Abstract

Mutations in two genes encoding cell cycle regulatory proteins have been shown to cause familial cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM). About 20% of melanoma-prone families bear a point mutation in the CDKN2A locus at 9p21, which encodes two unrelated proteins, p16INK4a and p14ARF. Rare mutations in CDK4 have also been linked to the disease. Although the CDKN2A gene has been shown to be the major melanoma predisposing gene, there remains a significant proportion of melanoma kindreds linked to 9p21 in which germline mutations of CDKN2A have not been identified through direct exon sequencing. The purpose of this study was to assess the contribution of large rearrangements in CDKN2A to the disease in melanoma-prone families using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. We examined 214 patients from independent pedigrees with at least two CMM cases. All had been tested for CDKN2A and CDK4 point mutation, and 47 were found positive. Among the remaining 167 negative patients, one carried a novel genomic deletion of CDKN2A exon 2. Overall, genomic deletions represented 2.1% of total mutations in this series (1 of 48), confirming that they explain a very small proportion of CMM susceptibility. In addition, we excluded a new gene on 9p21, KLHL9, as being a major CMM gene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) (MIM no. 600160) has been increasing rapidly in the Caucasian population in recent decades. Melanoma is a complex and heterogeneous disease with genetic and environmental factors contributing to its development. Population-based studies in Utah and Sweden have reported approximately 2- and 3-fold increased risk of melanoma, respectively, in first-degree relatives of melanoma probands (Goldgar et al, 1994; Hemminki et al, 2003). Indeed, about 10% of CMM cases occur in a familial setting. Familial melanoma is usually defined as a cluster of two or more first-degree relatives with melanoma. Two high-risk genes have been identified: the cell cycle regulator CDKN2A on chromosomal band 9p21 (Hussussian et al, 1994) and the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 (CDK4) on chromosomal band 12p14 (Zuo et al, 1996), the products of which are known to be components of potent tumour-suppression pathway. The CDKN2A gene is the major high-risk CMM susceptibility gene identified to date, as germline mutations in this gene have been found in about 20–40% of melanoma-prone families worldwide (Hayward, 2003). It encodes two distinct proteins, translated in alternate reading frames, from alternatively spliced transcripts. The α transcript encodes the p16 inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase type 4 protein (p16INK4a); the smaller β transcript specifies the alternative product p14ARF. Both of these proteins are involved in cell cycle regulation. Only two germline mutations in CDK4 (MIM no. 123829) have been reported worldwide in a total of six CDKN2A mutation-negative familial melanoma kindreds, and all mutations occur at the arginine encoded by codon 24 in exon 2 of the gene. This arginine directly interacts with p16, and mutations affecting this codon have the same functional effect as a p16 mutation (Zuo et al, 1996; Soufir et al, 1998; Molven et al, 2005).

Although approximately 50% of melanoma-prone families display linkage to 9p21, only about half of these have been identified as carriers of a mutation in the CDKN2A gene (Hussussian et al, 1994; Kamb et al, 1994; Harland et al, 1997; Borg et al, 2000; Laud et al, 2006). These studies suggest, besides the involvement of CDKN2A in susceptibility to melanoma, the possibility of the existence of additional tumour suppressor loci on chromosome 9p21. At the somatic level, the very low frequency of disease-causing alterations (by mutation or inactivation by loss of expression) of the CDKN2A gene in sporadic CMM cases with allelic losses of 9p21 is again consistent with the presence of additional tumour suppressor gene(s) within this chromosomal area (Gonzalgo et al, 1997; Ruiz et al, 1998; Wagner et al, 1998). CDKN2B, located about 30 kb centromeric from CDKN2A and coding the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p15INK4b, was the first obvious candidate gene but has been excluded as being a high penetrance susceptibility gene for CMM (Platz et al, 1997; Laud et al, 2006). The question of whether or not large genomic deletions, undetectable by traditional PCR-amplification and sequencing of individual exons, may be the cause of such unexplained familial clustering of melanoma has been raised, and few authors have searched for large CDKN2A/ARF deletions or rearrangements (Fitzgerald et al, 1996; Bahuau et al, 1998; Randerson-Moor et al, 2001; Debniak et al, 2004; Mistry et al, 2005; Knappskog et al, 2006, Erlandson et al, 2007). To date, germline large deletions have been characterised at the 9p21 locus in only six families worldwide. A deletion involving CDKN2A exon1α, 2, and 3 and a deletion removing exon 1α and half of exon 2 were described in two melanoma-prone kindreds, originated from UK and from Norway, respectively (Mistry et al, 2005; Knappskog et al, 2006). Large deletions have also been found in families with combined proneness to melanoma and nervous system tumours (NST): a gross deletion ablating the whole CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes has been reported in a French family (Bahuau et al, 1998; Pasmant et al, 2007), and a deletion of p14ARF-specific exon 1β of the CDKN2A gene has been found in one US family and in two UK families (Bahuau et al, 1998; Randerson-Moor et al, 2001; Mistry et al, 2005; Laud et al, 2006). A large duplication of the CDKN2A/CDKN2B loci has also been reported in a melanoma patient from a Swedish family, but the clinical significance of this variant is not evident (Erlandson et al, 2007).

