-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Francesca M. Bosco, Francesca Capozzi, Livia Colle, Paolo Marostica, Maurizio Tirassa, Theory of Mind Deficit in Subjects with Alcohol Use Disorder: An Analysis of Mindreading Processes, Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 49, Issue 3, May/June 2014, Pages 299–307, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agt148

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Aim: The aim of the study was to investigate multidimensional Theory of Mind (ToM) abilities in subjects with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Method: A semi-structured interview and a set of brief stories were used to investigate different components of the participants' ToM, namely first- vs. third-person, egocentric vs. allocentric, first- vs. second-order ToM in 22 persons with AUD plus an equal number of healthy controls. Participants were administered the Theory of Mind Assessment Scale (Th.o.m.a.s., Bosco et al., 2009a) and the Strange Stories test ( Happé et al., 1999). Results: Persons with AUD performed worse than controls at all ToM dimensions. The patterns of differences between groups varied according to the Th.o.m.a.s. dimension investigated. In particular persons with AUD performed worse at third-person than at first-person ToM, and at the allocentric than at the egocentric perspective. Conclusion: These findings support the hypothesis that the ability to understand and ascribe mental states is impaired in AUD. Future studies should focus on the relevance of the different ToM impairments as predictors of treatment outcome in alcoholism, and on the possibility that rehabilitative interventions may be diversified according to ToM assessment.

INTRODUCTION

Theory of Mind (ToM)—or ‘Mindreading’—was originally defined by Premack and Woodruff (1978) as the ability to ascribe mental states to oneself and to others and to use this knowledge to predict and explain actions and behaviours.

Studies on social cognition in alcoholism have shown that the chronic abuse of alcohol (i.e. alcoholism) is associated with impairments in the ability to recognize and decode Emotional Facial Expression (EFE) (Philipot et al., 1999; Kornreich et al., 2002; Townshed and Duka, 2003; Uekermann et al., 2005; Foisy et al., 2007; Maurage et al., 2009, 2011a), in emotional prosody and body postures (Uekermann et al., 2005), in ‘emotional empathy’, i.e. the ability to detect and experience other people's emotional states (Maurage et al., 2011b; Gizewski et al., 2012) and, generally speaking, in social cognition (for a review see Uekermann and Daum, 2008).

At the best of our knowledge, only one study focused on ToM in subjects with alcohol use disorder (henceforth AUD), finding that it was impaired (Uekermann et al., 2007; Gizewski et al., 2012). While investigating humour processing in AUD, Uekermann and colleagues found cognitive as well as affective deficits in how AUD subjects processed humour, when compared with control subjects (henceforth CS). The impairments observed were related in particular to ToM (lower scores by AUD subjects on three mentalistic questions about the characters in a set of jokes) and executive functions (working memory).

Considering the paucity of empirical research on this topic, we decided to assess ToM abilities in a sample of persons with AUD.

ToM has a complex nature and cannot be reduced to an on–off or an all-or-nothing functioning (Mazza et al., 2001; Vogeley et al., 2001; Nichols and Stich, 2002; Saxe et al., 2006; Bosco et al., 2009a,b;). A first and well-known distinction in the literature is between first- and second-order ToM. First-order ToM reasoning requires understanding a character's beliefs about a state of the world, while success in second-order tasks requires understanding nested mental states, that is understanding a character's beliefs about the beliefs of another character. Of course, this turns out to be more difficult. Empirical studies showed that both in children (Wimmer and Perner, 1983) and in a clinical sample of persons with schizophrenia—a psychiatric pathology which is also characterized by ToM impairment (Frith, 1992)—second-order ToM tasks are more difficult than first-order ones (Mazza et al., 2001).

A second important distinction is that between first-person ToM, i.e. knowledge about one's own mental states, and third-person ToM, i.e. the ability to understand the mental states of others (Vogeley et al., 2001; Nichols and Stich, 2003). Initial empirical evidence suggests that a clinical sample of patients with schizophrenia found it easier to reason in the first than in the third person (Bosco et al., 2009a). However, classical empirical tasks built to investigate ToM ability focus solely on third-person ToM (Wimmer and Perner, 1983; Happé et al., 1999).

Another distinction, orthogonal to that between first and third-person ToM, is between egocentrism and allocentrism (Frith and De Vignemont, 2005). In the egocentric perspective, the others are represented in relation to the self, while in the allocentric perspective their mental states are represented independently from the self.

Finally, the scope of ToM includes different kind of mental states: emotions (Harris, 1994), desires (Wellman, 1990) and beliefs (Wimmer and Perner, 1983) are the most important types of mental states that a person is able to comprehend (Tirassa, 1999; Tirassa et al., 2006a,b; Tirassa and Bosco, 2008), apart of course from sheer intentions, and those that are most often investigated in the literature.

