Key Points

-

Describes a reduction in the job satisfaction of some GDPs following the implementation of new contractual arrangements in 2006.

-

Highlights a group of GDPs where a reduction in job satisfaction was most widely experienced.

-

Indicates that dentists' job satisfaction may have been impacted by a perceived erosion of professional autonomy.

Abstract

Objectives to measure changes in dental practitioners' job satisfaction following a contractual change, and compare differences between those transferring from a fee-per-item system (general dental service, GDS) and those previously working under a block contract with the primary care trust (personal dental service, PDS).

Design Analysis of postal questionnaires conducted in 2006 and 2007.

Participants Four hundred and forty dental practitioners responding to the 2006 baseline questionnaire.

Results Although perceived workload was unchanged, global job satisfaction had decreased for 24.7% (31) of GDS dentists and 49.0% (95) of PDS dentists comparing their scores given before and after the contractual change. PDS dentists showed a significant change in attitudes towards feeling restricted in providing quality care (change in factor mean [SD] = -2.88 [0.82]; p <0.001). They also showed less positive attitudes towards 'respect' (change in factor mean [SD] = -3.70 [0.48]; p <0.001).

Conclusions The 2006 contractual change appears to have had a negative impact on dentists' job satisfaction and has not addressed concerns which have led dentists to move into the private sector. The study indicates that the fall in job satisfaction is more a result of a perceived erosion of professional autonomy than a reaction to the change in the system of remuneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ever since the inception, in 1948, of National Health Service (NHS) dentistry delivered in general dental practice, practitioners have worked as independent contractors to the NHS, remunerated by a fee-per-item system. A steady drift of dental practitioners into the private sector,1 with attendant reported problems concerned with access to NHS dentistry,2 has brought the issue of the retention of the general dental practitioner (GDP) workforce onto the front pages of newspapers and to government attention.

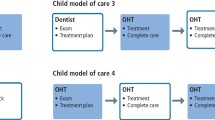

The fee-per-item system of remuneration was cited by the government as encouraging the move of dentists out of the NHS, as well as discouraging preventive dental care within the general dental practice system.3 A change in the system was seen as necessary and as a fore-runner to widespread reform, personal dental service (PDS) pilot arrangements were established.4 Over 6,000 dental practitioners voluntarily moved from the previous fee-per-item general dental service (GDS) system to a new system based on block contracts negotiated with the local primary care trust (PCT).5 Although national systems and guidelines were followed in the drawing up of contracts, there were local variations in the content of contracts, reflecting a move towards local commissioning. The dentists involved therefore experienced not just a change in the system of remuneration (and therefore incentives), but in governance, with increased accountability to the PCT.

The watershed in the system came on April 1 2006, when a new dental contract was introduced for all NHS dental practitioners, based on output targets of 'Units of Dental Activity' (UDAs). Both practitioners still working in the GDS and those working under PDS arrangements transferred to the new system. UDA targets set for GDS practitioners were based on activity during a reference period, less 5%.6 This 5% was intended to release the dental practitioner from the 'treatment treadmill' (based on the assumption that the previous fee-per-item system had been the driver to high levels of restorative care)7 in order to spend more time on preventive care for patients. Some within the profession, however, expressed scepticism that the new system would bring about a change in workload for practitioners, pointing out that with the average practitioner spending 60% of their time on NHS work, this represented one hour per week, which would probably be subsumed in additional administrative work.8

New contracts between PDS practitioners and the PCT were also drawn up, and while the new arrangements in terms of the system of remuneration (block contract) and governance (accountability to the PCT) were similar, the incentives within the new contract were different. UDA targets were introduced. The Department of Health did recognise that contracted activity levels in PDS agreements during the reference period were likely to be lower on average than for new GDS contracts, and gave guidance that a reduction of 15% in target UDA activity for previously PDS practices, compared to practices changing to the new system directly from the GDS fee-per-item system, might be expected.9 Certainly, before the change in the system in April 2006, PDS practitioners appear to have been under less workload pressure than their GDS counterparts at that time.10 So while the introduction of a remuneration system based on output (UDA) targets was new to both PDS and GDS practitioners, PDS practitioners were on the whole able to negotiate less stringent workload targets.

