Key Points

-

Informs readers why the number of children referred to hospital for dental treatment under general anaesthetic (GA) has been reported as increasing recently in England.

-

Explains why high caries risk cohorts of children are likely to experience further caries and subsequent treatment under GA.

-

Of interest to dentists and oral health policy-makers, the findings have implications for children treated under GA throughout the industrialised world.

Abstract

Introduction Despite overall improvements in oral health, the number of children admitted to hospital for extraction of teeth due to caries under general anaesthesia (GA) has been reported as increasing dramatically in England. The new UK government plans to transform NHS dentistry by improving oral health.

Aim To evaluate the dental care received by children who required caries-related extractions under GA and obtain the views of their parents or guardians on their experiences of oral health services and the support they would like to improve their child's oral health, to inform future planning.

Method An interview questionnaire was designed and piloted to collect data from a consecutive sample of 100 parents or guardians during their child's pre-operative assessment appointment. This took place at one London dental hospital between November 2009 and February 2010.

Results Most children were either white (43%) or black British (41%); the average age was seven years (range 2-15, SD 3.1, SE 0.31) and the female:male ratio was 6:5. Most (84%) had experienced dental pain and 66% were referred by a general dental practitioner (GDP). A large proportion of parents or guardians (47%) reported previous dental treatment under GA in their children or child's sibling/s. Challenges discussed by parents in supporting their child's oral health included parenting skills, child behaviour, peer pressure, insufficient time, the dental system and no plans for continuing care for their child. Three out of four parents (74%) reported that they would like support for their child's oral health. Sixty percent of all parents supported school/nursery programmes and 55% supported an oral health programme during their pre-assessment clinic.

Discussion These findings suggest that the oral health support received by high caries risk children is low. Health promotion programmes tailored to this cohort are necessary and our findings suggest that they would be welcomed by parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caries is a preventable disease and despite overall improvements in child oral health, the number of children (aged 16 years or under) admitted to hospital for extraction of teeth due to caries under general anaesthesia (GA) has been reported as increasing by 66% in England between 1997 and 2006.1 This exposes them to an increased risk of morbidity and mortality and has been a focus for recent BBC press coverage.2 Data from the British Association for Community Dentistry (BASCD) suggests that in five-year-olds between 1997/1998 and 2005/2006, DMFT (decayed/missing/filled teeth) remained at 1.47 and the care index (FT/DFT) decreased from 15% to 11%.3,4 More recent data suggest that child oral health may have improved further,5 although the results need to be treated with caution because of the potential impact of negative consent on participation in the survey. The above data suggest that less dental care is being provided in dental practice. Children referred for dental care under GA due to caries also have a high need for retreatment,6 which has considerable cost implications for the UK National Health Service (NHS).

The health manifesto for the Conservative Party recently elected to power in the UK in May 2010 includes an agenda to transform NHS dentistry by improving oral health and reducing the cost of remedial treatment. An initial proposal is to deliver preventive care incentives, screen and provide advice for five-year-olds and restore access to NHS dentistry.7 There is considerable existing literature on oral disease prevention such as the UK Department of Health guidance Delivering better oral health.8 Delivering oral hygiene and dietary advice to parents was shown to reduce severe early childhood caries in their children in one recent Australian randomised controlled trial,9 but prevention strategies for high caries risk children have not been planned as part of routine dental care. For these programmes to be successful, we must address the beliefs and attitudes of the child's parents or guardians, as these mediate the influences of culture on their child's oral health by affecting oral health behaviours.10,11,12 Future studies need to combine open and closed questions directed at parents or guardians to identify their views towards oral health services and complexities in stimulating behaviour change.13 In London, approximately 400-500 children per annum present to King's College Hospital Dental Paediatric and Day Case Unit for general anaesthetic requiring dental treatment under GA due to caries. This study aimed to evaluate the care these children had received to date and obtain the views of parents or legal guardians whose children required caries-related extractions under GA on the experience of oral health services and the support they would like to improve their child's oral health. This is intended to inform future planning for health services. The authors use the term parent to cover both parents and guardians throughout.

Method

An interview questionnaire was generated based on a review of current literature including the evidence base for preventive care,8,14,15 an audit conducted in Cardiff dental school, a pilot study and expert opinion. The service evaluation was registered as an audit with King's College Hospital. Open and closed questions were used in the interview questionnaire to collect data verbally from 109 consecutive parents during their child's pre-operative assessment appointment. Room for additional comments were available adjacent to each question. The questionnaire included a total of 33 questions including data on patient and child demography, parent's experience of their child's dental care to date and parent's attitudes towards health promotion. Table 1 provides a list of the questions used.

