Key Points

-

Shows the attitudes of specialists on the Dental Surgical Register to dental practitioners undertaking biopsies.

-

Indicates the views of dental practitioners on biopsy in practice and a need for more postgraduate training.

-

Suggests that current fees for biopsies undertaken in general practice are inadequate.

-

Reveals patients' worries about biopsy procedures.

Abstract

Aim To investigate biopsy procedures in general dental practice.

Objectives To assess the views and attitudes of: specialists on the dental specialist surgical registers; dentists in general practice (GDPs) and patients undergoing biopsy procedures.

Method Questionnaires were sent to 98 oral and maxillofacial surgeons and surgical dentists, 335 general dental practitioners and 220 patients attending the Oral Medicine Clinic at the Dental Hospital, Manchester. Participation rates were 68 (74%), 227 (72%), and 158 (76%) respectively.

Results Specialists: 47 (70%) would discourage dental practitioners undertaking biopsies. Concerns were a lack of skills and delays in referral; 20 (30%) considered GDPs should be able to perform simple biopsies for benign lesions. Dentists: 33 (15%) reported they had performed oral biopsies in the last two years; 136 (60%) felt they should be competent to biopsy benign lesions. Their main concerns were lack of practical skills and the risk of diagnostic error. Patients: 112 (65%) worried about their biopsy result, 67 (39%) would feel anxious if their dentist did the biopsy, although 40 (23%) were anxious when biopsied in the oral medicine clinic.

Conclusions Both specialists on the dental surgical registers and GDPs feel there is a need for further training in biopsy technique for GDPs and better advertised and accessible pathology support. The current fee for biopsies may need upward revision. A main concern of patients is fear of an adverse biopsy report. Whilst patients are satisfied with specialist management any concerns were an insufficient reason for biopsy of a benign lesion not being undertaken in general practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Previous reports on biopsy procedures in general dental practice demonstrate a small but steady increase in the number of specimens received by oral pathology departments.1 There are however conflicting findings on whether general dental practitioners (GDPs) should perform biopsies, and if so, for what lesions and when. Some claim GDPs should be competent to diagnose and biopsy the majority of oral lesion but stress that 'not innocent looking' lesions should be immediately referred.1 Others encourage GDPs to biopsy suspicious lesions thus assisting in the early detection of oral cancer.1,2,3,4,5 However surgeons may prefer to see oral lesions undisturbed by biopsy scars,6,7 although there is no detailed information on their views on biopsy by GDPs.

According to Schnetler8 and Leonard9 GDPs rarely see oral lesions requiring biopsy. This results in a lack of experience, unfamiliarity with the clinical patterns of oral malignancy, and may make them prone to referral. Many authors have repeatedly stressed the importance of postgraduate training through courses in oral medicine, diagnostic procedures and primary investigations.1,7,9 Although it is thought that GDPs prefer to refer the majority of oral lesions,10 there is no evidence on whether they may want to manage most oral lesions and whether they think postgraduate courses would help them to better deal with such lesions.

Patients could be a sensitive indicator for biopsies undertaken in general practice. They can recount experience and express a view on who should undertake this investigation. Patients however often associate the word biopsy with cancer,10 and this may mean they would prefer referral to a specialist.

Many factors may make a biopsy problematic and be reason for not undertaking it in general practice. These include: fear of medico-legal implications,5 unfamiliarity with biopsy technique,11,12 a lack of faith in personal diagnostic skills and the contention that biopsy is a specialist procedure.6 There is also concern that if the lesion proves to be malignant the GDP is not equipped to inform the patient they have cancer.10

To clarify current opinion, questionnaires were devised to obtain information on:

-

The views of those on the Dental Specialist Registers in oral surgery and surgical dentistry on whether GDPs should undertake biopsies.

-

Whether GDPs feel confident in performing oral biopsies and to look at barriers to the procedure.

-

How patients view a biopsy, and should their dentist undertake this?

Materials and methods

Views were obtained by postal questionnaires from 98 oral and maxillofacial surgeons and surgical dentists selected from the specialists' lists,13 335 general dental practitioners selected from the dentists' directories of the Manchester, Salford and Trafford Health Authorities14 and 220 patients attending the Oral Medicine Clinic at the University Dental Hospital, Manchester.

