Abstract

The heterotrimeric Sec61 complex and the dimeric Sec62/Sec63 complex are located in the membrane of the human endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and play a central role in translocation of nascent and newly synthesized precursor polypeptides into the ER. This process involves targeting of the precursors to the membrane and opening of the polypeptide conducting Sec61 channel for translocation. Apart from this central role in the intracellular transport of polypeptides, several studies of the last decade uncovered additional functions of Sec proteins in intracellular signaling: Sec62 can induce ER-phagy in the process of recovery of cells from ER stress and the Sec61 channel can also act as a passive ER calcium leak channel. Furthermore, mutations, amplifications and an overexpression of the SEC genes were linked to various diseases including kidney and liver diseases, diabetes and human cancer. Studies of the last decade could not only elucidate the functional role of Sec proteins in the pathogenesis of these diseases, but also demonstrate a relevance of Sec62 as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in head and neck cancer, prostate and lung cancer including a basis for new therapeutic strategies. In this article, we review the current understanding of protein transport across the ER membrane as central function of Sec proteins and further focus on recent studies that gave first insights into the functional role and therapeutic relevance of Sec61, Sec62 and Sec63 in human diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Protein transport into and across the ER membrane

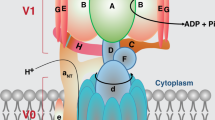

The transport of precursor proteins into and across the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane represents a highly conserved process in eukaryotic cells and is essential for the biogenesis of many transmembrane and most secretory proteins.1–3 Basically, this process can be divided into three major steps as follows: (i) the targeting of nascent and newly synthesized precursor polypeptides to the ER membrane; (ii) the insertion of the protein into the polypeptide conducting channel; and (iii) the lateral release of the transmembrane protein from the channel into the phospholipid bilayer or the completion of translocation into the ER lumen. As there are some mechanistic differences depending on the precursor protein being translocated during or after its synthesis at the ribosome, one can distinguish between the cotranslational4,5 (Figure 1a) and the posttranslational transport mechanism6,7 (Figure 1b). During co-translational transport, the ribonucleo-complex signal recognition particle (SRP)8 binds to a hydrophobic signal sequence located at or near the N terminus of the nascent precursor polypeptide and to the ribosome.9 Subsequently, the SRP receptor guides the ribosome nascent chain complex to the polypeptide conducting channel Sec61.10 Following GTP hydrolysis, SRP dissociates from the ribosome and the SRP receptor11–13 inducing a resumption of protein synthesis and the nascent polypeptide chain inserts into the Sec61 channel. Subsequently, membrane proteins diffuse laterally from the Sec61 complex into the bilayer. Alternatively, ER luminal chaperone proteins such as BiP/Grp78 can function as ‘molecular ratchets’ and guarantee the unidirectional transport of the nascent protein through the Sec61 channel into the ER lumen.14–16 To facilitate an interaction between these chaperones and the precursor polypeptides in transit, J domains of ER transmembrane proteins such as Sec63 mediate their direct interaction.17–23 As the activity of ER luminal BiP depends on ATP hydrolysis, the nucleotide-exchange factors Sil1 and GRP170 guarantee a replacement of ADP with ATP.24 During or after the precursor protein translocation is completed, the signal sequence is cleaved off by the signal peptidase complex,25 which is followed by folding of the translocated protein and covalent modifications such as N-glycosylation.26

Protein transport across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Mechanism of (a) co-translational and (b) posttranslational transport of precursor proteins through the Sec61 channel. (c) Topological domains of Sec61α1/ß/γ, (d) Sec62 and (e) Sec63. We note that (i) Sec63 interacts with Sec62 involving a cluster of negatively charged amino-acid residues near the C terminus of Sec63 and positively charged cluster in the N-terminal domain of Sec62,43 (ii) Sec62 interacts with the N-terminal domain of Sec61α via its C-terminal domain,68 (iii) BiP can bind to ER luminal loop 7 of Sec61 α via its substrate-binding domain and mediated by the ATPase domain of BiP and the J-domain in the ER luminal loop of Sec63,53 (iv) Ca2+-CaM can bind to an IQ motif in the N-terminal domain of Sec61α64 and (v) LC3 can bind to a LIR motif in the C-terminal domain of Sec62.71 40S, 40S ribosome subunit; 60S, 60S ribosome subunit; SR, heterodimeric SRP receptor; SRP, signal recognition particle.

The posttranslational transport is characterized by some crucial differences compared with the above-described co-translational transport mechanism: The precursor proteins are fully synthesized at free ribosomes because they bear a signal sequence of relatively low hydrophobicity (in yeast), or are simply too short (in mammals) to efficiently and productively interact with SRP at the ribosome, which leads to a completion of translation in the cytosol.27,28 To maintain a protein structure compatible with translocation across the ER membrane, cytosolic Hsp40 and Hsp70 chaperones prevent extensive protein folding at this stage and keep the signal sequence free for interaction with receptors at the ER surface.29–31 Depending on structural characteristics of the synthesized protein, for example, the chain length and the extent of folding, SRP as well as Sec62 can be required for an efficient targeting to the Sec61 translocon.23,32–34 The subsequent steps of protein transport are comparable with the co-translational transport. Figures 1a and b give an overview of the co- and posttranslational mechanism of protein transport into and across the ER membrane.

For both the co- and posttranslational transport, the protein translocation machinery as core element is composed of the ER transmembrane proteins Sec61, Sec62 and Sec63 (ref. 35) with Sec61 being composed of the three subunits Sec61α, Sec61ß and Sec61γ.36–41 These Sec proteins form oligomers with direct interactions of Sec62 and Sec63 to each other as well as to the Sec61 channel.42,43 However, only Sec61 and Sec62 but not Sec63 can directly interact with the ribosome.43 The topological domains of Sec61, Sec62 and Sec63 are shown in Figures 1c–e.

Sec61 as central element of the protein translocation machinery forms a protein conducting channel with an aqueous central pore.44 Precursor polypeptides can either completely cross the ER membrane through the Sec61 channel or exit laterally into the lipid phase of the membrane if the protein contains hydrophobic transmembrane domains.45 This evolutionarily conserved heterotrimeric mammalian ortholog to the bacterial protein SecY was characterized in detail in its structure and function over the past years.10,36–41,46

After its first functional and topological description in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the late 1980s,47–49 a homolog to yeast Sec62p in mammals was identified in 1997.35,42,50 In mammalian cells, Sec62 interacts with Sec61 as well as Sec63 and, contrary to its yeast ortholog, harbors two conserved peptide domains at its cytosolic N terminus allowing a binding to the ribosome.43 The detailed function of Sec62 in the protein translocation process still remains uncertain though several studies of the past decade indicated a role of Sec62 in posttranslational transport: Lakkaraju et al. found that posttranslationally transported precursor proteins comprising ⩽100 amino acids strongly and precursor proteins comprising 120–160 amino acids partially depend on Sec62 for efficient translocation.33 In a study by Lang et al., SEC62 silencing led to a reduced ability for posttranslational import of small presecretory proteins without any impairment of co-translational transport or posttranslational membrane insertion of tail-anchored proteins.23 These findings are consistent with comparable observations in yeast,51,52 where Sec62p together with Sec61p, Sec63p, Sec71p and Sec72p forms the so-called ‘posttranslational translocon’. Against this background, the question about the functional relevance of the ribosome-binding site of Sec62 remains unanswered. Eventually, further studies are needed to elucidate the detailed function of Sec62 in the protein translocation process.

