Abstract

Study design:

This study was designed as an international validation study.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to assess the inter-rater reliability of the International Spinal Cord Injury Bowel Function Basic and Extended Data Sets.

Setting:

Three European spinal cord injury centers.

Methods:

In total, 73 subjects with spinal cord injury and a history of bowel dysfunction, out of which 77% were men and median age of the subjects was 49 years (range 20–81), were studied. The inter-rater reliability was estimated by having two raters complete both data sets on the same subject. First and second tests were separated by 14 days. Cohen's kappa was computed as a measure of agreement between raters.

Results:

Inter-rater reliability assessed by kappa statistics was very good (⩾0.81) in 5 items, good (0.61–0.80) in 11 items, moderate (0.41–0.60) in 20 items, fair (0.21–0.40) in 11 and poor (<0.20) in 5 items.

Conclusion:

Most items within the International Spinal Cord Injury Bowel Function Data sets have acceptable inter-rater reliability and are useful tools for data collection in international clinical practice and research. However, minor adjustments are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) has a profound impact on bowel function. Anorectal sensibility and voluntary anal sphincter contraction is reduced or lost and colorectal transit times are usually prolonged.1, 2, 3 Most individuals with SCI suffer from combinations of fecal incontinence and constipation, often with severe consequences for quality of life.4, 5, 6 Several novel treatment modalities have been introduced within the last decade. However, a Cochrane review concluded that management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) must remain empirical until well-designed controlled trials with adequate numbers and clinically relevant outcome measures become available.7 Such studies require valid instruments for the collection of data.

The International SCI Bowel Function Basic Data Set has been developed to ensure collection of clinically relevant information in a standardized form. Furthermore, the International SCI Bowel Function Extended Data Set has been developed to obtain more detailed information and facilitate comparison of results from scientific studies. Today, data sets have been developed and published for upper and lower urinary tract function, urinary tract imaging,8, 9, 10 bowel11, 12 and cardiovascular function13 and pain.14 Data sets for sexual function and quality of life have also been developed and are available at http://www.iscos.org.uk.

The International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets, developed by a working group of experts appointed by American Spinal Injury Association and International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS), were published in 2009.11, 12 The International SCI Bowel Function Basic Data Set consists of 12 items and the International SCI Bowel Function Extended Data Set of 26 items. The combined data sets contain information for computation of the Cleveland Constipation Score,15 Wexner Fecal Incontinence Score16 and NBD Score.17 Detailed guidelines have been developed to ensure a common interpretation of the data sets, but their reliability remains to be evaluated. The data sets are intended for international use and, accordingly, reliability should be tested in an international setting.

The primary aim of the present study was to test the inter-rater reliability of the International Bowel Function Basic and Extended Data Sets as recommended by the executive committee for the International SCI Standards and Data Sets.18 A secondary aim was to assess the inter-rater reliability of the Cleveland Constipation Score, the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Score and the NBD Score in subjects with SCI.

Subjects and methods

Participants

Spinal cord injury centers in Imola, Italy; Stoke Mandeville, UK and Viborg, Denmark participated in the study. Each center contributed with two raters and 24, 24 and 25 patients, respectively. The raters were doctors or nurses experienced in the treatment of SCI and NBD.

Inclusion criteria were: age older than 18 years, SCI of at least 3 months duration, sufficient mental capacity to cooperate with data collection, stable bowel function for at least 2 weeks before the first test and for the period between the two tests, that is, regular bowel pattern, unchanged use of oral laxatives and unchanged emptying routine.

Procedure

Data collection was performed from January to October 2010. The inter-rater reliability was assessed by having two raters at each center complete both data sets independently on the same patient with an interval of 14 days between the tests. This time interval was chosen as a compromise between a time period long enough to minimize the risk that the participants would remember the answers of the first test and short enough to minimize the risk of changes in bowel function. The data sets were completed by the raters during structured interviews with the patient. This was followed by digital anorectal examination.

Raters were instructed to perform approximately the same number of first and second tests. For practical purpose, no fixed order of tests was assigned. The rater of the second test was blinded to the results of the first test. In addition the International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set was completed by the rater of the first test.19

The raters consecutively included patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Immediately after completion, the data sets were mailed to the primary investigator to monitor the completeness of data collection and to ensure results from the first test were unknown to the second rater. Raters were instructed not to discuss the interpretation of items and response categories during the data collection period. The raters had no previous experience with the International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets and they did not undergo any specific training. They were, however, encouraged to consult the guidelines on the ISCoS website whenever in doubt. Interviews and examinations took place at the SCI centers.

