Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer are leading causes of death with comparable symptoms at the end of life. Cross-national comparisons of place of death, as an important outcome of terminal care, between people dying from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer have not been studied before. We collected population death certificate data from 14 countries (year: 2008), covering place of death, underlying cause of death, and demographic information. We included patients dying from lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and used descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regressions to describe patterns in place of death. Of 5,568,827 deaths, 5.8% were from lung cancer and 4.4% from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Among lung cancer decedents, home deaths ranged from 12.5% in South Korea to 57.1% in Mexico, while hospital deaths ranged from 27.5% in New Zealand to 77.4% in France. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, the proportion dying at home ranged from 10.4% in Canada to 55.4% in Mexico, while hospital deaths ranged from 41.8% in Mexico to 78.9% in South Korea. Controlling for age, sex, and marital status, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were significantly less likely die at home rather than in hospital in nine countries. Our study found in almost all countries that those dying from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as compared with those from lung cancer are less likely to die at home and at a palliative care institution and more likely to die in a hospital or a nursing home. This might be due to less predictable disease trajectories and prognosis of death in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are two major causes of death in many countries, appearing as the fifth and third most common cause of death globally.1 Both illnesses affect patients’ quality of life with various stages of functional decline before death. Studies suggested that patients from both disease groups suffer from considerable dyspnea and pain.2,3,4 Other studies have indicated that people with COPD have severe symptoms causing major disruptions to normal life but these are often perceived and accepted as a “way of life” rather than an illness.5, 6 Despite similar problems, existing literature has reported a disadvantage for people with COPD compared with those with lung cancer in receiving end-of-life care.3, 4, 7, 8 Lung cancer patients seem to receive a more holistic palliative approach to care.3 Fewer palliative care resources were used by people with COPD3, 4, 9, 10 and end-of-life care discussions occurred later in their disease trajectories.11 Those with COPD also seem to face unmet care needs to a larger extent12, 13 and appear to have less access to palliative care services.9, 14 The historical focus of palliative care on cancer patients may be one reason for this.7 Another reason might be the difference in disease trajectories.15 Predicting outcomes or prognosis is often easier for patients with lung cancer with a rapid decline and a distinct terminal phase than for those with COPD who have more acute exacerbations and have less recognizable terminal phase.16

Previous research comparing end-of-life care for COPD and lung cancer patients has focused on symptom management17,18,19 and communication,14, 20, 21 little is known about how place of death differs between them. Place of death is often seen as a contributing factor in quality of dying, particularly because most people prefer to be cared for and to die at home.22, 23 The setting of dying has been shown to influence the characteristics of care and the dying experience. From research using Medicare data from the United States (USA), we know that COPD patients were more likely to die in hospital than were lung cancer patients.24 Nonetheless, cross-national comparisons for both populations remain scarce and such studies encourage mutual learning across borders by shedding a light on how patients with the same or different diseases die in different countries. Even neighboring countries with relatively similar cultures may organize end-of-life care differently and this evidence is valuable for evidence-based health policy-making.

The research aims of this study were first to compare and describe place of death of those persons diagnosed with lung cancer compared with those diagnosed with COPD in 14 countries and second to examine to what extent place of death differences between the two disease groups are due to confounding socio-economic and residential factors.

Results

Country and death characteristics

A total of 5,568,827 deaths were documented in the 14 countries. In all countries, except New Zealand and Mexico, more people died from lung cancer than COPD (Table 1, country abbreviations explained). Lung cancer deaths ranged from 1.2% of all in Mexico to 7.6% in the Netherlands. Deaths from COPD ranged from 1.7% in France to 5.3% in the USA.

As compared with people dying from lung cancer, those dying from COPD were more often older, female, and widowed or divorced (Table 2). Most lung cancer patients were married (England: 51.3% to Italy: 69.3%), whereas those with majority COPD were more often widowed or divorced (Spain: 37.6% to USA: 57.5%).

