Abstract

Aims To estimate the incidence of acute-onset presumed infectious endophthalmitis (PIE) following cataract surgery in the UK and provide epidemiological data on the presentation, management, microbiology, and outcome of cases of endophthalmitis.

Methods Cases were identified prospectively by active surveillance through the British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit reporting card system, for the 12-month period October 1999 to September 2000 inclusive. Questionnaire data were obtained from ophthalmologists throughout the UK at baseline and 6 months after diagnosis. Under-reporting was estimated by independently contacting units with infection databases.

Results Data were available on 213 patients at baseline and 201 patients at follow-up. The minimum estimated incidence of PIE was 0.086 per 100 cataract extractions and the corrected incidence was 0.14 per 100 cataract extractions. For the management of PIE, 96% of patients received intravitreal, 30% subconjunctival, 65% oral, and 17% intravenous antibiotics. In all, 17% of patients received intravitreal steroid. From the intraocular samples taken for microbiological analysis, 56% were culture positive. At follow-up, 48% of patients achieved visual acuity of 6/12 or better and 66% achieved better than 6/60. 13% of patients were unable to perceive light or had evisceration of the globe.

Conclusions The incidence of PIE after cataract surgery in the UK is comparable to that of other studies. Approximately 50% of patients achieved a visual acuity close to the driving standard.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cataract extraction is now one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the UK. Rehabilitation following cataract surgery is rapid with good visual outcome in the majority of cases and relatively few complications. Patient expectation of visual improvement following cataract surgery is high, therefore the incidence and outcomes of sight-threatening complications need to be known for appropriate informed consent prior to surgery.

Endophthalmitis is potentially the most devastating complication of cataract surgery and despite optimal management the visual outcome is poor in many cases. Although the incidence of this complication is not known precisely, data from studies performed over the past 12 years suggest that the risk of endophthalmitis is one case per 312-1250 cataract extractions.1,2,3,4 Owing to the variation in these reported incidence figures and also because some of the results were based on intracapsular and extracapsular cataract extractions, there is a need for further information on the incidence of endophthalmitis following modern cataract surgery in the UK.

The present study was undertaken to assess various epidemiological aspects of acute-onset endophthalmitis following cataract surgery in a national prospective UK survey.

Materials and methods

This was a population-based, prospective study with active surveillance of cases through the British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit (BOSU) monthly reporting card system. The BOSU was established to assist in the investigation of the incidence and clinical features of rare eye conditions of public health or scientific importance. The protocols for individual studies are reviewed by the BOSU steering committee in order that the above criteria may be met and also to provide advice to individual research workers on the design of their studies.

The BOSU surveillance scheme involves all consultant or associate specialist ophthalmologists with clinical autonomy in the UK who form the reporting base. Ophthalmologists were asked to notify the study investigators, through the BOSU, of a newly diagnosed case of acute presumed infectious endophthalmitis (PIE) following cataract surgery. Case notification was requested for the 12-month study period between October 1999 and September 2000 inclusive. Acute-onset endophthalmitis was defined as any patient with a clinical diagnosis of PIE occurring within 6 weeks of cataract surgery.3 All combined procedures, cases of previous intraocular surgery and trauma were excluded.

Following case notification to the BOSU, every reporting ophthalmologist was sent a detailed questionnaire by the study investigators requesting data on previous medical and ophthalmic history, cataract surgery details, endophthalmitis presentation details, microbiology, and management. Outcome data were obtained from follow-up questionnaires sent to the reporting ophthalmologists 6 months after diagnosis. Ophthalmologists who did not return questionnaires received reminder letters at 2 and 3 months after the initial questionnaire was sent.

In order to estimate the completeness of case ascertainment throughout the UK, other sources of case ascertainment were sought as a means of external validation. A total of 38 units (20%) were selected randomly from a list of UK centres. The Clinical Director from each unit was contacted to enquire if infection databases were kept or if postoperative endophthalmitis audits had been performed during the study period. Data were requested from units that kept databases and were willing to provide information for this study. The information requested included: the date of cataract surgery, date of diagnosis with PIE and a patient ‘identifier’, for example, date of birth, to compare with the study baseline data. To estimate under-reporting, the total number of cases per centre was compared with the total number of cases reported to BOSU for that same centre.

