Abstract

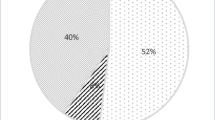

Over half of all workers in the developing world are self-employed. Although some self-employment is chosen by entrepreneurs with well-defined projects and ambitions, roughly two-thirds results from individuals having no better alternatives. The importance of self-employment in the overall distribution of jobs is determined by many factors, including social protection systems, labor market frictions, the business environment and labor market institutions. However, self-employment in the developing world tends to be low-productivity employment, and as countries move up the development path, the availability of wage employment grows and the mix of jobs changes.

Abstract

Plus de la moitié de la population active dans les pays en développement travaille à son compte. Bien que travailler à son compte est l’option que choisissent les entrepreneurs indépendants ayant des projets et des ambitions bien définis, environ deux tiers des individus choisissent cette voie par manque d’alternative. L’importance de l’emploi indépendant dans la distribution totale des postes est déterminée par de nombreux facteurs, y compris les systèmes de protection sociale, les tensions sur le marché du travail, l’environnement commercial, et les institutions du marché du travail. Cependant, l’emploi indépendant dans les pays en développement a tendance à regrouper des activités à basse productivité, et au fur et à mesure que les pays se développent, la disponibilité de l’emploi salarié augmente et le mélange des postes change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Desai (2009) for a discussion of some of these issues.

Contributing family workers are defined as people ‘…who hold self-employment jobs in an establishment operated by a related person, with a too limited degree of involvement in its operation to be considered a partner’.

See Bergmann et al (forthcoming) for a specific discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of the GEM data for academic research. Relative to other individual databases, some of its primary disadvantages relate to sample size, sampling strategies and transferability of the developed country questionnaire to the developing country context.

See Tybout (2000). More recently, Sandefur (2010) shows that 85 per cent of manufacturing firms in Ghana in 2003 had fewer than 10 employees per establishment.

Dillon et al (2012) show, for example, that proxy response does not generate significant errors in the much more sensitive case of child labor reports in Tanzania.

See Weber and Denk (2011) for a detailed discussion of imputation techniques for labor market data.

Mauritius and South Africa were the only two countries in the SSA region that produced data for LABORSTA every year between 2000 and 2008.

It is important to note that the I2D2 sample used by Gindling and Newhouse (2012) covers an estimated 63 per cent of the population of low- and middle-income countries, and 60 per cent of all countries worldwide. The main loss of worldwide population comes from the lack of data on China (coverage of East Asian and Pacific developing countries is only 21 per cent) and some larger Middle Eastern and North African countries, such as Algeria, Iran, Iraq and Lebanon (regional coverage among MENA developing countries is 46 per cent).

TEA is defined (Xavier et al (2013), p. 13) as the sum of nascent entrepreneurs (those starting new enterprises less than three months old) and new business owners (former nascent entrepreneurs who have been in business for more than three months, but less than three and a half years).

Established businesses are those that have been in existence for more than three and a half years (Xavier et al (2013), p.13).

Most surveys in the GEM data use telephone interviewing, which will tend to under-sample poor households who cannot afford telephones and may be more likely to be subsistence entrepreneurs.

The Gindling and Newhouse (2012) results weight the averages by population (larger countries get more weight), while Xavier et al (2013) equally weight countries in their tables.

See, for example, Fields (2012) or Poschke (2013a) for the ‘necessity’ perspective and some of the work of David McKenzie and co-authors (such as de Mel et al (2008)) for the ‘opportunity’ perspective. Perry et al (2007) presents both sides in a study on Latin America, while Bosch and Maloney (2010) present an empirical analysis of transitions into and out of self-employment.

Schoar (2010) uses an alternative distinction between subsistence and transformational entrepreneurs, but her categories often resemble those found elsewhere in the literature. Papers such as de Mel et al (2010a) address this distinction directly.

Poschke (2013b, 2013c) and Margolis and Robalino (2013) present decision-theoretic frameworks for modeling entry into self-employment, and subsequent success, in the developing world.

See the World Bank’s ASPIRE database for details (datatopics.worldbank.org/aspire/).

See, for example, the IFS-World Bank Doing Business database (doingbusiness.org) or the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s National Expert Surveys (www.gemconsortium.org).