The Central Manchester Local Research Ethics Committee gave approval for the patient questionnaire. Dental records of 500 patients were examined to identify eligible patients. Patients with a definitive diagnosis of cancer, lichen planus, vesiculo-bullous disease, those who were referred by medical practitioners, self-referrals and patients under the age of 18 were excluded. All patients entered into the survey had been treated by the same specialist in surgical dentistry. Healing in all cases was uneventful.

A pilot study (15% of initial sample) was carried out on a random selection from each target group. A pre-paid envelope and covering letter were included in the mail shot. The majority of questions were partially close-ended and used tick boxes set against a ranked scale. Reminders were used to achieve a response rate of >66% for each target group.

The questionnaire sent to those on the Speciality Registers comprised 12 items. It was designed to obtain: a) demographic data including the gender and the year of initial qualification, b) personal opinion on a GDP's ability to recognize oral lesions and their referral patterns, c) views about GDPs undertaking biopsies and the surgeons' main concerns, d) perceptions on whether patients prefer biopsy as part of the specialist care, e) an open-ended question for suggestions.

The GDPs' questionnaire covered 26 items. It sought information on: a) demographic data including gender, qualifications, year of qualification and type of practice, b) soft tissue screening and referral patterns, c) experience of biopsies, d) previous learning of biopsy technique, e) views on whether GDPs should do biopsies, f) perceptions on how patients feel when a biopsy is advised g) problems encountered before, during and after biopsy. At the end there was an open-ended question.

The patients' questionnaire had 10 items seeking information on: a) the importance to them of their referral for biopsy, b) opinion on how they felt before and during the biopsy, c) who suggested the biopsy, d) the time elapsed between the referral and the biopsy report, e) satisfaction with specialist management, f) feelings if their dentist had performed the biopsy, g) an open-ended question for opinion or comment.

Data collected were entered into a Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 9.0) spreadsheet. Analysis included the use of descriptive statistics (frequencies, tables and charts) and statistical tests (χ2 test, or Mann-Whitney test). Significance was assessed at a level of α = 0.05. Power of the study was calculated in consultation with a statistician. For example 141 patient replies were required to test the hypothesis that 50% of patients will be anxious if their dentist performed the biopsy versus 35% (α = 0.05), power = 95%.

Results

The adjusted participation rates were 68 (74%) for the surgeons, 227 (72%) for the GDPs and 158 (76%) for the patient group. This was achieved after the exclusion of 'returned by the post-office undelivered'. The demographic findings are shown in detail in tables 1, 2, and 3. A total of 56 (82%) surgeons were male; 20 (29%) worked in oral and maxillofacial surgery, and 21 (31%) were registered in both surgical specialties. Of the GDPs 153 (67%) worked in the NHS, and 57 (25%) had a mixed practice: 123 (54%) had attended courses on oral surgery. In the patient group 106 (61%) were female and 75 (43%) did not know the meaning of biopsy before attending the specialist clinic. The need for a biopsy was first mentioned in 113 (65%) of cases during attendance at this clinic.

Surgeons' and dentists' views

There was general disagreement among surgeons, 42 (70%) would discourage GDPs from undertaking a biopsy, but 20 (30%) strongly believed GDPs should be able to perform simple biopsies for benign lesions, (polyps, papillomas, epulides, mucoceles, lipomas, etc) and undertaking excisional rather than incisional procedures. For patients with chronic problems, eg lichen planus, they considered biopsy in general practice would delay diagnosis and treatment. Few agreed that GDPs should biopsy white/red patches or ulcerative lesions.

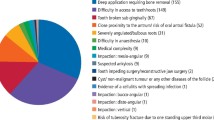

Main concerns (fig. 1) were of a GDP's inability to take a representative sample, delay should the biopsy report result in a referral and a perceived lack of technical expertise that might result in destruction of the original clinical picture. A major concern was the risk of diagnostic error. GDPs were thought to question their provisional diagnosis and to be afraid of possible misdiagnosis or serious pathology.