The purpose of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of large deletions at the 9p21 locus, which participated in CMM families originating from France, using the multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis (Schouten et al, 2002). This quantitative technique was used because it enabled fine-scale mapping at the CDKN2A locus and allowed other flanking genes to be screened (24 sites of interest on 9p in total). This approach led us to characterise a novel deletion of CDKN2A exon 2 (affecting both p14ARF and p16INK4a) in one patient. Moreover, it led to the identification of a new variant within the gene KLHL9 (Kelch-like 9) located approximately 630 kb from CDKN2A in another patient. Because this variant was not found in a control population, this finding prompted us to investigate this candidate in high-risk melanoma families with no mutation of CDKN2A.

Patients, materials and methods

Study participants

The patients in this study were enroled through the Department of Dermatology at the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave Roussy and the other French Hospitals that constitute the Familial Melanoma Study Group, as part of the French Familial Melanoma Project (Grange et al, 1995). A total of 214 index cases from independent pedigrees with at least two melanoma cases were identified between 1986 and 2005. These cases had confirmed diagnosis of CMM, through medical records, review of pathological material, and/or pathological reports. Among the 214 index cases, direct sequencing of CDKN2A (exon 1β, 1α, 2 and 3) or CDK4 (exon 2) had identified CDKN2A point mutations or small insertions/deletions in 46 families, and the CDK4 codon 24 point mutation in one family (Supplementary Table 1). The remaining 167 index cases were included in the present study to evaluate the contribution of large genomic deletions at 9p21 in the French series. Probands from these negative families displayed the following inclusion criteria: a) families with at least three affected members (‘high-risk family set’, N=42), (b) families with two first-degree relatives affected with confirmed melanoma (N=102), (c) families with two second degree relatives affected with confirmed melanoma (N=23). The mutation scanning of KLHL9 was performed in patients from the high-risk family set, including the 42 index cases and 48 additional affected members. Our control population consisted of 188 DNA samples prepared from lymphocytes of blood donors born in France. The study was approved by an institutional review board-approved protocol (CCPPRB no: 01-09-05, Paris Necker). It was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. All participating subjects signed informed consent before providing blood samples. DNA from participants was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes, using the QIAamp DNA Blood mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

Large insertion and deletion analysis

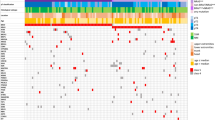

Deletion screening of the CDKN2A locus was carried out using the 9p21 Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification kit (P024), according to the supplied protocol (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) (Schouten et al, 2002; Mistry et al, 2005). The technique and preparation of the probes used in this kit are described elsewhere (Schouten et al, 2002; Mistry et al, 2005). Gene dosage quotients for 9 CDKN2A locus sites and for 15 other 9p genes sites were determined to screen for deletions at 9p. In total, 21 specific probes mapped to 9p21 (three within CDKN2B, three within MTAP, one within IFNA1, one within KIAA1354 (KLHL9), one within IFNW1, one within IFNB1, one within ELAVL2, one within TEK), two probes mapped to 9p22 (both within MLLT3) and one probe mapped to 9p24 (within FLJ00026 (DOCK8)).

Calculation of dosage quotients was carried out as described by Mistry et al (2005). Theoretically, gene dosage quotients close to 1.0 indicate two copies present (that is, wild-type); 0.5, one copy absent (that is, hemizygous); 0.0, both copies absent (that is, homozygous deletion); and 1.5, one copy duplicated. Quotients were scored according to observations made from known samples: wild type if the quotient was between 0.8 and 1.2, hemizygous deletion if the quotient was between 0.4 and 0.7, homozygous deletion if the quotient was between 0.0 and 0.2. All other values were considered undetermined.

RT–PCR analysis of CDKN2A transcripts

RNA from patient carrying the heterozygous CDKN2A deletion was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN), and cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using the Superscript reverse transcriptase system (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Characterisation of CDKN2A deletion breakpoint

Long-range PCRs were performed with the Expand™ Long Template PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer. Primers were designed to amplify the region encompassing the putative deletion between exon 1α and exon 3. Forward primer and reverse primer amplified a 355 bp mutant p16INK4-encoding cDNA fragment lacking exon 2, the wild type cDNA fragment being 662 bp long (Table 1). To characterise the intronic deletion breakpoints, forward primer in exon 1α and reverse primer in intron 2 amplified a 3705 bp genomic fragment for the wild type allele and a 770 bp fragment for the mutant allele (Table 1).