In the light of these considerations, the aim of the present study was to conduct a broad assessment of ToM abilities in subjects with AUD. To fulfil this goal we used (as described in detail in the next section) the Th.o.m.a.s (Bosco et al., 2009a; see also Castellino et al., 2011; Laghi et al. in press), a semi-structured interview for investigating various aspects of ToM, plus a classical ToM test (Strange Stories test, Happé et al., 1999).

In line with the results of Uekermann et al. (2007) we expected that:

Persons with AUD would present an impaired ToM when compared with controls. More specifically, in line with the literature showing that ToM is a complex activity (Bosco et al. 2009a,b) we expected that:

Persons with AUD would present an impaired ToM when compared with controls on each specific ToM dimension, namely first- and third-person ToM, egocentric and allocentric perspective, first- and second-order ToM.

Furthermore we expected that such deficit would affect the comprehension of and reasoning upon different kind of mental states, namely emotions, desires and beliefs. Also, in the light of studies (Mazza et al., 2001; Bosco et al., 2009a) to the effect that the deficit of mindreading in patients with schizophrenia affects certain components of ToM more heavily than others, we expected in AUD, but not in control subjects, that:

Second-order ToM would be more difficult than first-order ToM;

Third-person ToM would be more difficult than first-person ToM;

Finally, for explorative purposes we also investigated whether differences existed in AUD (but not in CS) between tasks requiring an allocentric vs. egocentric perspective and between different kinds of mental states, namely desires, beliefs and emotions.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-two persons (15 men and 7 women; age: mean = 49.64 ± 8.08 years; years of formal education: mean = 11.77 ± 4.14) with a history of chronic abuse of alcohol plus an equal number of healthy control subjects (CS) (15 males, 7 females, age: mean = 49.32 ± 8.17 years; years of formal education: mean = 12.05 ± 4.24) helped us gather the present data (all the statistics are reported with ±SD). The diagnosis of AUD was made by a psychologist or a psychiatrist, not involved in the research and independently of it, based on DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994).

The length of alcohol abuse ranged from 36 to 480 months (mean = 137.24 ± 128.43); the age of onset of alcohol abuse ranged from 17 to 60 years (mean = 35.8 ± 11.76). All participants were in treatment at Aliseo, an association in Turin that offers help and support to people with alcohol dependence; the association had been providing support for 2–51 months (mean = 15.89 ± 14.13). All participants were native speakers of Italian. All were adults and abstinent from alcohol at the time of the interview; the length of abstinence ranged from 1 to 84 months (mean = 10.56 ± 17.74). All but one of the subjects were receiving medications: 13 were specifically treated for alcohol dependence with disulfiram, 4 were receiving anxiolytics, 2 antidepressants and 1 both antidepressants and disulfiram. The dose of anxiolytics and antidepressants ranged from light to moderate. There was no record of side effects due to the usage of disulfiram. More detail about each participant's duration of abuse, abstinence, support, and drug administration is provided in Table 1.

Data of all the participants (AUD) in relation to the duration of therapy at Aliseo association, the duration of abuse, the duration of abstinence and the medication received.

| ID subject . | Therapy . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . | Pharmacological medications . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfiram . | Anxiolytics . | Antidepressants . | ||||

| S1 | 4.00 | 3.0 | 72.0 | ✓ | ||

| S2 | 2.00 | 1.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S3 | 12.00 | 7.0 | 42.0 | ✓ | ||

| S4 | 12.00 | 12.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S5 | 36.00 | 1.5 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S6 | 12.00 | 1.0 | 55.2 | ✓ | ||

| S7 | 48.00 | 24.0 | 120.0 | |||

| S8 | 10.00 | 1.5 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S9 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 60.0 | |||

| S10 | 18.00 | 6.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S11 | 12.00 | 10.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S12 | 12.00 | 2.0 | 54.0 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| S13 | 24.00 | 12.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S14 | 3.00 | 1.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S15 | 19.00 | 3.0 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S16 | 33.00 | 24.0 | 48.0 | ✓ | ||

| S17 | 51.00 | 84.0 | 360.0 | ✓ | ||

| S18 | 11.00 | 12.0 | 240.0 | ✓ | ||

| S19 | 8.00 | 5.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S20 | 10.00 | 3.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S21 | 4.00 | 5.5 | 420.0 | ✓ | ||

| S22 | 6.00 | 12.0 | 480.0 | ✓ | ||

| ID subject . | Therapy . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . | Pharmacological medications . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfiram . | Anxiolytics . | Antidepressants . | ||||

| S1 | 4.00 | 3.0 | 72.0 | ✓ | ||

| S2 | 2.00 | 1.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S3 | 12.00 | 7.0 | 42.0 | ✓ | ||

| S4 | 12.00 | 12.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S5 | 36.00 | 1.5 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S6 | 12.00 | 1.0 | 55.2 | ✓ | ||

| S7 | 48.00 | 24.0 | 120.0 | |||

| S8 | 10.00 | 1.5 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S9 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 60.0 | |||

