; 17: 510–522.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert Benezra for support, Kym French for animal husbandry, Andrew Brooks for plasmids, Sandrine Roy, Ali Ju, Loredana Spoerri, Yvette Chin and Nicole Chee for technical assistance, Kim-Anh Lê Cao for statistical advice, Marianna Datseris for general support and Pulari Thangavelu and Mehlika Hazar-Rethinam for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by IPRS and University of Queensland (UQ) Centennial Scholarships (to SV), grants from UQ Diamantina Institute and UQ and a Career Development Fellowship from the National Breast Cancer Foundation (to PHGD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Oncogene website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vaidyanathan, S., Cato, K., Tang, L. et al. In vivo overexpression of Emi1 promotes chromosome instability and tumorigenesis. Oncogene 35, 5446–5455 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2016.94

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2016.94

This article is cited by

-

Effect of Emi1 gene silencing on the proliferation and invasion of human breast cancer cells

BMC Molecular and Cell Biology (2023)

-

Alpha-B-Crystallin overexpression is sufficient to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis in mice

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2023)

-

FBXL2 promotes E47 protein instability to inhibit breast cancer stemness and paclitaxel resistance

Oncogene (2023)

-

SAPCD2 promotes neuroblastoma progression by altering the subcellular distribution of E2F7

Cell Death & Disease (2022)

-

circEVI5 acts as a miR-4793-3p sponge to suppress the proliferation of gastric cancer

Cell Death & Disease (2021)