Sixty percent (136) of GDPs felt that they should be competent to perform biopsies (preferably excisional biopsies and exfoliative cytology). The main reasons for this were: a) a belief by 100 (74%) that this would help in reducing patient delay in the management of benign lesions and b) a claim by 83 (61%) that their patients would be less upset if treated by their own dentist. In contrast to the surgeons' views 49 (36%) felt biopsy by them could contribute to the early detection of cancerous lesions. A total of 57 (25%) dentists disagreed on being able to perform a biopsy and 34 (15%) made no judgement. However these latter groups both supported undertaking excisional biopsies in practice but felt incisional biopsies might be problematic and should be done by those undertaking follow-up. The GDP group's main concerns (fig. 2) were a lack of practical skills and the risk of diagnostic error, which accords with surgeons' concerns (fig. 1). Site and size of the biopsy specimen and spreading tumour cells during biopsy were further worries. Legal considerations relating to misdiagnosis or maltreatment were ranked third.

Following biopsy 137 (60%) GDPs perceived that a major limitation was materials and transport for histopathology. They appeared unaware that oral pathology departments can provide the necessary materials on request. Those aware of this policy added that it needed to be well advertised. The interpretation of the pathology report and postoperative management were also considered to be major problems by 90 (40%) GDPs.

Both surgeons and GDPs considered pay for the biopsy procedure as the least important factor although it was given a significantly lower rank value (Mann-Whitney p<0.001), by the surgeons.

Every 6 months 157 (69%) GDPs carried out an examination of the oral soft tissues, 25 (11%) carried it out once a year and 34 (15%) did this occasionally; 11 (5%) reported they only examined the teeth and the gums. Lesions requiring biopsy were seen by 104 (46%) GDPs annually and 75 (33%) detected lesions with a frequency of more than once a year. Some however claimed they saw lesions requiring biopsy monthly 42 (19%) or even weekly 3 (1.3%).

Fifteen percent (33) of dentists recorded that they had performed biopsies in the last two years (mainly excisional/aspiration and exfoliative biopsy). Only two GDPs undertook incisional biopsies.

Table 4 shows the overall management of lesions by GDPs; 88 (39%) said they had never been taught biopsy techniques while 138 (61%) reported they had. The majority, (86, 62%), were taught as undergraduates although 19 (14%) trained as postgraduates; 22 (16%) learnt how to biopsy from both undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Only 11 (8%) of the GDPs learnt biopsy techniques while they were working in dental practice (either as house officers in a hospital or dental school, or as associates in specialist dental clinics).

Both surgeons and dentists, as a first requirement, placed more training in oral medicine and basic biopsy techniques as essential if biopsy in general practice is to be facilitated (Table 5), the second requirement was good pathology support. Surgeons suggested practices should be provided with pots containing formalin and pre-paid specimen containers. GDPs proposed a collection service for specimens by a pathology courier laboratory, similar to the service for general medical practitioners, with links to oral medicine and oral surgery departments for advice. A colour-picture guide to lesions that should be biopsied in general practice was also thought to be helpful. Both surgeons and dentists suggested the current NHS biopsy fee needs revising. The surgeons perceived the fee as being too low and thus acting to discourage GDPs undertaking biopsies.

Patients' perceptions and attitudes

The majority of patients, 149 (85%), had several concerns (table 6) in respect of their biopsy although 26 (15%) had no worries. Those who worried if the results would reveal anything serious or sinister (cancer) totalled 113 (64%), 67 (39%) reported they would feel anxious if their dentist undertook their biopsy. Significantly fewer, 40 (23%) (p<0.001 McNemar test) reported anxiety when their biopsy was carried out in the oral medicine clinic, although they were reassured about the possible favourable outcome by hospital staff both at consultation and the biopsy appointment. Patients repeatedly commented that their concern was of technical competence no matter who performed the biopsy.

The majority (139, 80%) of the patients stated they were very satisfied with specialist management, 32 (18%) were simply satisfied. Referral to the oral medicine clinic was perceived as very important by 76 (44%) patients, as important by 58 (33%), whilst for 21% it was moderately important and for 2% unimportant or unnecessary. Thirty-eight (58%) surgeons perceived that patients always felt reassured when referred to a specialist for biopsy. A total of 124 (55%) dentists also perceived that after a lengthy discussion their patients were usually happy to be referred to specialists. However 30 (13%) of dentists considered that if there were no worries patients would prefer their biopsy in general practice since it was quicker and avoids travel to the specialist centre.