| S10 | 18.00 | 6.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S11 | 12.00 | 10.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S12 | 12.00 | 2.0 | 54.0 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| S13 | 24.00 | 12.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S14 | 3.00 | 1.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S15 | 19.00 | 3.0 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S16 | 33.00 | 24.0 | 48.0 | ✓ | ||

| S17 | 51.00 | 84.0 | 360.0 | ✓ | ||

| S18 | 11.00 | 12.0 | 240.0 | ✓ | ||

| S19 | 8.00 | 5.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S20 | 10.00 | 3.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S21 | 4.00 | 5.5 | 420.0 | ✓ | ||

| S22 | 6.00 | 12.0 | 480.0 | ✓ | ||

Durations are in months.The ✓ indicates the patients' assumption of the corresponding medication.

Data of all the participants (AUD) in relation to the duration of therapy at Aliseo association, the duration of abuse, the duration of abstinence and the medication received.

| ID subject . | Therapy . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . | Pharmacological medications . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfiram . | Anxiolytics . | Antidepressants . | ||||

| S1 | 4.00 | 3.0 | 72.0 | ✓ | ||

| S2 | 2.00 | 1.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S3 | 12.00 | 7.0 | 42.0 | ✓ | ||

| S4 | 12.00 | 12.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S5 | 36.00 | 1.5 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S6 | 12.00 | 1.0 | 55.2 | ✓ | ||

| S7 | 48.00 | 24.0 | 120.0 | |||

| S8 | 10.00 | 1.5 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S9 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 60.0 | |||

| S10 | 18.00 | 6.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S11 | 12.00 | 10.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S12 | 12.00 | 2.0 | 54.0 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| S13 | 24.00 | 12.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S14 | 3.00 | 1.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S15 | 19.00 | 3.0 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S16 | 33.00 | 24.0 | 48.0 | ✓ | ||

| S17 | 51.00 | 84.0 | 360.0 | ✓ | ||

| S18 | 11.00 | 12.0 | 240.0 | ✓ | ||

| S19 | 8.00 | 5.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S20 | 10.00 | 3.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S21 | 4.00 | 5.5 | 420.0 | ✓ | ||

| S22 | 6.00 | 12.0 | 480.0 | ✓ | ||

| ID subject . | Therapy . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . | Pharmacological medications . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfiram . | Anxiolytics . | Antidepressants . | ||||

| S1 | 4.00 | 3.0 | 72.0 | ✓ | ||

| S2 | 2.00 | 1.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S3 | 12.00 | 7.0 | 42.0 | ✓ | ||

| S4 | 12.00 | 12.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S5 | 36.00 | 1.5 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S6 | 12.00 | 1.0 | 55.2 | ✓ | ||

| S7 | 48.00 | 24.0 | 120.0 | |||

| S8 | 10.00 | 1.5 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S9 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 60.0 | |||

| S10 | 18.00 | 6.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S11 | 12.00 | 10.0 | 60.0 | ✓ | ||

| S12 | 12.00 | 2.0 | 54.0 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| S13 | 24.00 | 12.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S14 | 3.00 | 1.5 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S15 | 19.00 | 3.0 | 180.0 | ✓ | ||

| S16 | 33.00 | 24.0 | 48.0 | ✓ | ||

| S17 | 51.00 | 84.0 | 360.0 | ✓ | ||

| S18 | 11.00 | 12.0 | 240.0 | ✓ | ||

| S19 | 8.00 | 5.0 | 120.0 | ✓ | ||

| S20 | 10.00 | 3.0 | 36.0 | ✓ | ||

| S21 | 4.00 | 5.5 | 420.0 | ✓ | ||

| S22 | 6.00 | 12.0 | 480.0 | ✓ | ||

Durations are in months.The ✓ indicates the patients' assumption of the corresponding medication.

Inclusion criteria for subjects with AUD were a score >III on Raven's Progressive Matrices, which may be considered acceptable according to Raven's criteria (Raven, 1939), and at least 1 month of abstinence. The exclusion criterion was a diagnosis of Korsakoff's syndrome.

Exclusion criteria for both subjects with AUD and controls included an anamnesis of psychiatric, neurological or neuropsychological disease, leucotomy, head injury and other substance abuse (defined as per DSM-IV, APA, 1994).

Materials and procedure

One of the authors or a research assistant administered the experimental material individually to each participant. The administration took place in a quiet room: AUD patients were tested at Aliseo Centre (the facility where they were treated; the controls were tested at home). The administration required one or two sessions, a total duration of ∼90 min.

Theory of Mind Assessment Scale

The Theory of Mind Assessment Scale (Th.o.m.a.s., Bosco et al., 2009a) is a semi-structured interview using a unitary methodology to investigate the various aspects of ToM abilities and to delineate a comprehensive profile thereof (see Appendix A). Th.o.m.a.s. consists of 39 open-ended questions that leave the interviewee free to express and articulate his/her thoughts; the questions are organized along four scales, each focusing on one of the knowledge domains in which a person's ToM may be manifested.