Interviews took place at King's College Hospital Dental Paediatric and Day Case Unit for general anaesthetic treatment between November 2009 and February 2010. Questionnaires were made anonymous using a hospital identification number. Parents with communication problems were interviewed using translators employed by the trust or a family relative. Quantitative data were entered into SPSS (SPSS for Windows, version 17.0, 2009) and analysed. Qualitative data (including additional comments made by parents throughout the interview) were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and categorised to provide a theoretical understanding.16

Results

One hundred and nine interviews were completed and 100 were included in the analyses because one parent declined interview due to time constraints and eight questionnaires were incomplete as some interviewees were unable to answer all questions during the interview time. This is approximately one quarter of the total number of children who attend the department annually for dental treatment under a GA due to caries.

Most children were either white (43%) or black British (41%); the remainder were Asian, Chinese or mixed. Some children (15%) had lived in another country previously. The average age of children was seven years (range 2-15, SD 3.1, SE 0.31) and the female:male ratio was 6:5. Some children (9%) had disabilities which may affect oral health and the most common were genetic defects affecting teeth. The majority of parents were mothers (82%); the remainders were fathers (15%) or others (3%), which included grandparents or siblings. A large proportion of parents were unemployed (32%); the remainder had professional/managerial/skilled non-manual (23%) or skilled manual (22%) or unskilled or partly skilled (20%) backgrounds.

The proportion of parents who reported a previous history of dental treatment for their child and/or other children under GA due to caries was 47%. This included 23% of children who were attending a pre-assessment appointment and in some cases an additional one (21%), two (7%) or three or four (6%) of their siblings. Parents reported that their children had mainly attended a dentist because of trouble (40%) or regularly within six months (38%). Others attended occasionally (14%), never (3%) or were unsure (5%). As a result of caries, children experienced an average of two problems or oral health impacts, often dental pain (84%), problems with chewing or talking (48%) and/or emotion (34%). These data are summarised in Figure 1. Oral health impacts due to caries were generally higher for children in lower socio-economic groups, as shown in Figure 2.

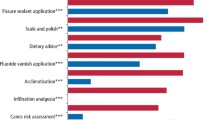

Most parents (72%) reported receiving previous oral health advice from a dentist on avoiding sugar and tooth brushing. Little advice was provided on fluoride toothpaste (45%) and fluoride mouth rinse (26%) or oral health interventions such as fissure sealants (10%) and fluoride varnish (8%). At school, 28% of children had participated in a tooth brushing programme, the remainder (64%) had not and eight parents (8%) were unsure. Three quarters were reported as being referred to the hospital by their general dental practitioner (GDP) and the remainder from a hospital dental professional (11%), Accident and Emergency (A&E) (4%), general medical practitioner (GMP) (7%) or community care (2%).

Many parents identified sweets, poor tooth brushing or a lack of oral health awareness as having led to caries. For example, in the words of one parent, 'I find it difficult to say no to my child when they ask for food or drink that is harmful to their teeth'. At home, 32 of the 59 children (54%) aged below seven years brushed their own teeth with no assistance from an adult. Several parents also mentioned that they had not been aware of the cause and prevention of caries. Parents reported that peer pressure (at school) and cultural factors (at home) strongly encouraged their child's sweet intake. For example, grandparents and siblings often provided them with sweets and these children also had easy access to sweets at school. Parents identified child behaviour as another challenge, for example difficulty encouraging their child to brush their teeth as many children 'refused to brush'. Finally, many parents identified time pressure as a factor in looking after their child's oral health due to long working hours and large families (the mean number of children in each family was three). Many parents (61%) had no plans for continuing dental care for their child; the remainder had follow-up appointments planned with a GDP (23%), hospital (13%) or community dental clinic (3%). Some parents (16%) reported difficulty accessing dental care, often because they could not find a local dentist or less often because their child was very anxious to have dental treatment.

The majority of parents (78%) requested support for their child's oral health such as a tooth brushing programme in school/nursery (60%) or an oral health programme at their pre-operative assessment clinic (55%). These data are shown in Figure 3a.

Parents often requested that this support be delivered during existing appointments, ideally from an early stage. However, if given only one choice, parents' preferences were spread over a range of interventions, with the highest proportion (28%) opting for a tooth brushing programme in school/nursery. This is shown in Figure 3b.

Parents with children who had had previous dental treatment under GA were more likely to ask for support, in particular oral health programmes at their pre-operative assessment appointment, tooth brushing programmes in school or nursery and other options which were similar. However, parents whose children were attending for their first dental treatment under GA were more likely to ask for support in the community, help finding a dentist, support at home or otherwise wanted no support or were unsure. This is shown in Figure 4.