Radiographically determined colorectal transit time is included in the International SCI Bowel Function Extended Data Set. The reproducibility and inter-rater reliability of colonic transit time in subjects with SCI has been evaluated in a previous study.20 Hence, colonic transit time was not included in the present study.

The study was performed according to the Helsinki II declaration. The participating centers obtained ethics approval according to the national regulation in their respective countries. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Translation

The original English data sets were initially translated into Italian and Danish. The translations were performed by two bilingual health professionals, experts in SCI, whose mother tongue was the target language, that is, Italian and Danish, respectively. The translations were aimed at conceptual equivalence rather than a word for word translation. The first drafts of the Italian and Danish data sets were reviewed by another independent bilingual health professional, whose mother tongue was the target language and any discrepancies were discussed until a final consensus was reached. The translation process has followed the recommendations described by Biering-Sørensen et al.18

Statistical analysis

Cohen's kappa was computed for each categorical item as a measure of agreement between first and second test.21 Ordinal data were analyzed with weighted kappa statistics.

Responses to some items in the data sets were not exclusive and it was necessary to split these into dichotomous questions for calculation of kappa statistics. Thus, the total number of questions found in the results (Tables 1 and 2) is higher than the total number of items in the data sets. The interpretation of kappa is as follows: <0.2, poor; 0.21–0.4 fair; 0.41–0.6 moderate; 0.61–0.8 good; and 0.81–1.0 very good agreement.21 An inter-rater agreement >0.20 was considered as acceptable.

Continuous data in the International SCI Bowel Function Extended Data Set were analyzed by means of the coefficient of variation (numerical difference/mean). The percentage of agreement between first and second tests was computed as a supplement to kappa statistics.

Furthermore, the coefficient of variation was calculated as a measure of the inter-rater reliability of the Cleveland Constipation Score, the NBD score and the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Score. The differences among the scores at the two tests were plotted against the average of the scores at the two tests. Limits of agreement were computed to define the limits within which 95% of the differences are expected to fall.22

The International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets lack a single question included in the NBD Score (uneasiness, headache or perspiration during defecation), and therefore the NBD score is computed solely on the remaining nine items found in the International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets. The response categories of the Cleveland Constipation Score was interpreted as described by Jorge et al.16

All statistical analyses were carried out with Stata/IC10 software (STATACORP LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

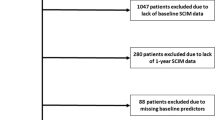

Overall, 79 first and 73 second tests were performed. Of the six patients not fulfilling the second test, three were excluded because of changes in bowel function and three did not attend their second appointment. Thus, first and second tests were obtained from 73 SCI patients; 24 at the Italian, 24 at the English and 25 at the Danish center. Approximately 77% were men, median age at injury was 44 years (range 2–75) and median age at test was 49 years (range 20–81). The three most common causes of injury were transport-related activities (41%), falls (22%) and non-traumatic causes (27%). The distribution on the American Spinal Injury Association impairment scale at acute admission was as follows: A, 60%; B, 11%; C, 16%; D, 13% (n=63).

Median time between first and second test was 14 days (range 7–36).

Only the combined results of all three centers are presented; the number of subjects from each center is not sufficient to allow reliable analysis of inter-center differences.

Kappa coefficients for each question in the International SCI Bowel Function Basic and Extended Data Sets are displayed in Tables 1 and 2.

Inter-rater reliability assessed by kappa statistics was very good (⩾0.81) in 5 items, good (0.61–0.80) in 11 items, moderate (0.41–0.60) in 20 items, fair (0.21–0.40) in 11 and poor (<0.20) in 5 items. The five questions that did not meet the lower limit of acceptable agreement were: ‘Defecation method and bowel care procedures-supplementary/mini enema’; ‘Medication affecting bowel function/constipating agents/other’; ‘Position for bowel care/other’; ‘Bowel care facilitators/other’ and ‘Lifestyle alteration due to constipation’.

In three questions, with dichotomous response, ‘yes’ was never selected in any test and, hence, no kappa coefficients could be computed. These questions were: ‘Surgical procedures on the gastrointestinal tract/ileostomy’; ‘Defecation method and bowel care procedures, supplementary/normal defecation’ and ‘sacral anterior root stimulation’.

In the basic data set, kappa could not be computed in nine dichotomous items because all agreements were placed in only one of the two diagonal boxes of the 2 × 2 table. Hence, the missing kappa value is not an expression of a low agreement, but is due to the non-computation of the kappa statistic. The percentage of agreement is displayed in the tables to supplement the kappa coefficients.

The three items with answers on a continuous scale ‘Events and intervals of defecation’ showed rather high coefficients of variation on 0.49, 0.46 and 0.56.