The Sec63 protein consists of three transmembrane domains with the ER luminal loop harboring a J-domain that allows an interaction with chaperones—such as BiP—to facilitate the unidirectional translocation of precursor proteins through the Sec61 translocation pore. Moreover, Lang et al. reported a precursor-specific role of Sec63, in cooperation with BiP, in the early phase of co-translational protein transport with proteins as pERj3, PrP and ppcecA being dependent on Sec63 for efficient initial insertion into the Sec61 channel.23,53 However, Görlich and Rapoport showed that neither Sec63 nor BiP is required for an efficient translocation of several other precursor proteins as preprolactin and VSV G protein in an in vitro protein transport model.10 Hence, the mechanism of how Sec63 acts in transport as well as its substrate specificity remains elusive. The testing of further potential substrates will be required to clarify which subset of proteins is dependent on Sec63 for efficient transport.

In addition to Sec-dependent transport of precursors with N-terminal signal peptides or internal transmembrane helices serving as signal sequences, there is a posttranslational mechanism for tail-anchored membrane proteins with C-terminal tail anchors.3 This mechanism involves cytosolic and membrane proteins for targeting and membrane integration, the so-called transmembrane recognition complex (reviewed in Borgese and Fasana3).

Role of sec proteins in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis and autophagy

An additional function for Sec61 apart from protein translocation was suggested by several studies, indicating that Sec61 could also serve as a Ca2+ channel that allows a passive efflux of Ca2+ ions from the ER lumen—the largest intracellular Ca2+ store—to the cytosol.37,54–61 Thus, Sec61 counteracts the active import of Ca2+ into the ER lumen through the sarcoplasmic/ER Ca2+ ATPase.62 In fact, Lang et al.63 were the first who could directly measure this Ca2+ flow through the open Sec61 channel in planar lipid bilayer experiments and link it to the Sec61 complex at the cellular level by siRNA-mediated knockdown experiments in combination with live-cell calcium imaging.64 As the cytosolic Ca2+ level crucially influences essential cellular processes as cell migration65 and apoptosis66—processes that both are seriously disturbed by an uncontrolled Ca2+ efflux from the ER67—it was suggested that the passive Ca2+ efflux through the Sec61 channel is regulated by diversified mechanisms: as first mode of regulation, Erdmann et al.64 could show that cytosolic calmodulin (CaM) can efficiently bind to the cytosolic site of Sec61 in a Ca2+-dependent manner, thus limiting Ca2+ efflux from the ER lumen. In addition, the chaperone BiP was shown to decrease the Sec61-mediated Ca2+ efflux too, by binding to the loop 7 of Sec61α from the ER luminal site.53 As a third regulatory mechanism, Linxweiler et al.68 showed that SEC62 silencing increases the Ca2+ efflux from the ER, suggesting that the Sec62 protein also contributes to limit the Sec61-mediated Ca2+ flow (Figure 2a). As a point mutation (D308A) in a putative C-terminal EF hand domain of Sec62 failed to rescue the effect of Sec62 depletion on Ca2+ efflux contrary to a transfection of the cells with a wild-type plasmid,68 this regulatory effect is probably mediated by the C-terminal EF hand motif of Sec62. According to our working model, Ca2+ efflux leads to Ca2+ binding to the EF hands of Sec62 and CaM, conformational changes in these two proteins, and subsequent dissociation of Ca2+-Sec62 from the N terminus of Sec61α and simultaneous binding of Ca2+-CaM to an IQ motif in this N-terminal domain. Apart from that, Crowley et al.69 hypothesized based on transport experiments with fluorescently labeled translocation substrates and ER luminal iodide ions for collisional quenching that the Sec61 channel is impermeable to ions during the translocation of a nascent chain with the ribosome bound to Sec61. To what extent the Sec61-mediated Ca2+ efflux from the ER lumen and its regulatory mechanisms contribute to the global cellular Ca2+ homeostasis and how this is orchestrated with the other mechanisms of intracellular calcium signaling70 are important questions that have to be addressed by future studies.

Regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis at the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and Sec62-mediated autophagy. (a) Regulation of Ca2+ efflux through the Sec61 channel. (b) Sec62-mediated autophagy. The red arrows in a indicate inhibitory effects on the passive Ca2+ efflux through the Sec61 channel. 40S, 40S ribosome subunit; 60S, 60S ribosome subunit; CaM, calmodulin; CALR, calreticulin; LC3, 1A/1B-light chain 3; SERCA, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase.

An additional function beyond protein translocation and calcium homeostasis was recently found for the Sec62 protein as well. Fumagalli et al.71 showed that Sec62 plays a crucial role in the recovery of eukaryotic cells from conditions of ER stress. The term ER stress describes conditions under which the homeostasis of protein synthesis, folding and transport at the ER is disturbed due to the perturbation of ER environment.70 Depending on the severity of stress, the cell can either initiate compensatory mechanisms that are entirely referred to as unfolded protein response or undergo programmed cell death,70 which involves—possibly Sec61 channel mediated—Ca2+ efflux from the ER. During unfolded protein response, ribosomal synthesis of the majority of proteins is blocked, the expression level of several ER luminal chaperones, such as BiP and Herp, is markedly increased to facilitate a correct folding of ER luminal polypeptides and, in the case of defective repair, misfolded proteins are degraded via a mechanism called the ER-associated protein degradation.72,73 If the cell can finally cope with ER stress conditions, the expanded ER itself as well as the high amount of ER luminal chaperones have to be downsized to a physiological level again. Therefore, small vesicles bearing ER luminal and membrane chaperones are separated from the ER membrane, fuse with phagophores to build autophagosomes and finally are delivered to lysosomes for degradation—a process called autophagy (Figure 2b).74 In this context, Sec62 was shown to bear a LIR motif at its C terminus functioning as a receptor for phagophore-bound LC3 on recovery from ER stress induced by cyclopiazonic acid or dithiothreitol.71 The interaction between the LIR motifs and LC3 induces the formation of autophagosomes and their delivery to lysosomes.74 Thus, Sec62 plays an important, Sec61- and Sec63-independent, role during the compensation of ER stress—a process the authors described as recovER-phagy.71

Taken together, it was shown that Sec61 and Sec62 bear important functions beyond the protein translocation process, indicating that Sec proteins can influence intracellular signaling in various manners. How these additional functions are controlled in detail and how they are linked to other cellular signaling pathways remain elusive.