Job satisfaction is defined as 'the positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job or job experiences'.11 Interest in studying job satisfaction stems not only from a concern about the quality of life for employees, but also from a recognition that job satisfaction influences rates of retention of the workforce as well as productivity.12 Furthermore, since job satisfaction is known to affect behavioural intentions (and in the context of dental practice, this may include practitioner decisions about the geographic location of practice, practice type, office hours, and the clientele to be served),13 the potential impact on manpower is substantial. Shugars et al.14 suggest that job satisfaction is an important barometer for the dental profession, and that measures of job satisfaction can be used to identify problems or issues that can be targeted by dental schools and the profession, and to monitor providers' reactions to the changes in the organisation and financing of dental care. However, the second application here is relatively rare since previous research in this area is limited to single cross-sectional studies. Longitudinal studies or a series of cross-sectional studies would be more suited to this purpose.

Although the employment arrangements of GDPs do differ from general medical practitioners (GMPs), there are also many similarities. Like GDPs, GMPs have experienced successive changes to contractual arrangements and organisation of services in recent years, although the fluctuation in their job satisfaction has been well documented in a series of cross-sectional studies.15,16 A series of cross-sectional studies of GMP job satisfaction between 1987 and 2004 shows both rises and falls in job satisfaction, with the NHS reforms of 1990/1991 in general medical practice an apparent low point, associated with the 'imposition' of the 1990 GMP contract by the government being viewed as an attack on the 'independent' contractor status and professional autonomy of doctors.17 Given that primary care dentistry has undergone several similar changes in organisation, impacts seen in the level of practitioner job satisfaction might well be expected.

Workload has been identified as an important determinant of occupational stress among UK general dental practitioners, with 'time and scheduling demands' a consistent predictor of mental ill health in dentists.18 However, although an increase in 'time and scheduling demands' does appear to be related to dentists' job dissatisfaction, the relationship is weaker than might be expected.18 Investigation of changes in job satisfaction of UK dental practitioners in various work environments (GDS dentists and PDS dentists before the 2006 contractual changes), which differ according to workload demands as well as in their experience of changes in autonomy, creates an interesting setting in which to explore how these factors interact.

Changes in global job satisfaction scores are just one part of the picture. It is possible to be satisfied with some aspects of a job and at the same time be dissatisfied with others.19 The measurement of a number of discrete elements (or 'job facets') which contribute to job satisfaction allows the researcher to identify specific areas where job satisfaction is low, and consequently understand some of the causal mechanisms involved. Harris et al.20 identified six job satisfaction facets which were pertinent to UK dental practitioners: restriction in being able to deliver quality care; respect from being a dentist; control of work; running a dental practice; developing clinical skills; and helping others. Although some of these dimensions (such as 'respect') are common to other measures of dentists' job satisfaction,14 there are others (such as 'control') which are unique to this measure, developed in the context of UK dental practice. The development of the Harris dentist job satisfaction measure is reported elsewhere20 and involved a sample of GDPs working in 14 PCTs in three areas of England. The psychometric evaluation of the measure included testing for internal reliability (overall Cronbach's alpha = 0.88) as well as test-retest reliability (r = 0.78).

The aim of this study was to investigate changes in job satisfaction facets, and in overall job satisfaction, for previously PDS and previously GDS UK dental practitioners subsequent to the introduction of the new dental contract in April 2006. As such, it gives the opportunity to look at changes in the job satisfaction of dental practitioners associated with changes to incentives and governance arrangements. The study follows up dental practitioners who completed a job satisfaction measure before the contractual changes in 2006. This longitudinal study design, comparing job satisfaction of dentists' before and after the contractual changes, therefore allows some control for confounding factors unrelated to system changes.