Results

BOSU reports

From October 1999 to September 2000 inclusive, 300 reports of patients with PIE following cataract surgery were made to BOSU by 199 ophthalmologists in the UK. In addition, 10 reports were received directly by the study investigators resulting in a total of 310 reports for the 12-month study period. Questionnaires were received from 285/310 reports (92% response rate), of these 72 were excluded (31 were duplicate reports and 41 were incorrectly diagnosed or did not satisfy inclusion criteria for diagnosis, see Methods). In addition, 14 reports were confirmed as cases by the reporting ophthalmologist, although no further information was available. Questionnaire data were available on 213 patients at baseline and 201 patients at follow-up.

Estimate of ascertainment

Nine centres provided information from infection databases.. These centres included six Teaching and three District General Hospitals with an average of 8.8 ophthalmic consultants per unit (range 5–13). During the study period, 40 cases of PIE were reported to BOSU from these nine centers; however, information from infection databases in these centres revealed a total of 64 cases (range 4–11 per centre). Assuming this sample of centres is representative of units throughout the UK, we estimated that 62.5% of cases of PIE following cataract surgery in the UK were reported to the BOSU (95% confidence limits 54%, 71%). This estimation of under-reporting is in close approximation to the study period BOSU 4-month mean card return rate of 71%.5

Incidence rates

For the purposes of incidence estimation, only cases of PIE following cataract surgery performed on the NHS were included in the calculations, as the number of cataract extractions in private practice, performed annually in the UK, is not known. Of the 227 verified cases, 196 patients had cataract surgery performed on the NHS.

The number of NHS cataract extractions performed during the study period was estimated from half the total number of operations for the 2-year period between April 1999 and March 2001, excluding combined procedures (figures obtained from the Department of Health in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). Based on these estimates, the total number of NHS cataract extractions for the study period was 230 000 (approximated to the nearest 1000).

The incidence of PIE following cataract surgery in the UK, based on reports to the BOSU, is 0.085% (95% CI 0.073%, 0.097%).

We estimated that 62.5% of cases were reported to the BOSU, therefore adjusting for under-reporting the expected number of cases during the study period is approximately 314 (95% CI 252, 376). The corrected incidence of PIE following cataract surgery in the UK is 0.14% (95% CI 0.11%, 0.17%) or approximately one case per 750 (95% CI 1:625, 1:878) cataract extractions.

Cataract surgery details

The majority of patients were greater than 70 years of age (mean=73.5,. median=76, range=7–94), one patient was aged less than 20 years (age 7 years). Women formed 61% of the patients. There was a history of diabetes in 10% and immunosuppression (leukaemia, lymphoma, and myelodysplasia) in 4%. In all, 4% of patients were taking oral steroids and 9% of patients were taking topical treatment for glaucoma at the time of cataract surgery.

Table 1 presents details of the cataract surgery for patients presenting with PIE. The intraocular lenses (IOLs) inserted at the time of cataract surgery were mostly foldable lenses with optics made from silicone {73/210 (35%)} and acrylic {93/210 (44%)}. IOL optics made from PMMA were used in 40/210 (19%) cases. No IOL was inserted in 4/210 (2%) cases. The predominant haptic material was PMMA {100/154 (65%)}. 12 (8%) cases had IOLs inserted with polypropylene haptics.

The operative and first day postoperative complications are presented in Table 2. The percentage of cases with intraoperative capsule rupture was higher (10%) in this group of patients compared to patients undergoing cataract surgery in the national cataract surgery survey4 (4.4%). Intraoperative capsular rupture and other possible risk factors for endophthalmitis are being investigated in a separate case–control study.

Endophthalmitis cases—baseline characteristics

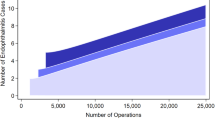

The majority of patients (81%) presented within the first week of cataract surgery, 95% presented within 18 days, and 97.5% within 23 days of cataract surgery. Figures 1, 2 compare baseline characteristics with the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS).6 Almost all patients had symptoms at presentation, with blurred vision being the most common in 85%. Pain was reported by 69% of patients, which was similar to the EVS. Examination revealed an anterior chamber hypopyon in 72%, no red reflex in 39% and an afferent pupillary defect in 23% of recorded cases.

