Abstract

Successful advances in the treatment of advanced malignant diseases rely on recruitment of patients into clinical trials of novel agents. However, there is a genuine concern for the welfare of individual patients. The aim of this study was to examine motives of patients entering early clinical trials of novel cancer therapies. Questionnaire survey with both open- and close-ended questions. The patients were surveyed after they had given informed consent and before or during the first cycle of treatment. In all, 38 phase I/II trial patients participated and completed the survey. Obtaining possible health benefit was listed by 89% as being a ‘very important’ factor in their decision to participate, with only 17% giving reasons of helping future cancer patients and treatment. Other items cited as a ‘very important’ motivating factor were ‘trust in the doctor’ (66%), ‘being treated by the latest treatment available’ (66%), ‘better standard of care and closer follow-up’ (61%), and ‘closer monitoring of patients in trials’ (58%). Only 47% patients indicated that someone had explained to them about any ‘reasonable’ alternatives to the trial. In total, 71% strongly agreed that ‘surviving for as long time as possible was the most important thing (for them)’. Nearly all (97%) indicated that they knew the purpose of the trial and had enough time to consider participation in the trial (100%). In this survey, most patients entering phase I and II clinical trials felt they understood the purpose of the research and had given truly informed consent. Despite this, most patients participated in the hope of therapeutic benefit, although this is known to be a rare outcome in this patient subset. Trialists should be aware, and take account of the expectations that participants place in trial drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Successful advances in the treatment of advanced malignant diseases are reliant on recruitment of patients into clinical trials of novel agents (Tannock, 1995). These studies are normally restricted to patients with advanced malignant disease that is refractory to standard therapy. There is, however, genuine concern with regard to the welfare of the individual patients in such clinical trials (The National Commission, 1979; Faden et al, 1986).

Although all phases of clinical trials are associated with ethical issues, there are particular problems with phase I and phase II trials. Firstly, preclinical experiments provide only limited information from which to predict the dose, schedule, toxicity, and anticancer activity of the drug in man. Patients in phase I trials, therefore, run the risk of receiving doses of drug that have no biological effect or, alternatively, excessively high doses with the risk of serious toxicity. Although phase I trials of newer agents have the potential to minimise the risk of toxicity by using more rational biological end points, most current trials still use the traditional end points of toxicity for selection of the recommended phase II dose (Parulekar and Eisenhauer, 2004). Similar risk can also occur in phase II trials. Secondly, this is a particularly vulnerable group of patients, who are usually well aware of their advanced malignant disease, short life expectancy, and lack of established treatment options. Ethically, treatment of these patients should ensure that they are well informed about potential risks and benefits associated with trial participation as well as the alternatives to trial participation.

Patients' understanding of the difference between therapeutic and nontherapeutic research has been called into question (Appelbaum et al, 1987; Lidz et al, 2004). The published literature on patient motivation to participate in clinical trials suggests that altruism may not be the sole motivating factor; self-interest is also important (Penman et al, 1984; Rodenhuis et al, 1984; Kodish et al, 1992; Daugherty et al, 1995; Itoh et al, 1997; Yoder et al, 1997). A recent systematic review, however, has questioned whether participation in clinical trials is of any benefit to participants (Peppercorn et al, 2004). Various studies have reported that the chance of therapeutic response for those volunteering to take part in phase I trial is less than 5% (Estey et al, 1986; Decoster et al, 1990; Von Hoff and Turner, 1991; Smith et al, 1996; Roberts et al, 2004). In phase II clinical trials, the overall objective response rate (partial and complete) is also usually low. Higher response rates (>20–30%) must be observed in breast or small cell lung cancer to make a new drug interesting for further development, as there are numerous drugs already active in these tumour types. In contrast, in tumour types such as glioma and melanoma where there are few effective treatments response rates as low as 5% may still render the drug interesting and potentially useful as a future treatment option.

In this study, we investigated the motivations and inhibiting factors for patients participating in phase I and phase II cancer clinical trials, their understanding of the purpose of the research and alternatives to trial participation, and influences on the decision to enter the trial.

