-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Craig C. Earle, Deborah Schrag, Bridget A. Neville, K. Robin Yabroff, Marie Topor, Angela Fahey, Edward L. Trimble, Diane C. Bodurka, Robert E. Bristow, Michael Carney, Joan L. Warren, Effect of Surgeon Specialty on Processes of Care and Outcomes for Ovarian Cancer Patients, JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Volume 98, Issue 3, 1 February 2006, Pages 172–180, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djj019

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background: For many diseases, specialized care (i.e., care rendered by a specialist) has been associated with superior-quality care (i.e., better outcomes). We examined associations between physician specialty and outcomes in a population-based cohort of elderly ovarian cancer surgery patients. Methods: We analyzed the Medicare claims, by physician specialty, of all women aged 65 years or older who underwent surgery for pathologically confirmed invasive epithelial ovarian cancer between January 1, 1992, and December 31, 1999, while living in an area monitored by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program to assess important care processes (i.e., the appropriate extent of surgery and use of adjuvant chemotherapy) and outcomes (i.e., surgical complications, ostomy rates, and survival). All statistical tests were two-sided. Results: Among 3067 ovarian cancer patients who underwent surgery, 1017 patients (33%) were treated by a gynecologic oncologist, 1377 patients (45%) by a general gynecologist, and 673 patients (22%) by a general surgeon. Among patients with stage I or II disease, those treated by a gynecologic oncologist (60%) were more likely to undergo lymph node dissection than those treated by a general gynecologist (36%) or a general surgeon (16%). Patients with stage III or IV disease were more likely to undergo a debulking procedure if the initial surgery was performed by a gynecologic oncologist (58%) than by a general gynecologist (51%) or a general surgeon (40%; P <.001) and were more likely to receive postoperative chemotherapy when operated on by a gynecologic oncologist (79%) or a general gynecologist (76%) than by a general surgeon (62%, P <.001). Survival among patients operated on by gynecologic oncologists (hazard ratio [HR] of death from any cause = 0.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.76 to 0.95) or general gynecologists (HR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.78 to 0.96) was better than that among patients operated on by general surgeons. Conclusions: Ovarian cancer patients treated by gynecologic oncologists had marginally better outcomes than those treated by general gynecologists and clearly superior outcomes compared with patients treated by general surgeons.

Among American women, ovarian cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths and the leading cause of gynecologic cancer deaths ( 1 ) . Ovarian cancer was expected to claim more than 16 000 lives in the United States in 2004, exceeding the total number claimed by all other gynecologic cancers combined. Nevertheless, approximately one-third of women who are diagnosed with ovarian cancer present with potentially curable disease ( 1 ) . Thus, the quality of care these women receive for the initial management of their disease is an important public health issue.

During the initial management of ovarian cancer, it is crucial that appropriate and high-quality surgical procedures be performed to obtain correct staging information, achieve optimal cytoreduction, and guide decisions about subsequent therapy. However, there is evidence that the recommended surgery for ovarian cancer is often not performed ( 2 ) . Several studies ( 3 – 6 ) found that more highly specialized surgeons (i.e., gynecologic oncologists) were more likely than less-specialized surgeons (i.e., general surgeons) to perform the recommended ( 7 ) surgery for ovarian cancer. Moreover, two studies ( 8 , 9 ) have shown that 20–30% of ovarian cancer patients thought to have early-stage disease were found to have had more advanced-stage disease at a second surgery if the appropriate staging procedures were not performed at the first surgery. Because of such observations, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and Society of Gynecologic Oncologists have recommended that all women with ovarian cancer except those suspected of having very early-stage cancer be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for the initial management of their disease ( 7 , 10 ) .

The purpose of this analysis was to examine whether there are systematic differences in the treatment rendered to women with ovarian cancer by virtue of the type of surgeon that provided the initial care. We compared the types of procedures performed and the outcomes achieved by three types of surgeons—gynecologic oncologists, general gynecologists, and general surgeons—to guide educational efforts within professional societies related to appropriate referral and to influence workforce planning and distribution of the various specialists needed to manage ovarian cancer patients.

M ETHODS

Data Sources

Ovarian cancer is a disease of elderly women, and women older than 65 years accounted for 43% of the ovarian cancer cases reported to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries in 1992 through 1999. We therefore used SEER registries linked to Medicare claims to assemble a population-based cohort of elderly ovarian cancer patients to examine specific quality-of-care measures.

SEER registries.

The 11 tumor registries that participate in the SEER program capture approximately 97% of the incident cancer cases for the regions they cover ( 11 ) and include a representative sample ( 12 ) of approximately 14% of the American population ( 13 ) . SEER registries collect data on each patient's age, sex, race and ethnicity, cancer site, stage of disease, histology, date of diagnosis, and date and cause of death. In addition, census-level sociodemographic data from the 2000 census have been linked to these cases.

Medicare data.

SEER registries do not capture complete treatment information. For example, SEER registries lack data on chemotherapy and any treatment given or planned more than 4 months after diagnosis. SEER data have been linked to Medicare claims for inpatient and outpatient care, physician and laboratory billings, and bills for home health and hospice care, with a match rate of 94% ( 14 ) . The linked SEER–Medicare data thus provide information about both the initial diagnosis and downstream medical care and allow patients aged 65 or older to be followed longitudinally. The Medicare dataset we used included claims from January 1, 1991, through December 31, 2001, that were linked to SEER data for cases diagnosed from January 1, 1992, through December 31, 1999.

AMA files.

We obtained information about physician characteristics, particularly the specialty type of the surgeon who performed cancer-directed procedures, by linking physicians' unique provider identification numbers in Medicare claims to data collected by the American Medical Association (AMA). When more than one surgeon was involved in the care of a patient, care was attributed to the most specialized surgeon. For example, if a gynecologic oncologist was ever involved in a patient's care, the patient was categorized as having been cared for by a gynecologic oncologist. If a gynecologic oncologist was not involved in a patient's care but a general gynecologist was, the patient's care was attributed to a general gynecologist. If neither a gynecologic oncologist nor a general gynecologist was involved in a patient's care, the patient was classified as having had their surgery performed by a general surgeon.

Hospital File.

We used the Hospital File (created by the National Cancer Institute), which contained information obtained from the following sources: data reported annually to the Healthcare Cost Report Information System by hospitals that bill to the Medicare and Medicaid programs and Provider of Service survey data reported periodically by health care institutions to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as part of its certification process. The National Cancer Institute extracts selected variables, such as whether the institution was a teaching hospital, from the Healthcare Cost Report Information System and Provider of Service files for data reported for 1996, 1998, and 2000 to create the Hospital File.

Cohort Selection

This study included all women 65 years or older who underwent surgery for pathologically confirmed invasive epithelial ovarian cancer between January 1, 1992, and December 31, 1999, while living in an area monitored by the SEER program. We excluded patients who were not eligible for both parts of Medicare or who were enrolled in a health maintenance organization at any time during the study period (24% of total).

Definitions of Explanatory Variables

Race was classified as white, black, or other. Stage of disease, including the number of lymph nodes examined, was based on clinical information reported to SEER registries. Socioeconomic status was approximated by using the median household income by census tract according to data from the 2000 U.S. Census. We identified comorbidities by searching inpatient and outpatient claims for diagnostic billing codes for various conditions during the year prior to the diagnosis of cancer, as suggested by Klabunde ( 15 ) , and by using the Deyo implementation ( 16 ) of the Charlson comorbidity score ( 17 ) . A patient was considered to have received their surgery in a teaching hospital if the institution was identified as such in the Hospital File.

Processes of Care

An expert panel of gynecologists and gynecologic oncologists (E. L. Trimble, D. C. Bodurka, R. E. Bristow, M. Carney) identified evidence-based measures of high-quality ovarian cancer care. These measures were operationalized as follows: For patients with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I or stage II ovarian cancer, we considered the proportion who underwent lymph node dissection and the number of lymph nodes examined as measures of the quality of care ( 18 ) . For patients with FIGO stage III or stage IV disease, we considered the proportion who underwent debulking and the proportion who received postoperative chemotherapy as indicators of care that should have occurred and the proportion who underwent a second-look surgery as an indicator of potential overuse of this procedure. Definitions for surgical procedures ( Appendix 1 ) and complications ( Appendix 2 ) were developed and evaluated by the expert panel. Surgical procedures were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, AMA Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and SEER-identified site-directed surgery codes. Codes used in these analyses are included in the appendices. Surgical procedures were grouped into two categories: the primary (i.e., cancer-directed) surgery and second-look surgeries.

