Key Points

-

GDPs in Scotland are largely unaware of current child protection guidelines.

-

Inadequate undergraduate and postgraduate training has resulted in significant barriers to referral to the child protection agencies.

-

Future training should address the recognition of the signs of child abuse and knowledge of both the pathways of referral and interagency working.

Abstract

Objectives To identify from general dental practitioners: undergraduate and postgraduate training experience in child protection; numbers of suspected cases of child physical abuse; reasons for failing to report suspicious cases of child physical abuse; knowledge of local child protection protocols and procedures for referral.

Materials and methods Postal questionnaires were sent to 500 randomly selected general dental practitioners in Scotland, with a further 200 sent to a random sample of the original 500 to increase response rate.

Results Sixty-one per cent (306) of the original 500 questionnaires, and 35% (69) of the second random mail shot of 200 questionnaires were returned. Only 19% could remember any undergraduate training and 16% had been to a postgraduate lecture or seminar in child protection. Twenty-nine per cent of dentists had seen at least one suspicious case in their career. Only 8% of suspicious cases were referred on to the appropriate authorities. Reasons for failure to refer revealed that 11% were concerned about a negative impact on their practice, 34% feared family violence towards the child, 31% feared violence directed against them, and 48% feared litigation. Only 10% of dentists had been sent a copy of the local child protection guidelines on commencing work and only 15% had seen their Area Child Protection Committee (ACPC) Guidelines via any route.

Conclusions Due to lack of training or clear guidelines for dentists in Scotland, most practitioners were unsure what to do in the event of a suspicion of child abuse. Twenty-one per cent of dentists had encountered suspicious cases but failed to take any action. Dentists overwhelmingly requested appropriate training. This training should address dental competence in assessment of suspicious indicators and involve dentists in inter-agency child protection training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current UK Government and Scottish Executive legislation aims to reduce the incidence of child abuse with measures such as the Sex Offenders' Register1 and the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act, 2003.2 The latter has made it illegal to hit a child on or around the head, shake them or strike them with implements. While most children are very safe at home, it is unfortunate that the home can be the setting for most cases of child abuse.

Many of the signs of physical abuse manifest in the oro-facial region and dental practitioners have extensive knowledge and access to this area. Although dentists as healthcare professionals are ideally positioned to intercept physical abuse3 there is still a reluctance to do so.4,5 The need for our research was made clear following the Laming Report into the death of Victoria Climbié.6

This study sought to identify from a cohort of general dental practitioners in Scotland: undergraduate and postgraduate training experience; the number of suspected cases of child physical abuse; the reasons for failing to report suspicious cases; knowledge of local child protection protocols; and procedures for referral.

Methods and materials

Development of the questionnaire

A questionnaire was designed to investigate: specific areas of knowledge; demographics; education; suspicion; action and reasons for non-action; local procedures and personnel; perceived responsibility; and personal involvement.

Information regarding the number of general dental practitioners in Scotland can be obtained from the Information and Statistics Division (ISD) Scotland website. This site also contains important information regarding the numbers of practitioners in each health board area. However the numbers provided are overestimated because if a dentist owns more that one practice or works in two different health board areas they will be registered twice. On the year ending March 2003 there were 1,891 principal dentists in Scotland. We were able to ascertain how many worked in each of the 15 health board areas and what percentage of the population this covered. Access to a complete list of practitioners was denied due to the Data Protection Act. A list was therefore laboriously compiled from public records (Yellow Pages — yell.com).

Questionnaires were sent to approximately a quarter of randomly selected general dental practitioners in Scotland. A representative number were sent to each of the 15 health boards in Scotland. The questionnaires were posted in March 2003, along with a covering letter and a stamped, addressed return envelope. In August 2003 a repeat questionnaire was sent out to a random sample of the original cohort with a further covering letter and stamped, addressed return envelope. In this second 'mail-shot' 200 of the initial 500 were re-mailed in order to boost replies. This time the covering letter asked the dentist to pass the questionnaire on to one of their colleagues for completion if they themselves had already completed the survey. Due to the random nature of the initial mailing individual dentists could not be identified, therefore it was impossible to only mail the dentists who had not replied.

Statistical analysis

Results used to describe these studies were mainly observational statistics, but where comparisons and significant differences were explored then chi square analysis was completed and p-values generated.

Results

Three hundred and seventy-five questionnaires were returned; a response rate of 75%.

Demographics

In most instances the returns which we received were representative of the health board in question. 8.8% of the responders were under the age of 30; 32.9% were between 30 and 39; 36.1% were aged 40 to 49; and the over 50s made up the remaining 22.2%. The age and gender distribution of respondents is shown in Table 1. Sixteen per cent of respondents had been qualified for less than 10 years; 40% had been qualified between 10 and 19 years; 31% had been qualified between 20 and 29 years; and 14% had been qualified for more than 30 years.