As expected, most patients had poor presenting visual acuity, with 85% having acuity of equal to or less than 6/60 (range=6/6 — NPL, median=HM). Initial visual acuity was PL in 20% and NPL in 1.5% of patients.

Management of PIE

A total of 202 (94%) patients had an aqueous or vitreous biopsy attempted at presentation and one patient had a delayed biopsy. Samples for microbiology were obtained in 199 patients, 72 (36%) had vitreous biopsy only, 16 (8%) only aqueous biopsy, and 111 (56%) both aqueous and vitreous biopsies. The vitreous sampling technique was recorded in 180 patients; 113 (63%) had a vitreous aspiration with a needle and 67 (37%) had a vitreous biopsy using an ocutome.

In total, 96% (205/213) of patients received immediate or delayed intravitreal antibiotics, eight (4%) patients were not given intravitreal antibiotics and one patient had evisceration of the globe on presentation. From the 205 patients receiving intravitreal antibiotics, 42 (20%) required a second injection of antibiotic and three (1.5%) received a third injection. The majority of patients received a combination of vancomycin and amikacin {113/205 (55%)} or vancomycin and ceftazidime {56/205 (27%)}. Other intravitreal antibiotic combinations included: teicoplanin/ciprofloxacin (3%), vancomycin/cefuroxime (3%), vancomycin/gentamicin (1.5%), vancomycin/ciprofloxacin (1%), and cefuroxime/gentamicin (1%).

A total of 64 (30%) patients received subconjunctival antibiotics, 139/212 (66%) oral antibiotics, 36/212 (17%) intravenous (i.v.) antibiotics, 21/212 (10%) oral and i.v. antibiotics for the management of PIE. Most patients (92%) also received topical antibiotics.

In addition to intravitreal antibiotic, 37/212 (17%) patients received intravitreal steroid. Of all, 29 patients were given intravitreal steroid as part of the initial management and eight patients received a delayed injection of steroid.

In total, 46 (22%) patients received subconjunctival steroid (33% subconjunctival dexamethasone, 67% subconjunctival betnesol). Systemic oral steroid was given to 90/212 (42%) patients and two of these patients also received i.v. steroid.

Microbiological results

From the 199 patients who had aqueous or vitreous biopsies, microbial growth was reported from samples in 111 (56%) patients (Figure 3). Gram-positive organisms were isolated in 103/199 (52%) patients and Gram-negative organisms in 8/199 (4%) patients. Isolates were more likely to grow from vitreous samples (53% [97/182]) than from aqueous samples (29% [36/126]). The culture positive rate from both aqueous and vitreous samples was 133/308 (43%). When both aqueous and vitreous samples were taken, 8/111 (7%) of patients had a positive culture from the aqueous but not from the vitreous. Interestingly, pseudomonas was cultured from the aqueous sample but not the vitreous in 3/5 (60%) of the pseudomonas isolates reported.

The percentages of positive cultures according to the vitreous sampling technique were as follows: vitreous aspiration with a needle, 63/113 (56%) and vitreous biopsy by ocutome, 37/67 (55%).

Vitrectomy

A total of 39 (18%) patients required a vitrectomy procedure (PPV) as part of their management. Of these, 15 (7%) patients had a PPV performed as part of the initial management of PIE (three of these patients required a second PPV and two patients required a third PPV) and 24/213 (11%) patients had a delayed PPV (four required a further PPV).

In all, 42 (20%) patients presented with visual acuity of perception of light (PL). From these patients, 13 (31%) had a PPV performed; 5/42 (12%) immediately (at presentation) and 8/42 (19%) delayed (more than 1 day after presentation).

Further additional procedures performed and the ocular complications noted at follow-up are summarized in Table 3.

Outcome

Visual acuity outcomes from follow-up data were available on 201 patients. The mean time from diagnosis to follow-up was 180 days (median=180, range 18–459).

At follow-up, 96/201 (48%) patients achieved visual acuity of 6/12 or better, 68/201 (34%) achieved 6/60 or worse, and 26/201 (13%) patients were NPL or had evisceration of the globe.

Some patients had reduced visual acuity as a consequence of ocular complications that developed after recovery from PIE (Table 3). Macular abnormalities were found in 41/201 (20%) patients and included: macular pucker {9% (19/201)}, cystoid macular oedema, retinal pigment epithelial abnormalities, and macular holes. Ocular comorbidity existed in some patients; pre-existing age-related macular degeneration in 5/201 (2.5%) cases and diabetic maculopathy in 1/201 (0.5%).