Chemotherapy use was identified from billing claims by using standard algorithms that combine ICD-9-CM codes with Health Care Common Procedure Coding System codes, CPT codes, Diagnostic Related Group codes, and revenue center codes ( 19 ) ; chemotherapy was categorized as platinum containing or not based on Health Care Common Procedure Coding System codes for specific agents ( 20 ) .

Outcomes

We assessed the following outcomes as being potentially related to quality of care: surgical complications, ostomy rates, short-term (i.e., 30- and 60-day) surgical mortality, cause-specific mortality, and overall survival. Overall survival was defined as the time from the 15th day of the month of diagnosis until the date of death from any cause. A censoring date was determined for patients who were known to be alive during their last available Medicare coverage month.

Statistical Analysis

In univariate analyses, we compared patient characteristics and processes of care delivered by each type of surgeon by using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The Cochran-Armitage test was used to examine the statistical significance of trends in the use of specialized care over time. For variables that were found in the univariate analysis to be statistically significantly associated with being treated by a gynecologic oncologist (i.e., the receipt of specialized care), we used logistic regression to examine the simultaneous impact of multiple predictors of specialized care. Statistically significant explanatory variables were identified through forward selection, and interaction terms between the statistically significant variables were further investigated. Similar techniques were used to build Cox regression models of survival. The assumption of proportional hazards was verified by visual inspection of the hazard plot. All statistical analyses were two-sided and were performed using SAS version 8.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

R ESULTS

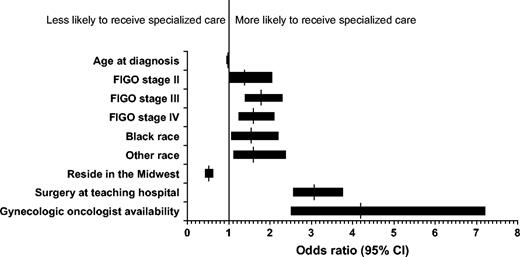

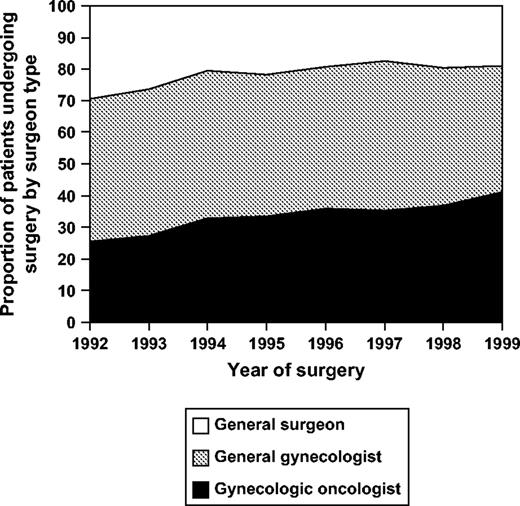

Among the 3067 patients who underwent surgery for ovarian cancer, 1017 patients (33%) were operated on by a gynecologic oncologist, 1377 patients (45%) were operated on by a general gynecologist, and 673 patients (22%) were operated on by a general surgeon. Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients by type of operating surgeon. The number of gynecologic oncologists per capita in areas monitored by the SEER program ranged from 1 per million residents in Iowa to 6.3 per million residents in Georgia. The per capita concentration of specialists was the factor most strongly associated with having had the primary surgery performed by one of these subspecialists (odds ratio [OR] of having surgery performed by a gynecologic oncologist versus by a general gynecologist or general surgeon was 4.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.5 to 7.2 for each gynecologic oncologist per million population) ( Fig. 1 ). Other statistically significant factors associated with having had a gynecologic oncologist perform the primary surgery were more advanced stage of disease (OR for stage II versus stage I = 1.43 [95% CI = 1.01 to 2.04]; OR for stage III versus stage I = 1.78 [95% CI = 1.39 to 2.28]; OR for stage IV versus stage I = 1.60 [95% CI = 1.24 to 2.07]), nonwhite race (OR for black versus white = 1.54 [95% CI = 1.07 to 2.24]; OR for other race versus white = 1.62 [95% CI = 1.12 to 2.35]) and having surgery in a teaching hospital (OR = 3.09 [95% CI = 2.55 to 3.74]). Older age of the patient at diagnosis (OR for each increasing year of age = 0.98 [95% CI = 0.97 to 0.99]) and residing in the Midwest versus in the West (OR = 0.51 [95% CI = 0.42 to 0.61]) were both associated with a decreased odds of being treated by a gynecologic oncologist ( Fig. 1 ). There was also a secular trend toward more provision of care by gynecologic oncologists; they operated on 25% of patients in 1992 and on 41% of patients in 1999 ( Ptrend <.001) ( Fig. 2 ).

Predictors of having a gynecologic oncologist perform primary surgery. Vertical lines = odds ratios; horizontal bars = 95% confidence intervals. FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; gynecologic oncologist availability = per capita state concentration of gynecologic oncologists; CI = confidence interval.

Trends in specialized ovarian cancer care over time. Proportion of patients operated upon by each type of surgeon by year of diagnosis. Ptrend <.001 (Cochran-Armitage test) for increasing proportion done by gynecologic oncologists over time.

Demographics of ovarian cancer patients who underwent surgery, by surgeon type ( n = 3067) *

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1017 | 1377 | 673 |

| Mean age at diagnosis, y (SD) | 74.0 (5.6) | 74.6 (6.1) | 75.5 (6.4) |

| Race, no. (%) | |||

| White | 890 (87.5) | 1274 (92.5) | 612 (90.9) |

| Black | 63 (6.2) | 45 (3.3) | 29 (4.3) |

| Other | 63 (6.2) | 51 (3.7) | 25 (3.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.5) | 7 (1.0) |

| Urban county of residence, no. (%) | 947 (93.1) | 1268 (92.1) | 561 (83.4) |

| Treated at a teaching hospital, no. (%) | 803 (79.0) | 835 (60.6) | 370 (55.0) |

| Avg median income in census tract, $ | 55 360 | 54 279 | 50 438 |

| Charlson comorbidity score, no. (%) † | |||

| 0 | 753 (74.0) | 1029 (74.7) | 523 (77.7) |

| 1 | 186 (18.3) | 244 (17.7) | 108 (16.1) |

| ≥2 | 78 (7.7) | 104 (7.6) | 42 (6.2) |

| FIGO stage, no. (%) | |||

| I | 119 (11.7) | 268 (19.5) | 100 (14.9) |

| II | 79 (7.8) | 141 (10.2) | 44 (6.5) |

| III | 484 (47.6) | 566 (41.1) | 274 (40.7) |

| IV | 335 (32.9) | 402 (29.2) | 255 (37.9) |

| Region of residence, no. (%) | |||

| Northeast | 143 (14.1) | 188 (13.7) | 48 (7.1) |

| South | 90 (8.9) | 71 (5.2) | 41 (6.1) |

| Midwest | 257 (25.3) | 442 (32.1) | 248 (36.9) |

| West | 527 (51.8) | 676 (49.1) | 336 (49.9) |

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1017 | 1377 | 673 |

| Mean age at diagnosis, y (SD) | 74.0 (5.6) | 74.6 (6.1) | 75.5 (6.4) |

| Race, no. (%) | |||

| White | 890 (87.5) | 1274 (92.5) | 612 (90.9) |

| Black | 63 (6.2) | 45 (3.3) | 29 (4.3) |

| Other | 63 (6.2) | 51 (3.7) | 25 (3.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.5) | 7 (1.0) |

| Urban county of residence, no. (%) | 947 (93.1) | 1268 (92.1) | 561 (83.4) |

| Treated at a teaching hospital, no. (%) | 803 (79.0) | 835 (60.6) | 370 (55.0) |

| Avg median income in census tract, $ | 55 360 | 54 279 | 50 438 |

| Charlson comorbidity score, no. (%) † | |||

| 0 | 753 (74.0) | 1029 (74.7) | 523 (77.7) |

| 1 | 186 (18.3) | 244 (17.7) | 108 (16.1) |

| ≥2 | 78 (7.7) | 104 (7.6) | 42 (6.2) |

| FIGO stage, no. (%) | |||

| I | 119 (11.7) | 268 (19.5) | 100 (14.9) |

| II | 79 (7.8) | 141 (10.2) | 44 (6.5) |

| III | 484 (47.6) | 566 (41.1) | 274 (40.7) |

| IV | 335 (32.9) | 402 (29.2) | 255 (37.9) |

| Region of residence, no. (%) | |||

| Northeast | 143 (14.1) | 188 (13.7) | 48 (7.1) |

| South | 90 (8.9) | 71 (5.2) | 41 (6.1) |

| Midwest | 257 (25.3) | 442 (32.1) | 248 (36.9) |

| West | 527 (51.8) | 676 (49.1) | 336 (49.9) |

Some percentages do not total 100 due to rounding. SD = standard deviation; FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Demographics of ovarian cancer patients who underwent surgery, by surgeon type ( n = 3067) *