Training

Only 19% of respondents could recall child abuse/protection as part of their formal undergraduate dental lecture or seminar programme. Significantly more females could remember having undergraduate training than males (p<0.001). Those most recently qualified were more likely to remember educational input on this subject (p<0.001). Only 16% of respondents reported that they had received postgraduate training. For 85% the training was in the form of a single lecture/seminar.

Practice

Twenty-nine per cent of respondents had suspected child abuse in one or more of their patients during their career. Only 8% had reported their concerns. A significant number of those who suspected abuse had been involved in postgraduate training (p<0.001). In the preceding five years 39 dentists had seen one suspected case, 17 dentists two cases, five dentists three cases, one dentist four cases, one dentist five cases and two dentists 10 cases each. Five respondents reported that they had seen a suspicious case in the preceding six months. For those that had suspected abuse only 56% had recorded their observations in the clinical notes.

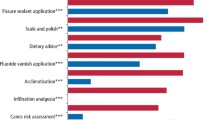

Given a hypothetical suspicious case, in the absence of clear guidelines 24% of respondents would refer/discuss with social services, 12% would seek help from the police, 4% would call Children First and 26% would talk to a paediatric colleague. Nineteen per cent of those who answered would approach more than one of the listed people/agencies, and 15% would contact someone not mentioned on the list. The latter categories included: the patient's general medical practitioner; health visitors; teachers; friends involved in any of the appropriate agencies; and spouses.

Factors influencing practice

Eleven per cent were concerned that a referral may impact on their practice (financial, time taken, loss of income, income withdrawal). Thirty-four per cent feared family violence to the child, 31% feared family violence toward them personally, and 48% were fearful of litigation. The younger respondents (p<0.05) and the female respondents (p<0.01) were more likely to be fearful of these factors. Fear of the consequences to the child from the intervention of statutory agencies would prevent 52% from referring and 71% said that lack of knowledge regarding referral procedures would play a part in their decision whether or not to refer. In 88% of cases a lack of certainty about the diagnosis would affect this decision. Other reasons recorded were: lack of confidence in their suspicions; not wanting to interfere; fear for their own children who may attend the same school in a small community; uncertainty about what action the child protection agencies may take; matters of confidentiality and data protection; and outright denial of abuse by the parent or child.

Ten per cent of respondents had received local guidelines when they commenced work but only a further 5% of respondents had subsequently seen them. Even fewer (2%) knew the identity of the lead clinician for child protection in their area. Only 4% of respondents could recall seeing any inter-agency training courses in child protection advertised in their area.

Child protection procedures

Eighty-one per cent of respondents would prefer to discuss their suspicions with a dental colleague before referring on to the appropriate authorities. Fifty-nine per cent felt that the dental team were well placed to recognise behaviour and/or signs that may be attributable to child abuse and respondents who had suspected abuse during their working life were also the ones more likely to feel that the dental team were well placed to recognise signs of abuse (p<0.05). Ninety-four per cent of respondents thought that general dental practitioners were inadequately informed about issues of child protection and over 78% requested further training on how to recognise and report suspected child abuse. Eighty-seven per cent thought that this training should occur as part of vocational training. Using a scale of 0 to 10, concerning the extent that respondents were willing to get involved in detecting physical abuse, some 20% responded between 0 and 3, 59% between 4 and 6, and 37% between 7 and 10. Only one respondent currently sat on a multi-agency child protection committee.

Twenty-nine per cent of respondents expressed that they would be interested in formulating guidelines for the role of Dental Practitioners in Child Protection. Respondents who had previously suspected abuse were more interested in formulating guidelines than those who had never seen a suspicious case (p<0.001).

Further comments were invited and expressed at the end of the questionnaire. Issues raised were: training and the increased need for it; time restraints already placed on dentists made it difficult to assess for child protection issues; lack of confidence in the statutory agencies.

Discussion

This study is representative of general dental practitioners working in Scotland today.

Demographics

Only 9% of the respondents in this study were under the age of 30. This would seem representative considering that most dentists are at least 23 years old by the time of qualification and the survey did not include vocational trainees. In addition a proportion of young dentists work as junior hospital staff and were not included.

Thirty-three per cent of respondents were between the ages of 30 and 39 while 36% were between the ages of 40 and 49. These figures adequately represent the majority of the workforce in general dental practice. Twenty-two per cent were over the age of 50, representing an increasing number of retirals in this age band.

The study shows a significant difference between the number of male and female dentists. Dentistry was traditionally a male dominated profession and the vast majority of older responders are male. However over the last 10 years there has been a trend towards more female graduates and this could account for the majority of dentists under the age of 30 being female.

