-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pontus Naucler, Walter Ryd, Sven Törnberg, Anders Strand, Göran Wadell, Kristina Elfgren, Thomas Rådberg, Björn Strander, Ola Forslund, Bengt-Göran Hansson, Björn Hagmar, Bo Johansson, Eva Rylander, Joakim Dillner, Efficacy of HPV DNA Testing With Cytology Triage and/or Repeat HPV DNA Testing in Primary Cervical Cancer Screening, JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Volume 101, Issue 2, 21 January 2009, Pages 88–99, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn444

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Primary cervical screening with both human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing and cytological examination of cervical cells with a Pap test (cytology) has been evaluated in randomized clinical trials. Because the vast majority of women with positive cytology are also HPV DNA positive, screening strategies that use HPV DNA testing as the primary screening test may be more effective.

We used the database from the intervention arm (n = 6257 women) of a population-based randomized trial of double screening with cytology and HPV DNA testing to evaluate the efficacy of 11 possible cervical screening strategies that are based on HPV DNA testing alone, cytology alone, and HPV DNA testing combined with cytology among women aged 32–38 years. The main outcome measures were sensitivity for detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse (CIN3+) within 6 months of enrollment or at colposcopy for women with a persistent type-specific HPV infection and the number of screening tests and positive predictive value (PPV) for each screening strategy. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Compared with screening by cytology alone, double testing with cytology and for type-specific HPV persistence resulted in a 35% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 15% to 60%) increase in sensitivity to detect CIN3+, without a statistically significant reduction in the PPV (relative PPV = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.52 to 1.10), but with more than twice as many screening tests needed. Several strategies that incorporated screening for high-risk HPV subtypes were explored, but they resulted in reduced PPV compared with cytology. Compared with cytology, primary screening with HPV DNA testing followed by cytological triage and repeat HPV DNA testing of HPV DNA–positive women with normal cytology increased the CIN3+ sensitivity by 30% (95% CI = 9% to 54%), maintained a high PPV (relative PPV = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.60 to 1.26), and resulted in a mere 12% increase in the number of screening tests (from 6257 to 7019 tests).

Primary HPV DNA–based screening with cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA testing of cytology-negative women appears to be the most feasible cervical screening strategy.

Data from randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA–based primary cervical screening with that of screening by cytology for the prevention of cervical cancer indicate that the former has higher sensitivity than the latter (ie, it detects more high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions) but lower specificity, raising concerns that HPV DNA–based primary screening could lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up for many women. Alternative combinations of cytology and HPV DNA testing–based screening strategies may have greater specificity than those tested in these trials.

Data from the intervention arm of a randomized trial of HPV DNA testing as an add-on to primary cervical cancer screening by cytology were used to explore the efficacy of 11 different screening strategies based on HPV DNA testing alone, cytology alone, and HPV DNA testing combined with cytology.

Primary HPV DNA testing followed by triaging with cytology and screening for persistent HPV type-specific infection had a considerably higher sensitivity for detecting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse than screening by cytology alone and led to only a modest increase in the number of screening tests and referrals.

Using HPV DNA testing as primary screening followed by cytological triage and repeat HPV DNA testing of women with normal cytology who are HPV DNA positive after at least 1 year is a feasible strategy in primary cervical screening.

The study population was limited to women aged 32–38 years. Not all women in the cohort were referred to colposcopy.

From the Editors

Primary cervical cancer screening by cytological examination of cervical cells with a Pap test has reduced the incidence of cervical cancer in countries with organized screening programs ( 1 , 2 ). However, several studies have shown that cytology has a limited sensitivity for detecting high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), the precursor of cervical cancer ( 3 , 4 ). Infection with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV) is the major cause of cervical cancer ( 5 , 6 ), and several cross-sectional studies ( 4 , 7 , 8 ) have reported that HPV DNA testing is more sensitive than cytology in detecting high-grade CIN. Thus far, in most countries that screen for cervical cancer, including the United States, HPV DNA testing has been used as a triage test for women who have a cytological diagnosis of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) ( 9 , 10 ). In the United States, HPV DNA testing has also been accepted as an adjunct to cytology in primary screening for women aged 30 years or older on the basis of results from cohort studies ( 11 , 12 ). Several randomized controlled trials have been conducted to compare the efficacy of HPV DNA–based primary screening with that of screening by cytology for the detection of cervical cancer ( 4 , 13–18 ). Data from these trials indicate that HPV DNA–based screening has higher sensitivity than cytology-based screening (ie, it detects more high-grade CIN lesions) but lower specificity ( 4 , 13 , 15–18 ). The lower specificity of HPV DNA–based testing compared with cytology in primary screening has raised concerns that HPV DNA–based screening will lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up for many women ( 16 ). However, it is possible that alternative screening strategies that combine cytology and HPV DNA testing may have greater specificity than those tested in these trials ( 15 , 17 , 18 ).

We used data from the intervention arm of Swedescreen ( 16 , 19 ), a randomized trial in Sweden of HPV DNA testing as an add-on to primary cervical cancer screening by cytology, to explore the efficacy of 11 different screening strategies that are based on HPV DNA testing alone, cytology alone, and HPV DNA testing combined with cytology.