PCR products were sequenced with the Big Dye Terminator, version 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on the ABI Prism© 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Direct sequencing of KLHL9

Primers used for the sequencing of KLHL9 are given in Table 1. The amplification protocol consisted of 35 cycles with temperature steps at 94, 60, and 72°C for 30 s each.

Results

Contribution of genomic rearrangements at 9p21

Among the 167 index cases screened for genomic rearrangements at 9p21, 166 patients present a gene dosage quotient close to one (between 0.8 and 1.2), indicating no alteration in gene copy numbers, and one patient (0.6%) was identified to carry a hemizygous deletion of CDKN2A exon 2, as gene dosage quotient was close to 0.5. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification probes at exon 1β, exon1α and exon 3 of CDKN2A did not reveal a reduced gene dosage quotient for this patient, indicating that, according to position of probes within the exons, the deletion was at most 6.4 kb long with intronic breakpoints, extending at most from the first base of intron 1α to the last base of intron 2 (Figure 1A). These results were confirmed by quantitative multiplex PCR of short fluorescent fragments with primers specifically amplifying CDKN2A exon 1β, exon1α, exon 2 and exon 3 (data not shown) (Casilli et al, 2002). To verify whether or not the putative CDKN2A mutation generated aberrant mRNAs, long range PCR was performed on the patient cDNA. Sequencing of the PCR product confirmed that the germline deletion leads to an aberrant p16INK4a transcript, lacking the 307 bp corresponding to CDKN2A exon 2 (Figure 1). To determine the exact nature of the CDKN2A gene aberration, long range PCR and sequencing was performed on the patient's genomic DNA. This revealed a 2935 bp deletion extending from nucleotide position +1712 bp from end of exon 1α to position +873 bp from end of exon 2 (Figure 1). It is worth noting that the deletion breakpoints did not lie within ALU sequences, and that such repetitive elements could not explain the occurrence of a rearrangement at this genomic position.

Characterization of the new CDKN2A deletion. (A) Genemap of the CDKN2A locus. Breakpoints of the deletion (exon 1α +1712bp_exon 2 +873 bp) are indicated and illustrated by the sequence chromatogram. (B) Comparison of the wild type p16INK4A and p14ARF transcripts arising from the allele harbouring the deletion. The truncated transcripts are lacking exon 2. This alters the reading frame of both transcripts.

The patient carrying this novel deletion of CDKN2A presented with dysplastic nevus syndrome and developed five primary melanomas between 45 and 51 years of age. He was the index case of a melanoma-prone family of three affected members: his father had a confirmed diagnosis of melanoma at the age of 50, and his sister was also reported to have had melanoma, but no pathological report was available for her (Figure 2). We were unable to investigate the co-segregation of the genomic deletion with melanoma in this pedigree because of unavailability of biological material for the index case's relatives. In addition, the patient's uncle died of pancreatic cancer, a cancer that had been associated with CDKN2A germline mutations (Goldstein et al, 1995; Goldstein et al, 2006), and three other family members died of cancer, but no clinical details were reported to the clinician (Figure 2).

KLHL9 on 9p21 as a new candidate gene for susceptibility to melanoma

For a second patient diagnosed with melanoma at the age of 54, and belonging to a different melanoma -prone pedigree, a dosage quotient close to 0.5 was obtained for a 9p probe specific of the 5′ end of the transcription unit of the single exon gene KLHL9 (Kelch-like 9, previously named KIAA1354), suggesting a hemizygous deletion in this gene located about 630 kb telomeric from CDKN2A (Figure 3). Subsequent direct sequencing of the entire exon led to the identification of a heterozygous nucleotidic variation (A>G) located 16 bp upstream of the START codon of KLHL9 (NM_018847), that prevents the ligation reaction of the two contiguous probes used for MLPA, for the G allele (Figure 4). Although the various in silico tools (PupaSuite, http://pupasuite.bioinfo.cipf.es/, CorePromoter,http://rulai.cshl.org/tools/genefinder/CPROMOTER/, TFSEARCH, http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html, TESS, http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess) did not suggest that the presence of the G allele would have direct functional effects on the activity of the promoter, this new variant was not described in the public SNPs databases (ENSEMBL, http://www.ensembl.org/, dbSNP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP, and HAPMAP, http://www.hapmap.org/) and was absent in 188 unrelated controls from France (376 chromosomes). DNA was available for the two unaffected siblings of the patient, and MLPA and sequence analysis revealed that one of the patient's sisters, unaffected at age 62, also carried the –16 A>G allele. The father of the patient died of melanoma metastases to the brain at the age of 70, and his paternal grandmother had a suspicious pigmented lesion on her face and died of thyroid cancer at the age of 80. Unfortunately, material was not available for any of them, and co-segregation of the variant with skin lesion could not be investigated (Figure 5).