Scale A, I–Me. This investigates the interviewee's knowledge (I) of her own mental states (Me). This scale investigates first-person ToM.

Scale B, Other–Self. This investigates the knowledge that, according to the interviewee, other persons (Other) have of their own mental states (Self), independently of the subject's own position. This scale investigates third-person ToM from an egocentric perspective.

Scale C, I–Other. This investigates the interviewee's (I) knowledge of the mental states of other persons (Other). Like scale B, also scale C investigates third-person ToM, but from an allocentric perspective.

Scale D, Other–Me. This investigates the knowledge that, from the interviewee's point of view, others (Other) have of her mental states (Me). This scale can be compared with a second-order ToM task, in that the abstract form of the questions is: ‘What do you think that others think that you think?’.

Each scale is divided into three subscales that respectively explore the dimensions of Awareness, i.e. the interviewee's ability to perceive and differentiate beliefs, desires and emotions in herself and in others, Relation, i.e. the interviewee's ability to recognize causal relations between different mental states and between them and the resulting behaviours, and Realization, i.e. the interviewee's ability to adopt effective strategies aimed at affecting her own mental states and behaviour as well as those of the others. Each scale evaluates the interviewee's perspectives on epistemic states (knowledge, beliefs and so on), volitional states (desires, intentions and so on) and positive and negative emotions.

With the consent of the interviewees, Th.o.m.a.s. interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. Transcriptions were rated by two independent judges: these were two assistant researchers who had not taken part in the interviewing phase and were blind to the experimental hypotheses as well as to whether they were coding responses from the experimental or the control group. Judges assigned each answer a score from 0 to 4, according to the given rating criteria. For a description of the rating criteria see Appendix B (see also Bosco et al., 2009a).

Judges reached a significant level of inter-reliability on their first judgments of performance at Th.o.m.a.s both for AUD (correlation coefficient: 6.86 < Z < 10.37; 0.0001 < P < 0.001) and CS (correlation coefficient: 2.37 < Z < 7.05; 0.02 < P < 0.0001). They then discussed each item upon which they disagreed in order to reach a full agreement and assign the final score.

Strange stories

In the Strange Stories test (Happé et al., 1999), we presented a selection of six Strange Stories, excluding those that require the comprehension of communicative acts such as metaphors and irony. An example: ‘A burglar who has just robbed a shop is making his getaway. As he is running home, a policeman on his beat sees him drop his glove. He does not know the man is a burglar; he just wants to tell him he dropped his glove. But when the policeman shouts out to the burglar, “Hey, you! Stop”, the burglar turns round, sees the policeman and gives himself up. He puts his hands up and admits that he committed the break-in at the local shop.’ The subject is asked: ‘Why did the burglar do that?’ In line with the literature (Happé et al., 1999) a correct interpretation of the situation requires the subject to assess the burglar's mental state and to realize that he misunderstood the policeman's intention, which was to give back the glove.

RESULTS

Th.o.m.a.s

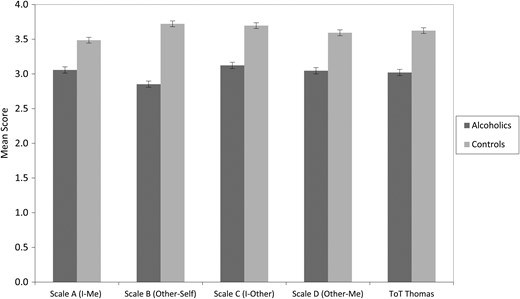

Figure 1 shows the mean total scores for AUD subjects and CS at each Th.o.m.a.s. scale (A, B, C and D) and the total mean Th.o.m.a.s. score.

AUD subjects' vs. controls' scores at the individual scales and at total Th.o.m.a.s., with standard error bars; AUD showed a worse performance on scale D (second-order ToM) than on scale A (first-order ToM), on scale B (third-person ToM) than on scale A (first-person ToM), on scale B (third-person ToM in allocentric perspective) than on scale C (third-person ToM in egocentric perspective) and on the total Th.o.m.a.s interview.