Methods

Between January and March 2006, all GDPs (684) from a stratified sample of 14 PCTs were sent postal questionnaires. The PCT areas were selected to provide a balance between high and low disease levels, rural and urban areas and areas where a high or low proportion of GDPs had shifted from the GDS to the PDS system.20 Practitioners completed a global job satisfaction score using a five-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied) in response to a question 'How satisfied are you with your job?' They also completed a 40 item scale covering six job satisfaction facets. Table 1 lists the 40 attitudinal items identified following item analysis in the development of the questionnaire.20 Factor analysis was used to identify items which represent a common psychological construct, and Table 1 gives the items under the six factors identified in the analysis. Item loadings are a measure of how closely the statement is identified with the factor, with a high item loading being particularly closely identified with the factor. These six distinguishable job dimensions accounted for 52% of the variance in global job satisfaction.10 All items were written in a five-point Likert format (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Workload was measured as a response to a single question: 'a) I am not busy enough, I can meet a higher demand for care; b) I am neither not busy enough nor too busy and am able to meet the current demand for care; c) I am too busy and am not able to meet the demand for care.' Response rate was 65.2% (446), although there were six incomplete returns, leaving 440 for analysis.

In June 2007, the 440 respondents were sent another postal questionnaire containing the same measures of workload, global job satisfaction and job satisfaction attitudes. Before posting, questionnaires were labelled with an ID number to enable responses from the second wave to be associated with responses at baseline, on an individual basis. Analysis was undertaken using paired t-tests between GDP factor means at baseline and follow-up, and using the Wilcoxon test for changes in global job satisfaction and perceived workload. Multiple regression analysis was undertaken to identify personal and practice attributes significantly associated with changes in attitudes to the six job satisfaction facets. A stepwise forward selection model was used, where the most significant variables enter the model one by one until there are no other significant variables. Separate models were fitted for the six factors. Gender, single handed/multi-dentist practice, practice owner/associate, qualified before/after 1987 and whether the practice was previously a GDS practice, a PDS practice or had moved completely into the private sector since April 2006 were included as potential explanatory variables. Completely private practitioners before April 2006 were excluded from this analysis since numbers were low.

Results

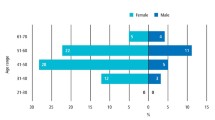

Sixteen of the 440 GDPs responding to the original questionnaire had retired or moved on. Response rate from the remainder was 79.5% (337), comprising 217 (64.4%) males and 120 (35.6%) females with a mean age of 42.7 years (SD = 9.54). Twenty-five (7.4%) of these were currently working completely in private practice, 262 (77.8%) in a mixture of NHS and private practice and 50 (14.8%) completely within the NHS. At baseline and follow-up, GDPs were asked to give an estimate of the percentage of their patients who they treated privately. GDPs working in the GDS previous to April 2006 reported a mean of 44.8% (SD = 36.42) private patients and 51.7% (SD = 38.6) afterwards. Previously PDS practitioners reported a mean of 15.0% (SD = 25.2) before and 20.7% (SD = 28.8) after the contract change. Between baseline and follow-up questionnaires, 20 GDPs had moved from the NHS or part NHS/part private practice completely into the private sector.

Table 2 shows the changes in global job satisfaction for three groups of practitioners: those who had worked in the NHS before April 2006 and now only undertake private work; practitioners who had previously worked in the GDS; and practitioners who had previously worked under PDS arrangements. Seven practitioners who were completely private at baseline were excluded from this and subsequent analyses. There was a significant decrease in global job satisfaction in both the GDS (p <0.024) and PDS groups (p <0.001). When the three-point scale of perceived workload completed at baseline was repeated, there were no significant differences in movement from a higher workload score (for example, 'I am too busy and am not able to meet the demand for care') to lower workload scores (for example, 'I am not busy enough, I can meet a higher demand for care') or vice versa for previously GDS (p >0.1) or previously PDS practitioners (p >0.1) (Table 3).