Materials and methods

Between January 2001 and January 2002, patients with advanced or metastatic cancer attending the Aberdeen and North Centre for Haematology, Oncology and Radiotherapy (ANCHOR) Unit who had given informed consent to participate in clinical trials were invited to take part in a questionnaire study. The local ethical committee approved the study design and the final format of the questionnaire. Patients were identified through the hospital's Medicines Assessment Research Unit (MARU) and the oncology research nurses. The patients were approached as in-patients or outpatients, depending on the nature of the treatment they were receiving.

The survey's principal investigator (PI) asked patients if they would agree to participate in a questionnaire survey that would take around 15–20 min to complete (see Supplementary information). Once verbal approval was obtained, the PI issued the questionnaire before any treatment began. Assurance was given to patients that it would not affect their treatment should they choose not to complete the questionnaire, and that their anonymity would be maintained. The questionnaire was completed in the absence of the research nurses. The questionnaires were returned by mail (stamped addressed envelope was provided where necessary) or hand delivered to the ward or the clinic. A maximum of 1 month was allowed for the return of the questionnaire.

Study instruments

The questionnaire was adopted from Daugherty et al (1995) with the author's permission, but included a new section on the ‘trade-off’ between quality of life (QOL) and long-term survival. Prior to commencing this study, the questionnaire was piloted with 20 patients at a similar stage of recruitment to cancer trials to ensure clarity of meaning.

Analysis of the data was carried out using SPSS for Windows (version 10.0.7 program). The primary statistical analysis was intended to be descriptive in nature. Secondary analysis was performed using nonparametric tests for independent samples with the Mann–Whitney test for two-sided independent samples at the 5% significance level. Accuracy of the data was checked in 100% of the cases by the second author after going through each questionnaire and checking all the completed data input.

Results

Patient accrual

In all, 104 patients were approached for the study. Of these, 63 patients were participants of phase III trials and were ineligible for the study. Of the remaining 41 patients, 14 were participants in phase II trials and 27 in phase I trials. We found that we had double counted two patients who had completed the questionnaire twice (for different trials), so we excluded their second questionnaires, and another that was largely incomplete, leaving a final cohort of 38 participants. Tables 1 and 2 show the demographic and general health characteristics of the participants.

Questionnaire responses

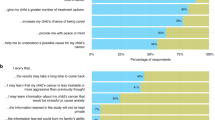

Overall 98% of the close-ended questions were answered. In all, 92% had answered the open-ended question ‘Can you tell us the main reason that you are participating in this clinical trial?’, and these responses were analysed for key words or phrases (hope of remission, help me/help others, improve health, reduce tumour) to look for clues for patient motivation. Only six (17%) gave altruistic reasons of helping future cancer patients and treatment (‘If it can help other cancer patients, then that's good’), whereas 22 (58%) gave answers indicating some hope of therapeutic response (‘To help me get better’, ‘Had two different chemotherapies before but didn't have the desired effect’).

In the closed questions, 30 (82%) listed helping future cancer patients as being a ‘very important’ motivating factor for participating in the trial. Other important motivating items cited were ‘possible health benefit’ (89%), ‘trust in the doctor’ (66%), ‘trust in nurses’ (76%), ‘being treated by the latest treatment available’ (66%), ‘better standard of care and closer follow-up’ (61%), ‘being likely to obtain more information about my condition’ (58%), and ‘closer monitoring of patients in trials’ (58%).

Patient expectations

In total, 35 (92%) thought patients benefit from clinical trials and 33 (87%) rated highly the possibility of personal clinical benefit. If offered the chance to participate in a future trial, 18 (47%) indicated ‘probably yes’ and 16 (42%) ‘definitely yes’. Chemotherapy-naïve patients were more likely to have positive expectations of benefit from participating in the trial than those patients who had previously had chemotherapy (100 vs 78%) (z=1.91; P=0.05). Men were significantly more likely than women (100 vs 64%) to have positive expectations from participating in the trials (z=3.09; P<0.01).