Cleveland Constipation Score, NBD Score and Wexner Fecal Incontinence Score were computed from data within the International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets. The inter-rater reliability of these scores is displayed by means of Bland–Altman plots with limits of agreement in Figures 1,2,3. The coefficients of variation of these three scores is displayed in Table 3.

Discussion

The International Spinal Cord Injury Data Sets have been developed to ensure a common international collection of relevant data on various aspects of SCI.20 When introducing a new instrument for measuring health, a comprehensive validation should be performed. The first step is usually to test reliability to determine whether the instrument is collecting data in a reproducible manner. Variations within the subject, within the rater, between raters or between different settings should be considered. Furthermore, the content validity should be explored to ensure that the selected items are relevant and able to describe the underlying concept in an exhaustive manner.22 The content validity of the International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets was established through the process of development, in which experts appointed by ISCoS and American Spinal Injury Association, on the basis of a literature search, discussed and reached consensus on which items should be included.11, 12 Relevant and interested scientific and professional international organizations and societies were invited to review the data sets and they were posted on the ISCoS and American Spinal Injury Association websites for 3 months to allow comments and suggestions.

The aim of the present study was to determine the inter-rater reliability of the International Spinal Cord Injury Bowel Function Basic and Extended Data Sets.11, 12 Inter-rater reliability was acceptable (kappa >0.2) in 47 of 52 items, in which kappa coefficients could be computed. We recommend that the five items showing ‘poor agreement’ (kappa <0.2) are revised and subsequently retested. If acceptable reliability is unobtainable in these items, their exclusion from the data sets should be considered.

Variation between first and second test is not due only to differences between raters. Intra-rater variation and variation within each patient also contribute. The intra-rater reliability of the data sets was not tested because an acceptable inter-rater reliability indicates that the intra-rater reliability is also acceptable.18, 23 Establishing high inter-rater reliability is the priority as the data sets will be used by many different raters in the future. We chose to separate the first and second test by a period of 2 weeks and it is possible that bowel function may have changed slightly in this period of time; this would affect the intra-subject variation. As we minimized this risk by excluding patients who had objective changes in bowel function and management during the period between tests, we consider this risk small.

We chose a kappa >0.20 as the minimum limit of acceptable agreement. Whether this limit should be higher is open for discussion. In general, a lower reliability must be expected when studying self-reported and partly subjective outcomes, as opposed to strictly objective outcomes. Furthermore, the data sets are not intended for making decisions on potentially high-risk treatment in which case a high reliability (kappa>0.8) is usually required.

Combining the basic and extended data set allows computation of the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Score,16 the Cleveland Constipation Scoring System17 and the NBD Score.18 The present study is the first to evaluate the inter-rater reliability of these scores in a population with SCI. Variation, expressed in terms of coefficient of variation, was surprisingly high, especially for the Wexner fecal incontinence score. We find that these existing scores for bowel function should be further evaluated in individuals with SCI.

The International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets allow a straightforward computation of the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Score. The wordings of some items in the two other scores are not completely equivalent with those of the items in the International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets, and a single item is missing to allow a complete computation of the NBD Score. Revision of the International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets is recommended to allow straightforward computation of all three bowel function scores.

In some data set items, the most extreme responses were rarely or never selected, and hence this evaluation of the data sets is limited to the responses used by the patients included. Our study population was too small to decide whether these response categories will be used in future studies and clinical practice. However, some of them are necessary as part of the abovementioned scores. Also, some of the items with dichotomous answers only used one. Unless the data sets perform differently in a larger population, exclusion of these items should be considered when revising them.

There were several common practical problems. For instance it was not explicitly stated on the data collection form whether response categories were exclusive or not. In a number of cases, when only one response was allowed, raters selected several response categories. In another example, the item ‘medication affecting bowel function/constipating agents’ in the basic data set caused confusion, because raters initially included laxatives. Confronted with the next item ‘oral laxatives’, it became clear to raters what the former item was asking. By reversing the order of the two items this problem could be avoided.

In addition, we recommend adding a response category ‘stoma’ to the question ‘position for bowel care’ in the extended data set, as the raters obviously needed this option. The guidelines posted on the ISCoS website were rarely used by the raters (3–4 times per rater); development of self-explanatory data sets that could easily be completed without the need for separate guidelines should be considered. Alternatively, development of patient-completed questionnaires, including the main part of the bowel function items, as produced by Jensen et al.24 for the pain data set, might improve the usefulness of the data sets and save precious time in clinical practice.

On the basis of our experiences in the present study, we recommend that the remaining SCI data sets are subjected to similar evaluation.

Conclusion

The International SCI Bowel Function Data Sets have shown an inter-rater agreement that was very good in 5 items, good in 11 items, moderate in 20 items, fair in 11 items and poor in 5 items. The data sets provide a reliable and useful tool in spinal cord injury research and clinical practice. Nevertheless the five items with poor agreement need to be revised.