Poor visual outcome (less than or equal to 3/60) occurred in 6/8 (75%) and 22/36 (61%) cases, where Gram-negative organisms and streptococcus species were cultured, respectively. More patients with culture negative ocular samples {16/88 (18%)} had a poor visual outcome compared to patients who had positive cultures for coagulase-negative staphylococci {6/54 (11%)}.

Discussion

This national prospective study, in association with the BOSU, provides an estimate of the incidence of PIE following cataract surgery in the UK. The corrected incidence figure of 0.14% is comparable with data from other studies.1,2,3,4

The BOSU employs a systematic, prospective, case ascertainment system, which is the best approach to identifying cases of interest. Evaluation trials comparing passive and active surveillance systems consistently report that participants in an active scheme notify around twice as many cases per head of population.7,8

Sources of error

Underascertainment of cases is a methodological feature of routine surveillance that uses a single source to identify cases. Assessments of the completeness of reporting and reasons for underascertainment are necessary to estimate their effect. The gold standard of an alternative independent routine source to identify cases was not available. Data from nine centres that kept infection databases provided an estimate of ascertainment to be 62.5%. The mean card return rate to the BOSU for the 12-month study period was 71%,5 which provides an additional indicator of compliance.

These estimates of ascertainment are lower than estimates for previous BOSU studies (range between 75 and 95%)5 and will have different causes. The BOSU reporting scheme is dependent on voluntary reporting and a proportion of the underascertainment will be attributable to random errors (eg forgetting to report a case), which reduces the incidence estimate, but does not bias the data. Systematic under-reporting will have biased the data and barriers to participation in the surveillance scheme have been reported.5 Furthermore, study-specific factors could be due to difficulties with the interpretation of the case definition,9 management by nonconsultant ophthalmologists or reluctance by participating ophthalmologists to report postoperative complications such as endophthalmitis.

While this study has not identified all cases, it is likely that all previous studies will have been subject to similar or greater unevaluated sources of error.

Case definition

Although our case definition included cases diagnosed with PIE within 6 weeks of surgery, the majority of cases in this study presented within the first 3 weeks of surgery. Six weeks was chosen as we were mainly interested in the acute-onset cases. There is no fixed definition for the division between early- and delayed-onset postoperative endophthalmitis; some authors identify this as between 4 and 6 weeks after surgery.3,10 Acute-onset cases tend to present in a different manner to the chronic cases and are also managed differently with generally a worse visual outcome. Fisch et al1 found that 72 and 92% of patients presented with endophthalmitis within 17 and 60 days of cataract surgery, respectively. Olson et al11 estimated that 88% of patients present within 6 weeks of surgery. Therefore, approximately 10–20% of patients in our study with a delayed-onset-type endophthalmitis were not included in the incidence calculation.

Case ascertainment was dependent on a clinical diagnosis of PIE. Some of the cases reported to the BOSU may have been severe postoperative inflammation rather than ‘true’ infectious endophthalmitis. The differentiation between these two clinical presentations can be difficult, but whenever postoperative infectious endophthalmitis is suspected the patient should always be managed as PIE. Should subsequent microbiological cultures prove to be negative, this still does not rule out an infectious aetiology as a significant percentage of infectious cases are not bacteriologically identified by using conventional culture techniques.12,13,14 One recent study showed that by using the polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of bacterial endophthalmitis, 54.8% more samples were positive for bacteria compared to conventional culture methods.14

Both culture negative and culture positive cases were therefore included in the data analysis for this study.

Microbiology

The majority of patients (93%) had ocular samples taken for microbiological analysis. Both vitreous and aqueous samples were obtained in 56%, only vitreous samples in 36%, and only aqueous samples in 8% of these patients. Vitreous samples are more likely to yield positive cultures than aqueous samples,15 however as in this study, cases with a positive aqueous tap and negative vitreous tap have been described.15 In order to improve the culture positive yield both vitreous and aqueous samples should be obtained from patients with PIE. The vitreous sampling technique did not affect the culture rate as the percentage of positive cultures was almost identical for eyes having vitreous aspiration by needle (56%) compared to eyes having vitreous biopsy by ocutome (55%).