Subjects and Methods

Study Design

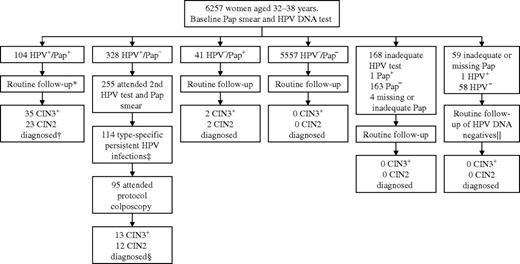

Swedescreen is a population-based randomized controlled trial of HPV DNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening that was conducted within the Swedish organized screening program from 1997 through 2005. The structure of the trial has been described in detail elsewhere ( 16 , 19 ). In brief, women aged 32–38 years who lived in one of five Swedish cities (Stockholm, Uppsala, Malmö, Umeå, or Gothenburg) and had taken part in the organized Swedish cervical cancer screening program between May 1997 and December 2000 were invited to participate in Swedescreen. A total of 12 527 women gave verbal consent to participate in the study; each of these women had baseline cervical samples taken with a cytological brush. The brush was first used to prepare a Pap smear and was then swirled in 1 mL of sterile 0.9% sodium chloride to release the remaining cells, which were then frozen. The women were then randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention arm (in which a Pap smear and HPV DNA testing were performed on the baseline screening samples; n = 6257 women) or the control arm (in which only a Pap smear was performed, and the frozen samples were stored for future use; n = 6270 women). Random assignment was conducted by an independent institute (the Cancer Registry of Stockholm) using computer-generated random numbers. The primary aim of the trial was to investigate if screening with cytology in combination with screening for persistent type-specific HPV infection reduced the incidence of high-grade CIN compared with cytology alone ( 16 ). A secondary aim of the trial, and the subject of this report, was to investigate the cross-sectional efficacy of HPV DNA testing, cytology, and combinations of the two in the detection of CIN grade 2 or worse [CIN2+, defined as CIN grade 2 (CIN2) or CIN grade 3 (CIN3), adenocarcinoma in situ or invasive cervical cancer ( 20 )]. We did not include women from the control arm of the randomized trial in this analysis because only women with abnormal cytology were followed up in the control arm ( 16 ). All of the 6257 women who were randomly assigned to the intervention arm were included in this analysis ( Figure 1 ). Women with abnormal Pap smears were followed up according to regional routine practices. For example, in Stockholm, all women with an abnormal Pap smear (defined as ASCUS or a more severe cytological diagnosis) were immediately referred for a routine colposcopy. For women in Uppsala, Malmö, Umeå, and Gothenburg, a repeat Pap smear was an option in cases of ASCUS or CIN grade 1 (CIN1). Cytological diagnoses followed the older North American system described by Koss ( 20 ). A Pap smear with koilocytosis but no other cytological changes was considered abnormal cytology in Umeå and Gothenburg and normal cytology in Stockholm, Uppsala, and Malmö. Women in the intervention arm who had normal cytology and a positive HPV DNA test at enrollment were invited to undergo a second cervical HPV DNA test and Pap smear at least 1 year after enrollment ( Figure 1 ). Women who were found to be persistently positive for the same HPV type at the second HPV DNA test were invited to undergo a study protocol–defined colposcopy. The exact number of women who did not attend follow-up as well as all protocol violations are reported in detail elsewhere ( 16 ).

Flowchart of the screening profiles of women in the intervention arm of the Swedescreen trial. The study protocol specified that human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA–positive women with normal cytology would be invited for a second HPV DNA test and Pap smear at least 1 year after enrollment followed by colposcopy of women with persistent HPV type-specific infection. *A total of 14 women had a second HPV DNA test and Pap smear and five women with type-specific persistent HPV infection attended the protocol colposcopy (protocol violation). †In all, 55 CIN2+ lesions were diagnosed at routine follow-up and three CIN2+ lesions were diagnosed at protocol colposcopy. ‡A total of 139 women had negative HPV DNA test or change of HPV type, and two women had an inadequate HPV DNA test. §No CIN2+ lesions were diagnosed among women who did not attend the protocol colposcopy. ‖One woman with positive HPV DNA test at enrollment had a negative second HPV DNA test. Pap + = a Pap smear with a cytological diagnosis of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or worse; Pap − = normal Pap smear; HPV + = positive HPV DNA test; HPV − = negative HPV DNA test; CIN2 = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2; CIN3 = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3; CIN3+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse.

At the study protocol–defined colposcopy, ectocervical biopsy specimens were taken from all lesions that were white after acetic acid application or iodine negative. If the colposcopy was normal (ie, no such lesions were seen), two biopsy specimens were taken at the 12-o’clock and 6-o’clock positions on the ectocervix, close to the squamocolumnar cell junction and subjected to histopathologic analysis. Both the women and the clinical personnel were unaware of the results of HPV DNA testing and cytology for women who were referred to the protocol colposcopy. All women were followed up by linkage with regional cytology and pathology registries as well as with the national cytology registry using the unique personal identification numbers that are assigned to all Swedish residents. These registries contain data on all Pap smears and biopsy specimens taken in Sweden, both within and outside of the organized screening program. Histological samples with abnormal diagnoses that were taken outside the study protocol as well as all biopsy specimens taken at the protocol-defined colposcopies were reevaluated by an expert pathologist (W. Ryd) who was unaware of the HPV DNA status and randomization status of the women. When the diagnosis on reevaluation differed from the original diagnosis by more than one level of severity (eg, CIN3 instead of CIN1), the diagnosis was adjudicated by a second expert pathologist (Dr Ann-Mari Jakobsen, Department of Pathology and Clinical Cytology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden), who was also unaware of the HPV DNA and random assignment status of the women. The expert-rereviewed diagnoses were used as the final diagnoses in this analysis. When the archival specimens could not be located, the original diagnoses were used.

The Swedescreen study was approved by the ethics board of the Karolinska Institute, which specified the consent procedure, in which all participants gave verbal consent after having received written information. The Swedescreen trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT00479375.