Identification of KLHL9 variant. (A) Principle of MLPA analysis: the patient carrying the variant shows a reduced amount of amplification product for probes specific of the promoter region of KLHL9. (B) Sequence chromatograms illustrating the nucleotidic change A>G at position –16 of the gene that prevents the ligation reaction.

Beside its genomic location at 9p21, KLHL9 appeared to represent a good candidate for melanoma susceptibility as it has been reported that loss of function of BTB/kelch repeat proteins may contribute to tumorigenesis (Adams et al, 2000; Liang et al, 2004; Yoshida, 2005). Therefore, we undertook the resequencing of the 4.3 kb unique exon of the gene in 90 CMM patients belonging to the high-risk family set (that is, families counting at least 3 CMM) with no CDKN2A or CDK4 mutation. The variant identified in the promoter of KLHL9 was not found in this series, and no other mutation elsewhere in the candidate gene was detected by direct sequencing.

Discussion

By adding a novel germline large deletion to the repertoire of germline CDKN2A mutations, our data contribute to an enlargement of the spectrum of mutations identified in melanoma-prone families and improve the estimate of the prevalence of this type of lesion, as the work was performed on the largest family dataset to date. Among the 214 melanoma-prone families recruited through the French Familial Melanoma Project, 46 families were positive for point mutations within CDKN2A (21.5%), one family carried a CDK4 point mutation in exon 2 (0.5%), and one family carried a large CDKN2A deletion (0.5%). Overall, a genetic alteration affecting either CDKN2A or CDK4 was detected in 48 of 214 (22.4%) of the French CMM families. Point mutations account for 97.9% (47 of 48), and large genomic rearrangements account for 2.1% (1 of 48) of CDKN2A/CDK4 mutations. The frequency of such alterations detectable by MLPA in CMM families negative for point mutations in CDKN2A and CDK4 (0.6%; 1 of 167 pedigrees screened) is even lower than frequencies reported in the UK population, 3.2% (3 of 93 pedigrees screened) (Mistry et al, 2005). Therefore, the question of systematic MLPA screening in pedigrees with no point mutations in the coding sequence of CDKN2A could be debated, as such screening will not improve substantially the sensitivity of genetic testing.

Owing to the overlapping open reading frames in exon 2, this deletion of CDKN2A is a new example of a germline mutation affecting p16 and p14 proteins, two major regulators of cell cycle progression and survival through the pRb and p53 pathways, respectively. The functional relevance of this genomic deletion is inferred based on three observations: (1) the knowledge that p16 proteins with less than 120 residues lack the capacity to bind to and inhibit CDK (Parry and Peters, 1996, Hashemi et al, 2000, 2002, 2) loss of CDKN2A exon 2 has been shown to reduce the activity of p14 (Hashemi et al, 2000, 2002, 3) both p14 and p16 mRNA lacking exon 2 are translated into truncated proteins when expressed exogenously (Hashemi et al, 2000). In addition, it is also possible that the CDKN2A exon 2 deletion leads to aberrant transcripts, which are the target of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay mechanism, thus preventing the synthesis of truncated p14 and p16.

Interestingly, three other gross deletions at the CDKN2A locus, impacting on both p16 and p14, have been reported from melanoma-NST families (Bahuau et al, 1998; Randerson-Moor et al, 2001; Mistry et al, 2005; Pasmant et al, 2007), and a splice site mutation removing CDKN2A exon 2 was also found in a melanoma/neurofibroma family (Petronzelli et al, 2001). However, there was no evidence of NST in the family with the novel CDKN2A deletion presented here, although clinical description of this family was very basic.