QOL vs long-term survival

In the questions about QOL and length of survival, 27 (71%) strongly agreed that ‘surviving for as long time as possible is the most important thing’ (for them). In all, 21 (55%) strongly disagreed that maintaining QOL was less important. A total of 23 (60%) strongly agreed that they ‘would rather maintain a better QOL for a shorter term than suffer somewhat for longer’, with nine (24%) neither agreeing nor disagreeing (Table 3).

Sources of information

Table 4 shows the sources of information that the patients had used since diagnosis. In all, 29 (76%) sought more information about their illness and treatment options after their diagnosis, 17 (45%) prior to the treatment and 19 (50%) during treatment. A total of 12 (32%) obtained more information when looking for a different treatment. In total, 20 (53%) had contacted relatives, friends, and other people for more information, while the Internet and the MacMillan or Marie Curie organisations were used by 26%. In all, 30 (82%) had discussed their prognosis with their oncologist and 33 (87%) said they understood their prognosis.

Comprehension

When asked through close-ended questions, 37(97%) indicated that they gave informed consent, with 36 (95%) having understood all or most of the trial information given to them (Table 5). Virtually all patients said that someone had explained that the trial was part of medical research, and told them the type of treatment they would be getting. Patients felt they had had plenty of time to think things over. Nearly all patients (97%) said that the side effects they might experience and the risks involved (89%) were explained to them. A total of 18 (47%) patients indicated that someone had explained to them about any ‘reasonable’ alternatives.

Phase I trial patients were significantly more likely than patients on phase II trials (65 vs 25%) to indicate that no ‘reasonable’ alternatives to having this treatment were explained (z=2.287; P<0.05). Patients who previously had chemotherapy were significantly more likely than chemotherapy-naïve patients (70 vs 27%) to indicate that no reasonable alternatives to treatment were explained to them (z=2.554; P<0.01).

Influences

Most (97%) when asked through close-ended questions made up their own mind to participate in the trial, although doctors at the cancer centre, family, and family doctors (to a lesser extent) were also influential (Table 6). In all, 20 (52%) found the decision to participate in the trial ‘easy’. In total, 31 (82%) made the decision to participate completely on their own and seven (18%) partially.

Discussion

We found that most participants felt they were well informed and that their decisions about trial participation were made independently. The main area of concern was that only half of the patients felt that they had ‘reasonable’ alternatives to trial participation explained. Those not aware of ‘reasonable’ alternative treatment were, however, predominantly participants in phase I trials, where the only alternative was likely to have been an alternative experimental therapy or best supportive care.

Our study has some limitations – in particular, it is a small study from a single institution – but the participants are likely to be broadly representative of those in phase I and II clinical trials. On direct questioning, the two main motivational factors for trial participation were possible health benefit and helping future cancer patients. The differences we found in responses to open- and close-ended questions suggest, however, that participants' main motivation was personal health gain. Whereas phrasing of a closed question might influence the response, open-ended question may more freely elicit patients' true feelings. For example, Cox (2003) found that QOL of patients in phase I and phase II cancer drug trials as measured by closed question instruments was unaffected by trial participation, whereas qualitative data from in-depth interviews demonstrated considerable physical and psychological impact from experimental chemotherapy. Our finding that personal health benefit was the most important motivation and expectation for most patients is in line with previous findings (Daugherty et al, 1995; Yoder et al, 1997; Cheng et al, 2000). How then do we explain this apparent mismatch in a group of patients who report being well informed?

Patients may have interpreted the information they received optimistically. Cox (2002) reported that patients interpreted the wording of information sheets optimistically, for example, the words ‘study’, ‘new’, or ‘American’ treatment were taken to mean ‘better’ than conventional treatments. The positive presentation of trials was reinforced by faith patients place in the decision of their consultants to offer this treatment. Our results with regard to trust in doctors are similar to those obtained by Penman et al (1984) and Daugherty et al (1995). This vulnerable group of patients may be at risk of pressure by their doctors to enter studies, but we found few who did not decide independently to participate. Albrecht et al (1999) found that patients were more likely to consent to the trial when their physician verbally presented items normally included in an informed consent document and when they behaved in a ‘reflective, patient-centred, supportive, and responsive manner’.