Mutation and overexpression of Sec genes in human diseases

Over the past years, mutations, amplification and overexpression of SEC61, SEC62 and SEC63 have been linked to numerous human diseases (Figure 3). In 2004, Sec63 was the first human Sec protein being linked to a human disease, as Davila et al.75 showed that autosomal-dominant polycystic liver disease can be caused either by mutations in the SEC63 gene or mutations in the protein kinase C substrate 80K-H gene (PRKCSH). For SEC63, two frameshift mutations, two nonsense mutations and two mutations predicted to disrupt splice donor–acceptor sites were described in a collective of 63 individuals, all leading to a loss of gene function. Further studies confirmed these results and strengthened the role of SEC63 as a driver gene in the pathogenesis of autosomal-dominant polycystic liver disease by the disruption of co-translational transport of proteins, such as polycystins I and II, into the ER.76–79

Comparably, loss-of-function mutations have also been described for the SEC61A1 gene and could be linked to autosomal-dominant tubulo-interstitial kidney disease in humans (ADTKD)80 as well as diabetes and hepatosteatosis in mice.81 Bolar et al. investigated renal tissue samples from two families with ADTKD and identified two different missense variants of SEC61A1 (c.553A<G (p.Thr185Ala) and c.200T<G (p.Val67Gly)), whereas none of the otherwise frequently mutated genes UMOD, MUC1 and REN were altered. The defective Sec61α1 variants were delocalized to the Golgi apparatus and, when induced in zebrafish embryos, led to convolution defects of the pronephric tubules consistent with the histological findings in ADTKD patients.

Another mutation of the SEC61A1 gene (Y344H) was found to cause excessive ER stress and, as a consequence, inducing apoptosis of pancreatic ß-cells in C57BL/6 mice, which finally led to diabetes and hepatosteatosis. Thereby, transgenic ß-cell-specific expression of normal SEC61A1 could rescue diabetes and ß-cell loss in mutant mice proving a critical role of Sec61α1 in the ß-cell response to glucose. One study introduced the mutant SEC61A1 variant together with SEC61A1 targeting siRNA into human cells and observed that the mutant Sec61 channel could not substitute for the wild-type channel with respect to BiP-dependent protein transport into the ER and cellular calcium homeostasis.53 Therefore, this study suggested that the mutated SEC61A1 gene causes apoptosis of professional secretory cells such as ß-cells because of disturbed calcium homeostasis. However, no study has investigated so far the impact of this point mutation in human patients suffering from diabetes so that a direct link to human disease is still missing.

Apart from the mentioned kidney, liver and metabolic diseases, mutations and especially an amplification and overexpression of SEC genes were found to be frequent molecular characteristics of various human tumor diseases (Table 1). For SEC63, frameshift mutations caused by microsatellite instability were found in 37.5% of microsatellite-unstable gastric cancers,82 48.8% of colorectal cancers,82 56% of small-bowel cancer associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer83 and in one case of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with Lynch syndrome.84 However, functional analyses to further uncover the role of Sec63 in human carcinogenesis were solely conducted by Casper et al.,84 who showed that a low hepatic expression of SEC63 correlated with a decreased apoptosis rate and an increased proliferative activity of hepatocytes in BXD mice. Altogether, these studies indicate a potential role of SEC63 as a tumor suppressor gene in the carcinogenesis of gastric cancer, colorectal cancer and hepatocellular cancer (HCC) without, however, providing a link of disrupted Sec63 function to tumor cell biology in these entities.

For SEC61, only one study reported a potential relevance in human cancer so far.85 In this study, copy-number changes and the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of the Sec61γ-coding gene (SEC61G) were investigated in 43 human glioblastoma samples using quantitative PCR. Thereby, high copy-number gains (>4-fold) were found in 47% and an overexpression compared with healthy brain tissue in 77% of cases. Neither the genes coding for Sec61α (SEC61A1) nor for Sec61ß (SEC61B) showed comparably high expression levels with, however, a tendency to an elevated expression of both genes in glioblastoma samples compared with healthy brain tissue. When silencing the SEC61G gene in the human glioblastoma cell line H80, Lu et al. could observe reduced cell viability with an increased rate of apoptosis. Induction of ER stress by treating H80 and HeLa cells with tunicamycin—an inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation—led to an increase in SEC61G expression, indicating a potential role of Sec61γ in ER stress response. As several other studies reported a general ER expansion under conditions of ER stress,86,87 it is uncertain if Sec61γ has further functions during the compensation of ER stress apart from expanding ER capacity.

The strongest evidence for a causative role in cancer development and tumor cell biology exists for SEC62 with the first association with human cancer having been reported in 2006: Jung et al.88 investigated copy-number changes in 22 prostate cancer samples and found copy-number gains of the SEC62 gene in 50% of cases as well as increased SEC62-mRNA levels in all analyzed samples. Following the promising results of this study, Greiner et al.89 investigated SEC62 expression at the protein level in 2071 tissue samples from 55 different tumor entities in an immunohistochemical multitissue tumor microarray. Thereby, 72% of all tumors showed detectable expression levels of SEC62 with the highest percentage of an increased expression compared with healthy tissue from the same origin in lung cancer (93–97%, depending on the subtype) and thyroid cancer (87–100%, depending on the subtype). These results for lung and thyroid cancer were confirmed in a study by Linxweiler et al.,90 including 70 non-small-cell lung cancer cases and 10 thyroid cancer cases. Increased Sec62 protein and SEC62-mRNA levels compared with healthy lung tissue from the same patients were detected in 80% and 60.9% of cases, respectively. For thyroid cancer, increased Sec62 protein levels were observed in 40% and increased SEC62-mRNA levels in 60% of cases. A study focusing on SEC62 expression in dysplastic cervical lesions91 found SEC62 amplifications in 23% and increased Sec62 protein levels in 100% of cervical cancer cases with a gradually increasing SEC62 expression depending on the severity of dysplasia. Wemmert et al.92 investigated the expression of SEC62 in 35 cases of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas using immunohistochemistry and found a strong staining intensity in 34% and a moderate staining intensity in 23% of cases. Another study focused on the expression of SEC62 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 80 HCC patients and 30 healthy individuals. Hereby, Sec62-mRNA and protein content were significantly higher in the blood samples from HCC patients compared with healthy controls.93