Place of death

From 12.5% (Korea) to 57.1% (Mexico) of persons diagnosed with lung cancer died at home (Table 3). Hospital deaths accounted for 27.5% (New Zealand) to 86.5% (Korea) of lung cancer deaths. Another 0.9% (Korea) to 22.5% (New Zealand) of lung cancer deaths occurred in nursing homes. For countries where the category hospice (i.e., palliative care institution) was available (England, Wales, New Zealand, and the USA), from 5.2% (USA) to 17.6% (New Zealand) of lung cancer deaths took place there. Of the COPD deaths, 10.4% (Canada) to 55.4% (Mexico) took place at home, 41.8% (The Netherlands) to 78.9% (Korea) in hospital, 1.5% (Korea) to 35.4% (The Netherlands) in nursing homes, and 0.2% (Wales) to 2.9% (USA) in palliative care institutions. A comparison with the place of death distribution for all-cause mortality can be found in the supplementary online appendix (Table S1).

Comparison of the place of death for COPD and lung cancer sufferers

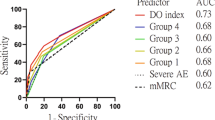

As compared with COPD sufferers, those with lung cancer had higher crude chances of dying at home in nine countries, with the difference particularly large in the Netherlands (2.34) and New Zealand (1.93) (Fig. 1). In six of these nine countries, lung cancer patients were less likely to die in hospitals. In three countries—Belgium, Italy, and Canada—persons with lung cancer had both a higher ratio of dying at home and in hospital compared with people with COPD. Those with lung cancer in all countries (except in the Czech Republic) were less likely to die in a nursing home. In countries where palliative care institutions were available as a category of place of death, lung cancer sufferers were more likely than COPD ones to die there [risk ratios: 17.93 (England), 36.82 (Wales), 9.52 (New Zealand), and 1.78 (USA)] (not presented in figure).

Crude risk ratios for dying at home, in hospital, in a nursing home, in a palliative care institution of those dying from lung cancer vs. those from COPD. Risk ratios calculated as proportion lung cancer/proportion COPD dying in each place. A risk ratio >1 indicates that those with lung cancer were relatively more likely to die in that place compared to those with COPD deaths; a risk ratio <1 means that they were less likely

Multivariable analyses

Home vs. any other place of death

Controlling for confounders (age, sex, marital status), using binary logistic regression analyses (Table 4), persons dying of COPD were significantly less likely than lung cancer patients to die at home in 10 countries [OR from 0.4 (The Netherlands) to 0.8 (Belgium, Spain, and Mexico)]. An opposite pattern was found in France (OR 1.7) and Korea (OR 1.5), with COPD sufferers there more likely to die at home.

Home vs. hospital as place of death

Lower odds ratios for home death (less than one) were observed in COPD decedents in nine countries [OR from 0.3 (The Netherlands and New Zealand) to 0.9 (Spain)] with France (OR 1.8) and Korea (OR 1.6) showing patients with COPD more likely to die in hospitals.

Hospital vs. any other place of death

Compared with those with lung cancer, COPD patients were significantly more likely to die in hospital instead of outside a hospital in seven countries [OR from 1.0 (Italy) to 2.7 (New Zealand)], but the opposite was observed in France (OR 0.5), Korea (OR 0.7), and Belgium (OR 0.8). The Czech Republic was the only country showing no differences between the two disease groups with regard to place of death.

Nursing home vs. hospital as place of death

COPD patients were more likely than lung cancer patients to die in a nursing home in five countries [OR from 1.5 (Canada) to 2.4 (Belgium)], while in five other countries (The Netherlands, The Czech Republic, England, New Zealand, USA) COPD decedents died more often in hospitals than did lung cancer decedents.

Palliative care institutions vs. any other place of death

Lastly, a comparison between palliative care institutions and other places of death for England, Wales, New Zealand, and the USA showed that in all these countries COPD decedents had a significantly lower chance of dying in a palliative care institution compared with lung cancer decedents (ORs ranging from 0.1 to 0.9).

