Key Points

-

Incisional drainage is the first principle in management of acute dentoalveolar infection.

-

Penicillin-resistant bacteria are often present in acute dental infection.

-

The presence of penicillin resistant bacteria does not adversely affect the outcome of treatment even if penicillin is prescribed.

-

It is likely that antibiotic therapy is often prescribed unnecessarily in treatment of acute dental infection.

Abstract

Objectives The aim of this audit was to measure the outcome of treatment of acute dentoalveolar infection and to determine if this was influenced by choice of antibiotic therapy or the presence of penicillin-resistance.

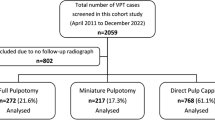

Subjects and methods A total of 112 patients with dentoalveolar infection were included in the audit. All patients underwent drainage, either incisional (n=105) or opening of the pulp chamber (n=7) supplemented with antibiotic therapy. A pus specimen was obtained from each patient for culture and susceptibility. Clinical signs and symptoms were recorded at the time of first presentation and re-evaluated after 48 or 72 h.

Results A total of 104 (99%) of the patients who underwent incisional drainage exhibited improvement after 72 h. Signs and symptoms also improved in five of the seven patients who underwent drainage by opening of the root canal although the degree of improvement was less than that achieved by incisional drainage. Penicillin-resistant bacteria were found in 42 (38%) of the 112 patients in this study. Of the 65 patients who were given penicillin, 28 had penicillin-resistant bacteria. There was no statistical difference in the clinical outcome with regard to the antibiotic prescribed and the presence of penicillin-resistant bacteria. Strains of penicillin-resistant bacteria were isolated more frequently in patients who had previously received penicillin (p<0.05).

Conclusion Incisional drainage appeared to produce a more rapid improvement compared to drainage by opening of the root canal. The presence of penicillin-resistant bacteria did not adversely affect the outcome of treatment. The observations made support surgical drainage as the first principle of management and question the value of prescribing penicillin as part of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of dentoalveolar infections are related to necrotic dental pulp tissue.1 Most acute infections are mild and can be managed by simple local therapy alone involving the establishment of surgical drainage. Drainage, which can be achieved by tooth extraction, surgical incision or through root canal, is the most important factor in treatment of dentoalveolar infections.1,2,3,4,5 However, occasions do arise when systemic antibiotic may need to be prescribed in addition to drainage in order to limit spread of infection and prevent the onset of serious complications.1,2,3,4,5,6 Although the choice of antibiotic therapy in these circumstances should be based on the result of microbiological investigation of pus from the infection, this information is not available for several days and prompt delivery of specimens to the laboratory is rarely feasible in a general dental practice setting.2,6 Therefore, an antimicrobial agent is usually prescribed empirically.2,6 Members of the penicillin group of antibiotics have long been the first-line antibiotics for dental infections due to a suitable antimicrobial activity, low incidence of adverse effects and good cost-effectiveness.1,2,3,4,5,6

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the causative bacteria is one of the factors that could affect the clinical impact of antibiotic therapy prescribed.1,2,3,4,5,6,78 In the past 10 years, the incidence of penicillin resistance in odontogenic infections in the UK has increased from 5% to 55%.7,8 This increase has brought into question the appropriateness of penicillin when it is felt the patient's clinical symptoms indicate a need for antibiotic therapy as part of the management of dental infections.4 In addition, the presence of penicillin-resistant bacteria in dental infections has been implicated as the cause of clinical failure of penicillin in some cases.5 Furthermore, it has been suggested that the presence of penicillin-resistant bacteria in dental infections is related to previous exposure to penicillin therapy.6,9,10

The aim of the present audit was to determine if the outcome of treatment of dentoalveolar infection was influenced by the choice of the antibiotic and the presence of penicillin-resistant bacteria. A second objective was to determine any correlation between the presence of antibiotic-resistance within the infection and a history of previous antibiotic therapy.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

A total of 112 patients (88 males and 24 females) with an average age 37.1 years (range 17 – 81) who had acute dentoalveolar infection and were treated as out-patients in the Examination and Emergency Clinic at the University Dental Hospital and School in Cardiff between January 1999 and January 2003 were investigated. Patients were excluded if they suffered from any immunosuppressive disease or were taking a medicine that could suppress the immunity, if the abscess was already draining, if it was not possible to obtain an appropriate pus specimen or if systemic antibiotic was not necessary. Pregnant patients were also excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Pre-treatment clinical assessment

A proforma recording previous dental and medical history including receipt of any antibiotic in the preceding six months and analgesic therapy was completed for each patient. All patients were examined to confirm the diagnosis and establish which tooth was involved. Clinical signs and symptoms that were recorded included presence of pain, extra-oral and intra-oral swelling and body (aural) temperature.