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1017 | 1377 | 673 |

| Mean age at diagnosis, y (SD) | 74.0 (5.6) | 74.6 (6.1) | 75.5 (6.4) |

| Race, no. (%) | |||

| White | 890 (87.5) | 1274 (92.5) | 612 (90.9) |

| Black | 63 (6.2) | 45 (3.3) | 29 (4.3) |

| Other | 63 (6.2) | 51 (3.7) | 25 (3.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.5) | 7 (1.0) |

| Urban county of residence, no. (%) | 947 (93.1) | 1268 (92.1) | 561 (83.4) |

| Treated at a teaching hospital, no. (%) | 803 (79.0) | 835 (60.6) | 370 (55.0) |

| Avg median income in census tract, $ | 55 360 | 54 279 | 50 438 |

| Charlson comorbidity score, no. (%) † | |||

| 0 | 753 (74.0) | 1029 (74.7) | 523 (77.7) |

| 1 | 186 (18.3) | 244 (17.7) | 108 (16.1) |

| ≥2 | 78 (7.7) | 104 (7.6) | 42 (6.2) |

| FIGO stage, no. (%) | |||

| I | 119 (11.7) | 268 (19.5) | 100 (14.9) |

| II | 79 (7.8) | 141 (10.2) | 44 (6.5) |

| III | 484 (47.6) | 566 (41.1) | 274 (40.7) |

| IV | 335 (32.9) | 402 (29.2) | 255 (37.9) |

| Region of residence, no. (%) | |||

| Northeast | 143 (14.1) | 188 (13.7) | 48 (7.1) |

| South | 90 (8.9) | 71 (5.2) | 41 (6.1) |

| Midwest | 257 (25.3) | 442 (32.1) | 248 (36.9) |

| West | 527 (51.8) | 676 (49.1) | 336 (49.9) |

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1017 | 1377 | 673 |

| Mean age at diagnosis, y (SD) | 74.0 (5.6) | 74.6 (6.1) | 75.5 (6.4) |

| Race, no. (%) | |||

| White | 890 (87.5) | 1274 (92.5) | 612 (90.9) |

| Black | 63 (6.2) | 45 (3.3) | 29 (4.3) |

| Other | 63 (6.2) | 51 (3.7) | 25 (3.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.5) | 7 (1.0) |

| Urban county of residence, no. (%) | 947 (93.1) | 1268 (92.1) | 561 (83.4) |

| Treated at a teaching hospital, no. (%) | 803 (79.0) | 835 (60.6) | 370 (55.0) |

| Avg median income in census tract, $ | 55 360 | 54 279 | 50 438 |

| Charlson comorbidity score, no. (%) † | |||

| 0 | 753 (74.0) | 1029 (74.7) | 523 (77.7) |

| 1 | 186 (18.3) | 244 (17.7) | 108 (16.1) |

| ≥2 | 78 (7.7) | 104 (7.6) | 42 (6.2) |

| FIGO stage, no. (%) | |||

| I | 119 (11.7) | 268 (19.5) | 100 (14.9) |

| II | 79 (7.8) | 141 (10.2) | 44 (6.5) |

| III | 484 (47.6) | 566 (41.1) | 274 (40.7) |

| IV | 335 (32.9) | 402 (29.2) | 255 (37.9) |

| Region of residence, no. (%) | |||

| Northeast | 143 (14.1) | 188 (13.7) | 48 (7.1) |

| South | 90 (8.9) | 71 (5.2) | 41 (6.1) |

| Midwest | 257 (25.3) | 442 (32.1) | 248 (36.9) |

| West | 527 (51.8) | 676 (49.1) | 336 (49.9) |

Some percentages do not total 100 due to rounding. SD = standard deviation; FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of each group of surgeons. Although there were fewer gynecologic oncologists than general gynecologists or general surgeons, gynecologic oncologists treated approximately one-third of the cohort and thus had the highest case volumes. Almost all of the gynecologic oncologists (99%) were board certified in their specialty, compared with 92% of the general gynecologists and only 80% of the general surgeons. In addition, more gynecologic oncologists than general gynecologists or surgeons were recent medical school graduates: Most of the gynecologic oncologists had graduated in the 1980s, whereas most of the general gynecologists and surgeons had graduated in the 1970s.

Characteristics of surgeons ( n =1204)

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of surgeons (%) | 115 (10) | 640 (53) | 449 (37) | |

| No. of patients (%) ( n = 2995) | 1017 (34) | 1377 (46) | 601 (20) † | |

| Mean no. of operations ‡ | 8.8 | 2.2 | 1.3 | <.001 |

| Board certified, no. (%) | 114 (99) | 587 (92) | 357 (80) | <.001 |

| Year graduated from medical school, no. (%) | ||||

| Before 1950 | 0 (0) | 15 (2) | 101 (22) | |

| 1950–1959 | 6 (5) | 73 (11) | 41 (9) | |

| 1960–1969 | 27 (23) | 149 (23) | 95 (21) | |

| 1970–1979 | 30 (26) | 191 (30) | 115 (26) | |

| 1980–1989 | 47 (41) | 175 (27) | 88 (20) | |

| 1990 or later | 5 (4) | 37 (6) | 9 (2) |

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of surgeons (%) | 115 (10) | 640 (53) | 449 (37) | |

| No. of patients (%) ( n = 2995) | 1017 (34) | 1377 (46) | 601 (20) † | |

| Mean no. of operations ‡ | 8.8 | 2.2 | 1.3 | <.001 |

| Board certified, no. (%) | 114 (99) | 587 (92) | 357 (80) | <.001 |

| Year graduated from medical school, no. (%) | ||||

| Before 1950 | 0 (0) | 15 (2) | 101 (22) | |

| 1950–1959 | 6 (5) | 73 (11) | 41 (9) | |

| 1960–1969 | 27 (23) | 149 (23) | 95 (21) | |

| 1970–1979 | 30 (26) | 191 (30) | 115 (26) | |

| 1980–1989 | 47 (41) | 175 (27) | 88 (20) | |

| 1990 or later | 5 (4) | 37 (6) | 9 (2) |

Two-sided analysis of variance.

Provider data were not available for 72 patients.

Number of patients operated upon by a surgeon in each specialty, divided by the number of surgeons in that specialty.

Characteristics of surgeons ( n =1204)

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of surgeons (%) | 115 (10) | 640 (53) | 449 (37) | |

| No. of patients (%) ( n = 2995) | 1017 (34) | 1377 (46) | 601 (20) † | |

| Mean no. of operations ‡ | 8.8 | 2.2 | 1.3 | <.001 |

| Board certified, no. (%) | 114 (99) | 587 (92) | 357 (80) | <.001 |

| Year graduated from medical school, no. (%) | ||||

| Before 1950 | 0 (0) | 15 (2) | 101 (22) | |

| 1950–1959 | 6 (5) | 73 (11) | 41 (9) | |

| 1960–1969 | 27 (23) | 149 (23) | 95 (21) | |

| 1970–1979 | 30 (26) | 191 (30) | 115 (26) | |

| 1980–1989 | 47 (41) | 175 (27) | 88 (20) | |

| 1990 or later | 5 (4) | 37 (6) | 9 (2) |

| Characteristic . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of surgeons (%) | 115 (10) | 640 (53) | 449 (37) | |

| No. of patients (%) ( n = 2995) | 1017 (34) | 1377 (46) | 601 (20) † | |

| Mean no. of operations ‡ | 8.8 | 2.2 | 1.3 | <.001 |

| Board certified, no. (%) | 114 (99) | 587 (92) | 357 (80) | <.001 |

| Year graduated from medical school, no. (%) | ||||

| Before 1950 | 0 (0) | 15 (2) | 101 (22) | |

| 1950–1959 | 6 (5) | 73 (11) | 41 (9) | |

| 1960–1969 | 27 (23) | 149 (23) | 95 (21) | |

| 1970–1979 | 30 (26) | 191 (30) | 115 (26) | |

| 1980–1989 | 47 (41) | 175 (27) | 88 (20) | |

| 1990 or later | 5 (4) | 37 (6) | 9 (2) |

Two-sided analysis of variance.