Methods used to screen for mutations in CDKN2A/ARF are usually PCR-based and focus on the detection of small sequences alterations, such as point mutations, small deletions and insertions. Few investigators have systematically searched for large CDKN2A/ARF deletions or rearrangements (Fitzgerald et al, 1996; Debniak et al, 2004; Mistry et al, 2005). We chose to apply MLPA analysis to determine whether large deletions or rearrangements occur at the CDKN2A/ARF locus on 9p21 in French CMM families; however, the failure to detect large deletions using this technique does not exclude the possibility that large deletions may exist, as the probes used do not cover the entire genomic sequence of CDKN2A. Moreover, neither inversions, nor translocations are detectable by this approach, and such genomic alterations cannot be ruled out in melanoma families where no CDKN2A mutation has been detected. Furthermore, the possibility of alteration at the transcript level in high-risk families with no mutation identified through conventional testing should be considered (Knappskog et al, 2006). As we did not employ RT–PCR, deep intronic mutations that have the potential to alter intron/exon splicing could have been missed. Finally, absence of CDKN2A mutation or large deletion does not rule out the possibility that epigenetic modification of either p16 or p14ARF could result in gene silencing that would contribute to melanoma (Merlo et al, 1995; Esteller et al, 2000). Such a germline epimutation silencing the DNA mismatch repair gene MLH1 has been reported in nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Suter et al, 2004; Hitchins et al, 2007).

In conclusion, although approximately 50% of melanoma-prone families display linkage to 9p21, only about half of these have been identified as carriers of mutations in the CDKN2A gene by direct exon sequencing (Hussussian et al, 1994; Kamb et al, 1994; Harland et al, 1997; Borg et al, 2000). Few of the melanoma-prone families tested here were sufficiently informative to assess for linkage to 9p21. However, the present work provides evidence that only a small fraction of the unexplained familial risk of CMM is attributable to large deletions of CDKN2A locus. Therefore, there may be yet unidentified highly penetrant melanoma susceptibility genes located at the 9p21 locus. The finding of the 5′UTR variant within KLHL9, located 630 kb from CDKN2A on 9p21 in one melanoma patient was serendipitous. Little is known about the biological function of KLHL9 itself, but Kelch-superfamily proteins participate in various cellular activities, and functions of family members impinge on cell morphology, cell organisation and gene expression. KLHL (kelch homologue) genes contain two evolutionary conserved domains: a broad-complex, tramtrack, bric-à-brac/proxvirus and zinc finger (BTB/POZ) domain, and a kelch motif, which is a human homologue of the Drosophila kelch gene. Kelch-like proteins are much conserved, and some family members have been implicated in embryogenesis and carcinogenesis through cytoskeleton organisation (Adams et al, 2000; Liang et al, 2004; Yoshida, 2005). Thus, as for other BTB/kelch repeat proteins, we hypothesized that loss of function of KLHL9 may contribute to tumorigenesis by promoting cell proliferation, suppressing apoptosis, and/or by affecting nuclear cytoskeleton dynamics. Although the 5′UTR variant within KLHL9 was absent in a French control population, we ruled out major involvement of KLHL9 in the susceptibility to melanoma by screening the entire coding sequence of the candidate gene in a panel of 42 high-risk CMM families. Recently, a new large antisense non coding RNA, named ANRIL, has been identified at the CDKN2A locus, with a first exon located in the promoter of the p14/ARF gene and overlapping the two exons of p15/CDKN2B (Pasmant et al, 2007). As ANRIL was localised within the 403 kb deletion in the French melanoma-NST family (Bahuau et al, 1998), it has been hypothesized that this new gene could be involved melanoma-NST syndrome families and in melanoma-prone families with no identified CDKN2A mutations. The possible involvement of ANRIL has not been investigated yet, and further studies should elucidate the role of this gene in the susceptibility to CMM.

Finally, efforts are currently underway to identify new high penetrance susceptibility genes on other chromosomes, as there remain a significant proportion of CMM families (∼50%) that are not linked to chromosome 9p21. Such genes may lie at 1p36 (Goldstein et al, 1993) and 1p22 (Gillanders et al, 2003).

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Adams J, Kelso R, Cooley L (2000) The kelch repeat superfamily of proteins: propellers of cell function. Trends Cell Biol 10: 17–24

Bahuau M, Vidaud D, Jenkins RB, Bieche I, Kimmel DW, Assouline B, Smith JS, Alderete B, Cayuela JM, Harpey JP, Caille B, Vidaud M (1998) Germ-line deletion involving the INK4 locus in familial proneness to melanoma and nervous system tumors. Cancer Res 58: 2298–2303

Borg A, Sandberg T, Nilsson K, Johannsson O, Klinker M, Masback A, Westerdahl J, Olsson H, Ingvar C (2000) High frequency of multiple melanomas and breast and pancreas carcinomas in CDKN2A mutation-positive melanoma families. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1260–1266

Casilli F, Di Rocco ZC, Gad S, Tournier I, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Frebourg T, Tosi M (2002) Rapid detection of novel BRCA1 rearrangements in high-risk breast-ovarian cancer families using multiplex PCR of short fluorescent fragments. Hum Mutat 20: 218–226

Chaudru V, Chompret A, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Spatz A, Avril MF, Demenais F (2004) Influence of genes, nevi, and sun sensitivity on melanoma risk in a family sample unselected by family history and in melanoma-prone families. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 785–795