Djankov et al (2007) examine constraints to accessing capital in 129 countries.

See de Mel et al (2008, 2012a) and McKenzie and Woodruff (2006). See Karlan et al (2012) for an explanation as to why high returns on capital may not be more frequently observed.

See Djankov et al (2002). Djankov (2008) provides a more recent survey of the literature linking regulations to entry in developing countries.

See Bruhn (2011) for the case of a reform of business registration procedures in Mexico.

See de Mel et al (2012b) for an experiment that provided information and lowered the cost of formalization in Sri Lanka.

Kaplan et al (2007) and Kaplan and Sadka (2011) provide evidence on the effectiveness of the legal system for resolving disputes in Mexico.

See Djankov and Ramalho (2009) for an overview.

See Margolis (2014) for a discussion of the implementation of minimum wages in the developing world and Gindling (2014) for an overview of their effects.

For a recent assessment, see Charmes (2012).

Betcherman et al (2004) survey the impact of employment programs, including wage subsidies, in developing countries and conclude that the impact is limited, at best, yet imply important deadweight losses and substitution costs.

See Bögenhold et al (2013) for a different perspective on this distinction.

The issue of measurement of entrepreneurship relative to self-employment in the developed world has been addressed by Bjuggren et al (2010).

Random House Dictionary (dictionary.reference.com/browse/entrepreneur?s=t).

Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition (dictionary.reference.com/browse/entrepreneur?s=t).

Schoar’s (2010) definition of ‘transformational’ entrepreneurship corresponds more closely to this distinction, although one might further disaggregate her categories into truly transformational entrepreneurs (with revolutionary ideas and high growth potential) and more traditional, vocational entrepreneurs.

Xavier et al (2013) present somewhat counterintuitive results drawn from these data, such as higher necessity-driven TEA in non-EU Europe, where formal social protection systems exist, than in any other region, including Sub-Saharan Africa, where they are often inadequate or entirely absent. These results may be driven by sampling issues, but suggest that the variables should be used with caution.

See Gries and Naudé (2010) for a model along these lines.

This mechanism is a common feature of endogenous growth models; see the October 1990 issue of the Journal of Political Economy for a series of papers all adopting a similar framework.

Development processes such as those described in Figure 4 have been modeled extensively in the macroeconomic dynamics literature (see, for example, Alvarez-Cuadrado and Poschke, 2011; Gollin et al, 2002, 2004; McMillan and Rodrik, 2011).

References

Almeida, R.K. and Carneiro, P. (2011) Enforcement of Labor Regulation and Informality. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA Discussion Papers no. 5902.

Alvarez-Cuadrado, F. and Poschke, M. (2011) Structural change out of agriculture: Labor push versus labor pull. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3 (3): 127–158.

Baliamoune-Lutz, M., Brixiova, Z. and Ndikumana, L. (2011) Credit Constraints and Productive Entrepreneurship in Africa. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA Discussion Papers no. 6193.

Bergmann, H., Mueller, S. and Schrettle, T. (forthcoming) The use of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor data in academic research: A critical inventory and future potentials. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing.

Betcherman, G., Olivas, K. and Dar, A. (2004) Impacts of active labor market programs: New evidence from evaluations with particular attention to developing and transition countries. Washington DC: World Bank, World Bank Social Protection Discussion Paper no. 29142.

Bjuggren, C.M., Johansson, D. and Stenkula, M. (2010) Using Self-employment as Proxy for Entrepreneurship: Some Empirical Caveats. Stockholm, Sweden: Research Institute of Industrial Economics, Research Institute of Industrial Economics Working Paper no. 845.

Bloom, N., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D. and Roberts, J. (2010) Why do firms in developing countries have low productivity? American Economic Review 100 (2): 619–623.

Bögenhold, D., Heinonen, J. and Akola, E. (2013) Entrepreneurship and Independent Professionals: Why do Professionals not meet with Stereotypes of Entrepreneurship? Klagenfurt, Austria: Institut für Soziologie, Alpen-Adria-Universität, MPRA Working Paper no. 51529.

Bosch, M. and Maloney, W.F. (2010) Comparative analysis of labor market dynamics using Markov processes: An application to informality. Labour Economics 17: 621–631.