Provider data were not available for 72 patients.

Number of patients operated upon by a surgeon in each specialty, divided by the number of surgeons in that specialty.

Table 3 shows the processes of care measures identified by the expert panel as being important for high-quality ovarian cancer care and the rates of these measures achieved by each group of surgeons. Patients treated by each of the three types of surgeons had similar rates of multiple surgeries during the peridiagnostic period (approximately 4%). All three groups of patients had similar complication rates (most commonly bowel obstruction, nausea, and dehydration; data not shown) as well as similar rehospitalization rates (approximately 12%) within 60 days of surgery. Among patients with stage I or stage II ovarian cancer, more of those treated by gynecologic oncologists underwent lymph node dissection than of those treated by general gynecologists or general surgeons (60% versus 36% and 16%, respectively; P <.001). Among the patients who underwent lymph node dissection, those treated by gynecologic oncologists had more lymph nodes examined than those treated by general gynecologists or general surgeons, but the difference was not statistically significant because of small numbers (average numbers of lymph nodes examined, 12, 10, and 6, respectively; P = .50 by analysis of variance).

Processes of care by surgeon type *

| Process . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||||

| No. of patients requiring >1 surgery/total no. of patients (%) | 40/1017 (4) | 62/1377 (4) | 27/673 (4) | .76 |

| FIGO stage I or II patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent lymph node dissection/total no. of stage I and II patients (%) | 118/198 (60) | 146/409 (36) | 23/144 (16) | <.001 |

| Mean no. of regional lymph nodes examined (no. of patients for whom lymph node data were available) | 12 (27) | 10 (36) | 6 (6) | .50 ‡ |

| FIGO stage III or IV patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent debulking/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 473/819 (58) | 490/968 (51) | 211/529 (40) | <.001 |

| No. of patients who underwent second-look surgery/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 161/819 (20) | 235/968 (24) | 106/529 (20) | .04 |

| No. of patients who received postoperative chemotherapy/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 650/819 (79) | 732/968 (76) | 327/529 (62) | <.001 |

| Process . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||||

| No. of patients requiring >1 surgery/total no. of patients (%) | 40/1017 (4) | 62/1377 (4) | 27/673 (4) | .76 |

| FIGO stage I or II patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent lymph node dissection/total no. of stage I and II patients (%) | 118/198 (60) | 146/409 (36) | 23/144 (16) | <.001 |

| Mean no. of regional lymph nodes examined (no. of patients for whom lymph node data were available) | 12 (27) | 10 (36) | 6 (6) | .50 ‡ |

| FIGO stage III or IV patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent debulking/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 473/819 (58) | 490/968 (51) | 211/529 (40) | <.001 |

| No. of patients who underwent second-look surgery/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 161/819 (20) | 235/968 (24) | 106/529 (20) | .04 |

| No. of patients who received postoperative chemotherapy/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 650/819 (79) | 732/968 (76) | 327/529 (62) | <.001 |

FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Two-sided chi-square test except where noted.

Two-sided analysis of variance.

Processes of care by surgeon type *

| Process . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||||

| No. of patients requiring >1 surgery/total no. of patients (%) | 40/1017 (4) | 62/1377 (4) | 27/673 (4) | .76 |

| FIGO stage I or II patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent lymph node dissection/total no. of stage I and II patients (%) | 118/198 (60) | 146/409 (36) | 23/144 (16) | <.001 |

| Mean no. of regional lymph nodes examined (no. of patients for whom lymph node data were available) | 12 (27) | 10 (36) | 6 (6) | .50 ‡ |

| FIGO stage III or IV patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent debulking/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 473/819 (58) | 490/968 (51) | 211/529 (40) | <.001 |

| No. of patients who underwent second-look surgery/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 161/819 (20) | 235/968 (24) | 106/529 (20) | .04 |

| No. of patients who received postoperative chemotherapy/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 650/819 (79) | 732/968 (76) | 327/529 (62) | <.001 |

| Process . | Gynecologic oncologist . | General gynecologist . | General surgeon . | P† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||||

| No. of patients requiring >1 surgery/total no. of patients (%) | 40/1017 (4) | 62/1377 (4) | 27/673 (4) | .76 |

| FIGO stage I or II patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent lymph node dissection/total no. of stage I and II patients (%) | 118/198 (60) | 146/409 (36) | 23/144 (16) | <.001 |

| Mean no. of regional lymph nodes examined (no. of patients for whom lymph node data were available) | 12 (27) | 10 (36) | 6 (6) | .50 ‡ |

| FIGO stage III or IV patients | ||||

| No. of patients who underwent debulking/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 473/819 (58) | 490/968 (51) | 211/529 (40) | <.001 |

| No. of patients who underwent second-look surgery/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 161/819 (20) | 235/968 (24) | 106/529 (20) | .04 |

| No. of patients who received postoperative chemotherapy/total no. of stage III and IV patients (%) | 650/819 (79) | 732/968 (76) | 327/529 (62) | <.001 |

FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Two-sided chi-square test except where noted.

Two-sided analysis of variance.

Among patients with stage III or IV disease, those treated by gynecologic oncologists and general gynecologists had the most similar processes of care ( Table 3 ). Patients operated on by gynecologic oncologists or general gynecologists were more likely to undergo a debulking procedure at the time of their first surgery than patients operated on by general surgeons (58% and 51%, respectively, versus 40%, P <.001) and were more likely to receive postoperative chemotherapy (79% and 76%, respectively, versus 62%, P <.001). When chemotherapy was given, all three types of providers were equally likely to give platinum-based chemotherapy (data not shown). Patients operated on by general surgeons were more likely to require an ostomy than patients operated on by gynecologic oncologists or general gynecologists (26% versus 19% and 16%, respectively; P <.001). This observation may reflect those patients' mode of presentation, however, as general surgeons were also more likely than gynecologic oncologists or general gynecologists to operate on patients who were admitted on the basis of a medical emergency such as bowel obstruction (8% versus 5% and 4%, respectively; P <.001). When we excluded from the analysis patients who presented through an emergency room prior to surgery, ostomy rates became similar among the three surgeon groups but rates of the other processes and outcomes were unchanged (data not shown). Patients treated by general gynecologists were more likely to undergo a second-look surgery than those treated by gynecologic oncologists or general surgeons (24% versus 20% and 20%, respectively; P = .04).

At 30 days after the most extensive surgical procedure, the mortality rates were 2.1% (95% CI = 1.4% to 3.1%) for patients treated by gynecologic oncologists, 2.1% (95% CI = 1.5% to 3.0%) for patients treated by general gynecologists, and 4% (95% CI = 2.9% to 6.0%) for patients treated by general surgeons ( P = .01; chi-square test). At 60 days after the most extensive surgical procedure, the mortality rates were 5.4% (95% CI = 4.2% to 7.0%), 6.4% (95% CI = 5.2% to 7.8%), and 12.3% (95% CI = 10.1% to 15.0%), respectively ( P <.001, chi-square test). Median survival was 32.5 months (95% CI = 30.4 months to 34.5 months), 35.6 months (95% CI = 32.5 months to 38.6 months), and 24.3 months (95% CI = 22.3 months to 27.4 months), respectively. In a Cox model adjusted for age at diagnosis, stage, and comorbidity, the hazard ratios for death from any cause were 0.85 (95% CI = 0.76 to 0.95) for patients of gynecologic oncologists versus patients of general surgeons and 0.86 (95% CI = 0.78 to 0.96) for patients of general gynecologists versus patients of general surgeons ( Table 4 ). Other factors associated with better survival were younger age at diagnosis, less comorbidity, and earlier stage of disease.

Cox proportional hazards model for death from any cause *

| Variable . | HR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|

| Gynecologic oncologist † | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95) |

| General gynecologist † | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.96) |

| Age at diagnosis ‡ | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.06) |

| Charlson score § | 1.30 (1.22 to 1.38) |

| FIGO stage II ∥ | 2.20 (1.79 to 2.70) |

| FIGO stage III ∥ | 4.23 (3.63 to 4.94) |

| FIGO stage IV | 5.34 (4.57 to 6.25) |

| Variable . | HR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|

| Gynecologic oncologist † | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95) |

| General gynecologist † | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.96) |

| Age at diagnosis ‡ | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.06) |

| Charlson score § | 1.30 (1.22 to 1.38) |

| FIGO stage II ∥ | 2.20 (1.79 to 2.70) |

| FIGO stage III ∥ | 4.23 (3.63 to 4.94) |

| FIGO stage IV | 5.34 (4.57 to 6.25) |

FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Compared with general surgeon.