Cheng et al (2000) found that participants in phase I clinical have high expectations regarding the success of experimental therapy and discount potential toxicity, and that patients perceive potential benefits and toxicities differently than health-care professionals. We observed similar findings in that most patients rated highly the possibility of personal benefit. Slevin et al (1990) found that patients with cancer are willing to accept treatment with cytotoxics for lower chances of benefit than those thought acceptable by their physicians or nurses.

Many patients maintain hope and optimism despite advanced cancer. In a qualitative study, we found that many patients needed to maintain some degree of hope (Bain et al, 2002) and others have reported the same (Leydon et al, 2000). For a patient whose illness has progressed on standard therapy and for whom no other established therapy is available, a less than 5% chance of therapeutic benefit could be regarded as reasonable justification for study entry. Furthermore, with increased use of targeted therapy, the risk of toxic effects experienced by participants in phase I trials is improving (Roberts et al, 2004).

Patients are attracted to a clinical trial by ‘being treated by a doctor with a specialist interest in the disease and encouraged by the possibility that their progress will be monitored closely’ (Slevin et al, 1995). High-quality care and closer monitoring are realistic expectations for phase I and phase II trials. Patients in these trials have a dedicated team of nurses, pharmacists, and doctors looking after them and have close contact with the oncology department. This provides continuity of care, prompt attention to symptom control, and a high level of support.

Our findings confirm that when patients believe they are well informed, their understanding of potential risks (predominantly to QOL) and benefits (mostly in terms of the small potential for benefit to survival) are key to their decisions to participate in phase I and phase II clinical trials. In an attempt to illuminate this further, we asked questions on the trade offs they would make between survival and QOL. Their responses demonstrate the importance they placed on both survival and QOL, but their trade offs were inconsistent with each other (most strongly agreed that survival for as long as possible was most important, and also that QOL was more important than survival). Instead, their responses appear to be in line with the way statements were framed, suggesting that patients' consideration of risks and benefits, even when fully understood, is vulnerable to manipulation (Thornton, 2003).

Overall, we have found that nearly all patients recruited to phase I and II clinical trials felt they were fully informed about the research and, with the possible exception of alternative treatments, appeared to be well informed on direct questioning. Despite this, most took part primarily in the hope of therapeutic benefit. Trialist clinicians should take account of patients' potential misconceptions about early clinical trials of anticancer agents during recruitment, and should ensure clarity and an honest approach to such vulnerable patients.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Albrecht TL, Blanchard C, Ruckdeschel JC, Coovert M, Strongbow R (1999) Strategic Physician Communication and Oncology Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol 17: 3324–3332

Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz CW, Benson P, Winslade W (1987) False hopes and best data: consent to research and the therapeutic misconception. Hastings Cent Rep 17: 20–24

Bain NSC, Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Cassidy J (2002) Striking the right balance in colorectal cancer care – a qualitative study of rural and urban patients. Fam Pract 19: 369–374

Cheng JD, Hitt J, Koczwara B, Shulman KA, Burnett CB, Gaskin DJ, Rowland JH, Meropol NJ (2000) Impact of quality of life on patient expectations regarding phase I clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 18: 421–428

Cox K (2002) Informed consent and decision making: patients' experiences of the process of recruitment to phase I and phase II anti-cancer trials. Patient Educ Couns 46: 31–38

Cox K (2003) Assessing the quality of life of patients in phase I and II anti-cancer drug trials: interviews versus questionnaires. Soc Sci Med 56: 921–934

Daugherty C, Ratain MJ, Grochowski E, Stocking C, Kodish E, Mick R, Siegler M (1995) Perceptions of cancer patients and their physicians involved in phase I trials. J Clin Oncol 13: 1062–1072

Decoster G, Stein G, Holdener EE (1990) Responses and toxic deaths in phase I clinical trials. Ann Oncol 2: 175–181

Estey E, Hoth D, Simon R, Marsoni S, Leyland-Jones B, Wittes R (1986) Therapeutic responses in phase I trials of antineoplastic agents. Cancer Treat Rep 70: 1105–1115

Faden RR, Beauchamp TL, King NMP (1986) A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press