HPV DNA Testing

All frozen cervical cell samples from women in the intervention arm were thawed and tested for HPV DNA with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based enzyme immunoassay in which HPV DNA was detected by amplification of a part of the L1 gene of HPV using GP5+ and GP6+ general PCR primer s, followed by hybridization with a cocktail with type-specific probes for the high-risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68 ( 21 , 22 ). Cut-point criteria for positivity were defined before the start of the study ( 21 , 22 ). The human β- globin ( HBB ) gene was amplified in parallel in a separate PCR assay to assess the DNA quality of the specimen ( 22 ). An analysis for the 14 individual HPV types was performed by reverse dot blot hybridization using recombinant type-specific HPV plasmids on all HPV PCR–positive samples, as previously described ( 23 ). In cases where the reverse dot blot hybridization was negative (no hybridization visible), the HPV type was determined by cloning and DNA sequencing. Only samples that were confirmed to be positive for any of the 14 high-risk types by reverse dot blot hybridization or DNA sequence analysis were classified as HPV DNA positive.

Statistical Analysis

All histologically verified cases of CIN2+ detected within 6 months after Swedescreen trial enrollment or at the protocol colposcopy performed on women with a persistent type-specific HPV infection were included in this cross-sectional analysis. Women who did not have a CIN2+ lesion recorded in the registries as well as women who had not had a biopsy or a colposcopy performed were classified as women who did not have a high-grade CIN lesion. Women who had a cytological diagnosis of ASCUS or worse (ie, ASCUS, atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance [AGUS], CIN1, CIN2, CIN3, invasive cancer, or adenocarcinoma in situ) were classified as having abnormal cytology. This cutoff was chosen so that our results would be comparable with those of other studies ( 4 , 13–15 , 17 ) even though koilocytosis as an ancillary diagnosis in normal smears had been classified as abnormal cytology warranting follow-up in two of the cities (Umeå and Gothenburg).

We evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of HPV DNA testing and cytology among women who had adequate HPV DNA and cytology tests at baseline. Separate analyses were performed using histologically confirmed CIN2+ and histologically confirmed CIN3 or worse (ie, CIN3+) as endpoints. We compared the efficacy—defined as the sensitivity (proportion of CIN2+ or CIN3+ detected), PPV, and the number of screening tests required—of 10 different screening strategies involving HPV DNA testing with that of primary screening with cytology only. The PPV describes the proportion of test-positive women who actually have the disease being screened for. We used the total number of screening tests and the number of tests needed to detect one case of CIN2+ and CIN3+ as indicators of the cost-effectiveness of a screening strategy. We considered the following screening strategies: 1) a single HPV DNA test; 2) an HPV DNA test in combination with cytology (either as the primary test or as triage); 3) screening for persistent type-specific HPV infection; and 4) screening for specific high-risk HPV types. We explored two different strategies to screen for specific high-risk HPV types: testing for HPV types 16, 31, and 33, which were previously found to confer a higher risk for future CIN2+ than other HPV types in this population ( 24 ), and testing for HPV types 16 and 18, which in other cohort studies ( 25 , 26 ) were found to confer a particularly high risk for the development of CIN3+. All proportions were calculated with exact 95% binominal confidence intervals (CIs). We compared the efficacy of different screening strategies by calculating risk ratios with 95% confidence interval.

We performed sensitivity analyses to account for 1) the impact of nonattending women (ie, HPV DNA–positive women with normal cytology who did not have a second HPV test, women with persistent type-specific HPV infections who did not have a colposcopy, and women with a cytological diagnosis of ASCUS or worse who did not have a follow-up biopsy recorded in the pathological registries within 6 months after enrollment) and 2) the impact of women who had inadequate or missing screening tests at enrollment. The observed probabilities of CIN2+ among women with adequate screening tests and of having positive or negative screening tests among women with adequate test results were calculated and used to estimate the risk of CIN2+ among nonattending women and women with missing or inadequate screening tests. In these sensitivity analyses, we considered several scenarios, including ones in which we assumed that nonattending women had the same or higher risk of CIN2+ compared with women who attended screening, and that women with inadequate or missing screening test results had the same or higher risk of having a positive HPV DNA test or cytology than that observed among women with adequate test results ( 27 ).

The Swedescreen trial had a power of 80%, at a statistical significance level of .05, to detect at least a 50% decrease in the incidence of CIN2+ during the next screening round, assuming that the 3-year cumulative incidence of CIN2+ among women in this age group was 1.0% ( 16 ). This study was able to estimate a relative sensitivity to detect CIN3+ of primary HPV screening compared with cytology of 1.30 with a 95% CI of 1.09 to 1.54 and relative PPV of 0.44 with a 95% CI of 0.30 to 0.64 (power estimated using the delta method) ( 28 ). All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Of the 6257 women assigned to the intervention arm of Swedescreen and included in this analysis, 6194 (99.0%) had an adequate baseline Pap smear recorded in the cytology registries ( Table 1 , Figure 1 ). Among women with adequate Pap smears, 146 (2.3%) had a cytological diagnosis of ASCUS or worse. Of the 6257 women included in this analysis, 6089 (97.3%) had an adequate HPV DNA test at enrollment (defined as positive for PCR amplification of the HBB gene), and 7.1% of these women were HPV DNA positive. The prevalence of HPV DNA increased with increasing cytological severity, from 5.4% in women with normal cytology to 86.5% in women with CIN2+ ( Ptrend < .001).

Results of baseline cytology and HPV DNA testing *

| Cytology result | HPV DNA test result † | Total ‡ | ||

| Positive | Negative | Inadequate | ||

| Missing § | 1 (2.9) | 31 (88.6) | 3 (8.6) | 35 (0.6) |

| Unsatisfactory smear | 0 (0) | 27 (96.4) | 1 (3.6) | 28 (0.4) |

| Normal ‖ | 328 (5.4) | 5557 (91.9) | 163 (2.7) | 6048 (96.7) |

| Atypia ¶ | 49 (63.6) | 27 (35.1) | 1 (1.3) | 77 (1.2) |

| CIN1 | 23 (71.9) | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.5) |

| CIN2+ # | 32 (86.5) | 5 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.6) |

| Total | 433 (6.9) | 5656 (90.4) | 168 (2.7) | 6257 |

| Cytology result | HPV DNA test result † | Total ‡ | ||

| Positive | Negative | Inadequate | ||

| Missing § | 1 (2.9) | 31 (88.6) | 3 (8.6) | 35 (0.6) |

| Unsatisfactory smear | 0 (0) | 27 (96.4) | 1 (3.6) | 28 (0.4) |

| Normal ‖ | 328 (5.4) | 5557 (91.9) | 163 (2.7) | 6048 (96.7) |

| Atypia ¶ | 49 (63.6) | 27 (35.1) | 1 (1.3) | 77 (1.2) |

| CIN1 | 23 (71.9) | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.5) |

| CIN2+ # | 32 (86.5) | 5 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.6) |

| Total | 433 (6.9) | 5656 (90.4) | 168 (2.7) | 6257 |

Data are presented as the number of test results (%). HPV = human papillomavirus; CIN1 = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse.