An independent samples t-test revealed that the total Th.o.m.a.s. score of the AUD subjects was worse than that of the CS (t = −5.15; P = 0.0001) (AUD mean = 3.09 ± . 48; CS mean = 3.7 ± 0.26). A repeated measures ANOVA was performed with a two-level between-subjects factor (Group: AUD vs. CS) and a four-level within-subjects factor (Th.o.m.a.s. scale type: A, I–Me; B, Other–Self; C, Me–Other; D, Other–Me). There was a main effect for the type of group (F(1,42) = 26.56; P = 0.0001; η = 0.387). In line with our hypothesis, AUD subjects performed worse than CS on all the Th.o.m.a.s. scales. Furthermore, there was evidence of a main effect of the scale type (F(3,42) = 11.77; P = 0.0001; η = 0.219), and the Group × Scale interaction was also significant (F(3,42) = 5.82; P = 001; η = 0.122), indicating a different pattern of performance between AUD and CS on the different Th.o.m.a.s. scales. To explore this result, we conducted a post hoc pairwise comparison using a Bonferroni correction (P < 0.05) in both the subjects with alcohol use disorder and the control group. The test revealed a significant difference both in AUD (P = 0.001) and in CS (P = 0.001), between Scale A, which assesses first-order ToM, and Scale D, which assesses second-order ToM. Both groups performed worse on Scale D than on Scale A (even if we expected this only for the AUD subjects). However, in line with our hypothesis, post hoc test revealed that AUD (P = 0.001)—but not CS (P = 0.783)—performed worse on Scale B, which assesses third-person ToM, than on Scale A, which assesses first-person ToM. The post hoc pairwise comparison also showed that AUD (P = 0.05)—but again not CS (P = 1)—performed worse on Scale B, which assesses third-person ToM from an allocentric perspective, than on scale C, which assesses third-person ToM from an egocentric perspective. That is, when alcoholics had to reason about others' mental states (third-person ToM), they found it harder to take an allocentric than an egocentric perspective.

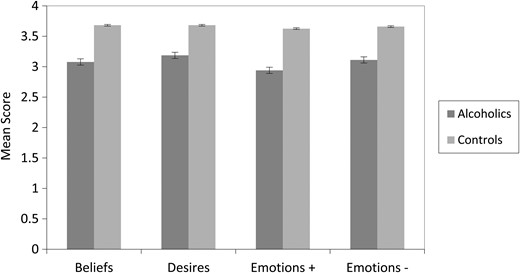

Figure 2 shows the mean score for the AUD and control groups for each kind of mental state type (beliefs, desires, positive emotions and negative emotions). A repeated measures ANOVA was performed with a two-level between-subjects factor (Group: AUD vs. CS) and a four-level within-subjects factor (mental state type: beliefs, desires, positive emotions and negative emotions). In line with our hypothesis the analysis showed a main effect of the type of group (F(1,42) = 26.96; P < 0.001; η = 0.391), indicating that AUD obtained lower scores than CS. There was also a main effect for the mental state type (F(3,42) = 8.56; P < 0.001; η = 0.169). The Group × mental state type was not significant (F(3,42) = 0.59; P = 6.18).

AUD subjects' vs. controls' scores on the four mental states types assessed by Th.o.m.a.s., with standard error bars; AUD performed worse than control subjects on all the mental state types.

Strange stories task

Contrary to our expectations, a t-test revealed no significant difference between AUD (mean = 0.849 ± 0.166) and CS (mean = 0.933 ± 0.117) on the Strange Stories task, although the percentages went in the expected directions.

Correlations within the AUD sample

Several analyses were carried out within the AUD sample in order to explore possible relations between the overall scores at the Th.o.m.a.s. and clinical variables of interest (age, education, duration of abstinence, duration of support, duration of abuse). No such significant relation was found, with the exception of a negative correlation (Pearson's correlation: r = −0.596; P = 0.003) between the AUD subjects' overall score at the Th.o.m.a.s. and the duration of abuse (see Table 2).

Correlations between the total Th.o.m.a.s. score, Th.o.m.a.s. scales, age, education, duration of therapy, outset, duration of abstinence, duration of abuse.

| . | Age . | Education . | Relief . | Outset . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th.o.m.a.s. | ||||||

| Total score | −0.29 | 0.19 | −0.12 | 0.09 | −0.22 | −0.59** |

| Scale | ||||||

| A (I–Me) | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.1 | −0.23 | −0.56** |

| B (Other–Self) | −0.24 | 0.09 | −0.1 | −0.01 | −0.15 | −0.45* |

| C (I–Other) | −0.28 | 0.29 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.13 | −0.58** |

| D (Other–Me) | −0.30 | 0.17 | −0.19 | 0.130 | −0.3 | −0.48* |

| . | Age . | Education . | Relief . | Outset . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th.o.m.a.s. | ||||||

| Total score | −0.29 | 0.19 | −0.12 | 0.09 | −0.22 | −0.59** |

| Scale | ||||||

| A (I–Me) | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.1 | −0.23 | −0.56** |

| B (Other–Self) | −0.24 | 0.09 | −0.1 | −0.01 | −0.15 | −0.45* |

| C (I–Other) | −0.28 | 0.29 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.13 | −0.58** |

| D (Other–Me) | −0.30 | 0.17 | −0.19 | 0.130 | −0.3 | −0.48* |

Durations are in months.

*P < 0.05.