The culture positive rate for patients who had ocular samples taken was 56% compared to 69% in the EVS. The reasons for this reduced culture rate from our UK survey may be due to the fact that all patients enrolled in the EVS had aqueous and vitreous taps performed, thereby improving the culture positive yield. Also, not all patients in this UK survey had samples cultured on enrichment media, whereas all EVS specimens were inoculated onto enrichment media as well as agar plates.

Less coagulase-negative staphylococci (49 vs 70%) and more streptococci (32 vs 9%) were cultured from samples in this study compared to the EVS. This difference in bacterial species identified may be explained by the exclusion criteria used in the EVS. Patients were excluded because of an excessively cloudy cornea/anterior chamber or presenting visual acuity of NPL vision, therefore some infections caused by the more virulent organisms such as streptococci were excluded from the EVS analysis.

Patients with infections caused by the more virulent bacteria present earlier than those with less virulent infections,10 which may explain why a greater percentage of patients in this study presented earlier after cataract surgery compared to the patients in the EVS (Figure 1).

Management

Treatment of endophthalmitis should be initiated as soon as possible, once the diagnosis is suspected. Peyman16 noted that no eyes were salvaged in experimental models when intravitreal antibiotic treatment was delayed for 24 h or more after the inoculation of bacteria into the vitreous cavity.

A survey performed in 1985 of UK consultant practice in the management of endophthalmitis showed that 74% of respondents did not inject intravitreal antibiotics.17 Following the results of recent studies,6,18 it is now accepted that direct injection of antibiotics into the vitreous cavity is the most consistent method of achieving adequate intraocular levels for the treatment of suspected infectious endophthalmitis.

The majority of patients (96%) in this study received intravitreal antibiotics for the management of PIE. Most patients were given vancomycin and amikacin or ceftazidime. Teicoplanin was used in 3% of patients as an alternative intravitreal antibiotic for Gram-positive organisms. Teicoplanin has a spectrum of activity similar to that of vancomycin but is more active than vancomycin against streptococci.19 The antibiotic of choice for Gram-negative coverage is controversial because of the reported cases of macular infarction after intraocular administration of either gentamicin or amikacin.20

Eight (4%) patients did not receive intravitreal antibiotics even though presenting visual acuity was less than 6/60 in 75% (6/8). Nonadministration of intravitreal antibiotics in patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of PIE following cataract surgery can have disastrous consequences as 25% (2/8) of the patients who did not receive intravitreal antibiotics had a final visual acuity of NPL.

The role of i.v. antibiotics in the treatment of endophthalmitis appeared to have been partly defined by the EVS.6 Despite the EVS conclusions that systemic antibiotics did not provide benefit in the management of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery,6 65% of patients in this survey received adjunctive oral antibiotics and 17% adjunctive intravenous antibiotics.

The use of intravitreal steroid in the management of PIE is controversial and is reflected in this survey, whereby only 17% of patients received intravitreal dexamethasone or betamethasone. Dexamethasone is a potent inhibitor of many of the inflammatory mediators that are produced as a result of the intraocular infection. Based on experimental studies in rabbits the use of intravitreal dexamethasone in addition to vancomycin results in significantly less intraocular inflammation and more preservation of retinal tissue than eyes treated with vancomycin alone.21

In a recent trial, patients who received intravitreal steroid for the treatment of postoperative endophthalmitis had a significantly reduced likelihood of obtaining a three-line improvement in visual acuity.22 This was a retrospective, nonrandomized, comparative trial, and was criticized for bias towards selection of patients with more severe intraocular inflammation receiving intravitreal steroid.23

The use of intravitreal steroid in the treatment of endophthalmitis requires evaluation by a randomized, controlled study. Oral prednisolone is an alternative but is associated with systemic side effects.

Most UK ophthalmologists do not appear to follow the EVS recommendations that vitrectomy is beneficial in eyes with PL vision. Approximately 70% of patients presenting with PL vision did not undergo PPV in this study.

Nearly 50% of patients achieved visual acuity close to the driving standard. Of the patients, 13% were NPL or had evisceration of the globe at follow-up, compared to 5% of patients in the EVS. Again, this difference in visual outcome can be explained by the exclusion criteria used in the EVS, whereby some of the more severe cases of endophthalmitis were excluded.