The time between the biopsy and notification of the result was perceived to be short for 80 (47%) patients; 30 (17%) could not remember, whilst 16 (9%) thought it was very short. In contrast 26 (15%) considered the time to be long and 9 (5%) said it was too long.

Discussion

In 1955 Boyle21 commented that an individual's qualifications have little to do with ability to perform a biopsy. His words appear valid today since the issue of who should biopsy remains controversial. This study involved three different groups in order to obtain a broad picture on the optimum approach to oral biopsies. There are few similar studies. Related questionnaire-based surveys have been more limited, have involved only GDPs or are reviews of specimens submitted to pathology laboratories. Response rates varied widely. Payne16 had a 71% response rate in a survey of dentists, Cowan et al.17 a 67% response, but Warnakulasuriya and Johnson7 achieved only a 16% response.

Biopsy is of paramount importance because it is strongly related to the early detection of oral cancer.4 A GDP's reluctance to perform a biopsy can mainly be attributed to a possible misdiagnosis of malignancy or serious pathology and risk of litigation. GDPs are often unfamiliar with the different clinical patterns of oral malignancy since they rarely see an oral carcinoma.8 Although some dentists prefer to refer oral lesions to specialists, the GDP is qualified to perform routine biopsies for submission to a qualified pathologist.7 It seems paradoxical that GDPs will render a patient edentulous yet hesitate to remove a few millimetres of soft tissue.2

There are however a plethora of legal implications regarding biopsy procedures and legal action is becoming more prevalent in the UK. It is claimed that a dentist's responsibility is to recognize oral lesions, to inform the patient of them and to provide treatment or ensure referral.5 As a result, failure to refer the patient for diagnosis or treatment is also negligent. Dentists can also be liable to prosecution when they do not conform to Health and Safety regulations governing packaging and transportation of biopsy specimens.19,20

When undertaking a biopsy, practical competence, the ability to distinguish a benign from the pre/malignant or malignant lesion, and correct patient management, are the points at issue. However referral is only beneficial when it is prompt and indicated. Early referral is crucial when malignancy is suspected.

There are conflicting findings with regard to the promptness of referral and the degree of urgency stated in the referral letters. Standards of referral letters have been reported both as inadequate,8,21 and good.21,22 In one study8 most referral letters did not imply a sufficient degree of urgency for immediate action to be taken by the consultant. In a study by Zakrzewska21 more than 50% of the referral letters did not include a provisional diagnosis. In this study the majority of oral surgeons (55, 83%) judged the degree of urgency reflected in referrals as good or reasonably good, although it was considered bad by 8 (12%). The surgeons also perceived that dentists were better at diagnosing benign lesions compared with premalignant or malignant ones.

Of the dentists in this study, 33 (15%) had performed oral biopsies (mainly excisional) in the last two years. The GDPs who had been taught how to biopsy were significantly more likely to undertake biopsies in general practice (χ2 test, p<0.001). This finding is similar to that previously reported.11,16 Warnakulasuriya and Johnson7 found that 21% of general dentists performed biopsies in 1991 in the UK. However the low response (16%) could have biased the result. Cowan et al.17 reported that only a proportion (12%) of dentists attempted to biopsy in Northern Ireland, whereas Berge23 found that 56% of dentists offer biopsy in Norway. Norway however has a poor supply of oral surgery services and consequently dentists are forced to perform a wider range of procedures.

The importance of postgraduate training provided courses on oral medicine and diagnostic procedures for general practice has been repeatedly mentioned.1,7,9 In the study by Coulthard et al.23 70% of dentists stated they wanted more involvement in their patients' specialist management suggesting little has changed since a questionnaire-based survey of 1998 that reported only 21% of recently qualified dentists felt well prepared to offer biopsy after graduation.24

In order to help GDPs detect suspicious oral lesions screening systems such as exfoliative cytology and the use of tolonium chloride (OraTest)25 for high-risk patients have been suggested. However both methods of screening, before biopsy, are not a panacea since they can provide false negative (exfoliative cytology) or false positive (toluidine blue) results. Brush biopsy, another suggested method of oral mucosal screening, is also advertised for use in general dental practice.26 However a thorough examination with two dental mirrors and a high index of suspicion are still the key factors in the recognition of any abnormality in the oral cavity.