For every 1-year increase in age.

For increasing Charlson score.

Compared with FIGO stage I.

Cox proportional hazards model for death from any cause *

| Variable . | HR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|

| Gynecologic oncologist † | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95) |

| General gynecologist † | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.96) |

| Age at diagnosis ‡ | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.06) |

| Charlson score § | 1.30 (1.22 to 1.38) |

| FIGO stage II ∥ | 2.20 (1.79 to 2.70) |

| FIGO stage III ∥ | 4.23 (3.63 to 4.94) |

| FIGO stage IV | 5.34 (4.57 to 6.25) |

| Variable . | HR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|

| Gynecologic oncologist † | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95) |

| General gynecologist † | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.96) |

| Age at diagnosis ‡ | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.06) |

| Charlson score § | 1.30 (1.22 to 1.38) |

| FIGO stage II ∥ | 2.20 (1.79 to 2.70) |

| FIGO stage III ∥ | 4.23 (3.63 to 4.94) |

| FIGO stage IV | 5.34 (4.57 to 6.25) |

FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Compared with general surgeon.

For every 1-year increase in age.

For increasing Charlson score.

Compared with FIGO stage I.

We also analyzed the data by attributing the processes and outcomes of care to the surgeon type that performed the first ovarian cancer–directed surgery, rather than to the most specialized surgeon type performing any ovarian cancer–directed surgery, and found similar results (data not shown). Similar results were also obtained when we considered only ovarian cancer-specific mortality in the Cox model, except that the hazard of death for patients with stage III disease versus stage I disease increased from 4.23 (95% CI = 3.63 to 4.94) to 7.20 (95% CI = 5.59 to 9.27); for patients with stage IV disease versus stage I disease, it increased from 5.34 (4.57 to 6.25) to 10.28 (95% CI = 7.97 to 13.26). There was no differential effect of surgeon type on survival when the analysis was limited to patients with stage I or stage II disease or to patients with III or stage IV disease or when 2-year survival rates were analyzed (data not shown). Although the gynecologic oncologists were more likely to practice in larger hospitals (i.e., hospitals with more intensive-care unit beds) than the general gynecologists, and although the general gynecologists were more likely to operate in larger hospitals than the general surgeons, we found no association between hospital size and survival for this cohort of patients (data not shown). We also found that surgeon case volume was not statistically significantly associated with survival in any model as long as surgeon specialty was included in the model. Associations between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and ovarian cancer outcomes are addressed in the companion paper by Schrag et al. ( 21 ) .

D ISCUSSION

Our results suggest that the initial management of ovarian cancer by specialist surgeons (i.e., gynecologic oncologists) is associated with better quality of care and outcomes. We found that, among patients diagnosed with early-stage disease, those operated on by gynecologic oncologists had better processes of care than those operated on by general gynecologists or general surgeons. Specifically, gynecologic oncologists were more likely than general gynecologists and general surgeons to perform appropriately aggressive surgery and to provide indicated postoperative chemotherapy and less likely to perform generally unnecessary procedures, such as second-look laparotomies. Among patients with advanced disease at diagnosis, those treated by gynecologic oncologists and general gynecologists had similar and higher rates of appropriate care than those treated by general surgeons. Although patients operated on by gynecologic oncologists tended to have more advanced disease at diagnosis, their survival rates were similar to those of patients operated on by general gynecologists and better than those of patients operated on by general surgeons. However, only a minority of patients included in our study had their initial surgery performed by a gynecologic oncologist, although this proportion increased during the study period.

Appropriate decisions about the management of ovarian cancer, such as those concerning the use of postoperative chemotherapy, rely on accurate surgical staging. The literature suggests that almost half of the patients who undergo surgical exploration for ovarian cancer are incompletely staged ( 4 , 22 ) and that 31% of patients who undergo surgical exploration will be found to actually have a cancer of higher stage than was previously thought before they underwent the appropriate procedure ( 8 ) . Moreover, McGowan et al. ( 4 ) have also observed that the rates of complete staging at initial ovarian cancer operations depend on the specialty of the surgeon and range from 35% for general surgeons to 52% for general gynecologists and 97% for gynecologic oncologists. Commonly missed staging procedures include visualization and palpation of the diaphragm, assessment of peritoneal fluid, and biopsies of serosal surfaces and implants.

We also found that subspecialized surgeons (i.e., gynecologic oncologists) appeared to provide subsequent care that was more in keeping with NIH-defined best practices than that provided by either general gynecologists or general surgeons. In 1997, Munoz et al. ( 2 ) estimated that only a minority of ovarian cancer patients with early-stage disease were treated according to NIH guidelines. For example, they observed that general gynecologists were more likely to perform second-look laparotomies, which are not routinely recommended. Others ( 6 ) have also noted associations between operations performed by nonspecialized surgeons and higher rates of morbidity, ostomy formation, and mortality. We did not detect differential morbidity rates, however, possibly because of unaccounted for differences in case mix, such as patients of more specialized surgeons being generally of poorer prognosis to start with or different billing practices among surgeon specialties systematically affecting the ability to detect complications in claims.

The surgeon groups we examined differed in several ways. The gynecologic oncologists tended to be younger than the general gynecologists or the general surgeons, were more likely to practice in teaching hospitals than in the community, and tended to be higher-volume providers than the other surgeon groups ( 21 ) . In addition, the type of hospital patients go to for ovarian cancer treatment has been found to be related to the completeness of their intraoperative evaluation, which ranges from 46% complete in community hospitals to 66% complete in university-affiliated hospitals ( 4 ) . These observations are probably related. Our finding that patients with later-stage disease were frequently operated on by gynecologic oncologists may reflect the fact that such patients were selected for specialized care. The fact that specialized surgeons appeared more likely to do more extensive surgery, however, suggests that the alternative possibility may also be true, i.e., that some of the patients seen by nonspecialized surgeons may not have been completely staged. The fact that patients who received specialized care had better survival despite presenting with later-stage disease supports this hypothesis.

The limitations of this study are those inherent in studies involving administrative data analysis. For example, many relevant clinical parameters, such as information about prior gynecologic surgery or presenting signs and symptoms that would inform a preoperative “risk-of-malignancy index” ( 23 ) used to identify patients most likely to benefit from specialized care, are not included in Medicare data. In addition, Medicare data reveal only that debulking was done, not the degree of cytoreduction that was achieved. Moreover, it is possible that our results may at least partially reflect differences in Medicare billing practices by specialty rather than differences in clinical practice. In addition, patients who receive their care in health maintenance organizations may have different characteristics and experience different processes of care compared with those in fee-for-service settings. Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients were known only at the level of the census tract. In addition, surgeons may have been misclassified either by their specialty designation or by the approach of attributing the processes and outcomes of care to specialists if they were ever involved in the care of the patient, regardless of their degree of involvement. Finally, these results in elderly patients in limited geographic regions in a fee-for-service environment may not translate to other populations or settings.

Our data support professional societies' recommendations that it is preferable for ovarian cancer patients to be operated on by gynecologic oncologists when possible. Although the relative contributions of specialized training and surgeon volume to the observed improved outcomes requires further study, our results suggest that the expertise required to know how to treat a patient, i.e., to perform an appropriately extensive surgery and the postoperative chemotherapy, if indicated, is at least as important as technical skill that would be reflected in the volume-outcome relationship alone. Raising awareness of these issues, addressing limitations in the availability and distribution of more specialized surgeons, and removing barriers to access to specialized care ( 5 , 24 ) may have as great an impact on the burden of this disease as many of our best chemotherapy regimens.