On the whole, all studies addressing the expression of SEC62 in human cancer so far consistently reported an increased SEC62 expression level for the majority of investigated cases both in the tumor tissue88–92,94 and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells,93 suggesting that SEC62 plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of various tumor entities and bears a potential oncogenic function. This hypothesis is further substantiated by the fact that the SEC62-encoding chromosomal region 3q26 is amplified in numerous human cancer entities including cervical cancer,95,96 non-small-cell lung cancer,97 esophageal cancer,98 ovarian cancer,99 and head and neck cancer.100,101 Hagerstrand et al.102 screened 3131 tumor samples from 26 different tumor entities for somatic copy-number alterations and found the SEC62-encoding region 3q26 to be amplified in 22% of cases. Indeed, a following systematic interrogation of 3q26 by gain- and loss-of-function studies identified SEC62/TLOC1 as a ‘tumor-driver gene’ encoded in this region. The same group investigated the effect of short hairpin RNA-mediated SEC62 knockout on the proliferation of 16 different human cell lines and found that cell lines harboring an 3q26 amplification rely on SEC62 for normal proliferative activity. Moreover, SEC62 overexpression increased anchorage-independent growth in human mammary epithelial cells and induced subcutaneous tumor growth of otherwise non-tumor-forming murine embryo fibroblasts (NIH3T3) in C.Cg/AnNTac-Foxn1nunu mice102 again pointing to a potential oncogenic function of SEC62.

To identify further roles of Sec62 in tumor cell biology apart from the known function in protein translocation across the ER membrane, several studies investigated the effect of SEC62 silencing and SEC62 overexpression on neoplastic and non-neoplastic human cell lines. Consistently, a SEC62 knockdown markedly reduced the migration and invasion potential of prostate cancer cells90 as well as the migration of NSCLC cells,90 thyroid cancer cells90 and cervical cancer cells,91 whereas SEC62 overexpression stimulated the migration of cervical cancer cells91 and even human embryonic kidney cells.90 The latter is particularly telling since it provided a direct link between Sec62 and cell migration. Of note, neither SEC62 silencing nor SEC62 overexpression markedly affected cell proliferation in these studies.89–91 However, other studies reported an impairment of cell proliferation in Sec62-depleted cell lines harboring a 3q26 amplification102 as well as in Sec62-depleted HeLa cells.32 Though all of these studies indicate a crucial role of SEC62 in cancer cell migration and invasion—molecular processes that are essential for tumor metastasis—it is not yet clear how this function of Sec62 is mediated on the molecular level. As Sec62 is involved in the protein translocation process at the ER, it is conceivable that a distinct subset of migration-relevant precursor proteins rely on Sec62 for efficient transport. However, no according substrates have been identified so far. Linxweiler et al.91 investigated a potential role of SEC62 in the induction of epithelial–mesenchymal transition, a highly conserved molecular process that is essential for metastasis formation, but found no influence of Sec62 on the expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition markers as vimentin and E-cadherin. Apart from that, the inhibitory effect of high SEC62 expression levels on the Sec61-mediated Ca2+ efflux from the ER lumen68 represents a possible connection between Sec62 and cell migration. Though the exact molecular mechanisms linking Sec62 and the Ca2+ efflux as well as Ca2+ and cellular migration remain elusive.

In addition to an increased potential for migration and invasion, SEC62 overexpressing cancer cells were found to exhibit a higher tolerance to cellular stress, such as thapsigargin (TG)-induced ER stress,89,90 another hallmark of cancer cells. Again, increased calcium stress tolerance could be induced by SEC62 overexpression in human embryonic kidney cells90 and was reduced by SEC62 knockdown from cancer cells, thereby providing a direct link between SEC62 overexpression and tolerance to cellular calcium stress (see below).

Taken together, functional analyses investigating the role of Sec62 in tumor cell biology have shown that tumor cells could profit from an increased SEC62 expression level in terms of an increased capability to migrate and invade the surrounding tissue, which is essential for the formation of metastases. In addition, the recently observed function of Sec62 in the recovery from ER stress71 represents a further potentially beneficial effect of high SEC62 expression levels for tumor cells and maybe linked to the role of Sec62 in stress tolerance.

Sec proteins as molecular biomarkers and therapeutic targets in human cancer

To explore the clinical relevance of Sec62 as a potential biomarker especially in tumor diseases, the SEC62 expression level of the respective tumor tissue as well as peripheral blood mononuclear cells was correlated with the patients’ clinical data, including TNM stage and survival in several of the before-mentioned studies. Hereby, Greiner et al.94 found a correlation between the Sec62 protein levels in prostate cancer tissue with the patients’ Gleason score—a histopathological grading system with high scores indicating a poor prognosis—indicating a worse outcome for patients with higher Sec62 levels. Comparably, the Sec62 protein levels in NSCLC as well as head and neck squamous cell carcinomas tissue samples significantly correlated with a shorter overall survival.68,92 For NSCLC patients, an additional correlation of high Sec62 levels with a dedifferentiation of the tumors and the occurrence of lymph node metastases was found,90 again pointing to a potential function of Sec62 in tumor metastasis. In HCC patients, a high expression of SEC62 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlated with a reduced recurrence-free survival characterizing Sec62 as an independent predictor of HCC recurrence.93 In contrast, prostate cancer patients with SEC62 copy-number gains showed a lower risk of and a longer time to progression compared with patients without SEC62 copy-number gains in the study by Jung et al.88 Considering the comparably low number of patients in this study (n=22) and the consistent findings of the other studies, Sec62 seems to be an independent biomarker for the patients’ prognosis in several human cancers. To confirm this potential role of Sec62 as a prognostic marker and to establish a valid basis for clinical applications, further tumor entities enclosing larger patient cohorts have to be investigated in future studies.

Though Sec61 and Sec63 have been linked to human diseases as well, a potential function of these proteins as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers seems unlikely, as all diseases showing SEC61A1 and SEC63 mutations can also be caused by other genetic alterations.80,81,103 In the context of human cancer, the percentage of gastric cancer,82 small-bowel cancer83 and colorectal cancer cases82 showing frameshift mutations of SEC63 as well as the percentage of glioblastoma cases showing a SEC61G amplification and overexpression85 is too low to allow diagnostic conclusions. A potential correlation of SEC63 and SEC61G expression levels with the patients’ survival has not been investigated so far.