When data are analysed based on socioeconomic status the majority of parents are non-professional and among these parents, all requested an oral health programme and most requested help in finding a dentist. Among parents from professional groups, these choices were less popular and more popular choices were not sure, do nothing and other similar options. This is shown in Figure 5.

When data are analysed based on parental knowledge, that is, how often they previously visited a dentist with their child, less regular attendees often requested do nothing, not sure, home visit and other options similar to home visits. Tooth brushing programmes in school and oral health programmes at the pre-operative assessment appointment received similar support but were slightly more popular among less regular attendees. For regular attendees, community support and help finding a dentist were the most popular options. This is shown in Figure 6.

Interestingly, among parents who asked for help in finding a dentist, most (57%) had been referred by a GDP and the remainder from hospital (29%) and A&E (14%). The former reported problems such as having no continuity of dentist and having received confusing advice. When asked which information they would like to help look after their child's teeth, most parents preferred advice in the form of a health professional (71%), website (64%) or leaflet (63%). Fewer requested a DVD (49%), telephone helpline (22%) or other (6%). Although a large proportion of parents (77%) had easy access to the internet, only 32% had used the internet to find out information on dental or general health. Many parents mentioned that information should be directed towards the child to make them better aware of how to promote their oral health. Most parents preferred health professionals to help discuss diet with the child (for example which foods are good and bad) or a DVD directed towards children which demonstrates how to brush their teeth. Others requested more support for schools, for example, tools for teachers to help them provide advice to pupils on how to look after teeth. Many also requested items such as toothpastes and toothbrushes which are recommended to best prevent caries. The majority of parents (64%) planned to stay at their current address for more than ten years and the average length of time parents had spent at a) their current address or b) in London and c) in the UK was seven years (range 0-32, SD 6.5, SE 0.66), 19 years (range 0-51, SD 13.7, SE 1.4) and 23 years (range 1-53, SD 12.9, SE 1.4) respectively.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the dental care received to date by children who required caries-related treatment under a GA and obtain the views of their parents on their experience of oral health services and the support they would like to improve their child's oral health. A key finding was that a need exists for novel interventions to improve oral health in this cohort of children and the majority of parents welcomed support to help look after their child's oral health. The demography of our sample is similar to that of the local resident population.17

All children in this study were at high caries risk, with the majority in the primary or mixed dentition phase. The UK Child Dental Health Survey 200318 reported that the decline in caries prevalence has plateaued in the primary dentition, despite it being a preventable disease. In this study, most parents (40%) reported little contact with a health professional and attended their dentist only when in trouble. Interestingly, some (38%) attended a dentist regularly but parents reported that preventive advice or health interventions had been poor, especially in relation to fluoride, despite its importance in preventing dental caries.8 As a likely consequence, the frequency of repeat GA in the children and their siblings from this study was 47%. A gradient also exists towards social deprivation in terms of caries-related oral health impacts and frequencies of repeat GA, but not all parents were socially deprived. These results identify a major public health issue, but this is not a unique problem and many studies outside London have shown similar results. For example, despite treatments involving multiple extractions or fillings under GA, the frequency of repeat GA in this patient cohort has been shown to be high13,19 due to inadequate preventive therapy.20 A Scottish multi-centre study in 2005 reported 25% of children having had a previous GA, rising to 48% in those aged nine years and above.6 Another study from Northern Ireland in 1998 reports 23%-31% of these children requiring further GA, with children aged below four years being at highest risk.21 Despite dealing with the immediate problem, these families require support in preventing further disease based on the strong evidence base outlined in Delivering better oral health.8 However, most parents in this audit had no plans for continuing dental care for their child. In addition, parents reported similar parenting challenges in supporting their child's oral health. These included difficulties refusing their child sweets, difficulties encouraging their child to brush and a lack of understanding of caries prevention. Similar qualitative studies from Canada and China have shown comparable findings.11,13 Other personal challenges included peer pressure and cultural factors and some parents suggested involving other family members when providing oral health advice. Previous research also recommends targeting dietary advice for children at the whole family.22 Another practical challenge expressed by parents was a lack of time due to long working hours and large families; the average number of children in a family in the UK was 1.8 in 2004, compared with 3 in this study.