Percentages are for row totals.

Percentages are for column total.

The baseline Pap smear could not be found in cytological and pathological registries.

Includes benign Pap smears and benign Pap smears with koilocytosis.

Includes atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance and atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. The diagnosis (atypical squamous cells—cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion) was not used in Sweden at the time of the study.

Includes CIN2, CIN3, suspected invasive cancers, and adenocarcinoma in situ.

Results of baseline cytology and HPV DNA testing *

| Cytology result | HPV DNA test result † | Total ‡ | ||

| Positive | Negative | Inadequate | ||

| Missing § | 1 (2.9) | 31 (88.6) | 3 (8.6) | 35 (0.6) |

| Unsatisfactory smear | 0 (0) | 27 (96.4) | 1 (3.6) | 28 (0.4) |

| Normal ‖ | 328 (5.4) | 5557 (91.9) | 163 (2.7) | 6048 (96.7) |

| Atypia ¶ | 49 (63.6) | 27 (35.1) | 1 (1.3) | 77 (1.2) |

| CIN1 | 23 (71.9) | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.5) |

| CIN2+ # | 32 (86.5) | 5 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.6) |

| Total | 433 (6.9) | 5656 (90.4) | 168 (2.7) | 6257 |

| Cytology result | HPV DNA test result † | Total ‡ | ||

| Positive | Negative | Inadequate | ||

| Missing § | 1 (2.9) | 31 (88.6) | 3 (8.6) | 35 (0.6) |

| Unsatisfactory smear | 0 (0) | 27 (96.4) | 1 (3.6) | 28 (0.4) |

| Normal ‖ | 328 (5.4) | 5557 (91.9) | 163 (2.7) | 6048 (96.7) |

| Atypia ¶ | 49 (63.6) | 27 (35.1) | 1 (1.3) | 77 (1.2) |

| CIN1 | 23 (71.9) | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.5) |

| CIN2+ # | 32 (86.5) | 5 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.6) |

| Total | 433 (6.9) | 5656 (90.4) | 168 (2.7) | 6257 |

Data are presented as the number of test results (%). HPV = human papillomavirus; CIN1 = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse.

Percentages are for row totals.

Percentages are for column total.

The baseline Pap smear could not be found in cytological and pathological registries.

Includes benign Pap smears and benign Pap smears with koilocytosis.

Includes atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance and atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. The diagnosis (atypical squamous cells—cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion) was not used in Sweden at the time of the study.

Includes CIN2, CIN3, suspected invasive cancers, and adenocarcinoma in situ.

Of the 87 CIN2+ diagnoses, 37 were CIN2, 50 were CIN3+, and 81 were based on histopathologic rereview. Table 2 presents the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of cytology and HPV DNA testing for histologically confirmed CIN2+ and CIN3+. The sensitivity of HPV DNA testing for detecting CIN3+ was 96.0% (95% CI = 86.3% to 99.5%), whereas the sensitivity of cytology was 74.0% (95% CI = 59.7% to 85.4%). With CIN3+ as the endpoint, the specificity of cytology was 98.2% (95% CI = 97.9% to 98.5%) and that of HPV testing was 93.6% (95% CI = 93.0% to 94.2%). The PPV of cytology for CIN3+ was 25.3% (95% CI = 18.5% to 33.2%), and the PPV of HPV DNA testing for CIN3+ was 11.1% (95% CI = 8.3% to 14.4%). The NPV of HPV DNA testing for CIN3+ was 99.96% (95% CI = 99.87% to 100.0%), and the PPV of cytology for CIN3+ was 99.79% (95% CI = 99.63% to 99.89%). There was no substantial change in the sensitivity, specificity, or NPV of HPV DNA testing or cytology when CIN2+ was the endpoint. However, the PPVs of cytology and HPV DNA testing for CIN2+ increased to 42.5% (95% CI = 34.3% to 50.9%) and 19.2% (95% CI = 15.6% to 23.2%), respectively.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of cytology and HPV DNA test *

| Endpoint | Screening test † | No. of women who were screening test positive/No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | No. of women who were screening test negative/No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint | Specificity, % (95% CI) | No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis/No. of women who were screening test positive | PPV, % (95% CI) | No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint/No. of women who were screening test negative | NPV, % (95% CI) |

| CIN2+ | Cytology | 62/87 | 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 6023/6107 | 98.6 (98.3 to 98.9) | 62/146 | 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 6023/6048 | 99.59 (99.39 to 99.73) |

| HPV DNA test | 83/87 | 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 5652/6002 | 94.2 (93.5 to 94.7) | 83/433 | 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 5652/5656 | 99.93 (99.82 to 99.98) | |

| CIN3+ | Cytology | 37/50 | 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 6035/6144 | 98.2 (97.9 to 98.5) | 37/146 | 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 6035/6048 | 99.79 (99.63 to 99.89) |

| HPV DNA test | 48/50 | 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 5654/6039 | 93.6 (93.0 to 94.2) | 48/433 | 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 5654/5656 | 99.96 (99.87 to 100.0) |