Regarding the relevance of Sec62 as a prognostic biomarker in different cancer entities and the stimulation of tumor cell migration and invasion by high SEC62 expression levels in cell culture experiments, one can hypothesize that a suppression of SEC62 gene function could possibly influence tumor metastasis in vivo too. Unfortunately, there are many known synthetic (eeyarestatin I and cotransin) and natural inhibitors (exotoxin A, mycolactone and apratoxin A) of the Sec61 channel (Figure 4),104–109 but no direct inhibitors of Sec62 and Sec63. However, it is possible to antagonize the function of Sec62 in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis by either inhibiting the sarcoplasmic/ER Ca2+ ATPase and thereby decreasing the active Ca2+ import from the cytosol into the ER lumen, or antagonizing the CaM-mediated Sec61 closure with CaM antagonists and thereby increasing the passive Ca2+ efflux from the ER lumen through the Sec61 channel (Figure 4). Linxweiler et al.68 performed in vitro experiments to investigate a possible phenocopy of SEC62 gene silencing in human tumor cells by the treatment with CaM antagonists. Indeed, the CaM antagonists trifluoperazine (TFP) and ophiobolin A induced a dose-dependent inhibition of tumor cell migration, an additional inhibition of tumor cell proliferation at higher concentrations and sensitized the cells to TG)-induced ER stress—the same effects that were reported for Sec62-depleted tumor cells.89–91 Hence, a treatment with CaM antagonists represents a potential mechanism how to achieve a functional SEC62 knockdown in a living organism and thereby inhibiting the migratory and proliferative potential of tumor cells. As TFP was used for the treatment of patients with psychiatric disorders over many years110 and one retrospective study observed a beneficial side effect of TFP treatment on the clinical course of tumor diseases,111 TFP appears to be a promising new substance for a targeted therapy approach, especially in tumors with high SEC62 expression levels. In addition, the observation that low Sec62 levels sensitize tumor cells to TG-induced ER stress68,89 is of potential clinical relevance. Over the past years, several in vitro and in vivo studies investigated the applicability of TG and TG prodrugs (G202 and 12ADT-Asp) for the treatment of cancer patients with promising results.112–114 In addition, a first clinical phase I trial including 44 patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors was finished in august 2013 (‘dose-escalation phase I study of G202 in patients with advanced solid tumors’, clinical trials gov. identifier NCT01056029) and reported an acceptable tolerability and favorable pharmacokinetic profile for G202, also called mipsagargin.115 For this treatment approach, Sec62 could serve as a predictive biomarker, as it was shown that high SEC62 expression levels attenuate the therapeutic efficacy of sarcoplasmic/ER Ca2+ ATPase inhibitors.68,89 With regard to the molecular background, a combined treatment of cancer cells with a sarcoplasmic/ER Ca2+ ATPase inhibitor and a CaM antagonist could overcome Sec62-mediated resistance and show synergistic therapeutic effects68—a new therapy approach that has to be evaluated in future studies.

Protein translocation complex as a target of bacterial toxins and small molecule therapeutics. Small molecules are written in italic and black letters; bacterial toxins in italic and green letters. The red arrows indicate inhibitory effects directed against the respective target structure. 40S, 40S ribosome subunit; 60S, 60S ribosome subunit; CaM, calmodulin; SERCA, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase.

Taken together, studies of the past decades have not only further illuminated the detailed mechanism of protein translocation into and across the ER membrane but gave also first insights into the role of proteins Sec61, Sec62 and Sec63 in human diseases including cancer, diabetes, liver and kidney diseases. Further investigations of the pathophysiological relevance of Sec proteins have the potential to provide a better understanding of disease emergence and progression, to enable a better prognostication and therapy planning in various cancer entities and to uncover new therapeutic targets.

References

Palade G . Intracellular aspects of the process of protein synthesis. Science 1975; 189: 347–358.

Zimmermann R, Eyrisch S, Ahmad M, Helms V . Protein translocation across the ER membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1808: 912–924.

Borgese N, Fasana E . Targeting pathways of C-tail-anchored proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1808: 937–946.

Rapoport TA, Rolls MM, Jungnickel B . Approaching the mechanism of protein transport across the ER membrane. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996; 8: 499–504.

Matlack KE, Mothes W, Rapoport TA . Protein translocation: tunnel vision. Cell 1998; 92: 381–390.

Schlenstedt G, Zimmermann R . Import of frog prepropeptide GLa into microsomes requires ATP but does not involve docking protein or ribosomes. EMBO J 1987; 6: 699–703.

Kutay U, Ahnert-Hilger G, Hartmann E, Wiedenmann B, Rapoport TA . Transport route for synaptobrevin via a novel pathway of insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. EMBO J 1995; 14: 217–223.

Walter P, Blobel G . Purification of a membrane-associated protein complex required for protein translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1980; 77: 7112–7116.

Walter P, Ibrahimi I, Blobel G . Translocation of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum. I. Signal recognition protein (SRP) binds to in-vitro-assembled polysomes synthesizing secretory protein. J Cell Biol 1981; 91: 545–550.

Görlich D, Rapoport TA . Protein translocation into proteoliposomes reconstituted from purified components of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Cell 1993; 75: 615–630.

Römisch K, Webb J, Herz J, Prehn S, Frank R, Vingron M et al. Homology of 54 K protein of signal-recognition particle, docking protein and two E. coli proteins with putative GTP-binding domains. Nature 1989; 340: 478–482.

Rapiejko PJ, Gilmore R . Empty site forms of the SRP54 and SR alpha GTPases mediate targeting of ribosome-nascent chain complexes to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 1997; 89: 703–713.

Mitra K, Frank J . A model for co-translational translocation: ribosome-regulated nascent polypeptide translocation at the protein-conducting channel. FEBS Lett 2006; 580: 3353–3360.

Tyedmers J, Lerner M, Wiedmann M, Volkmer J, Zimmermann R . Polypeptide-binding proteins mediate completion of co-translational protein translocation into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO Rep 2003; 4: 505–510.

Alder NN, Shen Y, Brodsky JL, Hendershot LM, Johnson AE . The molecular mechanisms underlying BiP-mediated gating of the Sec61 translocon of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 2005; 168: 389–399.

Dudek J, Benedix J, Cappel S, Greiner M, Jalal C, Müller L et al. Functions and pathologies of BiP and its interaction partners. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009; 66: 1556–1569.

Nguyen TH, Law DT, Williams DB . Binding protein BiP is required for translocation of secretory proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991; 88: 1565–1569.

Sanders SL, Schekman R . Polypeptide translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Biol Chem 1992; 267: 13791–13794.

Brodsky JL, Schekman R . A Sec63p-BiP complex from yeast is required for protein translocation in a reconstituted proteoliposome. J Cell Biol 1993; 123: 1355–1363.

Panzner S, Dreier L, Hartmann E, Kostka S, Rapoport TA . Posttranslational protein transport in yeast reconstituted with a purified complex of Sec proteins and Kar2p. Cell 1995; 81: 561–570.