The study also identified changes in facets of job satisfaction. Table 1 gives the Cronbach alpha values for the factors as calculated for the measure as used at baseline. The psychometric properties of the measure in the follow-up questionnaire again indicated relatively high internal consistencies: restriction in being able to deliver quality care (α = 0.74), respect from being a dentist (α = 0.83), control of work (α = 0.84), running a dental practice (α = 0.84), developing clinical skills (α = 0.86), and helping others (α = 0.67).

Significant differences in some of the job satisfaction facets were identified when paired responses of practitioners (at baseline and follow-up) were compared, and differences were apparent between groups of practitioners (Table 4). The strength of feeling of the practitioner in relation to the factors is measured by the means from the response categories of all items in the factor, with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. A high mean score therefore signifies a more positive attitude to that factor. The attitude scale for negative statements such as 'I am not happy with my current work-rate' was reversed before the analysis so that a high mean score indicates a more positive attitude in all cases, including Factor 1. Changes in factor means which are negative therefore signify that practitioners hold less positive attitudes towards that factor than previously. While NHS practitioners who had moved completely into the private sector had significantly more positive attitudes to Factor 1 (restriction in being able to provide quality care, p <0.0001) and Factor 3 (control of work, p <0.05), no changes were evident for previously GDS practitioners. Practitioners previously working under PDS arrangements had less positive attitudes towards Factor 1 (p <0.05) and also Factor 2 (respect, p <0.001) following contractual changes.

When regression model analysis was carried out to explore the associations between the six factors and personal and practice characteristics, significant variables entered the model for only two of the factors (Factor 1: restriction in being able to provide quality care, and Factor 3: control of work). The Factor 1 model (Table 5) shows that both gender and time since qualification were significant factors in predicting change in attitudes. Female dentists and dentists who had been qualified more than 20 years showed a more negative change in attitudes (that is, becoming less satisfied) than male dentists and those who were qualified less than 20 years. Time since qualification also featured in the Factor 3 model (Table 6), indicating that dentists who had been qualified more than 20 years showed a more negative change in attitudes towards control of work than those qualified less than 20 years.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The shift away from NHS and into the private sector appears to have continued following the implementation of the new dental contract in April 2006. Both dentists who had been previously working in under GDS arrangements and those previously working in a PDS slightly increased their proportion of private patients, although this was to the same order of magnitude in both groups. Results indicate that job satisfaction has fallen for both previously GDS and previously PDS dentists when compared to data collected before the contractual change, although no significant reported shifts in workload were found. Examination of facets of job satisfaction reveal a difference between previously GDS and previously PDS practitioners, with previously PDS practitioners feeling more restricted in being able to provide quality care for their patients, and less respected, whereas for previously GDS practitioners no such findings are apparent.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Although the study sample was not a random sample of GDPs nationally, on account of a sampling grid being used to ensure samples were drawn from a range of different areas (for example, rural/urban), demographic characteristics of the sample such as age and proportion of female respondents indicate that the sample is characteristic of the UK GDP workforce, with the proportion of females in the sample (36%) being close to the figure of 39% females on the UK General Dental Council list at the end of 2007.21 However, the strength of the study is that this is not a series of cross-sectional studies but a longitudinal study, which means that apparent trends in job satisfaction associated with changes in response rate and characteristics of non-responders is not a concern. Job satisfaction among dental practitioners is known to be significantly associated with a shift towards private work20 and the differing case mix of NHS/private patients which may exist, and again a longitudinal study design is able to take account of differences between previously GDS and previously PDS practitioners in this respect, since increase in proportion of private work was relatively small and about the same size in both groups.