Ciotti P, Struewing JP, Mantelli M, Chompret A, Avril MF, Santi PL, Tucker MA, Bianchi-Scarrà G, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Goldstein AM (2000) A single genetic origin for the G101W CDKN2A mutation in 20 melanoma-prone families. Am J Hum Genet 67: 311–319

Debniak T, Gorski B, Scott RJ, Cybulski C, Medrek K, Zowocka E, Kurzawski G, Debniak B, Kadny J, Bielecka-Grzela S, Malekszka R, Lubinski J (2004) Germline mutation and large deletion analysis of the CDKN2A and ARF genes in families with multiple melanoma or an aggregation of malignant melanoma and breast cancer. Int J Cancer 110: 558–562

Erlandson A, Appelqvist F, Wennberg AM, Holm J, Enerback C (2007) Novel CDKN2A mutations detected in Western Swedish families with hereditary malignant melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 127: 1465–1467

Esteller M, Tortola S, Toyota M, Capella G, Peinado MA, Baylin SB, Herman JG (2000) Hypermethylation-associated inactivation of p14(ARF) is independent of p16(INK4a) methylation and p53 mutational status. Cancer Res 60: 129–133

Fitzgerald MG, Harkin DP, Silva-Arrieta S, MacDonald DJ, Lucchina LC, Unsal H, O′Neill E, Koh J, Finkelstein DM, Isselbacher KJ, Sober AJ, Haber DA (1996) Prevalence of germline mutations in p16, p19ARF, and CDK4 in familial melanoma: analysis of a clinic-based population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 8541–8545

Gillanders E, Juo SH, Holland EA, Jones M, Nancarrow D, Freas-Lutz D, Sood R, Park N, Faruque M, Markey C, Kefford RF, Palmer J, Bergman W, Bishop DT, Tucker MA, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Hansson J, Stark M, Gruis N, Bishop JN, Goldstein AM, Bailey-Wilson JE, Mann GJ, Hayward N, Trent J, Lund Melanoma Study Group; Melanoma Genetics Consortium (2003) Localization of a novel melanoma susceptibility locus to 1p22. Am J Hum Genet 73: 301–313

Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Cannon-Albright LA, Skolnick MH (1994) Systematic population-based assessment of cancer risk in first-degree relatives of cancer probands. J Nat Cancer Inst 86: 1600–1608

Goldstein AM, Chan M, Harland M, Gillanders EM, Hayward NK, Avril MF, Azizi E, Bianchi-Scarra G, Bishop DT, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Bruno W, Calista D, Cannon Albright LA, Demenais F, Elder DE, Ghiorzo P, Gruis NA, Hansson J, Hogg D, Holland EA, Kanetsky PA, Kefford RF, Landi MT, Lang J, Leachman SA, Mackie RM, Magnusson V, Mann GJ, Niendorf K, Newton Bishop J, Palmer JM, Puig S, Puig-Butille JA, de Snoo FA, Stark M, Tsao H, Tucker MA, Whitaker L, Yakobson E, Melanoma Genetics Consortium (GenoMEL) (2006) High-risk melanoma susceptibility genes and pancreatic cancer, neural system tumors, and uveal melanoma across GenoMEL. Cancer Res 66: 9818–9828

Goldstein AM, Chaudru V, Ghiorzo P, Badenas C, Malvehy J, Pastorino L, Laud K, Hulley B, Avril MF, Puig-Butille JA, Miniere A, Marti R, Chompret A, Cuellar F, Kolm I, Mila M, Tucker MA, Demenais F, Bianchi-Scarra G, Puig S, de-Paillerets BB (2007) Cutaneous phenotype and MC1R variants as modifying factors for the development of melanoma in CDKN2A G101W mutation carriers from 4 countries. Int J Cancer 121: 825–831

Goldstein AM, Dracopoli NC, Ho EC, Fraser MC, Kearns KS, Bale SJ, McBride OW, Clark Jr WH, Tucker MA (1993) Further evidence for a locus for cutaneous malignant melanoma-dysplastic nevus (CMM/DN) on chromosome 1p, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet 52: 537–550

Goldstein AM, Fraser MC, Struewing JP, Hussussian CJ, Ranade K, Zametkin DP, Fontaine LS, Organic SM, Dracopoli NC, Clark Jr WH, Tucker MA (1995) Increased risk of pancreatic cancer in melanoma-prone kindreds with p16INK4 mutations. N Engl J Med 333: 970–974