Billing codes for and classification of surgical procedures *

| Procedure code(s) . | Description . | Cancer-directed surgery . | Second-look surgery . | Debulking . | Ostomy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 | |||||

| 65.2 | Wedge resection or partial excision of ovary | X | |||

| 65.3x | Unilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.4x | Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.5x | Bilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.6x | Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 68.8 | Pelvic evisceration | X | X | ||

| 43.1 | Gastrostomy, includes PEG (43.11) and other (43.19) | X | |||

| 46.32 | PEJ | X | |||

| 46.39 | Feeding jejunostomy | X | |||

| 46.0–46.24 | Colostomy or ileostomy | X | |||

| 54.1 | Laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.11 | Exploratory laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.21 | Laparoscopy | X | |||

| 68.3–68.7, 68.9 | Hysterectomy | X | |||

| CPT | |||||

| 56303 | Laparoscopy with excision of ovary or peritoneum | X | |||

| 56307 | Laparoscopic oophorectomy +/− salpingectomy | X | |||

| 56308 | Laparoscopy and vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 57531 | Para-aortic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58150 | TAH +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58152 | TAH with colpo-urethrocystopexy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58180 | Subtotal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58200 | TAH with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58210 | Radical hysterectomy | X | |||

| 58240 | Pelvic exenteration, including colostomy | X | X | ||

| 58262 | Vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58263 | Vaginal hysterectomy with repair of enterocele +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58720 | Salpingo-oophorectomy, complete or partial, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58920 | Wedge resection of ovary | X | |||

| 58940 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58943 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral; for ovarian malignancy, with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node biopsies, peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsies, diaphragmatic assessments, with or without salpingectomy(s), with or without omentectomy | X | |||

| 58950 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; | X | |||

| 58951 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with total abdominal hysterectomy, pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 58952 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with radical dissection for debulking | X | X | ||

| 43246 | Endoscopy with percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43750 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43760 | Change of gastrostomy tube | X | |||

| 43761 | Duodenal feeding tube | X | |||

| 43830 | Temporary gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43832 | Permanent gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 44015 | Surgical placement of jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44125 | Enterectomy, resection of small intestine; with enterostomy | X | |||

| 44130 | Enteroenterostomy, anastomosis of intestine, with or without cutaneous enterostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44141 | Colectomy, partial; with skin level cecostomy or colostomy | X | |||

| 44143 | Colectomy, partial; with end colostomy and closure of distal segment (Hartmann type procedure) | X | |||

| 44144 | Colectomy, partial; with resection, with colostomy or ileostomy and creation of mucofistula | X | |||

| 44146 | Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic anastomosis), with colostomy | X | |||

| 44150 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy | X | |||

| 44151 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44152 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44153 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44155 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with ileostomy | X | |||

| 44156 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44160 | Colectomy with removal of terminal ileum and ileocolostomy | X | |||

| 44310 | Ileostomy or jejunostomy, nontube (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44320 | Colostomy or skin level cecostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44372 | Endoscopic placement of percutaneous jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44373 | Endoscopic conversion of percutaneous gastrostomy to jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 45110 | Proctectomy; complete, combined abdominoperineal, with colostomy | X | |||

| 45113 | Proctectomy, partial, with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 45119 | Proctectomy, combined abdominoperineal pull-through procedure (e.g., colo-anal anastomosis), with creation of colonic reservoir (e.g., J pouch), with or without proximal diverting ostomy | X | |||

| 56346 | Laparoscopy with gastrostomy placement | X | |||

| 56347 | Laparoscopy with jejunostomy placement | X | |||

| 74350 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement by a radiologist | X | |||

| 58960 | Laparotomy, for staging or restaging of ovarian malignancy (second look), with or without omentectomy, peritoneal washing, biopsy of abdominal and pelvic peritoneum, diaphragmatic assessment with pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 49000 | Exploratory laparotomy, exploratory celiotomy with or without biopsy(s) (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 56300 | Laparoscopy (peritoneoscopy), diagnostic | X | |||

| 56305 | Laparoscopy with biopsy | X | |||

| 56306 | Laparoscopy with aspiration | X |

| Procedure code(s) . | Description . | Cancer-directed surgery . | Second-look surgery . | Debulking . | Ostomy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 | |||||

| 65.2 | Wedge resection or partial excision of ovary | X | |||

| 65.3x | Unilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.4x | Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.5x | Bilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.6x | Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 68.8 | Pelvic evisceration | X | X | ||

| 43.1 | Gastrostomy, includes PEG (43.11) and other (43.19) | X | |||

| 46.32 | PEJ | X | |||

| 46.39 | Feeding jejunostomy | X | |||

| 46.0–46.24 | Colostomy or ileostomy | X | |||

| 54.1 | Laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.11 | Exploratory laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.21 | Laparoscopy | X | |||

| 68.3–68.7, 68.9 | Hysterectomy | X | |||

| CPT | |||||

| 56303 | Laparoscopy with excision of ovary or peritoneum | X | |||

| 56307 | Laparoscopic oophorectomy +/− salpingectomy | X | |||

| 56308 | Laparoscopy and vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 57531 | Para-aortic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58150 | TAH +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58152 | TAH with colpo-urethrocystopexy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58180 | Subtotal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58200 | TAH with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58210 | Radical hysterectomy | X | |||

| 58240 | Pelvic exenteration, including colostomy | X | X | ||

| 58262 | Vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58263 | Vaginal hysterectomy with repair of enterocele +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58720 | Salpingo-oophorectomy, complete or partial, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58920 | Wedge resection of ovary | X | |||

| 58940 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58943 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral; for ovarian malignancy, with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node biopsies, peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsies, diaphragmatic assessments, with or without salpingectomy(s), with or without omentectomy | X | |||

| 58950 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; | X | |||

| 58951 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with total abdominal hysterectomy, pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 58952 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with radical dissection for debulking | X | X | ||

| 43246 | Endoscopy with percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43750 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43760 | Change of gastrostomy tube | X | |||

| 43761 | Duodenal feeding tube | X | |||

| 43830 | Temporary gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43832 | Permanent gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 44015 | Surgical placement of jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44125 | Enterectomy, resection of small intestine; with enterostomy | X | |||

| 44130 | Enteroenterostomy, anastomosis of intestine, with or without cutaneous enterostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44141 | Colectomy, partial; with skin level cecostomy or colostomy | X | |||

| 44143 | Colectomy, partial; with end colostomy and closure of distal segment (Hartmann type procedure) | X | |||

| 44144 | Colectomy, partial; with resection, with colostomy or ileostomy and creation of mucofistula | X | |||

| 44146 | Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic anastomosis), with colostomy | X | |||

| 44150 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy | X | |||

| 44151 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44152 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44153 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44155 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with ileostomy | X | |||

| 44156 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44160 | Colectomy with removal of terminal ileum and ileocolostomy | X | |||

| 44310 | Ileostomy or jejunostomy, nontube (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44320 | Colostomy or skin level cecostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44372 | Endoscopic placement of percutaneous jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44373 | Endoscopic conversion of percutaneous gastrostomy to jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 45110 | Proctectomy; complete, combined abdominoperineal, with colostomy | X | |||

| 45113 | Proctectomy, partial, with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 45119 | Proctectomy, combined abdominoperineal pull-through procedure (e.g., colo-anal anastomosis), with creation of colonic reservoir (e.g., J pouch), with or without proximal diverting ostomy | X | |||

| 56346 | Laparoscopy with gastrostomy placement | X | |||

| 56347 | Laparoscopy with jejunostomy placement | X | |||

| 74350 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement by a radiologist | X | |||

| 58960 | Laparotomy, for staging or restaging of ovarian malignancy (second look), with or without omentectomy, peritoneal washing, biopsy of abdominal and pelvic peritoneum, diaphragmatic assessment with pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 49000 | Exploratory laparotomy, exploratory celiotomy with or without biopsy(s) (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 56300 | Laparoscopy (peritoneoscopy), diagnostic | X | |||

| 56305 | Laparoscopy with biopsy | X | |||

| 56306 | Laparoscopy with aspiration | X |

ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision; PEG = percutaneous (endoscopic) gastrostomy; PEJ = percutaneous (endoscopic) jejunostomy; CPT-4 = Current Procedural Terminology, 4th edition; +/− = with or without; TAH = total abdominal hysterectomy.