Comparisons with existing literature

One of the most interesting aspects of the study is finding that although workload was largely perceived as unchanged in both groups of dentists (previous GDS and previous PDS), both groups saw a decline in job satisfaction subsequent to the contractual change. A similar independence between workload and job satisfaction was seen in the series of cross-sectional studies of GMP job satisfaction,16 where although the 1990/1991 NHS reforms in general medical practice gave rise to an increase in medical practitioner workload which might have been expected to be an important impact of the reforms, contributing to the decline in job satisfaction, satisfaction with hours of work actually rose between 1987 and 1990.16 This supports previous findings that increase in the volume or complexity of work does not necessarily lead to lower job satisfaction if changes are accompanied by increased decision latitude (how work is to be accomplished).22

Certainly 'control of work' does appear to be an important contributor to job satisfaction for GDPs.20 Other research shows that for medical professionals, clinical autonomy is a more important determinant of job satisfaction than managerial autonomy.23 Several aspects of autonomy can be defined, ranging from clinical autonomy (relating to the patient-doctor interaction), to professional autonomy (professional self-government), to entrepreneurial autonomy (participating in the market as a small business).24 The items within the job satisfaction facet 'control' (Table 1) relate to a mixture of clinical and entrepreneurial autonomy. No significant change in attitude to this facet was found subsequent to contractual changes. However, previously PDS practitioners did show a more negative attitude towards the 'respect' facet. Items within this facet could be interpreted as relating to professional autonomy, and so this study indicates that while autonomy in clinical and business decision making may have been protected in the midst of changes in incentives and governance arrangements, an erosion of professional autonomy may have resulted in a deleterious effect on job satisfaction.

At baseline, more PDS practitioners (59.8%) working in wholly NHS practices or part NHS/part private practices (56.1%) felt satisfied or very satisfied with their job than GDS practitioners in completely NHS practices (46.2%), although this was less than GDS practitioners working in part NHS/part private practices (69.8%).10 This study suggests that for both PDS and GDS practitioners, job satisfaction has fallen since the introduction of contractual changes, although the changes appear to have had most impact among dentists who previously experienced the PDS system. This is contrary to what might be expected were changes in the system of remuneration (fee-per-item to block contract) to account for the decline in job satisfaction, since it was the GDS practitioners who experienced the greatest change in incentive structure. PDS practitioners merely shifted from a block contract to a block contract with activity targets. Changes in job satisfaction facets within the PDS group may reveal the area impacted by the changes. It suggests that practitioners felt an erosion of professional autonomy had occurred with the introduction of activity targets, causing them to feel more restricted in their ability to provide quality care for their patients. It is interesting to note that this was not on account of workload levels per se being increased. This is very much in line with the supposition that the NHS reforms in the GMP contract represented a low point in levels of job satisfaction among doctors because the contract was viewed as an attack on independent contractor status and professional autonomy.17

Implications of the study

The last decade has seen a succession of contractual changes for both dental and medical practitioners in the UK. Both groups have experienced changes in accountability to PCT commissioners as well as changes in incentive structures. This study suggests that contractual changes impacting on professional autonomy risk a negative impact on practitioner job satisfaction. In the case of dental practitioners, a further shift towards the private sector where fewer restrictions exist appears inevitable. Even within this study both PDS and GDS practitioners were found to further increase their proportion of private work, although there are no figures available to confirm whether this is a pattern replicated across the country. The lesson which seems to emerge from the study is that the way in which reforms are implemented, particularly in relation to perceived impacts on professional autonomy, may have a more powerful effect on job satisfaction than either workload or a change in incentive structure per se, and this may be something which policy makers both within dentistry and working in other fields of healthcare should bear in mind for the future.

References

Lynch M, Calnan M . The changing public/private mix in dentistry in the UK: a supply-side perspective. Health Econ 2003; 12: 309–321.

Harris R. Access to NHS dentistry in South Cheshire: a follow up of people using telephone help-lines to obtain NHS dental care. Br Dent J 2003; 195: 457–461.

Department of Health. Partial regulatory impact assessment on the draft National Health Service (General Dental Services Contracts) Regulations 2006. London: Department of Health, 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk/Publications.

National Health Service (Primary Care) Act 1997. London, HMSO, 1997.