All parents were keen to take part in interview and highlighted the importance of prevention, which suggests that the GA experience is likely to have motivated parents to improve their child's oral health practice in the short term. Most parents (78%) welcomed support to help look after their child's oral health but studies show that parents' perception of their ability to control factors such as tooth brushing and diet impacts on the establishment of favourable oral health behaviour in the long term.10,12 There is little in place to support longer-term maintenance of these positive early health behaviours10 and this will inevitably lead to further remedial treatment, especially in lower socioeconomic groups. Indeed, the current system is failing these patients and has huge cost implications for any health system. Evidence suggests that a dental system focused on prevention as opposed to curative treatments would save the NHS eight times the cost.23 The health manifesto for the Conservative Party newly elected to the UK government in May 2010 has set to incentivise preventive care in dentistry away from targets for fixed courses of treatment.7 An initial part of their proposal had been to screen and provide advice to children in schools at the age of five. Previous research indicates that the earlier preventive interventions are provided to children, the more likely they are to establish good oral health with less likelihood for restorative or emergency treatment.24 In addition, the average age of children in this study is similar (seven), over half of parents are settled locally and plan to remain at their current address for more than ten years and most welcome a range of health care interventions, in particular school-based programmes, so these new dental health care policies may be appropriate. Unfortunately, despite proposals to emphasise oral disease prevention in children,25 such programmes are now less likely and even if implemented, evidence suggests that unlike continued dedicated health programmes, one off screening is unlikely to achieve long term health outcomes.26 Therefore, dental health programmes, if initiated by the government, should be ongoing. In addition to school-based programmes, many parents in this study also favoured other programmes. Parents from lower socioeconomic groups with children who had attended for dental treatment under a GA previously favoured programmes at their pre-operative assessment appointment. Parents whose children were attending for their first appointment under GA were more likely to request help finding a dentist and local support in the community. Interestingly, parents who regularly attended a dentist with their child often requested help finding another dentist or help in the community, possibly due to a lack of support from their existing dentist. Finally, less regular attendees often did not have time to visit a dentist and were less likely to request help finding a dentist. Despite these positive suggestions, the authors are mindful of a recent Scottish study of parents of children from low socioeconomic groups whose children had had general anaesthetic for tooth extraction and who had a poor dental attendance history. This showed that follow up in the local Community Dental Service (CDS) clinics was disappointingly low, despite these parents previously asking for this support.27 Rather than simply finding these children a dentist or community support, a variety of novel family-centred oral health support tailored to this high caries risk cohort is therefore necessary. This should proactively combat the challenges faced by these families. Secondly, interventions that achieve better oral health outcomes should be innovative and build the evidence base, addressing the social determinants of health and working to give every child the best start in life in line with the Marmot review of inequalities (2010).28 Emerging national policies that emphasise prevention and focus on addressing inequalities in children's oral health are vitally important. Thirdly and as mentioned above, oral health programmes should be ongoing. Fourthly, advice and care should be consistent, evidence-informed, based on current Department of Health policy8 and family-centred. Examples of health promotion interventions other than health education include the use of fluoride, which is strongly supported by evidence to reduce caries incidence, for example, by using fluoride pellets that can be attached to the remaining dentition of high caries risk children.29 Lastly, it is important, as the government rightly points out, to incentivise dental care so that health promotion interventions are carried out by healthcare professionals in practice. Equally, for those children requiring dental treatment, appropriate treatment should be available in practice and alternatives to general anaesthesia should be explored where possible.20 Further work is necessary to address the effectiveness of oral health promotion interventions in delivering oral health improvements to this high caries risk cohort of children and their families.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the oral health support received by high caries risk children is low. Health promotion programmes tailored to this cohort are necessary and our findings suggest that they would be welcomed by parents.

References

Moles D R, Ashley P . Hospital admissions for dental care in children: England 1997-2006. Br Dent J 2009; 206: E14.

BBC. Preventable child illness reaches 'epidemic' levels. 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/panorama/hi/front_page/newsid_8615000/8615795.stm.

Pitts N B, Evans D J, Nugent Z J . The dental caries experience of 5-year-old children in the United Kingdom. Surveys co-ordinated by the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry in 1997/98. Community Dent Health 1999; 16: 50–56.

Pitts N B, Boyles J, Nugent Z J, Thomas N, Pine C M . The dental caries experience of 5-year-old children in Great Britain (2005/6). Surveys co-ordinated by the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Community Dent Health 2007; 24: 59–63.

NHS Dental Epidemiology Programme for England. Oral health survey of 5-year-old children 2007/08. Liverpool: North West Public Health Observatory and Centre for Public Health, 2009. http://www.nwph.net/dentalhealth/reports/NHS_DEP_for_England_OH_Survey_5yr_2007-08_Report.pdf

Macpherson L M, Pine C M, Tochel C, Burnside G, Hosey M T, Adair P . Factors influencing referral of children for dental extractions under general and local anaesthesia. Community Dent Health 2005; 22: 282–288.