**P < 0.01.

Correlations between the total Th.o.m.a.s. score, Th.o.m.a.s. scales, age, education, duration of therapy, outset, duration of abstinence, duration of abuse.

| . | Age . | Education . | Relief . | Outset . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th.o.m.a.s. | ||||||

| Total score | −0.29 | 0.19 | −0.12 | 0.09 | −0.22 | −0.59** |

| Scale | ||||||

| A (I–Me) | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.1 | −0.23 | −0.56** |

| B (Other–Self) | −0.24 | 0.09 | −0.1 | −0.01 | −0.15 | −0.45* |

| C (I–Other) | −0.28 | 0.29 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.13 | −0.58** |

| D (Other–Me) | −0.30 | 0.17 | −0.19 | 0.130 | −0.3 | −0.48* |

| . | Age . | Education . | Relief . | Outset . | Abstinence . | Duration of abuse . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th.o.m.a.s. | ||||||

| Total score | −0.29 | 0.19 | −0.12 | 0.09 | −0.22 | −0.59** |

| Scale | ||||||

| A (I–Me) | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.1 | −0.23 | −0.56** |

| B (Other–Self) | −0.24 | 0.09 | −0.1 | −0.01 | −0.15 | −0.45* |

| C (I–Other) | −0.28 | 0.29 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.13 | −0.58** |

| D (Other–Me) | −0.30 | 0.17 | −0.19 | 0.130 | −0.3 | −0.48* |

Durations are in months.

*P < 0.05.

**P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the research was to explore ToM impairments in severe chronic alcohol use disorder (AUD, or alcoholism). We adopted the Th.o.m.a.s., an interview aimed at an articulated exploration of ToM (Bosco et al., 2009a; Castellino et al., 2011) and an advanced ToM test, namely the Strange Stories test (Happé et al., 1999), aiming to provide a complete assessment of such complex cognitive ability.

Overall, the AUD group performed more poorly than the CS at each of the individual scales of the Th.o.m.a.s. (Scale A: first-person ToM; Scale B: third-person ToM from an allocentric perspective; Scale C: third-person ToM from an egocentric perspective; Scale D: second-order ToM task).

Additionally, our results revealed that the pattern of impairment varied across the different Th.o.m.a.s. scales. In particular the AUD subjects, but not the CS, performed worse at Scale B (third-person ToM allocentric perspective) than at Scales A (first-person ToM) and C (third-person ToM egocentric perspective). These findings indicate, for the first time in the literature, that persons with AUD, differently from healthy persons, find third-person considerations about mental states more difficult to make than first-person ones, and that when they adopt a third-person perspective they experience more difficulties in centring on another person's perspective than on the self.

Persons with AUD performed worse at Scale D (second-order ToM) than at Scale A (first-order ToM); however, this was true also of CS. Second-order ToM requires an advanced degree of mindreading ability and thus appears to be the task most difficult for healthy persons as well. This is in line with Astington (2003), who found that only 9 out of 24 healthy adults were able to fully comprehend an advanced ToM task that required a second-order reasoning on another person's belief.

Finally, persons with AUD achieved lower overall scores at each mental state type investigated by Th.o.m.a.s., namely beliefs, desires, positive emotions and negative emotions. There was no significant difference between AUD and CS in their performance among the different mental state types.

Overall our results appear to be in line with the literature (Uekermann et al., 2005). This strengthens the hypothesis that persons with AUD suffer from a deficit in their ability to ascribe and understand mental states in all the dimensions investigated, namely first- and third-person ToM, egocentric and allocentric perspectives, and first- and second-order ToM. Our results are also in line with the current literature to the effect that social cognition appears to be globally impaired in AUD (Philippot et al., 1999; Kornreich et al., 2002; Townshed and Duka, 2003; Uekermann et al., 2005; Foisy et al., 2007; Maurage et al., 2011a; Gizewski et al., 2012).

Surprisingly, our data revealed no significant difference between AUD subjects and controls at the Strange Stories (Happé et al., 1999), although the percentages went in the expected directions. However, this might be due to the fact that the latter task, while aimed at assessing a more sophisticated level of ToM than standard false-belief ones, was created in order to reveal severe ToM impairments like those of children with autism; therefore, it probably is not sensitive enough to evaluate more subtle dysfunctions.

No significant relations were found between overall scores on the Th.o.m.a.s. and the clinical variables of interest (age, education, duration of abstinence, duration of support, duration of abuse). This suggests that the ToM deficit in AUD may be substantially independent on other individual factors. The only exception is for the duration of abuse, which correlated negatively with both the overall scores and each Scale sub-score. This suggests a general progressive impairment of ToM abilities linked to alcohol abuse, which might be consistent with theories about brain damage, in particular with the ‘frontal lobe hypothesis’, i.e. the hypotheses of a vulnerability of the prefrontal cortex to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol and of a specific relation between this vulnerability and social cognition impairments (Uekermann and Daum, 2008).