Training

Only 19% responded that child abuse/protection formed part of their formal undergraduate dental lecture or seminar programme and this is lower than a comparable study.7 Eighty per cent of respondents could not remember any instruction in child protection with more of the younger dentists recalling training than the older graduates. Only 16% of respondents had attended postgraduate lectures/seminars on child abuse/protection. Previous research has shown5 that although the need to keep up-to-date in child protection was recognised by dentists, time and financial pressures together with low levels of external regulations in this area limited participation in postgraduate training. Courses on child protection, when available, had to compete with more clinical topics. In Scotland section 63 courses have not tended to cover topics such as child protection, and any available interagency courses are rarely advertised in dental circles. There are also constraints on funding and a dentist is less likely to attend a course for which they were not subsidised under the section 63 system and which by definition has not been designated a national priority. While subjects such as the detection of oral cancer may be given high priority, it is disturbing to think that a general dental practitioner may refer one case of oral cancer during their entire practising lifetime but over 29% of our sample of dentists had seen a case of suspected abuse in their career, and one in five dentists within the last five years. Proficiency in detection and awareness in both of these subjects may save a life, yet far more dental public health funding is concentrated on the detection of oral cancer.

Practice

Almost one third of the dentists had suspected abuse on at least one occasion. This is similar to some studies8,9 but is lower than others.10,11 A significant number of those who had suspected abuse had also been involved in postgraduate training (p<0.001) reinforcing the belief that better training increases awareness.

Twenty-one per cent of the respondents admitted that they had suspected abuse but had not reported their concerns. This corresponds with a number of previous studies,7,8,9,10,11,12 where despite a general awareness and suspicion of child abuse there was poor reporting. This may be due, in part, to the lack of legislation for dental practitioners governing the reporting of suspected child abuse in the UK, in comparison to the mandated reporting in the USA.

Recording observations in clinical notes was poor compared to an Australian study.9 Good record keeping is essential in dentistry and defence organisations stress their importance. In possible cases of child abuse the injuries that are seen by dentists should be documented along with any other significant findings, for example the way the child interacts with their caregiver. If photographic evidence of the injuries can be collected this can serve as vital information not only during the healing of injuries but also in any child protection procedures.

It was not surprising that the majority of respondents would prefer to speak with an experienced dental or paediatric colleague rather than refer directly to the police or social services. The dentist may feel more comfortable referring within the realms of a health service of which they have a practical understanding rather than a service that they may know nothing about. Likewise when asked if there was someone not described on the questionnaire to whom they would speak, the majority cited the child's general medical practitioner. Unfortunately general medical practitioners may be subject to exactly the same barriers to referral as dentists.

Factors influencing practice

Many factors were identified that would influence respondents' behaviour if faced with a suspected case of child abuse. As previously reported one such factor was the perceived impact of making a referral on their practice (financial, time taken, loss of income, income withdrawal).3,9

Thirty-four per cent of respondents suggested that fear of family violence to the child would influence a referral which is much lower than previously reported.9 In this earlier study 87% of general dentists said they would consider possible effects on the child before deciding whether or not to refer a case on to the appropriate authorities while 50% would consider possible effects on the child's family. Almost a third of respondents in the current study reported that they would not refer due to fear of family violence toward themselves. This has also been reported previously,5 with dentists anticipating at the very least antagonism from parents, with verbal and physical abuse seen as likely. While it would be highly unpleasant for a dentist to be aggressively attacked it is within their power to take legal action against the perpetrator. The welfare of the child is paramount. Fear and reticence to report is understandable but the dental profession does have a responsibility to the welfare of children.

Forty-eight per cent of dentists stated that fear of litigation may affect referral and many other authors have explored this concern.9,13,14,15,16 However if referral is in good faith, with the interests of the child paramount, then litigation is highly unlikely to be an issue.

Fear of the consequences to the child from the intervention of statutory agencies would prevent 52% from referring. This despite a recent inquiry,6 which highlighted that failure of communication both within and between child protection agencies, resulted in the death of Victoria Climbié at the hands of her caregivers. A previous study has also highlighted concern about the impact on the child and family if they 'got it wrong' and the risk of 'making things worse'.5 Seventy-one per cent and 85% indicated that lack of knowledge or certainty regarding procedures played a part in their decision to refer. This concurs with other studies.9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 In one study5 coping with uncertainty contrasted with routine practice, where dentists were accustomed to feeling confident in identifying signs and symptoms of disease and trauma and taking appropriate actions to deal with them. Poor knowledge of the signs and symptoms, referral routes and potential outcomes contributed to a lack of certainty and made action less likely in suspicions of child abuse. Other potential barriers to reporting included: patient confidentiality and data protection issues; fear of retribution against the dentist's own child where children go to school together in a small community; and just not wanting to become involved in anything other than straightforward dentistry. Confidentiality concerns have been reported elsewhere.9

Only 10% of respondents had received local area child protection guidelines when they first started work at their practice and a further 5% had subsequently seen them. Local child protection guidelines should be available to all healthcare workers yet it would seem that general dental practitioners have slipped through the net. There are no specific guidelines for dentists in Scotland but they are briefly mentioned alongside other health professionals in a few of the available Area Child Protection Guidelines (ACPC), guidelines (currently under review). Some local health authorities produce small booklets for general medical practitioners containing the names of key personnel in health, social services and the police; it would be helpful if such booklets could be produced specifically for general dental practitioners.