Lyman SK, Schekman R . Interaction between BiP and Sec63p is required for the completion of protein translocation into the ER of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 1995; 131: 1163–1171.

Matlack KES, Plath K, Misselwitz B, Rapoport TA . Protein transport by purified yeast Sec complex and Kar2p without membranes. Science 1997; 277: 938–941.

Lang S, Benedix J, Fedeles SV, Schorr S, Schirra C, Schäuble N et al. Different effects of Sec61α, Sec62 and Sec63 depletion on transport of polypeptides into the endoplasmic reticulum of mammalian cells. J Cell Sci 2012; 125: 1958–1969.

Weitzmann A, Baldes C, Dudek J, Zimmermann R . The heat shock protein 70 molecular chaperone network in the pancreatic endoplasmic reticulum—a quantitative approach. FEBS J 2007; 274: 5175–5187.

Blobel G, Dobberstein B . Transfer of proteins across membranes. I. Presence of proteolytically processed and unprocessed nascent immunoglobulin light chains on membrane-bound ribosomes of murine myeloma. J Cell Biol 1975; 67: 835–851.

Knauer R, Lehle L . The oligosaccharyltransferase complex from yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999; 1426: 259–273.

Ng DT, Brown JD, Walter P . Signal sequences specify the targeting route to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Cell Biol 1996; 134: 169–178.

Schlenstedt G, Gudmundsson GH, Boman HG, Zimmermann R . A large presecretory protein translocates both cotranslationally, using signal recognition particle and ribosome, and post-translationally, without these ribonucleoparticles, when synthesized in the presence of mammalian microsomes. J Biol Chem 1990; 265: 13960–13968.

Sagstetter M, Zimmermann R . Assembly of M13 and M13am8H1R1 procoat protein into microsomes is stimulated by rabbit reticulocyte lysate and ATP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1988; 153: 498–501.

Wiech H, Stuart R, Zimmermann R . Role of cytosolic factors in the transport of proteins across membranes. Semin Cell Biol 1990; 1: 55–63.

Brodsky JL, Goeckeler J, Schekman R . BiP and Sec63p are required for both co- and posttranslational protein translocation into the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 9643–9646.

Abell BM, Pool MR, Schlenker O, Sinning I, High S . Signal recognition particle mediates post-translational targeting in eukaryotes. EMBO J 2004; 23: 2755–2764.

Lakkaraju AK, Thankappan R, Mary C, Garrison JL, Taunton J, Strub K . Efficient secretion of small proteins in mammalian cells relies on Sec62-dependent posttranslational translocation. Mol Biol Cell 2012; 23: 2712–2722.

Conti BJ, Devaraneni PK, Yang ZY, David LL, Skach WR . Cotranslational stabilization of Sec62/63 in the ER Sec61 translocon is controlled by distinct substrate-driven translocation events. Mol Cell 2015; 58: 269–283.

Tyedmers J, Lerner M, Bies C, Dudek J, Skowronek MH, Haas IG et al. Homologues of the yeast Sec complex subunits Sec62p and Sec63p are abundant proteins in dog pancreas microsomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 7214–7219.

Görlich D, Prehn S, Hartmann E, Kalies KU, Rapoport TA . A mammalian homolog of SEC61p and SECYp is associated with ribosomes and nascent polypeptides during translocation. Cell 1992; 71: 489–503.

Wirth A, Jung M, Bies C, Frien M, Tyedmers J, Zimmermann R et al. The Sec61p complex is a dynamic precursor activated channel. Mol Cell 2003; 12: 261–268.

Van den Berg B, Clemons Jr WM, Collinson I, Modis Y, Hartmann E, Harrison SC et al. X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel. Nature 2004; 427: 36–44.

Becker T, Bushan S, Jarasch A, Armache JP, Funes S, Jossinet F et al. Structure of monomeric yeast and mammalian Sec61 complexes interacting with the translating ribosome. Science 2009; 326: 1369–1373.

Pfeffer S, Dudek J, Gogala M, Schorr S, Linxweiler J, Lang S et al. Structure of the mammalian oligosaccharyl-transferase complex in the native ER protein translocon. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3072.

Pfeffer S, Burbaum L, Unverdorben P, Pech M, Chen Y, Zimmermann R et al. Structure of native Sec61 protein-conducting channel. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 8403.

Meyer HA, Grau H, Kraft R, Kostka S, Prehn S, Kalies KU et al. Mammalian Sec61 is associated with Sec62 and Sec63. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 14550–14557.

Müller L, de Escauriaza MD, Lajoie P, Theis M, Jung M, Müller A et al. Evolutionary gain of function for the ER membrane protein Sec62 from yeast to humans. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21: 891–903.

Rapoport TA . Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature 2007; 450: 663–669.

Rapoport TA . Protein transport across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. FEBS J 2008; 275: 4471–4478.

Hartmann E, Sommer T, Prehn S, Gorlich D, Jentsch S, Rapoport TA . Evolutionary conservation of commponents of the protein translocation complex. Nature 1994; 367: 654–657.

Deshaies RJ, Schekman R . SEC62 encodes a putative membrane protein required for protein translocation into the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 1989; 109: 2653–2664.

Deshaies RJ, Schekman R . Structural and functional dissection of Sec62p, a membrane-bound somponent of the yeast endoplasmic reticulum protein import machinery. Mol Cell Biol 1990; 10: 6024–6035.

Deshaies RJ, Sanders SL, Feldheim DA, Schekman R . Assembly of yeast Sec proteins involved in translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum into a membrane-bound multisubunit complex. Nature 1991; 349: 806–808.

Daimon M, Susa S, Suzuki K, Kato T, Yamatani K, Sasaki H . Identification of a human cDNA homologue to the Drosophila translocation protein 1 (Dtrp1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 230: 100–104.

Lyman SK, Schekman R . Binding of secretory precursor polypeptides to a translocon subcomplex is regulated by BiP. Cell 1997; 88: 85–96.

Plath K, Mothes W, Wilkinson BM, Stirling CJ, Rapoport TA . Signal sequence recognition in posttranslational protein transport across the yeast ER membrane. Cell 1998; 94: 795–807.

Schäuble N, Lang S, Jung M, Cappel S, Schorr S, Ulucan Ö et al. BiP-mediated closing of the Sec61 channel limits Ca2+ leakage from the ER. EMBO J 2012; 31: 3282–3296.

Simon SM, Blobel G . A protein-conducting channel in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 1991; 65: 371–380.

Lomax RB, Camello C, Van Coppenolle F, Petersen OH . Basal and physiological Ca2+ leak from the endoplasmic reticulum of pancreatic acinar cells. Second messenger-activated channels and translocons. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 26479–26485.