Billing codes for and classification of surgical procedures *

| Procedure code(s) . | Description . | Cancer-directed surgery . | Second-look surgery . | Debulking . | Ostomy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 | |||||

| 65.2 | Wedge resection or partial excision of ovary | X | |||

| 65.3x | Unilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.4x | Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.5x | Bilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.6x | Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 68.8 | Pelvic evisceration | X | X | ||

| 43.1 | Gastrostomy, includes PEG (43.11) and other (43.19) | X | |||

| 46.32 | PEJ | X | |||

| 46.39 | Feeding jejunostomy | X | |||

| 46.0–46.24 | Colostomy or ileostomy | X | |||

| 54.1 | Laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.11 | Exploratory laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.21 | Laparoscopy | X | |||

| 68.3–68.7, 68.9 | Hysterectomy | X | |||

| CPT | |||||

| 56303 | Laparoscopy with excision of ovary or peritoneum | X | |||

| 56307 | Laparoscopic oophorectomy +/− salpingectomy | X | |||

| 56308 | Laparoscopy and vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 57531 | Para-aortic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58150 | TAH +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58152 | TAH with colpo-urethrocystopexy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58180 | Subtotal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58200 | TAH with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58210 | Radical hysterectomy | X | |||

| 58240 | Pelvic exenteration, including colostomy | X | X | ||

| 58262 | Vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58263 | Vaginal hysterectomy with repair of enterocele +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58720 | Salpingo-oophorectomy, complete or partial, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58920 | Wedge resection of ovary | X | |||

| 58940 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58943 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral; for ovarian malignancy, with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node biopsies, peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsies, diaphragmatic assessments, with or without salpingectomy(s), with or without omentectomy | X | |||

| 58950 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; | X | |||

| 58951 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with total abdominal hysterectomy, pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 58952 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with radical dissection for debulking | X | X | ||

| 43246 | Endoscopy with percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43750 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43760 | Change of gastrostomy tube | X | |||

| 43761 | Duodenal feeding tube | X | |||

| 43830 | Temporary gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43832 | Permanent gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 44015 | Surgical placement of jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44125 | Enterectomy, resection of small intestine; with enterostomy | X | |||

| 44130 | Enteroenterostomy, anastomosis of intestine, with or without cutaneous enterostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44141 | Colectomy, partial; with skin level cecostomy or colostomy | X | |||

| 44143 | Colectomy, partial; with end colostomy and closure of distal segment (Hartmann type procedure) | X | |||

| 44144 | Colectomy, partial; with resection, with colostomy or ileostomy and creation of mucofistula | X | |||

| 44146 | Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic anastomosis), with colostomy | X | |||

| 44150 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy | X | |||

| 44151 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44152 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44153 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44155 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with ileostomy | X | |||

| 44156 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44160 | Colectomy with removal of terminal ileum and ileocolostomy | X | |||

| 44310 | Ileostomy or jejunostomy, nontube (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44320 | Colostomy or skin level cecostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44372 | Endoscopic placement of percutaneous jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44373 | Endoscopic conversion of percutaneous gastrostomy to jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 45110 | Proctectomy; complete, combined abdominoperineal, with colostomy | X | |||

| 45113 | Proctectomy, partial, with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 45119 | Proctectomy, combined abdominoperineal pull-through procedure (e.g., colo-anal anastomosis), with creation of colonic reservoir (e.g., J pouch), with or without proximal diverting ostomy | X | |||

| 56346 | Laparoscopy with gastrostomy placement | X | |||

| 56347 | Laparoscopy with jejunostomy placement | X | |||

| 74350 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement by a radiologist | X | |||

| 58960 | Laparotomy, for staging or restaging of ovarian malignancy (second look), with or without omentectomy, peritoneal washing, biopsy of abdominal and pelvic peritoneum, diaphragmatic assessment with pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 49000 | Exploratory laparotomy, exploratory celiotomy with or without biopsy(s) (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 56300 | Laparoscopy (peritoneoscopy), diagnostic | X | |||

| 56305 | Laparoscopy with biopsy | X | |||

| 56306 | Laparoscopy with aspiration | X |

| Procedure code(s) . | Description . | Cancer-directed surgery . | Second-look surgery . | Debulking . | Ostomy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 | |||||

| 65.2 | Wedge resection or partial excision of ovary | X | |||

| 65.3x | Unilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.4x | Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.5x | Bilateral oophorectomy | X | |||

| 65.6x | Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 68.8 | Pelvic evisceration | X | X | ||

| 43.1 | Gastrostomy, includes PEG (43.11) and other (43.19) | X | |||

| 46.32 | PEJ | X | |||

| 46.39 | Feeding jejunostomy | X | |||

| 46.0–46.24 | Colostomy or ileostomy | X | |||

| 54.1 | Laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.11 | Exploratory laparotomy | X | |||

| 54.21 | Laparoscopy | X | |||

| 68.3–68.7, 68.9 | Hysterectomy | X | |||

| CPT | |||||

| 56303 | Laparoscopy with excision of ovary or peritoneum | X | |||

| 56307 | Laparoscopic oophorectomy +/− salpingectomy | X | |||

| 56308 | Laparoscopy and vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 57531 | Para-aortic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58150 | TAH +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58152 | TAH with colpo-urethrocystopexy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58180 | Subtotal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58200 | TAH with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node sampling +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58210 | Radical hysterectomy | X | |||

| 58240 | Pelvic exenteration, including colostomy | X | X | ||

| 58262 | Vaginal hysterectomy +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58263 | Vaginal hysterectomy with repair of enterocele +/− salpingo-oophorectomy | X | |||

| 58720 | Salpingo-oophorectomy, complete or partial, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58920 | Wedge resection of ovary | X | |||

| 58940 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral | X | |||

| 58943 | Oophorectomy, partial or total, unilateral or bilateral; for ovarian malignancy, with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node biopsies, peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsies, diaphragmatic assessments, with or without salpingectomy(s), with or without omentectomy | X | |||

| 58950 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; | X | |||

| 58951 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with total abdominal hysterectomy, pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 58952 | Resection of ovarian malignancy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy; with radical dissection for debulking | X | X | ||

| 43246 | Endoscopy with percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43750 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43760 | Change of gastrostomy tube | X | |||

| 43761 | Duodenal feeding tube | X | |||

| 43830 | Temporary gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 43832 | Permanent gastrostomy tube placement | X | |||

| 44015 | Surgical placement of jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44125 | Enterectomy, resection of small intestine; with enterostomy | X | |||

| 44130 | Enteroenterostomy, anastomosis of intestine, with or without cutaneous enterostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44141 | Colectomy, partial; with skin level cecostomy or colostomy | X | |||

| 44143 | Colectomy, partial; with end colostomy and closure of distal segment (Hartmann type procedure) | X | |||

| 44144 | Colectomy, partial; with resection, with colostomy or ileostomy and creation of mucofistula | X | |||

| 44146 | Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic anastomosis), with colostomy | X | |||

| 44150 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy | X | |||

| 44151 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44152 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44153 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 44155 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with ileostomy | X | |||

| 44156 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, with proctectomy; with continent ileostomy | X | |||

| 44160 | Colectomy with removal of terminal ileum and ileocolostomy | X | |||

| 44310 | Ileostomy or jejunostomy, nontube (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44320 | Colostomy or skin level cecostomy (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 44372 | Endoscopic placement of percutaneous jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 44373 | Endoscopic conversion of percutaneous gastrostomy to jejunostomy tube | X | |||

| 45110 | Proctectomy; complete, combined abdominoperineal, with colostomy | X | |||

| 45113 | Proctectomy, partial, with rectal mucosectomy, ileoanal anastomosis, creation of ileal reservoir (S or J pouch), with or without loop ileostomy | X | |||

| 45119 | Proctectomy, combined abdominoperineal pull-through procedure (e.g., colo-anal anastomosis), with creation of colonic reservoir (e.g., J pouch), with or without proximal diverting ostomy | X | |||

| 56346 | Laparoscopy with gastrostomy placement | X | |||

| 56347 | Laparoscopy with jejunostomy placement | X | |||

| 74350 | Percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement by a radiologist | X | |||

| 58960 | Laparotomy, for staging or restaging of ovarian malignancy (second look), with or without omentectomy, peritoneal washing, biopsy of abdominal and pelvic peritoneum, diaphragmatic assessment with pelvic and limited para-aortic lymphadenectomy | X | |||

| 49000 | Exploratory laparotomy, exploratory celiotomy with or without biopsy(s) (separate procedure) | X | |||

| 56300 | Laparoscopy (peritoneoscopy), diagnostic | X | |||

| 56305 | Laparoscopy with biopsy | X | |||

| 56306 | Laparoscopy with aspiration | X |

ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision; PEG = percutaneous (endoscopic) gastrostomy; PEJ = percutaneous (endoscopic) jejunostomy; CPT-4 = Current Procedural Terminology, 4th edition; +/− = with or without; TAH = total abdominal hysterectomy.