It should be noted, however, that findings of an association between frontal lobe damage and ToM impairments have generally resulted from the use of false-belief tests (investigating the ability to infer that someone has a false belief in a specific context) (Apperly et al., 2004) and deception tests (investigating the ability to understand that someone is trying to deceive us) (Stuss et al., 2001). Executive functions (EF) (i.e. planning, attention, working memory, inhibitory control) appear to play a key role in both these kind of tests (Bloom and German 2000, Moses et al. 2009). Frontal lobe damage causes EF impairments (for a review see Jurado and Rosselli, 2007) and thus could indirectly affect ToM as evaluated by these tests, even though, as far as we know, no direct relation between frontal lobe deterioration and ToM impairment has actually been proven.

The Th.o.m.a.s. interview, by contrast, was built to require a minimal use of EF. Putting together these considerations, we suggest that cognitive loss due to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol on frontal lobes may not suffice to explain the poor performance of AUD subjects at Th.o.m.a.s.

Further studies are needed to investigate whether, and to what extent, social impairment may precede alcohol abuse, so as to assess the possibility of considering a weakness in ToM as a co-morbidity factor in the aetiology of abuse rather than one of its consequences.

In retrospect, there are certain limitations to our study. In particular, the sample was not as wide as would have been desirable, and was comparatively rather heterogeneous regarding the duration of abuse, the duration of abstinence and the pharmacological treatments that the participants underwent. Furthermore, additional measurements of cognitive functioning to correlate to ToM performance would be advisable in further studies.

To conclude, this is the first study to provide a complete and detailed assessment of ToM in subjects with AUD, exploring its complex nature, which is made up of differentiated but related abilities, as well as going beyond the classical focus of ToM research on the third-person allocentric perspective. Our data revealed a general impoverishment of ToM abilities in AUD, also suggesting that certain ToM components, namely third-person ToM and allocentric third-person mindreading, are more compromised than others. This confirms the hypothesis that ToM impairments may be inhomogeneous, at least to a certain extent, in clinical populations like AUD.

The clinical implication is that an articulated evaluation of ToM in patients with AUD may provide useful information for the treatment, so as to highlight possible priorities for intervention as well as the personal resources available for the patient. For example, a patient with severe impairment in third-person ToM might be expected to exhibit a correspondingly serious social maladaptation, which, in turn, would probably make her more vulnerable to relapse. Therefore, a clinical intervention focused on the patient's specific profile of impairment might positively affect the clinical prognosis.

Our results suggest that future studies should focus on the relevance of the different profiles of ToM impairments as predictors of treatment outcome in alcoholism and on the attempt to propose different rehabilitative interventions based on ToM assessment. A possible suggestion, for example, might be to use first-person social reasoning, which is less impaired than reasoning on the third person, as a lever for the rehabilitation of the latter.

Funding

This research was supported by University of Turin: Ricerca finanziata da Università (ex 60%): ‘Theory of Mind, executive functions and inferential ability in communicative-pragmatic ability’.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Antonio Murciano, Francesca Condello and Silvia De Fazio for the help in collecting data, the Aliseo Association and all the participants to the study.

REFERENCES

Appendix 1

THE INTERVIEW

This appendix contains the complete interview, divided into subscales. Th.o.m.a.s. being a semi-structured interview means that the interviewee's answers may sometimes anticipate questions that would have been the subject of a specific question at a later point. Analogously, explanations and examples may or may not be spontaneously offered by the interviewee. Therefore, a certain redundancy is present in the interview as it is reported here; this serves to remind the interviewer to ask for all the information needed, unless it has been spontaneously provided by the interviewee.

Scale A (I–Me)

[1] Do you happen to experience emotions that make you feel good? What? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[1a] (If the answer is negative) Why not?

[2] When you feel good, does that make any difference to you? What are the differences? Can you give an example of how you act or think, or of things that happen to you when you feel good?

[3] Do you happen to experience emotions that make you feel bad? What? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[3a] (If the answer is negative) Have you ever asked yourself why?

[4] When you feel bad, does that make any difference to you? What are the differences? Can you give an example of how you act or think, or of things that happen to you when you feel bad?

[5] When you feel bad, do you feel you understand why? Can you give an example?

[6] Can you change your mood, when you want to? How? On what occasions? Can you give me an example?

[6a] (If the answer is negative) Why not?

[7] Do you happen to have wishes, and know what you want? What? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[7a] (If the answer is negative) Do you ever ask yourself why?

[8] Do you try to fulfil your wishes? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[8a] (If the answer is negative) Why not?

[9] Do you succeed in getting what you want? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[10] Can you explain why you succeed/do not succeed?

Scale B (Other–Self)

[11] Do the other persons happen to experience emotions that make them feel good? What? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[11a] (If the answer is negative) Why not, in your opinion?

[12] When the others feel good, does that make any difference to them? What differences does it make? Can you give an example of how they act or think, or of things happening to them when they feel good?

[13] And do the other persons happen to experience emotions that make them feel bad? What? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[13a] (If the answer is negative) Why not, in your opinion?