Department of Health. NHS dentistry reform programme: update. Gateway reference 4449. London: Department of Health, 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk/ en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Dearcolleagueletters/DH_4104191.

Department of Health. Implementing local commissioning for primary care dentistry. Factsheet 1 - agreeing contracts with GDS dentists. Gateway reference 5917. London: Department of Health, 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/ Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/ DH_4124337.

Department of Health. Government announces next steps in reforms of NHS dentistry. Press release 2005/0241. London: Department of Health, 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Pressreleases/DH_4115007.

British Dental Association. BDA comments on the draft new GDS contract and PDS arrang ements regulations. London: British Dental Association, 2005.

Department of Health. Implementing local commissioning for primary care dentistry. Factsheet 2 - making new agreements with PDS dentists. Gateway reference 5917. London: Department of Health, 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk/ en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/ DH_4124337.

Harris R V, Ashcroft A, Burnside G, Dancer J M, Smith D, Grieveson B . Facets of job satisfaction of dental practitioners working in different organizational settings in England. Br Dent J 2008; 204: E1.

Locke E. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Dunnette M (ed) Handbook of industrial and organization psychology. Chicago: Rand McNally Co., 1976.

Sibbald B, Bojke C, Gravelle H . National survey of job satisfaction and retirement among general practitioners in England. BMJ 2003; 326: 22–24.

Wells A, Winter P A . Influence of practice and personal characteristics on dental job satisfaction. J Dent Educ 1999; 63: 805–812.

Shugars D A, DiMatteo R, Hays R D, Cretin S, Johnson J D . Professional satisfaction among California general dentists. J Dent Educ 1990; 54: 661–669.

Walley D, Bojke C, Gravelle H, Sibbald B . GP job satisfaction in view of contract reform: a national survey. Br J Gen Pract 2006; 56: 87–92.

Sibbald B, Enzer I, Cooper C, Rout U, Sutherland V . GP job satisfaction in 1987, 1990 and 1998: lessons for the future? Fam Pract 2000; 17: 364–371.

Sutherland V J, Cooper C L . Job stress, satisfaction, and mental health among general practitioners before and after introduction of the new contract. BMJ 1992; 304: 1545–1548.

Cooper C L, Watts J, Baglioni A J, Kelly M . Occupational stress among general practice dentists. J Occup Psychol 1988; 61: 163–174.

Herzberg F, Mauser B, Snydeman B B . The motivation to work. New York: Wiley, 1959.

Harris R V, Ashcroft A, Burnside G, Dancer J M, Smith D, Grieveson B . Measurement of attitudes of UK dental practitioners to core job constructs. Community Dent Health 2009; 26: 43–51.

General Dental Council. Annual report 2007. London: GDC, 2008. http://www.gdc-uk.org.

Karasek R A. Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Admin Sci 1979; 24: 285–308.

Lichenstein R L. The job satisfaction and retention of physicians in organized settings: a literature review. Med Care 1998; 41: 139–179.

Greer S. Medical autonomy: peeling the onion. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008; 13: 1–2.

Acknowledgements

Prior to the study NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained (05/MRE08/68). The University of Liverpool acted as Sponsor under the Department of Health Research Framework for Health and Social Care. NHS R&D approval was also obtained from the PCTs involved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, R., Burnside, G., Ashcroft, A. et al. Job satisfaction of dental practitioners before and after a change in incentives and governance: a longitudinal study. Br Dent J 207, E4 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.605

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.605

This article is cited by

-

Accreditation and professional integration experiences of internationally qualified dentists working in the United Kingdom

Human Resources for Health (2022)

-

Exploring dentists' professional behaviours reported in United Kingdom newspaper media

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Key determinants of health and wellbeing of dentists within the UK: a rapid review of over two decades of research

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Is organizational justice climate at the workplace associated with individual-level quality of care and organizational affective commitment? A multi-level, cross-sectional study on dentistry in Sweden

International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health (2018)

-

The policy context for skill mix in the National Health Service in the United Kingdom

British Dental Journal (2011)