Discussion

Main findings

This study captures variations in place of death of people dying from lung cancer and COPD, two major causes of death, across different health-care systems. We found that patients dying from COPD were more likely to die in hospital than at home (or in a palliative care institution) than those dying from lung cancer, even when considering characteristics in terms of age, gender, and marital status. France and Korea were the exceptions.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Using population death certificate data to study cross-national variation in place of death may induce some limitations that need to be taken into account.25 Due to coding and processing delays in some countries and our stipulation to select the same year across the different countries the data used are relatively old (2008) and it may be that some changes in the place of death have occurred in some countries since then.26 However, no other previous study has examined cross-national variation in place of death of people who died from lung cancer or COPD in both European and non-European countries. Death certificates have been shown to sometimes be inaccurate in recording the correct cause of death.27, 28 COPD is known to be under-reported on death certificates.29 However, for the purpose of comparison with those who died from lung cancer (which may be less prone to underreporting as a cause of death) and selection of only those people whose recorded underlying cause of death was COPD (i.e., those who died from COPD and thus were probably in an advanced stage and with a clear diagnosis of COPD at the time of death), this problem of under-reporting may be less problematic. An additional limitation, inherent to using robust population-level data, is that a loss of information at the individual level is inevitable. For instance, the death certificate does not provide information on important aspects of the end-of-life process such as preferences of place of death, choices of place of care, and course of decision-making levels, i.e., patients, family, health-care professionals, and/or health-care policy makers. Nevertheless, the statistical patterns about place of death do reflect important differences in the health-care organizational choices countries have made regarding end-of-life care in lung cancer vs. COPD and inspire further studies to provide us with a deeper understanding of observed patterns and the cross-national differences underlying those patterns.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Previous studies have found on average 75% of respondents prefer to die at home, among the terminally ill and the general public.22 However, for the majority of countries in our study, COPD decedents were substantially more likely than lung cancer decedents to die in hospital even after controlling for confounders; this may suggest a lack of options for COPD patients to die at home in most countries. This is likely to be due to a combination of factors, including a long-standing cancer focus on palliative care. COPD is an illness characterized by unpredictable exacerbations and prognosis of death. There is no clear-cut indicator with enough evidence to be effective to estimate the end-of-life phase for COPD.30 In addition, these patients and their family caregivers often do not realize that they have a limited life expectancy.8, 31 However, recently a cluster randomized controlled trial has shown that advance care planning in COPD sufferers might decrease hospitalizations and increases home deaths.32 Previous experiences have indicated that working with a coordinator for care planning may also be a way to improve end-of-life care for persons diagnosed with COPD.33 Making of advance care plans and establishing contact with end-stage care services could possibly result in a reduction of hospitalizations of advanced COPD patients at the end of life and increase the opportunity to honor their preferences for place of death.

We found that the percentages of COPD patients dying in nursing homes are substantially higher compared with lung cancer. This finding may reflect their older age and their disability or loss of functional performance in home management.34 This functional performance was found to be higher in older females,34 often leading to admission to a nursing home, and might explain why female COPD patients are more likely to die in a nursing home. However, the role of the nursing home as a place of end-of-life care and death is not well understood. Previous studies highlighted barriers to performing end-of-life care in long-term care settings because of a lack of communication and failure to initiate a palliative trajectory in good time.35, 36 This is an important consideration as hospital deaths can potentially be avoided if location preferences are known through optimal advance care planning. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in nursing homes, including policies to reduce hospitalizations at the end of life, thus seems to be an important policy priority for COPD sufferers as opposed to simply focusing all efforts on enabling them to die at home.