Gonzalgo ML, Bender CM, You EH, Glendening JM, Flores JF, Walker GJ, Hayward NK, Jones PA, Fountain JW (1997) Low frequency of p16/CDKN2A methylation in sporadic melanoma: comparative approaches for methylation analysis of primary tumors. Cancer Res 57: 5336–5347

Grange F, Chompret A, Guilloud-Bataille M, Guillaume JC, Margulis A, Prade M, Demenais F, Avril MF (1995) Comparison between familial and nonfamilial melanoma in France. Arch Dermatol 131: 1154–1159

Harland M, Meloni R, Gruis N, Pinney E, Brookes S, Spurr NK, Frischauf A-M, Bataille V, Peters G, Cuzick J, Selby P, Bishop DT, Bishop JN (1997) Germline mutations of the CDKN2 gene in UK melanoma families. Hum Mol Genet 6: 2061–2067

Hashemi J, Lindstrom MS, Asker C, Platz A, Hansson J, Wiman KG (2002) A melanoma-predisposing germline CDKN2A mutation with functional significance for both p16 and p14ARF. Cancer Lett 180: 211–221

Hashemi J, Platz A, Ueno T, Stierner U, Ringborg U, Hansson J (2000) CDKN2A germ-line mutations in individuals with multiple cutaneous melanomas. Cancer Res 60: 6864–6867

Hayward NK (2003) Genetics of melanoma predisposition. Oncogene 22: 3053–3062

Hemminki K, Zhang H, Czene K (2003) Familial and attributable risks in cutaneous melanoma: effects of proband and age. J Invest Dermatol 120: 217–223

Hitchins MP, Wong JJ, Suthers G, Suter CM, Martin DI, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL (2007) Inheritance of a cancer-associated MLH1 germ-line epimutation. N Engl J Med 356: 697–705

Hussussian CJ, Struewing JP, Goldstein AM, Higgins PAT, Ally DS, Steahan MD, Clark Jr WH, Tucker MA, Dracopoli NC (1994) Germline p16 mutations in familial melanoma. Nat Genet 8: 15–21

Kamb A, Shattuck-Eidens D, Eeles R, Liu Q, Gruis NA, Ding W, Hussey C, Tran T, Miki Y, Weaver-Feldhaus J, McClure M, Aitken JF, Anderson DE, Bergman W, Frants R, Goldgar DE, Green A, MacLennan R, Martin NG, Meyer LJ, Youl P, Zone JJ, Skolnick MH, Cannon-Albright LA (1994) Analysis of the p16 gene (CDKN2) as a candidate for the chromosome 9p melanoma susceptibility locus. Nat Genet 8: 23–26

Kannengiesser C, Brookes S, Gutierrez del Arroyo A, Pham D, Bombled J, Barrois M, Mauffret O, Avril MF, Chompret A, Lenoir GM, Sarasin A, French Hereditary Melanoma Study Group, Peters G, Bressac-de Paillerets B (2008) Functional, structural and genetic evaluation of 20 CDKN2A germ line mutations identified in melanoma-prone families or patients. Hum Mutat, (in press)

Kannengiesser C, Dalle S, Leccia MT, Avril MF, Bonadona V, Chompret A, Lasset C, Leroux D, Thomas L, Lesueur F, Lenoir G, Sarasin A, Bressac-de Paillerets B (2007) New founder germline mutations of CDKN2A in melanoma-prone families and multiple primary melanoma development in a patient receiving levodopa treatment. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 46: 751–760

Knappskog S, Geisler J, Arnesen T, Lillehaug JR, Lonning PE (2006) A novel type of deletion in the CDKN2A gene identified in a melanoma-prone family. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 45: 1155–1163

Laud K, Marian C, Avril MF, Barrois M, Chompret A, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Clark PA, Peters G, Chaudru V, Demenais F, Spatz A, Smith MW, Lenoir GM, Bressac-de Paillerets B, French Hereditary Melanoma Study Group (2006) Comprehensive analysis of CDKN2A (p16INK4A/p14ARF) and CDKN2B genes in 53 melanoma index cases considered to be at heightened risk of melanoma. J Med Genet 43: 39–47

Liang XQ, Avraham HK, Jiang S, Avraham S (2004) Genetic alterations of the NRP/B gene are associated with human brain tumors. Oncogene 23: 5890–5900

Merlo A, Herman JG, Mao L, Lee DJ, Gabrielson E, Burger PC, Baylin SB, Sidransky D (1995) 5′ CpG island methylation is associated with transcriptional silencing of the tumour suppressor p16/CDKN2/MTS1 in human cancers. Nature Med 1: 686–692

Mistry SH, Taylor C, Randerson-Moor JA, Harland M, Turner F, Barrett JH, Whitaker L, Jenkins RB, Knowles MA, Bishop JA, Bishop DT (2005) Prevalence of 9p21 deletions in UK melanoma families. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 44: 292–300