Billing codes for complications and their timing *

| . | . | . | . | . | Rehospitalization diagnosis . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery-related complications . | ICD-9 diagnostic code(s) . | ICD-9 procedure code(s) . | CPT-4 code(s) . | Index stay . | Primary . | Any . | |

| Wound infection | |||||||

| Postoperative infection | 998.5x | 10140, 10160, 10180 | X | X | |||

| Persistent postoperative fistula | 998.6 | X | X | ||||

| Debridement of abdominal wound | 54.3, 54.0 | 49002 | X | X | |||

| Incision and drainage of abscess | 10060, 10061, 45000, 47300, 49020, 49021, 49040, 49041, 49060, 49061 | X | X | ||||

| Abscess of intestine | 569.5 | X | X | ||||

| Vascular intestinal insufficiency | 557 | X | X | ||||

| Abdominal wall wound complication | 879.3, 879.5 | X | X | ||||

| Bowel obstruction | 560.1, 560.81, 560.9, 997.4, 560.89 | X | X | ||||

| Reopening laparotomy for complication | 54.12 | X | X | ||||

| Drainage of intra-abdominal abscess or hematoma | 54.19 | X | X | ||||

| Pulmonary embolus/deep venous thrombosis | |||||||

| Pulmonary embolus | 415.1–415.19 | X | X | ||||

| Deep venous thrombosis | 451–451.19, 451.2, 453.8, 997.2, 999.2 | X | X | ||||

| Hematoma/hemorrhage | |||||||

| Hematoma | 998.1x | X | X | ||||

| Aspiration of hematoma | 86.01 | 10140, 10141, 10160 | X | X | |||

| Hemorrhage | 459.0, 578.9 | 39.98 | 35840 | X | X | ||

| Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage | 578.9 | X | X | ||||

| Blood transfusion | 99.03, 99.04 | 36430 | X | X | |||

| Other surgical complications | |||||||

| Wound dehiscence | 998.3 | 54.61 | 12020,12021, 13160 | X | X | ||

| Peritonitis | 567.xx | 00752 | X | X | |||

| Perforation | 998.2, 569.83, E870.0 | X | X | ||||

| Repair of intestine | 46.7 | X | X | ||||

| Surgical complications not otherwise specified | 998.9 | X | X | ||||

| Injury to vessels of abdomen and pelvis | 902.x | X | X | ||||

| Suture of laceration of ureter | 56.82 | X | X | ||||

| Foreign body | 998.4, 998.7x, E871, E781.0 | 49085 | X | X | |||

| Other | 998.89, 989.9, E872.0, E874.0, E876.2, E876.3, E876.5, E876.4, E878.6 | X | X | ||||

| Stoma complications | 519.00. 519.09, 569.60-69,997.4 | X | X | ||||

| Cardiac | |||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 410.xx | 92975 | |||||

| Congestive heart failure/pulmonary edema | 428.xx, 402.01, 402.11, 518.4, 514 | X | X | ||||

| Cardiac arrest | 427.5 | 92950, 92953, 92960 | X | X | |||

| Cardiac arrest/failure resulting from a procedure | 997.1 | X | X | ||||

| Venticular tachycardia | 427.4 | X | X | ||||

| Circulatory monitoring (via central catheter) | 89.61–89.69 | ||||||

| Respiratory | X | X | |||||

| Collapsed lung/pneumothorax | 512.1, 518.0 | 32002 | X | X | |||

| Respiratory failure/arrest | 518.81,799.1 | 31500 | X | X | |||

| Respiratory complications | 997.3 | X | X | ||||

| Respiratory distress/insufficiency | 518.82, 518.5 | X | X | ||||

| Nonoperative intubation | 96.01–96.05 | X | X | ||||

| Stroke | 433.xx, 434.xx, 436, 437.1 | X | X | ||||

| Acute renal failure | 584.xx, 586 | X | X | ||||

| Shock | |||||||

| Postoperative shock | 998.0 | X | |||||

| Shock | 785.5x | X | |||||

| Anaphylactic shock | 995.0, 995.4 | X | |||||

| Hypotension | 458.0, 458.9, 958.4 | X | |||||

| Fluid/electrolyte imbalances | |||||||

| Nausea and vomiting | 787–787.03, 536.2 | X | X | ||||

| Dehydration | 276.5 | X | X | ||||

| Hyponatremia | 276.1 | X | X | ||||

| General infections | |||||||

| Pneumonia/respiratory infection | 480–486 | X | X | ||||

| Sepsis/bacteremia | 038–038.9, 790.7 | X | X | ||||

| Urinary tract infection | 599 | X | X | ||||

| Clostridium difficile | 00845 | X | X | ||||

| Other bacterial organisms | 041.xx | X | X | ||||

| Contaminated blood/fluid/drug | E875 | X | X | ||||

| Toxic reactions to medicine | E930–E947 | X | X | ||||

| . | . | . | . | . | Rehospitalization diagnosis . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery-related complications . | ICD-9 diagnostic code(s) . | ICD-9 procedure code(s) . | CPT-4 code(s) . | Index stay . | Primary . | Any . | |

| Wound infection | |||||||

| Postoperative infection | 998.5x | 10140, 10160, 10180 | X | X | |||

| Persistent postoperative fistula | 998.6 | X | X | ||||

| Debridement of abdominal wound | 54.3, 54.0 | 49002 | X | X | |||

| Incision and drainage of abscess | 10060, 10061, 45000, 47300, 49020, 49021, 49040, 49041, 49060, 49061 | X | X | ||||

| Abscess of intestine | 569.5 | X | X | ||||

| Vascular intestinal insufficiency | 557 | X | X | ||||

| Abdominal wall wound complication | 879.3, 879.5 | X | X | ||||

| Bowel obstruction | 560.1, 560.81, 560.9, 997.4, 560.89 | X | X | ||||

| Reopening laparotomy for complication | 54.12 | X | X | ||||

| Drainage of intra-abdominal abscess or hematoma | 54.19 | X | X | ||||

| Pulmonary embolus/deep venous thrombosis | |||||||

| Pulmonary embolus | 415.1–415.19 | X | X | ||||

| Deep venous thrombosis | 451–451.19, 451.2, 453.8, 997.2, 999.2 | X | X | ||||

| Hematoma/hemorrhage | |||||||

| Hematoma | 998.1x | X | X | ||||

| Aspiration of hematoma | 86.01 | 10140, 10141, 10160 | X | X | |||

| Hemorrhage | 459.0, 578.9 | 39.98 | 35840 | X | X | ||

| Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage | 578.9 | X | X | ||||

| Blood transfusion | 99.03, 99.04 | 36430 | X | X | |||

| Other surgical complications | |||||||

| Wound dehiscence | 998.3 | 54.61 | 12020,12021, 13160 | X | X | ||

| Peritonitis | 567.xx | 00752 | X | X | |||

| Perforation | 998.2, 569.83, E870.0 | X | X | ||||

| Repair of intestine | 46.7 | X | X | ||||

| Surgical complications not otherwise specified | 998.9 | X | X | ||||

| Injury to vessels of abdomen and pelvis | 902.x | X | X | ||||

| Suture of laceration of ureter | 56.82 | X | X | ||||

| Foreign body | 998.4, 998.7x, E871, E781.0 | 49085 | X | X | |||

| Other | 998.89, 989.9, E872.0, E874.0, E876.2, E876.3, E876.5, E876.4, E878.6 | X | X | ||||

| Stoma complications | 519.00. 519.09, 569.60-69,997.4 | X | X | ||||

| Cardiac | |||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 410.xx | 92975 | |||||

| Congestive heart failure/pulmonary edema | 428.xx, 402.01, 402.11, 518.4, 514 | X | X | ||||

| Cardiac arrest | 427.5 | 92950, 92953, 92960 | X | X | |||

| Cardiac arrest/failure resulting from a procedure | 997.1 | X | X | ||||

| Venticular tachycardia | 427.4 | X | X | ||||

| Circulatory monitoring (via central catheter) | 89.61–89.69 | ||||||

| Respiratory | X | X | |||||

| Collapsed lung/pneumothorax | 512.1, 518.0 | 32002 | X | X | |||

| Respiratory failure/arrest | 518.81,799.1 | 31500 | X | X | |||

| Respiratory complications | 997.3 | X | X | ||||

| Respiratory distress/insufficiency | 518.82, 518.5 | X | X | ||||

| Nonoperative intubation | 96.01–96.05 | X | X | ||||

| Stroke | 433.xx, 434.xx, 436, 437.1 | X | X | ||||

| Acute renal failure | 584.xx, 586 | X | X | ||||

| Shock | |||||||

| Postoperative shock | 998.0 | X | |||||

| Shock | 785.5x | X | |||||

| Anaphylactic shock | 995.0, 995.4 | X | |||||

| Hypotension | 458.0, 458.9, 958.4 | X | |||||

| Fluid/electrolyte imbalances | |||||||

| Nausea and vomiting | 787–787.03, 536.2 | X | X | ||||

| Dehydration | 276.5 | X | X | ||||