While the differences in terms of place of death between COPD and lung cancer decedents were large in most countries, they were very small in Italy, Spain, and Mexico. In these three countries, a relatively large proportion of both COPD and lung cancer patients died at home. This is probably due to a culture of family (or community) caregiving rather than the result of specific public health policies to facilitate home deaths. In spite of the observed general patterns of differences in place of death across the two groups of patients in each country, there were some additional cross-border differences. Home deaths were generally high for all decedents in Mexico (55.4–57.1%) and Italy (41.6–44.2%), whereas hospital deaths were high in France (60.2–77.4%) and South Korea (78.9–86.5%). The trend in France might be a result of the continued dominance of hospital-centered care and the insufficient training of oncologists and pulmonologists in palliative care. This might be understood in the light of different cultures of caregiving as well as of the surrounding medical culture. In those countries where hospice was recorded as a category, lung cancer patients were found to die there in far greater proportions than COPD patients. However, this was not the case in the USA and it might reflect how countries differ in placing the long-term focus of their palliative care services on cancer as opposed to other illnesses eligible for palliative care.7 More wider structural country-specific factors, such as insurance and reimbursement systems and regulations might, however, also play a role.

Implications for future research, policy, and practice

In order to create equal opportunities for dying at home and for access to palliative care for COPD sufferers, a “palliative care” culture for COPD is needed as well as the awareness (both in caregivers and in patients) that early discussions about end-of-life care preferences might result in better care according to the patients’ wishes and less hospitalizations and more home deaths,10 although the trajectory and the death of COPD sufferers may be more difficult to accurately predict.

Conclusions

Our study found in almost all countries that COPD sufferers as compared with lung cancer sufferers are less likely to die at home and more likely to die in a hospital or a nursing home. In the four countries that record palliative care institutions as a place of death, we found lung cancer sufferers to be much more likely to die there than COPD patients.

Materials and methods

Study design and data

This study is part of the International Place of Death (IPoD) study, which is a study of population-level death certificate data. An open call was launched by the principal investigators and candidate partners negotiated a full year’s death certificate data for inclusion. An exploration by all candidate partners revealed the most recent available year in all targeted countries was or would be 2008, which was chosen as the reference year. Exceptions were the USA (2007) and Spain (no data were recorded prior to 2010). Fourteen out of the 27 candidate countries obtained permission for data use and their data were integrated into an international database. The principal investigators pooled all data guaranteeing uniform coding throughout the database.

Death certification was executed in similar ways in the 14 countries: a physician or a qualified person such as a nurse completes the part of the death certificate indicating cause of death, time, and place of death37 along with a limited range of demographic information (e.g., sex) for the deceased. In some countries another part of the death certificate, containing more socio-demographic information about the deceased, is completed by a civil servant. All information is then processed by trained coders, following strict coding protocols, with the necessary quality checks. The death certificate data were linked across a number of countries with similar population databases such as the Census Data to include more socio-demographic information about the decedents in the database. For this study we used the death certificate data of all 14 countries included in the IPoD study: Belgium, France, Italy, Spain (Andalusia), the Netherlands, The Czech Republic, Hungary, England, Wales, New Zealand, the USA, Canada, Mexico, and Korea. More details on the database and methods can also be found in other publications based on the IPoD database.38,39,40

Data

We selected cases where lung cancer (ICD-10 codes C33-C34) or COPD (ICD-10 codes J40-44, J47) was an underlying cause of death. The outcome for our study was the place of death as recorded in the death certificate. The available categories of place of death were: hospital, home, nursing home/residential long-term care, hospice, or others. In Hungary, the death certificate only contains two categories of place of death, hospital and others, whereas hospice (e.g., palliative care institution) was only available as a category in England, Wales, New Zealand, Canada, and the USA.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine differences in the place of death between patients dying from lung cancer and those from COPD. Crude ratios (the percentages of lung cancer deaths divided by the percentages of COPD deaths) were calculated to compare the differences in place of death between the two disease groups.

Multivariable binary logistic regression models were constructed to determine the odds ratios of dying at home (comparing home vs. all other places and comparing home vs. hospital), in hospital (vs. all other places), in nursing home (vs. hospital), and in PC institutions (vs. all other places). All analyses used lung cancer as the reference group. Independent variables used in the multivariable analyses included demographics and health-care resources. Demographic factors included age (categories 0–17, 18–64, 65–85, 85 or above), sex, and marital status (unmarried, married, widowed, or divorced). Relevant confounders and covariates in the models were entered using a forward stepwise selection method with P < 0.05 set as an entry criterion.