References

Krogh K, Mosdal C, Laurberg S . Gastrointestinal and segmental colonic transit times in patients with acute and chronic spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 615–621.

Menardo G, Bausano G, Corazziari E, Fazio A, Marangi A, Genta V et al. Large-bowel transit in paraplegic patients. Dis Colon Rectum 1987; 30: 924–928.

Keshavarzian A, Barnes WE, Bruninga K, Nemchausky B, Mermall H, Bushnell D . Delayed colonic transit in spinal cord-injured patients measured by indium-111 Amberlite scintigraphy. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90: 1295–1300.

Glickman S, Kamm MA . Bowel dysfunction in spinal-cord-injury patients. Lancet 1996; 347: 1651–1653.

Lynch AC, Wong C, Anthony A, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA . Bowel dysfunction following spinal cord injury: a description of bowel function in a spinal cord-injured population and comparison with age and gender matched controls. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 717–723.

Faaborg PM, Christensen P, Finnerup N, Laurberg S, Krogh K . The pattern of colorectal dysfunction changes with time since spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 234–238.

Coggrave M, Wiesel PH, Norton C . Management of faecal incontinence and constipation in adults with central neurological diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (2): CD002115.

Biering-Sorensen F, Craggs M, Kennelly M, Schick E, Wyndaele JJ . International urodynamic basic spinal cord injury data set. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 513–516.

Biering-Sorensen F, Craggs M, Kennelly M, Schick E, Wyndaele JJ . International lower urinary tract function basic spinal cord injury data set. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 325–330.

Biering-Sorensen F, Craggs M, Kennelly M, Schick E, Wyndaele JJ . International urinary tract imaging basic spinal cord injury data set. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 379–383.

Krogh K, Perkash I, Stiens SA, Biering-Sorensen F . International bowel function basic spinal cord injury data set. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 230–234.

Krogh K, Perkash I, Stiens SA, Biering-Sorensen F . International bowel function extended spinal cord injury data set. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 235–241.

Krassioukov A, Alexander MS, Karlsson AK, Donovan W, Mathias CJ, Biering-Sorensen F . International spinal cord injury cardiovascular function basic data set. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 586–590.

Widerstrom-Noga E, Biering-Sorensen F, Bryce T, Cardenas DD, Finnerup NB, Jensen MP et al. The international spinal cord injury pain basic data set. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 818–823.

Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, Reissman P, Wexner SD . A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 681–685.

Jorge JM, Wexner SD . Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 77–97.

Krogh K, Christensen P, Sabroe S, Laurberg S . Neurogenic bowel dysfunction score. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 625–631.

Biering-Sorensen F, Alexander MS, Burns S, Charlifue S, Devivo M, Dietz V et al. Recommendations for translation and reliability testing of international spinal cord injury data sets. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 357–360.

DeVivo M, Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, Noonan V, Post M, Stripling T . et al. International spinal cord injury core data set. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 535–540.

Media S, Christensen P, Lauge I, Al-Hashimi M, Laurberg S, Krogh K . Reproducibility and validity of radiographically determined gastrointestinal and segmental colonic transit times in spinal cord-injured patients. Spinal Cord 2008; 47: 72–75.

Altman D . Practical Statistics For Medical Research. Chapman and Hall: London, 1991, p 404–409.

Bland JM, Altman DG . Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 1: 307–310.

Streiner D, Norman G . Health Measurement Scales. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2008, p 182.

Jensen MP, Widerstrom-Noga E, Richards JS, Finnerup NB, Biering-Sorensen F, Cardenas DD . Reliability and validity of the International Spinal Cord Injury Basic Pain Data Set items as self-report measures. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 230–238.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Juul, T., Bazzocchi, G., Coggrave, M. et al. Reliability of the International Spinal Cord Injury Bowel Function Basic and Extended Data Sets. Spinal Cord 49, 886–891 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.23

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.23

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Are micro enemas administered with a squeeze tube and a 5 cm-long nozzle as good or better than micro enemas administered with a 10 cm-long catheter attached to a syringe in people with a recent spinal cord injury? A non-inferiority, crossover randomised controlled trial

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Study protocol of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial on the effect of a multispecies probiotic on the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in persons with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Development of a novel neurogenic bowel patient reported outcome measure: the Spinal Cord Injury Patient Reported Outcome Measure of Bowel Function & Evacuation (SCI-PROBE)

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Reliability of the International Spinal Cord Injury Upper Extremity Basic Data Set

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

Neurogenic bowel management for the adult spinal cord injury patient

World Journal of Urology (2018)