Brown, J.D., Earle, J.S. and Lup, D. (2004) What Makes Small Firms Grow? Finance, Human Capital, Technical Assistance, and the Business Environment in Romania. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA Discussion Papers no. 1343.

Bruhn, M. (2011) License to sell: The effect of business registration reform on entrepreneurial activity in Mexico. The Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (1): 382–386.

Campos, N.F., Dimova, R. and Saleh, A. (2010a) Whither Corruption? A Quantitative Survey of the Literature on Corruption and Growth. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA Discussion Papers no. 5334.

Campos, N.F., Estrin, S. and Proto, E. (2010b) Corruption as a Barrier to Entry: Theory and Evidence. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA Discussion Papers no. 5243.

Charmes, J. (2012) The informal economy worldwide: Trends and characteristics. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research 6 (2): 103–132.

Cho, Y., Margolis, D.N. and Robalino, D.A. (2012) Labor Markets in Low and Middle Income Countries: Trends and Implications for Social Protection and Labor Policies. Washington DC: World Bank, World Bank Social Protection Discussion Papers no. 67613.

Chuhan-Pole, P., Angwafo, M., Buitano, M., Dennis, A., Korman, V. and Fox, M.L. (2011) Africa Pulse: An Analysis of Issues Shaping Africa’s Economic Future. Vol. 4. Washington DC: The World Bank.

de Mel, S., McKenzie, D. and Woodruff, C. (2008) Returns to capital in microenterprises: Evidence from a field experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (4): 1329–1372.

de Mel, S., McKenzie, D. and Woodruff, C. (2010a) Who are the microenterprise owners? Evidence from Sri Lanka on Tokman versus De Soto. In: J. Lerner and A. Schoar (eds.) International Differences in Entrepreneurship. Cambridge, MA, National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 63–87.

de Mel, S., McKenzie, D. and Woodruff, C. (2010b) Wage subsidies for microenterprises. American Economic Review 100 (2): 614–618.

de Mel, S., McKenzie, D. and Woodruff, C. (2012a) One-Time transfers of cash or capital have long-lasting effects on microenterprises in Sri Lanka. Science 335 (6071): 962–966.

de Mel, S., McKenzie, D. and Woodruff, C. (2012b) The Demand for, and Consequences of, Formalization among Informal Firms in Sri Lanka. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA Discussion Papers no. 6442.

Desai, S. (2009) Measuring Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries. Helsinki, Finland: World Institute for Development Economics Research, United Nations University, UNU-WIDER Research Paper no. 2009/10.

De Soto, H. (1989) The Other Path. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

Dillon, A., Bardasi, E., Beegle, K. and Serneels, P. (2012) Explaining variation in child labor statistics. Journal of Development Economics 98 (1): 136–147.

Djankov, S. (2008) The Regulation of Entry: A Survey. London, UK: CEPR, CEPR Discussion Papers no. 7080.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F. and Shleifer, A. (2002) The regulation of entry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (1): 1–37.

Djankov, S., McLiesh, C. and Shleifer, A. (2007) Private credit in 129 countries. Journal of Financial Economics 84 (2): 299–329.

Djankov, S., Ganser, T., McLiesh, C., Ramalho, R. and Shleifer, A. (2010) The effect of corporate taxes on investment and entrepreneurship. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2 (3): 31–64.

Djankov, S. and Ramalho, R. (2009) Employment laws in developing countries. Journal of Comparative Economics 37 (1): 3–13.

Fields, G.S. (2012) Working Hard, Working Poor: A Global Journey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gindling, T.H. (2014) Minimum Wages and Poverty in Developing Countries. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA World of Labor.

Gindling, T.H. and Newhouse, D. (2012) Self-employment in the developing world. Washington DC: World Bank, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 6201.

Gollin, D., Parente, S. and Rogerson, R. (2002) The role of agriculture in development. American Economic Review 92 (2): 160–164.

Gollin, D., Parente, S.L. and Rogerson, R. (2004) Farm work, home work, and international productivity differences. Review of Economic Dynamics 7 (4): 827–850.

Gries, T. and Naudé, W. (2010) Entrepreneurship and structural economic transformation. Small Business Economics 34 (1): 13–29.