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM-SPSS Statistics version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, 2010). For all analyses, significance was set at P < .05 (two-tailed).

References

Lozano, R. et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2095–2128 (2010).

White, P. et al. Palliative care or end-of-life care in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective community survey. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 61, e362–e370 (2011).

Gore, J. M., Brophy, C. J. & Greenstone, M. A. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax 55, 1000–1006 (2000).

Beernaert, K. et al. Referral to palliative care in COPD and other chronic diseases: a population-based study. Respir. Med. 107, 1731–1739 (2013).

Edmonds, P., Karlsen, S., Khan, S. & Addington-Hall, J. A comparison of the palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer. Palliat. Med. 15, 287–295 (2001).

Beernaert K., et al. Is there a need for early palliative care in patients with life-limiting illnesses? Interview study with patients about experienced care needs from diagnosis onward. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 33, 489–497 (2016).

Addington-Hall J., Hunt K. J. in A Public Health Perspective on End of Life Care (eds Cohen J., Deliens L.) 151–167 (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Pinnock, H. et al. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. Br. Med. J. 342, d142 (2011).

Levy, M. H. et al. Palliative care. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 10, 1284–1309 (2012).

Au, D. H., Udris, E. M., Fihn, S. D., McDonell, M. B. & Curtis, J. R. Differences in health care utilization at the end of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and patients with lung cancer. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 326–331 (2006).

Carlucci, A., Guerrieri, A. & Nava, S. Palliative care in COPD patients: is it only an end-of-life issue? Eur. Respir. Rev. 21, 347–354 (2012).

Strang, S., Ekberg-Jansson, A., Strang, P. & Larsson, L.-O. Palliative care in COPD—web survey in Sweden highlights the current situation for a vulnerable group of patients. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 118, 181–186 (2013).

Classens, M. et al. Dying with lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from SUPPORT. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 48, 146–153 (2000).

Au, D. et al. A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. Chest 14, 726–735 (2012).

Murray, S. A., Kendall, M., Boyd, K. & Sheikh, A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. Br. Med. J. 330, 1007–1011 (2005).

Lunney, J. R., Lynn, J., Foley, D. J., Lipson, S. & Guralnik, J. M. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 289, 2387–2392, doi:10.1001/jama.289.18.2387 (2003).

Seamark, D. A., Seamark, C. J. & Halpin, D. M. G. Palliative care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review for clinicians. J. R. Soc. Med. 100, 225–233 (2007).

Philip, J. et al. Palliative care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: exploring the landscape. Intern. Med. J. 42, 1053–1057 (2012).

Janssen, D. J. A. et al. A patient-centred interdisciplinary palliative care programme for end-stage chronic respiratory diseases. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 16, 189–194 (2010).

Curtis, J. R. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 32, 796–803 (2008).

Curtis, J. et al. Patients’ perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest 122, 356–362 (2002).

Gomes, B., Calanzani, N., Gysels, M., Hall, S. & Higginson, I. J. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 12, 7 (2013).

Billingham, M. J. & Billingham, S.-J. Congruence between preferred and actual place of death according to the presence of malignant or non-malignant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Supp. Palliat. Care 3, 144–154 (2013).

Teno, J. M. et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 309, 470–477 (2013).

Cohen, J. et al. Using death certificate data to study place of death in 9 European countries: opportunities and weaknesses. BMC Public Health 7, 283, doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-283 (2007).

Sleeman K., Davies J., Verne J., Gao W., Higginson I. The changing demographics of inpatient hospice death: population-based, cross-sectional study in England, 1993-2012. Lancet. 385(Suppl 1), S93 (2015).

McKelvie, P. A. Medical certification of causes of death in an Australian metropolitan hospital. Comparison with autopsy findings and a critical review. Med. J. Aust. 158, 816–818 (1993). 820–821.