A large amount of data associated with postoperative endophthalmitis were collected during this survey. In order to investigate possible risk factors for endophthalmitis, using a case–control methodology, data were also collected from patients undergoing cataract surgery in randomly selected units throughout the UK. The results of this analysis will be reported separately.

During this survey, we found that few centres kept records of postoperative infections. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists guidelines on clinical governance in ophthalmology require that endophthalmitis following surgery, as a Critical Incident, should be recorded.24 Future national epidemiological studies of postoperative endophthalmitis would benefit if units throughout the UK kept databases on all postoperative infections.

The results of this survey provide valuable information for UK ophthalmologists to discuss with patients the risks involved prior to cataract surgery.

References

Fisch A, Salvanet A, Prazuck T, Forestier F, Gerbaud L, Coscas G et al. Epidemiology of infective endophthalmitis in France. The French Collaborative Study Group on Endophthalmitis. Lancet 1991; 338 (8779): 1373–1376.

Schmitz S, Dick HB, Krummenauer F, Pfeiffer N . Endophthalmitis in cataract surgery: results of a German survey. Ophthalmology 1999; 106 (10): 1869–1877.

Aaberg Jr TM, Flynn Jr HW, Schiffman J, Newton J . Nosocomial acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis survey. A 10-year review of incidence and outcomes. Ophthalmology 1998; 105 (6): 1004–1010.

Desai P, Minassian D.C, Reidy A . National cataract surgery survey 1997–1998: a report of the results of the clinical outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 1336–1340.

Foot B, Stanford M, Rahi J, Thompson J . The British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit: an evaluation of the first 3 years. Eye 2003; 17: 9–15.

Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Arch Ophthalmol 1995; 113: 1479–1496.

Thacker SB, Redmond S, Berkelman RL . A controlled trial of disease surveillance strategies. Am J Prev Med 1986; 2: 345–350.

Vogt RL, LaRue D, Klaucke DN, Jillison DA . Comparison of an active and passive surveillance system of primary care providers for hepatitis, measles, rubella and salmonellosis in Vermont. Am J Public Health 1983; 73: 795–797.

Foot BG, Stanford MR . Questioning Questionnaires. Eye 2001; 15: 693–694.

Hughes DS, Hill RJ . Infectious endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 1994; 78 (3): 227–232.

Olson JC, Flynn Jr HW, Forster RK, Culbertson WW . Results in the treatment of postoperative endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology 1983; 90 (6): 692–699.

Okhravi N, Adamson P, Matheson MM, Towler HM, Lightman S . PCR-RFLP-mediated detection and speciation of bacterial species causing endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000; 41 (6): 1438–1447.

Hykin PG, Tobal K, McIntyre G, Matheson MM, Towler HM, Lightman SL . The diagnosis of delayed post-operative endophthalmitis by polymerase chain reaction of bacterial DNA in vitreous samples. J Med Microbiol 1994; 40 (6): 408–415.

Therese KL, Anand AR, Madhavan HN . Polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of bacterial endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82 (9): 1078–1082.

Barza M, Pavan PR, Doft BH, Wisniewski SR, Wilson LA, Han DP et al. Evaluation of microbiological diagnostic techniques in postoperative endophthalmitis in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115 (9): 1142–1150.

Peyman GA . Antibiotic administration in the treatment of bacterial endophthalmitis. II. Intravitreal injections. Surv Ophthalmol 1977; 21 (4): 332, 339–346.

Davidson SI . Post-operative bacterial endophthalmitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1985; 104 (Part 3): 278–284.

Okhravi N, Towler HM, Hykin P, Matheson M, Lightman S . Assessment of a standard treatment protocol on visual outcome following presumed bacterial endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1997; 81 (9): 719–725.

Murray DC, Christopoulou D, Hero M . Intravitreal penetration of teicoplanin (letter; comment). Eye 1999; 13 (Part 4): 604–605.

Campochiaro PA, Conway BP . Aminoglycoside toxicity—a survey of retinal specialists. Implications for ocular use (see comments). Arch Ophthalmol 1991; 109 (7): 946–950.

Park SS, Vallar RV, Hong CH, von Gunten S, Ruoff K, D’Amico DJ . Intravitreal dexamethasone effect on intravitreal vancomycin elimination in endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117 (8): 1058–1062.