Grimm, M., Knorringa, P. and Lay, J. (2012) Constrained gazelles: High potentials in West Africa’s informal economy. World Development 40 (7): 1352–1368.

Kaplan, D.S. and Sadka, J. (2011) The Plaintiff’s Role in Enforcing a Court Ruling: Evidence from a Labor Court in Mexico. Washington DC: Interamerican development Bank, IDB Publications, no. 38198.

Kaplan, D.S., Sadka, J. and Silva-Mendez, J.L. (2007) Litigation and Settlement: New Evidence from Labor Courts in Mexico. Washington DC: World Bank, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 4434.

Karlan, D., Knight, R. and Udry, C. (2012) Hoping to Win, Expected to Lose: Theory and Lessons on Micro Enterprise Development. Cambridge, MA: NBER, NBER Working Papers no. 18325.

Margolis, D.N. (2014) Positive and Negative Implications of Introducing Minimum Wages in Middle and Low Income Countries. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA World of Labor.

Margolis, D.N., Newhouse, D. and Weber, M. (2010a) Employment changes and the crisis: What happened in data-poor countries? Presented at 5th IZA/World Bank Conference: Employment and Development, Cape Town, South Africa.

Margolis, D.N., Newhouse, D. and Weber, M. (2010b) Improving Policy Making through Better Data. Washington DC: The World Bank (mimeo).

Margolis, D.N. and Robalino, D.A. (2013) Skills, Self-Employment and Entrepreneurial Success. Paris, France: Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne (mimeo).

McKenzie, D.J. and Woodruff, C. (2006) Do entry costs provide an empirical basis for poverty traps? Evidence from Mexican microenterprises. Economic Development and Cultural Change 55 (1): 3–42.

McMillan, M.S. and Rodrik, D. (2011) Globalization, Structural Change and Productivity Growth. Cambridge, MA: NBER, NBER Working Papers no. 17143.

Meyer, B.D. (1990) Unemployment insurance and unemployment spells,. Econometrica 58 (4): 757–82.

Perry, G., Maloney, W., Arias, O., Fajnzylber, P., Mason, A. and Saavedra-Chanduvi, J. (2007) Informality: Exit and Exclusion. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Poschke, M. (2013a) ‘Entrepreneurs out of necessity’: A snapshot. Applied Economics Letters 20 (7): 658–663.

Poschke, M. (2013b) The Decision to Become an Entrepreneur and the Firm Size Distribution: A Unifying Framework for Policy Analysis. Bonn, Germany: IZA, IZA Discussion Papers no. 7757.

Poschke, M. (2013c) Who becomes an entrepreneur? Labor market prospects and occupational choice. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 37 (3): 693–710.

Sandefur, J. (2010) On the Evolution of the Firm Size Distribution in an African Economy, Oxford, UK: Center for the Study of African Economies. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford, CSAE Working Paper Series, no. 2010-05.

Schoar, A. (2010) The divide between subsistence and transformational entrepreneurship. In: J. Lerner and S. Scott (eds.) Innovation Policy and the Economy. Vol. 10 Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 57–81.

Tokman, V.E. (2007) Modernizing the informal sector. New York, NY: United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Working Papers no. 42.

Tybout, J.R. (2000) Manufacturing firms in developing countries: How well do they do, and why? Journal of Economic Literature 38 (1): 11–44.

Weber, M. and Denk, M. (2011) Avoid Filling Swiss Cheese with Whipped Cream: Imputation Techniques and Evaluation Procedures for Cross-Country Time Series. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund, International Monetary Fund Working Paper no. WP/11/151.

World Bank (2012) World Development Report 2013: Jobs. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Xavier, S.R., Kelley, D., Kew, J., Herrington, M. and Vorderwülbecke, A. (2013) Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2012 Global Report, Babson College (Babson Park, MA), Universidad del Desarrollo (Saltiago, Chile) and the Universiti Tun Abdul Razak (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) and housed in the London Business School, London, UK. http://www.gemconsortium.org/docs/download/2645.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Margolis, D. By Choice and by Necessity: Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment in the Developing World. Eur J Dev Res 26, 419–436 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.25

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.25