[14] When the others feel bad, does that make any difference to them? What differences does it make? Can you give an example of how they act or think, or of things happening to them when they feel bad?

[15] In your opinion, when the others feel bad, do they understand why? Can you give an example?

[15a] (If the answer is negative) Why don't they understand, in your opinion?

[16] And, in your opinion, can the others change their mood when they want to? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[16a] (If the answer is negative) Why not, in your opinion?

[17] Do the others happen to have desires and know what they want? What sorts of desires do they have? Can you give an example?

[17a] (If the answer is negative) Why not, in your opinion?

[18] Do the others try to fulfil their desires? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[18a] (If the answer is negative) Why don't they try, in your opinion?

[19] In your opinion, do the others succeed in getting what they want? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[20] Why do/don't they succeed, in your opinion?

Scale C (I–Other)

[21] Do you notice when the others feel good? When does that happen? Can you give an example?

[21a] (If the answer is negative) Why don't you notice?

[22] When you notice that another person feels good, does that make any difference to you? What differences does it make? Can you give an example, of how you act or think, or of the things that happen to you?

[23] Do you notice when the others feel bad? When do you notice that? Can you give an example?

[23a] (If the answer is negative) Why don't you notice?

[24] When you notice that another person feels bad, does that make any difference to you? What differences does it make? Can you give an example of how you act or think, or of the things that happen to you?

[25] When the others feel bad, do you understand why? Can you give an example?

[25a] (If the answer is negative) Why can't you explain why other people feel bad?

[26] Do you ever want to influence the mood of the others? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[27] Do you succeed in doing so? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[28] How do you explain the fact that you manage/do not manage to do so?

[29] Do you think you understand the others' wishes? What sort of wishes do they have? Can you give an example?

Scale D (Other–Me)

[31] Do the others notice when you feel good? When do they notice? Can you give an example?

[31a] (If the answer is negative) Why don't they notice?

[32] When the others notice that you feel good, does that make any difference to them? What difference does it make? Can you give an example of how they act or think when they notice that you feel good?

[33] Do the others notice when you feel bad? When do they notice? Can you give an example?

[33a] (If the answer is negative) Why don't they notice?

[34] When the others notice that you feel bad, does that make any difference to them? What difference does it make? Can you give an example of how they act or think when they notice that you feel bad?

[35] When you feel bad, do the others understand why? Can you give an example?

[35a] (If the answer is negative) Why don't they understand?

[37] Can the others influence your mood? How? On what occasions? Can you give an example?

[38] How do you explain that they succeed/do not succeed in doing so?

[39] Do you think that the others understand your desires? In your opinion, what sort of wishes do they think you have? Can you give an example?

Appendix 2

RATING CRITERIA

This appendix contains the criteria used for scoring the answers. The interview is recorded (with the interviewee's permission) and transcribed; the answers are rated on the transcript. Each judge assigns each answer a score ranging from 0 to 4 and inserts it in the relevant cell; each cell thus corresponds to one answer given by the interviewee and represents the specific intersection between two of the dimensions investigated. The sample answers reported below are taken from actual interviews of the subjects who participated in the study

Score = 0

A score of 0 is attributed:

– when the interviewee remains silent, however encouraged by the interviewer;

– when the answer is incomprehensibly confused, or completely irrelevant to the question, or detached from reality;

Score = 1

A score of 1 is attributed:

– when the interviewee gains time without in fact providing any meaningful answer;

– when the interviewee says that she does not know how to answer or limits herself to replying yes or no without adding anything else, however encouraged by the interviewer;

– when the answer is confused or inconsistent with regard to the question;

– when an example is provided (spontaneously or after a request by the interviewer) which does not appear consistent with the rest of the answer;

Score = 2

A score of 2 is assigned to an answer which:

– is confused, albeit relevant to the question;

– is a mere repetition of the question without any further consideration or explanation (e.g. a tautological answer);

– expresses an emotional tone which is inconsistent with the question (e.g. an emotionally positive answer to a question concerning negative emotions);

– is not correctly aligned with the perspective required by the question, e.g. when the question concerns another person's emotional states (allocentric perspective) and the answer only refers to the interviewee herself (egocentric perspective);

Score = 3

A score of 3 is assigned to an answer which:

– is not articulated;

– is articulated and coherent, but provided with difficulty or only after several attempts on the part of the interviewer;

– is consistent with the question but has no concrete, meaningful example;

– provides an example which is approximate, generic, meaningless, or only refers to behaviours instead of mental states or events;

– is coherent and consistent, but generic, stereotyped or only slightly contextualized;

Score = 4

A score of 4 is attributed to an answer which:

– is coherent, detailed and organized, with significant, coherent and contextualized examples;

– refers in different ways to the interviewee's own mental states and events and to those of the others, thus providing not a generic or prototypical answer, but a contextualized one which bears a relation to the interviewee's personal experience or to an invented (but meaningful, detailed and well contextualized) example.