The literature suggests that oral mucosal screening can realistically be carried out as an integral part of routine dental care.27 Cowan et al.17 found that 94% of dentists regularly examine the oral soft tissues for potentially malignant lesions. In our study 157 (69%) dentists reported carrying out examination of the oral soft tissues every 6 months whilst 25 (11%) carried it out annually. According to Warnakulasuriya and Johnson7 12% of GDPs occasionally examine the oral mucosa if there is reason to suspect a lesion. In our study 34 (15%) GDPs visually screened the oral mucosa only occasionally, with 5% never examining the oral mucosa. Some of these findings are disappointing considering the GDC requirement in the dental curriculum for undergraduates to be taught the clinical presentation, diagnosis and management of the common diseases of the oral mucosa.28 In contrast two practitioners stated they screened the oral mucosa once a year for many patients (mainly the edentulous) with toluidine blue (OraTest).25

If the GDP is to be encouraged to undertake biopsies it is necessary to be certain that patients will be examined to the same standard as in a specialist centre. Although the above evidence suggests most dentists routinely examine the oral mucosa one still wonders how effective this preventive examination is.

In this study, 125 (55%) dentists reported that they referred without any investigations while 68 (30%) reviewed lesions and then referred if necessary. For 31 (15%) GDPs the policy was review and/or investigation/treatment and then referral. The relatively close proximity of the study sample to the dental school may have influenced referral. In Warnakulasuriya and Johnson's study7 74% of dentists were found to refer without further investigations.

A lack of information about pathology services was of major concern to both surgeons and GDPs. Similar concerns have been raised regarding oral microbiology laboratory services where a lack of information was the biggest problem (70% of GDPs).29 It was considered unlikely that the provision of a laboratory handbook alone would change behaviour, with follow through education and development being needed. GDPs received a fee of £7.90 for microbiological sampling, this fee was considered inadequate by the few aware of it. It seems the same situation exists regarding biopsies. In our study both dentists and surgeons recommended revision of the current NHS fee (£8.90).

Although GDPs thought they should be competent to perform both excisional biopsies and exfoliative cytology, surgeons were reluctant to encourage biopsies in general dental practice. Some surgeons raised the issue that the advent of surgical dentistry might mean patients would be better managed in specialist practice and only referred to the hospital service when indicated. Patients worried about their biopsy outcome but were generally satisfied with specialist management. They considered however that if their dentist did biopsies they would accept having their biopsy in general practice. Dentists therefore ought to know not only what, where, when and how to biopsy, but also when to refer and how to manage the subsequent report. Maybe there is no longer a need to wonder whether GDPs should biopsy since each decision is dependent on dentists' individual skills, responsibility, and continuing education in the management of their patients.

Conclusions

-

GDPs should be competent in performing simple biopsies for benign lesions regardless of whether they prefer to biopsy or to refer. This is what oral surgeons would expect and what many dentists would prefer.

-

Excision biopsies and non-invasive diagnostic procedures such as swabs and smears could be more easily undertaken in general dental practice in the near future. Suspicious lesions are better referred to specialists for further management.

-

Further training in distinguishing the benign oral lesions from the pre/malignant ones and in biopsy techniques is fundamental for the success of the above.

-

Good pathology support is essential and in particular needs to be well advertised to the general dental practitioners. The current NHS fee for biopsies may need to be revised.

-

Overall patients appear to be satisfied with specialist management. Their main concern is fear of an adverse biopsy report. However any concerns do not appear overall to be sufficient reason why a biopsy (of a benign lesion) should not be undertaken in general practice. Such a change would benefit patients by reducing delays and travel costs and would result in the more effective and efficient use of specialist clinics.

References

Williams HK, Hey AA, Browne RM . The use by general dental practitioners of an oral pathology diagnostic service over a 20-year period: the Birmingham Dental Hospital experience. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 424–429.