Treatment

All patients underwent surgical drainage either by incision of soft tissue swelling or by opening into the pulp chamber. A pus specimen was obtained by sterile needle aspiration prior to the incision of any swelling. If drainage was achieved by opening into the pulp chamber, a sample of pus was obtained by a swab of the exudate from the root canal. Pus specimens were transferred promptly to the microbiological laboratory within the hospital and processed within three hours. Each patient was provided with a systemic antibiotic regimen as determined most appropriate by the clinician.

Microbiological culture

All pus specimens were inoculated onto Fastidious Anaerobe Agar (LabM, Bury, UK) supplemented with 5% v/v horse blood, which was incubated in an anaerobic chamber at 37°C for 48 h. Pus was also inoculated onto plates of blood agar (LabM) and chocolate agar, which were incubated under an aerobic and a micro-aerophilic atmosphere respectively at 37°C for 48 h. Isolates were identified by conventional methods.11 Antimicrobial susceptibility of all isolates to penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, metronidazole and clindamycin was determined by a disk diffusion method according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards.12

Post-treatment clinical assessment

Clinical signs and symptoms were reassessed by the same clinician (EGA) after either 48 h or 72 h. A clinical score was used to evaluate the patient's perception of efficacy of treatment and overall improvement. The four-point clinical scale used at the review appointment was as follows:

3 – Completely improved (complete resolution, absence of any signs and symptoms)

2 – Much improved (almost complete resolution but mild signs and symptoms remained)

1 – Slightly improved (the intensity of signs and symptoms slightly reduced)

0 – No improvement (the intensity of signs and symptoms remained the same).

Statistical analysis

Student-T analysis was used for the comparison of clinical improvement scores. Statistical comparison of prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria was performed by a Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test.

Results

Signs and symptoms of patients at the first presentation

A total of 110 patients (98%) presented with a complaint of spontaneous pain. Ninety-seven (87%) patients exhibited extra-oral swelling in either the canine, submandibular or buccal space. No patients had swelling in the peritonsillar, lateral pharyngeal or retropharyngeal space. Fifteen patients (13%) had intra-oral swelling only. Seventeen patients (15%) had an elevation of body temperature (>37°C).

Antibiotic therapy prescribed

Six different antibiotic regimens were prescribed in the study ( Table 1). Penicillin V (500 mg, every six hours) or amoxicillin (500 mg, every eight hours) was prescribed to 65 patients. A combination of a penicillin with metronidazole (500 mg of penicillin V and 400 mg of metronidazole, every eight hours) was prescribed to 24 patients. Other regimens comprised of erythromycin (250 mg, every six hours) for two patients, metronidazole (400 mg, every eight hours) for nine patients and a combination erythromycin with metronidazole (250 mg of erythromycin and 400 mg of metronidazole, every eight hours) for six patients and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Augmentin®; 375 mg every eight hours) for six patients.

The outcome of treatment

No patient had a deterioration of signs and symptoms at the review appointment. An improvement in signs and symptoms (score = 1) was found in 104 (99%) out of 105 patients who underwent incisional drainage, and mean improvement score in this group was 2.5. In particular, 59 patients (56%) were improved dramatically (score = 3). In one patient, the signs and symptoms were unchanged at the review appointment. The site of the tooth involved did not influence the improvement score; mean improvement score of patients whose site of infection was an incisor or canine in maxilla (n=37), a molar in maxilla (n=43), an incisor or canine in mandible (n=5) and a molar in mandible (n=20) was 2.2, 2.2, 2.6 and 2.6, respectively.

Patients who underwent drainage by opening of the root canal also demonstrated improvement within three days. However, the mean improvement score of the seven patients in this treatment group was 1.4. Although this is less than that seen in the incisional drainage group, the difference was not significant due to the large discrepancy in the number of patients in the two groups.

All antibiotic regimens employed produced a satisfactory outcome (mean score, 2.3-2.6) and there was no significant difference in the improvement score between the regimens (Table 1).

Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility

In all but three patients, a pus specimen was obtained at the first presentation. In three patients who underwent drainage by opening of the root canal, it was not possible to obtain a pus sample at the first presentation but this was subsequently collected at the review appointment.

The most frequent bacterial isolates were strains of Prevotella species, Peptostreptococcus species, streptococci and Fusobacterium species (Table 2). Of the 97 isolates of Prevotella species, 30% were resistant to penicillin. All strains of Eikonella species and Veillonella species were resistant to penicillin. Fusobacterium species, Eikonella species and Veillonella species revealed reduced antimicrobial susceptibility to erythromycin. Although all streptococcal isolates were resistant to metronidazole, all isolates of Prevotella species, Peptostreptococcus species and Fusobacterium species were sensitive to this agent. In this study, penicillin-resistant bacteria were isolated from 42 (38%) of the patients.

Presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in patients already receiving antibiotic therapy

A total of 42 patients had previously been administrated one or more antibiotics by either their general dental or medical practitioner (39 patients) or by the hospital (three patients). The mean duration of the antibiotic therapy prior to collection of the pus sample was 2.1 days (range, 1-10 days). None of the subjects had received any other antibiotic in the six months prior to their present infection.

Thirty-four patients had received a penicillin (penicillin V, amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) and these are referred to in this study as the Penicillin (+) group. Penicillin-resistant bacteria were isolated in 18 patients (53%) in Penicillin (+) group and this prevalence was significantly higher than that in patients who had not received penicillin (Penicillin (−) group) (P=0.034, Table 3). There was no significant correlation between prevalence of penicillin-resistant bacteria and duration of administration or dosage of penicillin (data not shown). Interestingly, strains of penicillin-resistant Prevotella species were isolated more frequently in Penicillin (+) group than in Penicillin (−) group (P=0.013) although there was no significant difference in prevalence of penicillin-resistant bacteria other than Prevotella species between both groups. Prevalence of erythromycin-resistant bacteria had no significant correlation with administration of penicillin. There was also no significant difference in prevalence of erythromycin-resistant bacteria and penicillin-resistant bacteria between patients who had received erythromycin and patients who had not previously received this antibiotic.

Influence of penicillin-resistance on the treatment

A total of 65 patients received penicillin alone (penicillin V or amoxicillin) following surgical drainage. Of the 65 patients, 28 (43%) had penicillin-resistant bacteria in the pus specimen obtained at the first presentation, but all of these patients had improved signs and symptoms at review appointments. The mean improvement score of these patients was 2.5, which was not significantly different to the mean score (2.4) of patients who did not have penicillin-resistant isolates in the pus (Table 4). Similarly, there was no difference in outcome according to the presence or absence of penicillin-resistant bacteria in the 24 patients who received a combination of a penicillin and metronidazole.

Discussion

The first principle of the management of acute dentoalveolar infection involves the establishment of surgical drainage. The second principle is assessment of the patient to determine the need for adjunctive systemic antibiotic therapy. Whilst many studies have reported the types of antibiotic prescribed for acute dental infections, either in general dental practice or hospital out-patient clinics, there would not appear to have been any investigations that have audited the clinical outcome of such treatment. The present study represented an outcome audit that attempted to investigate the potential benefit or indeed lack of impact of antibiotic therapy prescribed in a hospital-based examination and emergency unit. In this audit, the majority (94%) of patients underwent incisional drainage of soft tissue swelling and were provided with a systemic antibiotic at the time of first presentation. A clinical improvement was found in all but one patient within three days. In seven patients it was not possible to establish drainage through the soft tissue. However, these patients, who underwent drainage by opening of the root canal and received systemic antibiotic therapy, also had improved signs and symptoms at review. Interestingly, the degree of improvement was less than that recorded in those patients who underwent incisional drainage. This observation would support the generally accepted belief that incisional drainage of the soft tissues is preferable to drainage through the root canal. In each case, an attempt should be made to establish surgical drainage by one of these routes and treatment should not be based on the provision of antibiotic therapy alone.13