Roy A, Wonderlin WF . The permeability of the endoplasmic reticulum is dynamically coupled to protein synthesis. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 4397–4403.

Van Coppenolle F, Vanden Abeele F, Slomianny C, Flourakis M, Hesketh J, Dewailly E et al. Ribosome-translocon complex mediates calcium leakage fom endoplasmic reticulum stores. J Cell Sci 2004; 117: 4135–4142.

Flourakis M, Van Coppenolle F, Lehen’kyi V, Beck B, Skryma R . Passive calcium leak via translocon is a first step for iPLA2-pathway regulated store operated channels activation. FASEB J 2006; 20: 1215–1217.

Giunti R, Gamberucci A, Fulceri R, Banhegyi G . Both translocon and a cation channel are involved in the passive Ca2+ leak from the endoplasmic reticulum: a mechanistic study on rat liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys 2007; 462: 115–121.

Ong HL, Liu X, Sharma A, Hedge RS, Ambudkar IS . Intracellular Ca2+ release via the ER translocon activates store-operated calcium entry. Pflugers Arch 2007; 453: 797–808.

Wonderlin WF . Constitutive, translation-independent opening of the protein-conducting channel in the endoplasmic reticulum. Pflugers Arch 2009; 457: 917–930.

Wuytack F, Racymackers L, Missiaen L . Molecular physiology of the SERCA and SPCA pumps. Cell Calcium 2002; 32: 279–305.

Lang S, Erdmann F, Jung M, Wagner R, Cavaliè A, Zimmermann R . Sec61 complexes form ubiquitous ER Ca2+ leak channels. Channels 2011; 5: 228–235.

Erdmann F, Schäuble N, Lang S, Jung M, Honigmann A, Ahmad M et al. Interaction of calmodulin with Sec61α limits Ca2+ leakage from the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 2011; 30: 17–31.

Huang JB, Kindzelskii AL, Clark AJ, Petty HR . Identification of channels promoting calcium spikes and waves in HT1080 tumor cells: their apparent roles in cell motility and invasion. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 2482–2489.

Scorrano L, Oakes SA, Opferman JT, Cheng EH, Sorcinelli MD, Pozzan T et al. BAX and BAK regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: a control point for apoptosis. Science 2003; 300: 135–139.

Berridge MJ . The endoplasmic reticulum: a multifunctional signaling organelle. Cell Calcium 2002; 32: 235–249.

Linxweiler M, Schorr S, Schäuble N, Jung M, Linxweiler J, Langer F et al. Targeting cell migration and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response with calmodulin antagonists: a clinically tested small molecule phenocopy of SEC62 gene silencing in human tumor cells. BMC Cancer 2013; 13: 574.

Crowley KS, Liao S, Worrell VE, Reinhart GD, Johnson AE . Secretory proteins move through the endoplasmic reticulum membrane via an aqueous, gated pore. Cell 1994; 78: 461–471.

Walter P, Ron D . The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 2011; 33: 1081–1086.

Fumagalli F, Noack J, Bergmann TJ, Cebollero E, Pisoni GB, Fasana E et al. Translocon component Sec62 acts in endoplasmic reticulum turnover during stress recovery. Nat Cell Biol 18: 1173–1184.

Guerriero CJ, Brodsky JL . The delicate balance between secreted protein folding and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation in human physiology. Physiol Rev 2012; 92: 537–576.

Pisoni G, Molinari M . Five questions (with their answers) on ER-associated degradation. Traffic 2016; 17: 341–350.

Birgisdottir AB, Lamark T, Johansen T . The LIR motif—crucial for selective autophagy. J Cell Sci 2013; 126: 3237–3247.

Davila S, Furu L, Gharavi AG, Tin X, Onoe T, Qian Q et al. Mutations in SEC63 cause autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 575–577.

Drenth JP, Martina JA, van de Kerkhof R, Bonifacino JS, Jansen JB . Polycystic liver disease is a disorder of cotranslational protein processing. Trends Mol Med 2005; 11: 37–42.

Waanders E, te Morsche RHM, de Man RA, Jansen JBMJ, Drenth JPH . Extensive mutational analysis of PRKCSH and SEC63 broadens the spectrum of polycystic liver disease. Hum Mutat 2006; 27: 830.

Janssen MJ, Salomon J, te Morsche RHM, Drenth JPH . Loss of heterozygosity is present in SEC63 germline carriers eith polycystic liver disease. PLoS One 2012; 7: e50324.

Fedeles SV, Gallagher AR, Somlo S . Polycystin-1: a master regulator of intersecting cystic pathways. Trends Mol Med 2014; 20: 251–260.

Bolar NA, Golzio C, Živná M, Hayot G, Van Hemelrijk C, Schepers D et al. Heterozygous loss-of-function SEC61A1 mutations cause autosomal-dominant tubulo-interstitial and glomerulocystic kidney disease with anemia. Am J Hum Genet 2016; 99: 174–187.

Lloyd DJ, Wheeler MC, Gekakis N . A point mutation in Sec61α1 leads to diabetes and hepatosteatosis in mice. Diabetes 2010; 59: 460–470.

Mori Y, Sato F, Selaru FM, Olaru A, Perry K, Kimos MC et al. Instabilotyping reveals unique mutational spectra in microsatellite-unstable gastric cancer. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 3641–3645.

Schulmann K, Brasch FE, Kunstmann E, Engel C, Pagenstecher C, Vogelsang H et al. HNPCC-associated small bowel cancer: clinical and molecular characteristics. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 590–599.

Casper M, Weber SN, Kloor M, Müllenbach R, Grobholz R, Lammert F et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma as extracolonic manifestation of Lynch syndrome indicates SEC63 as potential target gene in hepatocarcinogenesis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 344–351.

Lu Z, Zhou L, Killela P, Rasheed AB, Di C, Poe WE et al. Glioblastoma proto-oncogene SEC61γ is required for tumor cell survival and response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 9105–9111.

Schuck S, Prinz WA, Thorn KS, Voss C, Walter P . Membrane expansion alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress independently of the unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol 2009; 187: 525–536.

Høyer-Hansen M, Jäättelä M . Connecting endoplasmic reticulum stress to autophagy by unfolded protein response and calcium. Cell Death Differ 2007; 14: 1576–1582.

Jung V, Kindich R, Kamradt J, Jung M, Müller M, Schulz WA et al. Genomic and expression analysis of the 3q25-q26 amplification unit reveals TLOC1/SEC62 as a probable target gene in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2006; 4: 169–176.

Greiner M, Kreutzer B, Jung V, Grobholz R, Hasenfus A, Stöhr RF et al. Silencing of the SEC62 gene inhibits migratory and invasive potential of various tumor cells. Int J Cancer 2011; 128: 2284–2295.