| Endpoint | Screening test † | No. of women who were screening test positive/No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | No. of women who were screening test negative/No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint | Specificity, % (95% CI) | No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis/No. of women who were screening test positive | PPV, % (95% CI) | No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint/No. of women who were screening test negative | NPV, % (95% CI) |

| CIN2+ | Cytology | 62/87 | 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 6023/6107 | 98.6 (98.3 to 98.9) | 62/146 | 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 6023/6048 | 99.59 (99.39 to 99.73) |

| HPV DNA test | 83/87 | 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 5652/6002 | 94.2 (93.5 to 94.7) | 83/433 | 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 5652/5656 | 99.93 (99.82 to 99.98) | |

| CIN3+ | Cytology | 37/50 | 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 6035/6144 | 98.2 (97.9 to 98.5) | 37/146 | 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 6035/6048 | 99.79 (99.63 to 99.89) |

| HPV DNA test | 48/50 | 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 5654/6039 | 93.6 (93.0 to 94.2) | 48/433 | 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 5654/5656 | 99.96 (99.87 to 100.0) |

Includes women with adequate screening tests at baseline. CI = confidence interval; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; CIN3+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse; and HPV = human papillomavirus.

Cytology cutoff for test positivity: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or worse (ie, atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance; grade 1, 2, or 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; and suspected invasive cancers and adenocarcinoma in situ).

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of cytology and HPV DNA test *

| Endpoint | Screening test † | No. of women who were screening test positive/No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | No. of women who were screening test negative/No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint | Specificity, % (95% CI) | No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis/No. of women who were screening test positive | PPV, % (95% CI) | No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint/No. of women who were screening test negative | NPV, % (95% CI) |

| CIN2+ | Cytology | 62/87 | 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 6023/6107 | 98.6 (98.3 to 98.9) | 62/146 | 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 6023/6048 | 99.59 (99.39 to 99.73) |

| HPV DNA test | 83/87 | 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 5652/6002 | 94.2 (93.5 to 94.7) | 83/433 | 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 5652/5656 | 99.93 (99.82 to 99.98) | |

| CIN3+ | Cytology | 37/50 | 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 6035/6144 | 98.2 (97.9 to 98.5) | 37/146 | 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 6035/6048 | 99.79 (99.63 to 99.89) |

| HPV DNA test | 48/50 | 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 5654/6039 | 93.6 (93.0 to 94.2) | 48/433 | 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 5654/5656 | 99.96 (99.87 to 100.0) |

| Endpoint | Screening test † | No. of women who were screening test positive/No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | No. of women who were screening test negative/No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint | Specificity, % (95% CI) | No. of women with histology-verified diagnosis/No. of women who were screening test positive | PPV, % (95% CI) | No. of women with no histological confirmation or a negative histological endpoint/No. of women who were screening test negative | NPV, % (95% CI) |

| CIN2+ | Cytology | 62/87 | 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 6023/6107 | 98.6 (98.3 to 98.9) | 62/146 | 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 6023/6048 | 99.59 (99.39 to 99.73) |

| HPV DNA test | 83/87 | 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 5652/6002 | 94.2 (93.5 to 94.7) | 83/433 | 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 5652/5656 | 99.93 (99.82 to 99.98) | |

| CIN3+ | Cytology | 37/50 | 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 6035/6144 | 98.2 (97.9 to 98.5) | 37/146 | 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 6035/6048 | 99.79 (99.63 to 99.89) |

| HPV DNA test | 48/50 | 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 5654/6039 | 93.6 (93.0 to 94.2) | 48/433 | 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 5654/5656 | 99.96 (99.87 to 100.0) |

Includes women with adequate screening tests at baseline. CI = confidence interval; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; CIN3+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse; and HPV = human papillomavirus.

Cytology cutoff for test positivity: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or worse (ie, atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance; grade 1, 2, or 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; and suspected invasive cancers and adenocarcinoma in situ).

We next compared the sensitivity and PPV of different HPV DNA–based screening strategies for detecting CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions with that of screening by cytology only ( Table 3 ). Compared with screening by cytology only, cytological screening in combination with HPV DNA screening for persistent type-specific HPV infection (ie, the screening strategy used in the intervention arm of the Swedescreen trial according to the study protocol) resulted in a 40% increase (95% CI = 23% to 60%) in the sensitivity to detect CIN2+ lesions and 35% increase (95% CI = 15% to 60%) in the sensitivity to detect CIN3+ lesions without a statistically significant decrease in the PPV (relative PPV = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.52 to 1.10) ( Table 3 ). However, this screening strategy resulted in 105% more screening tests performed (defined as either an HPV DNA test or a Pap smear) compared with cytology only (12 839 vs 6257 tests), and 46% and 52% more screening tests per detected case of CIN2+ and CIN3+, respectively, compared with cytology alone. By contrast, compared with cytology alone, screening by a single HPV DNA test did not increase the total number of tests performed and reduced the number of screening tests needed to detect one case of CIN2+ and one case of CIN3+ by 25% and 23%, respectively. In addition, compared with cytology alone, screening by a single HPV DNA test increased the sensitivity of detecting CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions by 34% (95% CI = 16% to 54%) and 30% (95% CI = 9% to 54%), respectively, but decreased the PPV by 55% (95% CI = 41% to 76%) and 56% (95% CI = 36% to 70%), respectively. Compared with cytology, a strategy based on primary screening with HPV DNA testing followed by cytological triage and retesting of HPV DNA–positive women with normal cytology to screen for type-specific HPV persistence at least 1 year later resulted in a 34% increase (95% CI = 16% to 54%) in the sensitivity to detect CIN2+ lesions and a 30% increase (95% CI = 9% to 54%) increase in the sensitivity to detect CIN3+ lesions without decreasing the PPVs (eg, relative PPV for CIN3+ = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.60 to 1.26) and only marginally increased the total number of tests that were performed from 6257 to 7019 (a 12% increase). Compared with cytology, this strategy also reduced the number of screening tests required per detected case of CIN2+ or CIN3+ by 16% and 14%, respectively.