Child protection procedures

Fifty-nine per cent of respondents felt that the dental team were well placed to recognise behaviour and/or signs that may be attributable to child abuse. Unsurprisingly the respondents who had seen abuse previously felt well placed to recognise the signs. The high demand for further training suggests that there is a significant gap in current training which should be addressed. Without adequate training dental staff will not feel empowered to take responsibility for referring a child to the protection services. This mismatch between dental practitioners' attitudes to and knowledge of the child protection process and the reality of child abuse poses of itself a significant risk to children.

Conclusions

Due to lack of training or clear guidelines, dentists in Scotland were unsure what to do in the event of a suspicion of child abuse. Twenty-one per cent of dentists had encountered suspicious cases but failed to take any action.

Dentists overwhelmingly requested appropriate training.

Future training should address dental competence in assessment of suspicious indicators and should involve inter-agency training with the other healthcare professionals involved in child protection.

References

The Sex Offenders Act. Sentencing and Offences Unit. London: Home Office, 1997.

Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive, 2003.

Senn DR, McDowell JD, Alder ME . Dentistry's role in the recognition and reporting of domestic violence, abuse and neglect. Dental Clinics of North America 2001; 45: 343– 363.

Jessee SA . Child abuse and neglect: implications for the dental profession. Texas Dent J 1999; 116: 40– 46.

Welbury RR, MacAskill SG, Murphy JM et al. General dental practitioners' perception of their role within child protection: a qualitative study. Euro J Paed Dent 2003; 4: 89– 95.

Department of Health. The Victoria Climbié Inquiry. Report of an inquiry by Lord Laming. London: Stationary Office, 2003.

Ramos-Gomez F, Rothman D, Blain S . Knowledge and attitudes among California dental care providers regarding child abuse and neglect. J Amer Dent Ass 1998; 129: 340– 348.

Kilpatrick NM, Scott J, Robinson S . Child protection: a survey of experience and knowledge within the dental profession of New South Wales, Australia. Int J Paed Dent 1999; 9: 153– 159.

John V, Messer LB, Arora R et al. Child abuse and dentistry: a study of knowledge and attitudes among dentists in Victoria, Australia. Aust Dent J 1999; 44: 259– 267.

Saxe MD, McCourt JW . Child abuse: a survey of ASDC members and a diagnostic-data-assessment for dentists. ASDC J Dent Child 1991; 58: 361– 366.

Von Burg M M, Hibbard RA . Child abuse education: Do not overlook dental professionals. ASDC J Dent Child 1995; 62: 57– 63.

Needleman HL, MacGregor SS, Lynch LM . Effectiveness of a statewide child abuse and neglect educational program for dental professionals. Ped Dent 1995; 17: 41– 45.

Croll TP, Menna VJ, Evans CA . Primary identification of an abused child in a dental office, a case report. Ped Dent 1981; 3: 339– 341.

Case JH, Phillips GP, Zatopek DL . Be aware! Child abuse or neglect? Texas Dent J 1982; 99: 6– 10.

Sanger R G, Bross D C . Clinical management of child abuse and neglect: a guide for the dental profession. p 47. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing, 1984.

Donly KJ . Child abuse and neglect: a dental perspective. Iowa Dent J 1986; 72: 33– 36.

Malecz RE . Child abuse, its relationship to pedodontics: a survey. ASDC J Dent Child 1979; 46: 193– 194.

Kassebaum DK, Dove SB, Cottone JA . Recognition and reporting of child abuse: a survey of dentists. Gen Dent 1991; 39: 159– 162.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cairns, A., Mok, J. & Welbury, R. The dental practitioner and child protection in Scotland. Br Dent J 199, 517–520 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812809

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812809

This article is cited by

-

Child abuse knowledge and attitudes among dental and oral health therapists in Aotearoa New Zealand: a cross-sectional study

BMC Health Services Research (2022)

-

A dentist's dilemma: sharing wellbeing concerns to safeguard Scotland's children

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Child maltreatment in Dubai and the Northern United Arab Emirates: dental hygienists and assistants’ knowledge

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)

-

Child physical abuse: knowledge of dental students in Hamburg, Germany

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)

-

Can child safeguarding training be improved?: findings of a multidisciplinary audit

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2020)