Since the incidence of resistance to penicillin in dental infections appears to be increasing in a number of countries worldwide, it has been debated whether antibiotic therapy, if indicated, involving penicillin is appropriate to manage odontogenic infections.4,5 In the present study, the presence of penicillin-resistant bacteria within the abscesses did not affect the outcome of treatment with penicillin. Moreover, this study revealed no significant difference in clinical outcome with any of the antibiotic regimens prescribed. These findings raise important questions in relation to the role of antibiotics. It could be argued that if it is felt that an antibiotic is required then any of the regimens prescribed here could be used. Penicillins appear to be effective despite the presence of penicillin-resistant bacteria, provided that surgical drainage has been established. Therefore, members of the penicillin group should be still considered as a suitable antibiotic for acute dental infections in cases where antibiotic therapy is considered necessary. However, this audit did not address the question related to the actual need for any form of antibiotic if adequate drainage has been achieved. All the patients included in the audit were cases where the individual clinician involved in the management of the patient had decided that antibiotic therapy was required. It is not ethical to withhold antibiotic therapy from a patient where the symptoms indicate the need for its use. However, the findings reported here certainly strongly suggest that antibiotic therapy was probably not required in all the cases included in the audit. Since this was an outcome audit, a control group of patients who were treated by drainage alone was not appropriate as explained above. However, it would be interesting to conduct a similar audit recording the outcome of a group of patients who are treated with drainage alone.

It is sometimes not possible to establish any form of drainage due to diffuse cellulitis or the presence of a post-crown on the abscessed tooth. In these circumstances, antibiotic therapy may have a more important role,2 and presence of penicillin-resistance could affect the outcome of treatment. The present study did not determine the effect of tooth extraction because patients who underwent tooth extraction at the first presentation were not included. Further studies are required to address these questions.

Prevotella species, Peptostreptococcus species, streptococci and Fusobacterium species were the predominant isolates from the patients studied here. This finding is consistent with other microbiological studies of dental infections.6,7,14,15,16,17 Interestingly, Porphyromonas species was rarely encountered and Eikonella species and Veillonella species were isolated more frequently compared to previous studies.6,7,14,15,16,17 These variations could in part be due to differences in culture media used for the initial isolation. Almost all isolates of streptococci, Peptostreptococcus species and Fusobacterium species were susceptible to penicillin. However, 30% of Prevotella isolates were resistant to penicillin. Moreover, all isolates of Eikonella species and Veillonella species were resistant to penicillin. Although resistance to penicillin in Prevotella species has previously been reported,1,2,34,5 Eikonella species and Veillonella species have been reported to be susceptible to penicillin.11 Further study is necessary to confirm an apparent increase in antibiotic resistance in these bacteria.

In this audit, penicillin-resistant bacteria were recovered from 42 (38%) of the patients. It has been reported that the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria correlates with previous administration of antibiotics in dental infections6,9,10 although some studies do not support this conclusion.8,18 In the present study, there was no significant correlation between prevalence of erythromycin-resistant bacteria and previous administration of erythromycin. However, penicillin-resistant bacteria were isolated significantly more frequently from patients previously given penicillin (p<0.05). Interestingly, patients with a history of penicillin therapy had a significantly higher incidence of penicillin-resistant Prevotella species (p<0.02) when compared with the Penicillin (−) group. This was not however the case for other bacterial species isolated (mainly Eikonella species and Veillonella species). These findings support the proposal that administration of penicillin could influence the abscess microflora and promote the emergence of penicillin-resistant Prevotella species. Penicillin-resistance in Prevotella species is usually due to production of β-lactamase, an enzyme capable of penicillin degradation.14,19 An experimental study has demonstrated that β-lactamase produced by Prevotella can protect not only the Prevotella species themselves but also the other bacteria in the mixed infections from penicillin therapy.19 In the situation where an infection has not improved despite the administration of systemic penicillin, the presence of penicillin-resistant Prevotella species should be suspected and antimicrobial therapy changed to one that is stable to β-lactamase, such as metronidazole, erythromycin or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.

In conclusion, this would appear to be the first reported outcome audit of the treatment of acute dental infections. The results have confirmed previous reports of a relatively high incidence of penicillin-resistance in dental infections. However, the clinical observations also indicate that the presence of penicillin-resistant strains in the mixed microflora of a dental abscess does not appear to adversely affect the outcome of treatment when penicillin is prescribed as an adjunct to surgical drainage. This finding has interesting implications and may indicate that the provision of systemic penicillin, or indeed any of the other antibiotics prescribed, in many of the cases studied here was not required. Further outcome audits, possibly based in general dental practice and involving patients who are managed by surgical drainage alone, are required to provide further evidence that may be used to limit the prescribing of antibiotic therapy for acute dental infections.