Sensitivity and PPV of different HPV DNA–based screening strategies compared with primary screening by cytology only *

| Screening strategy † | Endpoint CIN2+ | Endpoint CIN3+ | Total no. of tests used ‖ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN2+ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN3+ | ||||||

| Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||||

| Cytology only | 62/87, 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 1.00 (referent) | 62/146, 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/50, 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/146, 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 1.00 (referent) | 6257 | 100.9 | 169.1 |

| HPV DNA test only | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/433, 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/433, 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 0.44 (0.30 to 0.64) | 6257 | 75.4 | 130.4 |

| Cytology and HPV DNA test | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/475, 18.3 (14.9 to 22.1) | 0.43 (0.33 to 0.56) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/475, 10.5 (7.9 to 13.6) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.61) | 12 514 | 143.8 | 250.3 |

| HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology ¶ | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/218, 38.1 (31.6 to 44.9) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/218, 22.0 (16.7 to 28.1) | 0.87 (0.60 to 1.26) | 7019 | 84.6 | 146.2 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 only | 60/87, 69.0 (58.1 to 78.5) | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.18) | 60/231, 26.0 (20.4 to 32.1) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.82) | 35/50, 70.0 (55.4 to 82.1) | 0.95 (74.1 to 1.21) | 35/231, 15.2 (10.8 to 20.4) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.90) | 6257 | 104.3 | 178.8 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 only | 44/87, 50.6 (39.6 to 61.5) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.91) | 44/175, 25.1 (18.9 to 32.2) | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.81) | 28/50, 56.0 (41.3 to 70.0) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.02) | 28/175, 16.0 (10.9 to 22.3) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98) | 6257 | 142.2 | 223.5 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology ** | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/312, 26.6 (21.8 to 31.9) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.82) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/312, 15.4 (11.6 to 19.9) | 0.61 (0.41 to 0.89) | 6619 | 79.7 | 137.9 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology †† | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/294, 28.2 (23.2 to 33.7) | 0.66 (0.51 to 86.4) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/294, 16.3 (12.3 to 21.1) | 0.64 (0.44 to 0.94) | 6719 | 81.0 | 140.0 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 among women with normal cytology ‡‡ | 81/87, 93.1 (85.6 to 97.4) | 1.31 (1.13 to 1.51) | 81/315, 25.7 (21.0 to 30.9) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.79) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/315, 15.3 (11.5 to 19.7) | 0.60 (0.41 to 0.88) | 12 368 | 152.7 | 257.7 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 among women with normal cytology §§ | 72/87, 82.8 (73.2 to 90.0) | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.39) | 72/270, 26.7 (21.5 to 32.4) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.83) | 41/50, 82.0 (68.6 to 91.4) | 1.11 (89.9 to 1.37) | 41/270, 15.2 (11.1 to 20.0) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.89) | 12 368 | 171.8 | 301.7 |

| Cytology and screening for persistent type-specific HPV infection ‖‖ | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/260, 33.5 (27.8 to 39.6) | 0.79 (0.61 to 1.02) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/260, 19.2 (14.6 to 24.6) | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.10) | 12 839 | 147.6 | 256.9 |

| Screening strategy † | Endpoint CIN2+ | Endpoint CIN3+ | Total no. of tests used ‖ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN2+ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN3+ | ||||||

| Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||||

| Cytology only | 62/87, 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 1.00 (referent) | 62/146, 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/50, 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/146, 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 1.00 (referent) | 6257 | 100.9 | 169.1 |

| HPV DNA test only | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/433, 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/433, 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 0.44 (0.30 to 0.64) | 6257 | 75.4 | 130.4 |

| Cytology and HPV DNA test | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/475, 18.3 (14.9 to 22.1) | 0.43 (0.33 to 0.56) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/475, 10.5 (7.9 to 13.6) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.61) | 12 514 | 143.8 | 250.3 |

| HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology ¶ | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/218, 38.1 (31.6 to 44.9) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/218, 22.0 (16.7 to 28.1) | 0.87 (0.60 to 1.26) | 7019 | 84.6 | 146.2 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 only | 60/87, 69.0 (58.1 to 78.5) | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.18) | 60/231, 26.0 (20.4 to 32.1) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.82) | 35/50, 70.0 (55.4 to 82.1) | 0.95 (74.1 to 1.21) | 35/231, 15.2 (10.8 to 20.4) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.90) | 6257 | 104.3 | 178.8 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 only | 44/87, 50.6 (39.6 to 61.5) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.91) | 44/175, 25.1 (18.9 to 32.2) | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.81) | 28/50, 56.0 (41.3 to 70.0) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.02) | 28/175, 16.0 (10.9 to 22.3) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98) | 6257 | 142.2 | 223.5 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology ** | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/312, 26.6 (21.8 to 31.9) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.82) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/312, 15.4 (11.6 to 19.9) | 0.61 (0.41 to 0.89) | 6619 | 79.7 | 137.9 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology †† | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/294, 28.2 (23.2 to 33.7) | 0.66 (0.51 to 86.4) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/294, 16.3 (12.3 to 21.1) | 0.64 (0.44 to 0.94) | 6719 | 81.0 | 140.0 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 among women with normal cytology ‡‡ | 81/87, 93.1 (85.6 to 97.4) | 1.31 (1.13 to 1.51) | 81/315, 25.7 (21.0 to 30.9) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.79) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/315, 15.3 (11.5 to 19.7) | 0.60 (0.41 to 0.88) | 12 368 | 152.7 | 257.7 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 among women with normal cytology §§ | 72/87, 82.8 (73.2 to 90.0) | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.39) | 72/270, 26.7 (21.5 to 32.4) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.83) | 41/50, 82.0 (68.6 to 91.4) | 1.11 (89.9 to 1.37) | 41/270, 15.2 (11.1 to 20.0) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.89) | 12 368 | 171.8 | 301.7 |

| Cytology and screening for persistent type-specific HPV infection ‖‖ | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/260, 33.5 (27.8 to 39.6) | 0.79 (0.61 to 1.02) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/260, 19.2 (14.6 to 24.6) | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.10) | 12 839 | 147.6 | 256.9 |

Includes women with adequate screening tests at baseline. HPV = human papillomavirus; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; CIN3+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse; and CI = confidence interval.