Myall RW, Howell RM . A rational approach to biopsy. J Oral Med 1971; 26: 71–74.

Bramley PA, Smith CJ . Oral cancer and precancer: establishing a diagnosis. Br Dent J 1990; 168: 103–107.

Porter SR, Scully C . Early detection of oral cancer in the practice. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 72–73.

Marder MZ . The standard of care for oral diagnosis as it relates to oral cancer. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1998; 19: 569–582.

McAndrew PG . Oral cancer biopsy in general practice letter. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 428.

Warnakulasuriya KAAS, Johnson NW . Dentists and oral cancer prevention in the UK: opinions, attitudes and practices to screening for mucosal lesions and to counselling patients on tobacco and alcohol use: baseline data from 1991. Oral Dis 1999; 5: 10–14.

Schnetler J F C . Oral cancer diagnosis and delays in referral. Br J Oral Maxillof Surg 1992; 30: 210–213.

Leonard MS . Biopsy issues and procedures. Dent Today 1995; 14: 50–55.

Cawson RA, Odell EW Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine. 6th Ed 1998 London: Churchill Livingstone Publications.

Margarone JE, Natiella JR, Natiella RR . Primates as a teaching model for biopsy. J Dent Educ 1984; 48: 568–570.

Bonner P . Biopsy – An essential diagnostic tool. Dent Today 1998; 17: 83–85.

The Specialist Lists General Dental Council 1999.

Dentists Directories Manchester Salford and Trafford Areas General Dental Council 1999.

Boyle PE . Who should take the biopsy? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 1955; 8: 118–122.

Payne TF . The utilization of diagnostic techniques-a survey of 714 dentists. J Oral Med 1977; 32: 121–122.

Cowan CG, Gregg TA, Kee F . Prevention and detection of oral cancer: the views of primary care dentists in Northern Ireland. Br Dent J 1995; 179: 338–342.

Lovas J, Loyens S . The dentist, the biopsy and the law. J Canad Dent Assoc 1985; 51: 29–31.

The rules governing postal transfer of pathology specimens are contained in The Inland Postal Services: Prohibitions 1987. Copies can be obtained through any post office.

James C . Pathology specimens through the post-how to avoid prosecution. J Med Defen Union 1988; 4: 19.

Zakrzewska JM . Referral letters-how to improve them. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 180–182.

McAndrew R, Potts AJC, McAndrew M, Adam S . Opinions of the dental consultants on the standard of referral letters in dentistry. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 22–25.

Coulthard P, Kazakou I, Koran R, Worthington HV . Referral patterns and the referral system for oral surgery care. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 388–391.

Greenwood LF, Lewis DW, Burgess RC . How competent do our graduates feel? J Dent Educ 1998; 62: 307–313.

BDA occasional paper. Opportunistic Oral Cancer Screening. British Dental Association 2000 6.

The Probe September 2000; 42: No 20.

Field EA, Darling AE, Zakrzewska JM . Oral mucosal screening as an integral part of routine dental care. Br Dent J 1995; 179: 262–266.

The First Five Years The Undergraduate Dental Curriculum. The General Dental Council 1997.

Roy KM, Smith A, Sanderson J et al. Barriers to the use of a diagnostic oral microbiology laboratory by general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 345–347.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to take the opportunity to thank all the oral surgeons, dentists and patients who returned the questionnaires and made the completion of this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diamanti, N., Duxbury, A., Ariyaratnam, S. et al. Attitudes to biopsy procedures in general dental practice. Br Dent J 192, 588–592 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801434

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801434

This article is cited by

-

Machine learning in the detection of dental cyst, tumor, and abscess lesions

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Experiences, perceptions, and decision-making capacity towards oral biopsy among dental students and dentists

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Diagnostic accuracy of clinical visualization and light-based tests in precancerous and cancerous lesions of the oral cavity and oropharynx: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Clinical Oral Investigations (2021)

-

Perspectives of San Juan healthcare practitioners on the detection deficit in oral premalignant and early cancers in Puerto Rico: a qualitative research study

BMC Public Health (2011)

-

Patient choice of primary care practitioner for orofacial symptoms

British Dental Journal (2008)