Shah GK, Stein JD, Sharma S, Sivalingam A, Benson WE, Regillo CD et al. Visual outcomes following the use of intravitreal steroids in the treatment of postoperative endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology 2000; 107 (3): 486–489.

Harris MJ . Visual outcome after intravitreal steroid use for postoperative endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology 2001; 108 (2): 240–241.

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Guidance for Clinical Governance in Ophthalmology. 8. 1999. Ref Type: Report.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the support of the British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit.

We thank Mr MD Cole, Torbay Hospital and Professor S Lightman, Institute of Ophthalmology, London for providing helpful advice.

This work was supported by the British Medical Association Middlemore and John William Clarke awards, for which we are grateful.

We particularly thank the following Ophthalmologists for helping with the data collection for our study: Mr SP Aggarwal, Mr BDS Allan, Mr ED Allen, Mr N Anand, Mr S Armstrong, Mr MW Austin, Mr PJ Bacon, Dr T Barrie, Mr R Bates, Mr AK Bates, Mr JDL Beare, Mr MA Bearn, Mrs L Beck, Mr B Beigi, Dr GJB Bedford, Dr RWD Bell, Mr PD Black, Mr RC Bosanquet, Mr DC Broadway, Mr RL Burton, Miss ZA Butt, Mr AB Callear, Mr SH Campbell, Mr C Canning, Mr AG Casswell, Miss M Chatterjee, Mr SK Choudhuri, Mr M Clowes, Mr SD Cook, Miss M Corbett, Mr PG Corridan, Mr EA Craig, Mr JKG Dart, Mr RB Dapling, Mr D David, Mr C Dees, Mr SP Desai, Mr J Deutsch, Mr D Dhingra, Mr CJM Diaper, Professor A Dick, Mr RS Edwards, Mr M Ekstein, Mr IR Fearnley, Dr AI Fern, Mr TJ Fetherston, Miss L Ficker, Mr FF Fisher, Mr Fouladi, Miss W Franks, Mr LB Freeman, Mr TJ Freegard, Dr MP Gavin, Mr PTS Gregory, Mr BP Greaves, Mr AK Gupta, Mr M Harris, Mr AA Hashim, Mr S Hardman Lea, Mr W Hoe, Mr IH Hubbard, Mr RC Humphry, Mr DS Hughes, Mr JR Innes, Mr DV Inglesby, Mr B James, Mr JSH Jacob, Mr D Jones, Mr PW Joyce, Mr J Keast-Butler, Mr MG Kerr-Muir, Mr T Leslie, Mr SG Levy, Mr J Lipton, Mr CSC Liu, Mr D Lloyd-Jones, Miss AL Lyness, Mr TD Manners, Dr CJ MacEwen, Professor D Mcleod, Mr JN McGalliard, Mr JMS McConnell, Dr Moosavi, Mr AT Moore, Mr SJ Morgan, Mrs CE Morton, Mr A Murray, Professor PI Murray, Dr SB Murray, Dr RI Murray, Mr ME Nelson, Mr BJ McNeela, Mr NP O’Donnell, Mr G O’Connor, Mr CO Peckar, Mr RV Pearson, Mr RP Phillips, Mr P Phelan, Mr W Pollock, Mr K Potu, Mr S Rassam, Professor IG Rennie, Mr RM Redmond, Mr T Rimmer, Mr PH Rosen, Mr J Shah, Mr D Steele, Dr IG Syme, Mr C Stevenson, Mr RJ Stirling, Mr P Sullivan, Miss HC Seward, Mr JH Sandford-Smith, Mr KP Stannard, Mr G Sturrock, Mr T Shetti, Miss SN Stefanous, Mr SJ Talks, Mr V Thaller, Mr GM Thompson, Mr NMG Toma, Mr S Tuft, Mr AB Tullo, Mr AG Tyers, Mr S Verghese, Mr AJ Vivian, Miss A Walker, Mr J Wallace, Mr RF Walters, Mr JNF West, Ms S Weber, Dr IF White, Mr ACA While, Mr WH Woon, Mr R Wormald.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kamalarajah, S., Silvestri, G., Sharma, N. et al. Surveillance of endophthalmitis following cataract surgery in the UK. Eye 18, 580–587 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700645

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700645