Itoh K, Sasaki Y, Fuji H, Ohtsu T, Wakita H, Igarashi T, Abe K (1997) Patients in phase I trials of anti-cancer in Japan: motivation, comprehension and expectations. Br J Cancer 76: 107–113

Kodish E, Stocking C, Ratain MJ, Kohrman A, Siegler M (1992) Ethical issues in phase I oncology research: a comparison of investigators and institutional review board chairpersons. J Clin Oncol 10: 1810–1816

Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moyniham C, Jones A, Mossman J, Boudini M, McPherson K (2000) Cancer patients' information needs and information seeking behaviour. In depth interview study. BMJ 320: 909–913

Lidz CW, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Renaud M (2004) Therapeutic misconception and the appreciation of risks in clinical trials. Soc Sci Med 58: 1689–1697

Parulekar WR, Eisenhauer EA (2004) Phase I trial design for solid tumour studies of targeted, non-cytotoxic agents: theory and practice. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 990–997

Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, Marrow G, Schmale AH, Ddeog LR, Carnrike CL, Cherry R (1984) Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: patients' and physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol 2: 849–855

Peppercorn JM, Weeks JC, Cook EF, Joffe S (2004) Comparison of outcomes in cancer patients treated within and outside clinical trials: conceptual framework and structured review. Lancet 363: 263–270

Roberts TG, Goulart BH, Squitieri L, Stallings SC, Halpern EF, Chabner BA, Gazelle GC, Finkelstien SN, Clark JW (2004) Trends in the risks and benefits to patients with cancer participating in phase I clinical trials. JAMA 292: 2130–2140

Rodenhuis S, Van Den Heuvel WJA, Annyas AA, Koops HS, Sleijfer DT, Mulder NH (1984) Patient motivation and informed consent in phase I study of an anticancer agent. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 20: 457–462

Slevin ML, Stubbs L, Plant HJ, Wilson P, Gregory WM, Armes PJ, Downer SM (1990) Attitudes to chemotherapy: comparing views of patients with cancer with those of the doctors, nurses, and general public. BMJ 300: 1458–1460

Slevin M, Mossman J, Bowling A, Leornard R, Steward W, Harper P, Mcmurray M, Thatcher N (1995) Volunteers or victims: patients' views of randomised cancer clinical trials. Br J Cancer 71: 1270–1274

Smith TL, Lee JJ, Kantarjian HM, Legha SS, Raber MN (1996) Design and results of phase I cancer clinical trials: 3 year experience at MD Anderson Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol 14: 287–295

Tannock IF (1995) The recruitment of patients into clinical trials. Br J Cancer 71: 1134–1135

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research (1979) The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office

Thornton H (2003) Patients' understanding of risk. BMJ 327: 693–694

Von Hoff DD, Turner J (1991) Response rates, duration of response, and dose response effect in phase I studies of antineoplastics. Invest New Drugs 9: 115–122

Yoder LH, O'Rourke TJ, Ethyre A, Spears DT (1997) Expectations and experiences of patients with cancer participating in phase I clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum 24: 891–896

Acknowledgements

We thank research nurses Martyn Main, Pauline Killham, Margaret Mathieson, and Muriel Reid for their help with the recruiting of patients for the study. Merill Egorin at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute for help in the study's initial phase of development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Nurgat, Z., Craig, W., Campbell, N. et al. Patient motivations surrounding participation in phase I and phase II clinical trials of cancer chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 92, 1001–1005 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602423

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602423

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The Importance of Social Engagement in the Development of an HIV Cure: A Systematic Review of Stakeholder Perspectives

AIDS and Behavior (2023)

-

Why not? Motivations for entering a volunteer register for clinical trials during the COVID-19 pandemic

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2022)

-

Translation and validation of the greek version of a questionnaire measuring patient views on participation in clinical trials

BMC Health Services Research (2021)

-

Patient perceptions of the challenges of recruitment to a renal randomised trial registry: a pilot questionnaire-based study

Trials (2021)

-

“You would not be in a hurry to go back home”: patients’ willingness to participate in HIV/AIDS clinical trials at a clinical and research facility in Kampala, Uganda

BMC Medical Ethics (2020)