Nielsen, G. P., Björnsson, J. & Jonasson, J. G. The accuracy of death certificates. Implications for health statistics. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 419, 143–146 (1991).

Drummond, M. B., Wise, R. A., John, M., Zvarich, M. T. & McGarvey, L. P. Accuracy of death certificates in COPD: analysis from the TORCH trial. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 7, 179–185 (2010).

Dijk, W. D. et al. Multidimensional prognostic indices for use in COPD patient care. A systematic review. Respir. Res. 12, 151 (2011).

Beernaert, K. et al. Early identification of palliative care needs by family physicians: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators from the perspective of family physicians, community nurses, and patients. Palliat. Med. 28, 480–490 (2014).

Thoonsen, B. et al. Training general practitioners in early identification and anticipatory palliative care planning: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 16, 126 (2015).

Epiphaniou, E. et al. Coordination of end-of-life care for patients with lung cancer and those with advanced COPD: are there transferable lessons? A longitudinal qualitative study. Prim. Care Respir. J. 23, 46–51 (2014).

Skumlien, S., Haave, E., Morland, L., Bjørtuft, O. & Ryg, M. S. Gender differences in the performance of activities of daily living among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron. Respir. Dis. 3, 141–148 (2006).

Habraken, J. M. et al. Health-related quality of life and functional status in end-stage COPD: a longitudinal study. Eur. Respir. J. 37, 280–288 (2011).

Travis, S. S. et al. Obstacles to palliation and end-of-life care in a long-term care facility. Gerontologist 42, 342–349 (2002).

Cohen, J. et al. Which patients with cancer die at home? A study of six European countries using death certificate data. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 2267–2273 (2010).

Pivodic, L. et al. Place of death in the population dying from diseases indicative of palliative care need: a cross-national population-level study in 14 countries. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 70, 17–24 (2016).

Cohen, J. et al. International study of the place of death of people with cancer: a population-level comparison of 14 countries across 4 continents using death certificate data. Br. J. Cancer 113, 1397–1404 (2015).

Reyniers, T. et al. International variation in place of death of older people who died from dementia in 14 European and non-European countries. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 165–171 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the IPoD and EURO IMPACT consortium members in giving anonymous suggestions to earlier versions of the manuscript. The International Place of Death (IPoD) study is supported by a fund from the Research Foundation Flanders. This work was supported by EURO IMPACT (FP7/2007–2013, under grant agreement no [264697]). Joachim Cohen and Lieve Van den Block are supported by a postdoctoral grant from the Research Foundation—Flanders, Belgium.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C., W.K., and K.B. did the data analyses. J.C. and W.K. started the manuscript drafting, and K.B. drafted a revised manuscript and tables after review. D.H., L.V.D.B., L.M., K.H., G.M., M.C.T., B.O.P., R.M., M.R.R., D.M.W., M.L., A.C., Y.J.R., J.T., L.D., J.C. contributed to the conceptualization of the study and data collection. D.H. and J.C. created the database and performed data cleaning. All authors read and approved the manuscript. Any further errors are solely responsible by W.K.

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, J., Beernaert, K., Van den Block, L. et al. Differences in place of death between lung cancer and COPD patients: a 14-country study using death certificate data. npj Prim Care Resp Med 27, 14 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0017-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0017-y

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating quality of care at the end of life and setting best practice performance standards: a population-based observational study using linked routinely collected administrative databases

BMC Palliative Care (2022)

-

Benefits, for patients with late stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, of being cared for in specialized palliative care compared to hospital. A nationwide register study

BMC Palliative Care (2021)

-

Changes in causes and age of death in an eastern German county over a period of 14 years. Comparison of rural and urban populations. Focus on COPD and ischemic heart disease

Journal of Public Health (2021)

-

A cluster randomized controlled trial on a multifaceted implementation strategy to promote integrated palliative care in COPD: study protocol of the COMPASSION study

BMC Palliative Care (2020)

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis of systematic fast-track transition from oncological treatment to specialised palliative care at home for patients and their caregivers: the DOMUS trial

BMC Palliative Care (2020)