Conservative Party. Transforming NHS dentistry: innovating for higher standards and greater access to care. London: Conservative Party, 2009.

Department of Health and the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention - second edition. London: Department of Health, 2009.

Plutzer K, Spencer A J . Efficacy of an oral health promotion intervention in the prevention of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008; 36: 335–346.

Pine C M, Adair P M, Nicoll A D et al. International comparisons of health inequalities in childhood dental caries. Community Dent Health 2004; 21: 121–130.

Wong D, Perez-Spiess S, Julliard K . Attitudes of Chinese parents toward the oral health of their children with caries: a qualitative study. Pediatr Dent 2005; 27: 505–512.

Adair P M, Pine C M, Burnside G et al. Familial and cultural perceptions and beliefs of oral hygiene and dietary practices among ethnically and socio-economicall diverse groups. Community Dent Health 2004; 21: 102–111.

Amin M S, Harrison R L . Understanding parents' oral health behaviors for their young children. Qual Health Res 2009; 19: 116–127.

Office for National Statistics. 2003 dental health survey of children and young people. London: Office for National Statistics, 2003.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Dental recall: recall interval between routine dental examinations. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N . Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000; 320: 114–116.

Office for National Statistics. Census area statistics; Southwark (local authority). London: ONS, 2010.

Lader D, Chadwick B, Chestnutt I et al. Children's dental health in the United Kingdom, 2003: Summary report. London: Office for National Statistics, 2003.

Sheller B, Williams B J, Hays K, Mancl L . Reasons for repeat dental treatment under general anesthesia for the healthy child. Paediatr Dent 2003; 25: 546–552.

Harrison M, Nutting L . Repeat general anaesthesia for paediatric dentistry. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 37–39.

MacCormac C, Kinirons M . Reasons for referral of children to a general anaesthetic service in Northern Ireland. Int J Paediatr Dent 1998; 8: 191–196.

Michela J L, Contento I R . Cognitive, motivational, social, and environmental influences on children's food choices. Health Psychol 1986; 5: 209–230.

Sharon S C, Connolly I M, Murphree K R . A review of the literature: the economic impact of preventive dental hygiene services. J Dent Hyg 2005; 79: 11.

Savage M F, Lee J Y, Kotch J B, Vann W F Jr . Early preventive dental visits: effects on subsequent utilization and costs. Pediatrics 2004; 114: e418–e423.

HM Government. Healthy lives, healthy people: our strategy for public health in England. London: The Stationery Office, 2010.

Worthington H V, Hill K B, Mooney J, Hamilton F A, Blinkhorn A S . A cluster randomized controlled trial of a dental health education program for 10-year-old children. J Public Health Dent 2001; 61: 22–27.

Hosey M T, Asbury A J, Bowman A W et al. The effect of transmucosal 0.2 mg/kg midazolam premedication on dental anxiety, anaesthetic induction and psychological morbidity in children undergoing general anaesthesia for tooth extraction. Br Dent J 2009; 207: E2.

Marmot M . Fair society, healthy lives. The Marmot review. London: The Marmot Review, 2010. http://www.marmotreview.org/AssetLibrary/pdfs/Reports/FairSocietyHealthyLives.pdf (accessed 14 April 2011).

Toumba K J, Curzon M E . A clinical trial of a slow-releasing fluoride device in children. Caries Res 2005; 39: 195–200.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Esther Hagan-Brown (Senior House Officer), Marie Parker (Head of Dental Nurse Continuing Professional Development) and all staff, parents and patients who supported and contributed to this study. The authors also wish to acknowledge the advice of Lesley Davis (Head of Dental Nursing) at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Finally, the authors acknowledge Anup Karki, SpR in DPH, Public Health Wales and Prof Ivor G. Chestnutt, Professor and Honorary Consultant in Dental Public Health, Cardiff University Dental School, who helped to develop the questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olley, R., Hosey, M., Renton, T. et al. Why are children still having preventable extractions under general anaesthetic? A service evaluation of the views of parents of a high caries risk group of children. Br Dent J 210, E13 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.313

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.313

This article is cited by

-

Are parents of high caries risk Dutch children motivated to brush their children’s teeth? An assessment using the health action process approach questionnaire

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2023)

-

Providing sealants at the general anaesthetic assessment visit for children requiring caries-related dental extractions under general anaesthetic: a pilot randomised controlled trial

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Childhood caries and hospital admissions in England: a reflection on preventive strategies

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Why do children still have preventable caries?

BDJ Team (2021)

-

A rapid review of variation in the use of dental general anaesthetics in children

British Dental Journal (2020)