Molven A, Grimstvedt MB, Steine SJ, Harland M, Avril MF, Hayward NK, Akslen LA (2005) A large Norwegian family with inherited malignant melanoma, multiple atypical nevi, and CDK4 mutation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 44: 10–18

Parry D, Peters G (1996) Temperature-sensitive mutants of p16CDKN2 associated with familial melanoma. Mol Cell Biol 16: 3844–3852

Pasmant E, Laurendeau I, Heron D, Vidaud M, Vidaud D, Bieche I (2007) Characterization of a germ-line deletion, including the entire INK4/ARF locus, in a melanoma-neural system tumor family: identification of ANRIL, an antisense noncoding RNA whose expression coclusters with ARF. Cancer Res 67: 3963–3969

Petronzelli F, Sollima D, Coppola G, Martini-Neri ME, Neri G, Genuardi M (2001) CDKN2A germline splicing mutation affecting both p16(ink4) and p14(arf) RNA processing in a melanoma/neurofibroma kindred. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 31: 398–401

Platz A, Hansson J, Mansson-Brahme E, Lagerlof B, Linder S, Lundqvist E, Sevigny P, Inganas M, Ringborg U (1997) Screening of germline mutations in the CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes in Swedish families with hereditary cutaneous melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 89: 697–702

Randerson-Moor JA, Harland M, Williams S, Cuthbert-Heavens D, Sheridan E, Aveyard J, Sibley K, Whitaker L, Knowles M, Newton BJ, Bishop DT (2001) A germline deletion of p14(ARF) but not CDKN2A in a melanoma-neural system tumour syndrome family. Hum Mol Genet 10: 55–62

Ruiz A, Puig S, Lynch M, Castel T, Estivill X (1998) Retention of the CDKN2A locus and low frequency of point mutations in primary and metastatic cutaneous malignant melanoma. Int J Cancer 76: 312–316

Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G (2002) Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e57

Soufir N, Avril MF, Chompret A, Demenais F, Bombled J, Spatz A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, the French Familial Melanoma Study Group, Bénard J, Bressac-de Paillerets B (1998) Prevalence of p16 and CDK4 germline mutations in 48 melanoma-prone families in France. Hum Mol Genet 7: 209–216

Suter CM, Martin DI, Ward RL (2004) Germline epimutation of MLH1 in individuals with multiple cancers. Nat Genet 36: 497–501

Wagner SN, Wagner C, Briedigkeit L, Goos M (1998) Homozygous deletion of the p16INK4a and the p15INK4b tumour suppressor genes in a subset of human sporadic cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol 138: 13–21

Yakobson E, Eisenberg S, Isacson R, Halle D, Levy-Lahad E, Catane R, Safro M, Sobolev V, Huot T, Peters G, Ruiz A, Malvehy J, Puig S, Chompret A, Avril MF, Shafir R, Peretz H, Bressac-de Paillerets B (2003) A single Mediterranean, possibly Jewish, origin for the Val59Gly CDKN2A mutation in four melanoma-prone families. Eur J Hum Genet 11: 288–296

Yoshida K (2005) Identification and characterization of a novel kelch-like gene KLHL15 in silico. Oncol Rep 13: 1133–1137

Zuo L, Weger J, Yang Q, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Walker GJ, Hayward N, Dracopoli NC (1996) Germline mutations in the p16INK4a binding domain of CDK4 in familial melanoma. Nat Genet 12: 97–99

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the families who have so willingly participated in this study and the clinicians who identified these families. This work was funded by Ligue Contre le Cancer (Comité du Val de Marne 2003–2004 and Ligue Nationale PRE2005.LNCC/FD1), ARC (Grant no: 3222, 2003), and INCA - Cancéropole Ile de France (melanoma network RS no. 13). FL was recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (UFP20051105597).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lesueur, F., de Lichy, M., Barrois, M. et al. The contribution of large genomic deletions at the CDKN2A locus to the burden of familial melanoma. Br J Cancer 99, 364–370 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604470

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604470

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

E2F1 copy number variations in germline and breast cancer: a retrospective study of 222 Italian women

Molecular Medicine (2021)

-

The Future of Molecular Analysis in Melanoma: Diagnostics to Direct Molecularly Targeted Therapy

American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (2016)

-

A large de novo9p21.3 deletion in a girl affected by astrocytoma and multiple melanoma

BMC Medical Genetics (2014)

-

Contribution of CDKN2A/P16 INK4A, P14 ARF, CDK4 and BRCA1/2 germline mutations in individuals with suspected genetic predisposition to uveal melanoma

Familial Cancer (2010)