Linxweiler M, Linxweiler J, Barth M, Benedix J, Jung V, Kim YJ et al. Sec62 bridges the gap from 3q amplification to molecular cell biology in non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Pathol 2012; 180: 473–483.

Linxweiler M, Bochen F, Schick B, Wemmert S, Al Kadah B, Greiner M et al. Identification of SEC62 as a potential marker for 3q amplification and cellular migration in dysplastic cervical lesions. BMC Cancer 2016; 16: 676.

Wemmert S, Lindner Y, Linxweiler J, Wagenpfeil S, Bohle RM, Niewald M et al. Sec62 as a new biomarker for poor prognosis in advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2016; 11: 1661–1670.

Weng L, Du J, Zhou Q, Cheng B, Li J, Zhang D et al. Identification of cyclin B1 and Sec62 as biomarkers for recurrence in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Mol Cancer 2012; 11: 39.

Greiner M, Kreutzer B, Lang S, Jung V, Cavalié A, Unteregger G et al. Sec62 protein level is crucial for the ER stress tolerance of prostate cancer. Prostate 2011; 71: 1074–1083.

Heselmeyer K, Macville M, Schrock E, Blegen H, Hellstrom AC, Shah K et al. Advanced-stage cervical carcinomas are defined by a recurrent pattern of chromosomal aberrations revealing high genetic instability and a consistent gain of chromosome arm 3q. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1997; 19: 233–240.

Allen DG, White DJ, Hutchins AM, Scurry JP, Tabrizi SN, Garland SM et al. Progressive genetic aberrations detected by comparative genomic hybridization in squamous cell cervical cancer. Br J Cancer 2000; 83: 1659–1663.

Dehan E, Ben-Dor A, Liao W, Lipson D, Frimer H, Rienstein S et al. Chromosomal aberrations and gene expression profiles in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2007; 56: 175–184.

Chang YC, Yeh KT, Liu TC, Chang JG . Molecular cytogenetic characterization of esophageal cancer detected by comparative genomic hybridization. J Clin Lab Anal 2010; 24: 167–174.

Haverty PM, Hon LS, Kaminker JS, Chant J, Zhang Z . High-resolution analysis of copy number alterations and associated expression changes in ovarian tumors. BMC Med Genomics 2009; 2: 21.

Bockmühl U, Schwendel A, Dietel M, Petersen I . Distinct patterns of chromosomal alterations in high- and low-grade head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res 1996; 56: 5325–5329.

Sheu JJ, Lee CH, Ko JY, Tsao GS, Wu CC, Fang CY et al. Chromosome 3p12.3-p14.2 and 3q26.2-q26.32 are genomic markers for prognosis of advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 2709–2716.

Hagerstrand D, Tong A, Schumacher SE, Ilic N, Shen RR, Cheung HW et al. Systematic interrogation of 3q26 identifies TLOC1 and SKIL as cancer drivers. Cancer Discov 2013; 3: 1044–1057.

Zimmermann R, Müller L, Wullich B . Protein transport into the endoplasmic reticulum: mechanisms and pathologies. Trends Mol Med 2006; 12: 567–573.

Cross BCS, McKibbin C, Callan AC, Roboti P, Piacenti M, Rabu C et al. Eeyarestatin I inhibits Sec61-mediated protein translocation at the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci 2009; 122: 4393–4400.

Garrison JL, Kunkel EJ, Hedge RS, Taunton J . A substrate-specific inhibitor of protein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 2005; 436: 285–289.

Schäuble N, Cavalié A, Zimmermann R, Jung M . Interaction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exotoxin A with the human Sec61 complex suppresses passive calcium efflux from the endoplasmic reticulum. Channels 2014; 8: 76–83.

Baron L, Paatero AO, Morel JD, Impens F, Guenin-Macé L, Saint-Aurer S et al. Mycolactone subverts immunity by selectively blocking the Sec61 translocon. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 2885–2896.

McKenna M, Simmonds RE, High S . Mechanistic insights into the inhibition of Sec61-dependent co- and posttranslational translocation by mycolactone. J Cell Sci 2016; 129: 1404–1415.

Paatero AO, Kellosalo J, Dunyak BM, Almaliti J, Gestwicki JE, Gerwick WH et al. Apratoxin Kills Cells by Direct Blockade of the Sec61 Protein Translocation Channel. Cell Chem Biol 2016; 23: 561–566.

Carpenter Jr WT, Davis JM . Another view of the history of antipsychotic drug discovery and development. Mol Psychiatry 2012; 17: 1168–1173.

Zacharski LR, Moritz TE, Haakenson CM, O’Donnell JF, Ballard HS, Johnson GJ et al. Chronic calcium antagonist use in carcinoma of the lung and colon: a retrospective cohort observational study. Cancer Invest 1990; 8: 451–458.

Denmeade SR, Jakobsen CM, Janssen S, Khan SR, Garrett ES, Lilja H et al. Prostate-specific antigen-activated thapsigargin prodrug as targeted therapy for prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95: 990–1000.

Christensen SB, Skytte DM, Denmeade SR, Dionne C, Møller JV, Nissen P et al. A Trojan horse in drug development: targeting of thapsigargins towards prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2009; 9: 276–294.

Denmeade SR, Mhaka AM, Rosen DM, Brennen WN, Dalrymple S, Dach I et al. Engineering a prostate-specific membrane antigene-activated tumor endothelial cell prodrug for cancer therapy. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 140ra86.

Mahalingam D, Wilding G, Denmeade S, Sarantopoulas J, Cosgrove J, Cetnar J et al. Mipsagargin, a novel thapsigargin-based PSMA-activated prodrug: results of a first-in-man phase I clinical trial in patients with refractory, advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Br J Cancer 2016; 114: 986–994.

Acknowledgements

The assistance of Servier Medical Art for the design of the figures is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Linxweiler, M., Schick, B. & Zimmermann, R. Let’s talk about Secs: Sec61, Sec62 and Sec63 in signal transduction, oncology and personalized medicine. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2, 17002 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sigtrans.2017.2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sigtrans.2017.2

This article is cited by

-

Activation of ACLY by SEC63 deploys metabolic reprogramming to facilitate hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis upon endoplasmic reticulum stress

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2023)

-

Sec61γ is a vital protein in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane promoting tumor metastasis and invasion in lung adenocarcinoma

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

-

Analysis of differentially expressed genes in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus under heat stress

Acta Oceanologica Sinica (2023)

-

A comprehensive SARS-CoV-2–human protein–protein interactome reveals COVID-19 pathobiology and potential host therapeutic targets

Nature Biotechnology (2023)

-

Sec62 promotes gastric cancer metastasis through mediating UPR-induced autophagy activation

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2022)