References

Heimdahl A, Nord CE . Treatment of orofacial infections of odontogenic origin. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 1985; 46: 101– 105.

Peterson LJ . Principles of management and presentation of odontogenic infections. In Peterson LJ (ed) Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery. 3rd ed. pp 392– 417. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

Dahlén G . Microbiology and treatment of dental abscesses and periodontal-endodontic lesions. Periodontol 2000 2002; 28: 206– 239.

Sandor GK, Low DE, Judd PL, Davidson RJ . Antimicrobial treatment options in the management of odontogenic infections. J Can Dent Assoc 1998; 64: 508– 514.

Heimdahl A, von Konow L, Nord CE . Isolation of β-lactamase-producing Bacteroides strains associated with clinical failures with penicillin treatment of human orofacial infections. Arch Oral Biol 1980; 25: 689– 692.

Kuriyama T, Nakagawa K, Karasawa T, Saiki Y, Yamamoto E, Nakamura S . Past administration of ?-lactam antibiotics and increase in the emergence of β-lactamase-producing bacteria in patients with orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 89: 186– 192.

Lewis MAO, MacFarlane TW, McGowan DA . Antibiotic susceptibilities of bacteria isolated from acute dentoalveolar abscesses. J Antimicrob Chemother 1989; 23: 69– 77.

Heimdahl A, von Konow L, Nord CE . β-lactamase-producing Bacteroides species in the oral cavity in relation to penicillin therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 1981; 8: 225– 229.

Kinder SA, Holt SC, Korman KS . Penicillin resistance in the subgingival microbiota associated with adult periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol 1986; 23: 1127– 1133.

Murray PR, Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken RH . Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1999.

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard M2-A7. Villanova: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, 2000.

Dailey YM, Martin MV . Are antibiotics being used appropriately for emergency dental treatment? Br Dent J 2001; 13: 391– 393.

Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto E, Nakamura S . Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive cocci isolated from pus specimens of orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2002; 17: 132– 135.

Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto E, Nakamura S . Incidence of β-lactamase production and antimicrobial susceptibility of anaerobic gram-negative rods isolated from pus specimens of orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2001; 16: 10– 15.

Brook I, Frazier EH, Gher ME . Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of periapical abscess. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1991; 6: 123– 125.

von Konow L, Kondell PA, Nord CE, Heimdahl A . Clindamycin versus phenoxymethylpenicillin in the treatment of acute orofacial infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1992; 11: 1129– 1135.

Fleming P, Feigal RJ, Kaplan EL, Liljemark WF, Little JW . The development of penicillin-resistant oral streptococci after repeated penicillin prophylaxis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990; 70: 440– 444.

Hackman AS, Wilkins TD . Influence of penicillinase production by strains of Bacteroides melaninogenicus and Bacteroides oralis on penicillin therapy of an experimental mixed anaerobic infection in mice. Arch Oral Biol 1976; 21: 385– 389.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs Pat Bishop and Mrs Gillian Fellows at the Oral Microbiology Laboratory, University Dental Hospital, Cardiff for processing the microbiological samples. The authors are also grateful to the patients and clinical staff who contributed to this study. They also acknowledge Professor Tadahiro Karasawa (School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan) for his helpful suggestions for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuriyama, T., Absi, E., Williams, D. et al. An outcome audit of the treatment of acute dentoalveolar infection: impact of penicillin resistance. Br Dent J 198, 759–763 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812415

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812415

This article is cited by

-

International questionnaire study on systemic antibiotics in endodontics. Part 1. Prescribing practices for endodontic diagnoses and clinical scenarios

Clinical Oral Investigations (2022)

-

Comparison of antimicrobial prescribing for dental and oral infections in England and Scotland with Norway and Sweden and their relative contribution to national consumption 2010–2016

BMC Oral Health (2020)

-

Pharmacoeconomic analysis of antibiotic therapy in maxillofacial surgery

BDJ Open (2017)

-

Maxillofacial Infections of Odontogenic Origin: Epidemiological, Microbiological and Therapeutic Factors in an Indian Population

Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery (2016)

-

An outcome audit of three day antimicrobial prescribing for the acute dentoalveolar abscess

British Dental Journal (2011)