Cytology cutoff for test positivity: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or worse (ie, atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance; grade 1, 2, or 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; and suspected invasive cancers and adenocarcinoma in situ).

Sensitivity is given by the number of women who were screening test positive/the number of all women with histology-verified diagnosis and as a percentage (with 95% confidence interval).

PPV is given by the number of women with histology-verified diagnosis/the number of all women who were screening test positive and as a percentage (with 95% confidence interval).

Excludes colposcopies.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: HPV DNA positive with abnormal cytology or normal cytology and persistent type-specific HPV infection.

Assumes an HPV DNA test that includes typing for 14 different oncogenic HPV types, where the typing data determine if there should be immediate referral or cytological triage/repeat testing.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: positive for HPV type 16, 31, or 33 DNA or HPV DNA positive for other types with abnormal cytology in triage or normal cytology in triage but persistent type-specific HPV infection.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: positive for HPV 16 or 18 DNA or HPV DNA positive for other types for women with abnormal cytology in triage or normal cytology in triage but persistent type-specific HPV infection.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: abnormal cytology or positive for HPV 16, 31, or 33 DNA.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: abnormal cytology or positive for HPV 16 or 18 DNA.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: abnormal cytology or normal cytology and persistent type-specific HPV infection (per trial protocol).

Sensitivity and PPV of different HPV DNA–based screening strategies compared with primary screening by cytology only *

| Screening strategy † | Endpoint CIN2+ | Endpoint CIN3+ | Total no. of tests used ‖ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN2+ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN3+ | ||||||

| Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||||

| Cytology only | 62/87, 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 1.00 (referent) | 62/146, 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/50, 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/146, 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 1.00 (referent) | 6257 | 100.9 | 169.1 |

| HPV DNA test only | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/433, 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/433, 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 0.44 (0.30 to 0.64) | 6257 | 75.4 | 130.4 |

| Cytology and HPV DNA test | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/475, 18.3 (14.9 to 22.1) | 0.43 (0.33 to 0.56) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/475, 10.5 (7.9 to 13.6) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.61) | 12 514 | 143.8 | 250.3 |

| HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology ¶ | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/218, 38.1 (31.6 to 44.9) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/218, 22.0 (16.7 to 28.1) | 0.87 (0.60 to 1.26) | 7019 | 84.6 | 146.2 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 only | 60/87, 69.0 (58.1 to 78.5) | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.18) | 60/231, 26.0 (20.4 to 32.1) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.82) | 35/50, 70.0 (55.4 to 82.1) | 0.95 (74.1 to 1.21) | 35/231, 15.2 (10.8 to 20.4) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.90) | 6257 | 104.3 | 178.8 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 only | 44/87, 50.6 (39.6 to 61.5) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.91) | 44/175, 25.1 (18.9 to 32.2) | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.81) | 28/50, 56.0 (41.3 to 70.0) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.02) | 28/175, 16.0 (10.9 to 22.3) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98) | 6257 | 142.2 | 223.5 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology ** | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/312, 26.6 (21.8 to 31.9) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.82) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/312, 15.4 (11.6 to 19.9) | 0.61 (0.41 to 0.89) | 6619 | 79.7 | 137.9 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology †† | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/294, 28.2 (23.2 to 33.7) | 0.66 (0.51 to 86.4) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/294, 16.3 (12.3 to 21.1) | 0.64 (0.44 to 0.94) | 6719 | 81.0 | 140.0 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 among women with normal cytology ‡‡ | 81/87, 93.1 (85.6 to 97.4) | 1.31 (1.13 to 1.51) | 81/315, 25.7 (21.0 to 30.9) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.79) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/315, 15.3 (11.5 to 19.7) | 0.60 (0.41 to 0.88) | 12 368 | 152.7 | 257.7 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 among women with normal cytology §§ | 72/87, 82.8 (73.2 to 90.0) | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.39) | 72/270, 26.7 (21.5 to 32.4) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.83) | 41/50, 82.0 (68.6 to 91.4) | 1.11 (89.9 to 1.37) | 41/270, 15.2 (11.1 to 20.0) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.89) | 12 368 | 171.8 | 301.7 |

| Cytology and screening for persistent type-specific HPV infection ‖‖ | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/260, 33.5 (27.8 to 39.6) | 0.79 (0.61 to 1.02) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/260, 19.2 (14.6 to 24.6) | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.10) | 12 839 | 147.6 | 256.9 |

| Screening strategy † | Endpoint CIN2+ | Endpoint CIN3+ | Total no. of tests used ‖ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN2+ | No. of screening tests required to detect one case of CIN3+ | ||||||

| Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity ‡ , % (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | PPV § , % (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||||

| Cytology only | 62/87, 71.3 (60.6 to 80.5) | 1.00 (referent) | 62/146, 42.5 (34.3 to 50.9) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/50, 74.0 (59.7 to 85.4) | 1.00 (referent) | 37/146, 25.3 (18.5 to 33.2) | 1.00 (referent) | 6257 | 100.9 | 169.1 |

| HPV DNA test only | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/433, 19.2 (15.6 to 23.2) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/433, 11.1 (8.3 to 14.4) | 0.44 (0.30 to 0.64) | 6257 | 75.4 | 130.4 |

| Cytology and HPV DNA test | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/475, 18.3 (14.9 to 22.1) | 0.43 (0.33 to 0.56) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/475, 10.5 (7.9 to 13.6) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.61) | 12 514 | 143.8 | 250.3 |

| HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology ¶ | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/218, 38.1 (31.6 to 44.9) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/218, 22.0 (16.7 to 28.1) | 0.87 (0.60 to 1.26) | 7019 | 84.6 | 146.2 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 only | 60/87, 69.0 (58.1 to 78.5) | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.18) | 60/231, 26.0 (20.4 to 32.1) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.82) | 35/50, 70.0 (55.4 to 82.1) | 0.95 (74.1 to 1.21) | 35/231, 15.2 (10.8 to 20.4) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.90) | 6257 | 104.3 | 178.8 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 only | 44/87, 50.6 (39.6 to 61.5) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.91) | 44/175, 25.1 (18.9 to 32.2) | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.81) | 28/50, 56.0 (41.3 to 70.0) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.02) | 28/175, 16.0 (10.9 to 22.3) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98) | 6257 | 142.2 | 223.5 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology ** | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/312, 26.6 (21.8 to 31.9) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.82) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/312, 15.4 (11.6 to 19.9) | 0.61 (0.41 to 0.89) | 6619 | 79.7 | 137.9 |

| HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18, cytology triage of positives for other HPV types and repeat HPV DNA test # if normal cytology †† | 83/87, 95.4 (88.6 to 98.7) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 83/294, 28.2 (23.2 to 33.7) | 0.66 (0.51 to 86.4) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/294, 16.3 (12.3 to 21.1) | 0.64 (0.44 to 0.94) | 6719 | 81.0 | 140.0 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16, 31, and 33 among women with normal cytology ‡‡ | 81/87, 93.1 (85.6 to 97.4) | 1.31 (1.13 to 1.51) | 81/315, 25.7 (21.0 to 30.9) | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.79) | 48/50, 96.0 (86.3 to 99.5) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.54) | 48/315, 15.3 (11.5 to 19.7) | 0.60 (0.41 to 0.88) | 12 368 | 152.7 | 257.7 |

| Cytology followed by HPV DNA test targeting types 16 and 18 among women with normal cytology §§ | 72/87, 82.8 (73.2 to 90.0) | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.39) | 72/270, 26.7 (21.5 to 32.4) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.83) | 41/50, 82.0 (68.6 to 91.4) | 1.11 (89.9 to 1.37) | 41/270, 15.2 (11.1 to 20.0) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.89) | 12 368 | 171.8 | 301.7 |

| Cytology and screening for persistent type-specific HPV infection ‖‖ | 87/87, 100 (95.8 to 100.0) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.60) | 87/260, 33.5 (27.8 to 39.6) | 0.79 (0.61 to 1.02) | 50/50, 100 (92.9 to 100.0) | 1.35 (1.15 to 1.60) | 50/260, 19.2 (14.6 to 24.6) | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.10) | 12 839 | 147.6 | 256.9 |

Includes women with adequate screening tests at baseline. HPV = human papillomavirus; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; CIN3+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse; and CI = confidence interval.

Cytology cutoff for test positivity: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or worse (ie, atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance; grade 1, 2, or 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; and suspected invasive cancers and adenocarcinoma in situ).

Sensitivity is given by the number of women who were screening test positive/the number of all women with histology-verified diagnosis and as a percentage (with 95% confidence interval).

PPV is given by the number of women with histology-verified diagnosis/the number of all women who were screening test positive and as a percentage (with 95% confidence interval).

Excludes colposcopies.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: HPV DNA positive with abnormal cytology or normal cytology and persistent type-specific HPV infection.

Assumes an HPV DNA test that includes typing for 14 different oncogenic HPV types, where the typing data determine if there should be immediate referral or cytological triage/repeat testing.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: positive for HPV type 16, 31, or 33 DNA or HPV DNA positive for other types with abnormal cytology in triage or normal cytology in triage but persistent type-specific HPV infection.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: positive for HPV 16 or 18 DNA or HPV DNA positive for other types for women with abnormal cytology in triage or normal cytology in triage but persistent type-specific HPV infection.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: abnormal cytology or positive for HPV 16, 31, or 33 DNA.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: abnormal cytology or positive for HPV 16 or 18 DNA.

Criteria for referral to colposcopy: abnormal cytology or normal cytology and persistent type-specific HPV infection (per trial protocol).

There was no difference between screening with cytology only and primary screening for HPV types 16, 31, and 33 in the sensitivity of detecting CIN2+ or CIN3+ lesions; however, the PPVs for primary screening for HPV types 16, 31, and 33 were decreased (relative PPV for CIN2+ = 0.61 [95% CI = 0.46 to 0.82]; relative PPV for CIN3+ = 0.60 [95% CI = 0.40 to 0.90]).

Compared with screening by cytology only, screening for HPV 16, 31, and 33 with cytological triage of women who were infected with HPV types other than HPV 16, 31, and 33 and repeat HPV DNA testing for HPV DNA–positive women with normal cytology resulted in a 34% increase (95% CI = 16% to 54%) in the sensitivity to detect CIN2+ and 30% increase (95% CI = 9% to 54%) in the sensitivity to detect CIN3+ lesions; however, the PPVs remained lower compared with cytological screening (relative PPV for CIN2+ = 0.63 [95% CI = 0.48 to 0.82]; relative PPV for CIN3+ = 0.61 [95% CI = 0.41 to 0.89]).

Compared with cytology alone, primary screening for HPV 16 and 18 resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the sensitivity to detect CIN2+ (relative sensitivity = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.55 to 0.91) and a reduction in the PPVs for both CIN2+ and CIN3+ (relative PPVs: 0.59 [95% CI = 0.43 to 0.81] and 0.63 [95% CI = 0.41 to 0.98], respectively) ( Table 3 ).

Compared with screening with cytology only, screening for HPV 16 and 18 with cytological triage of women who were infected with HPV types other than HPV 16 and 18 and repeat HPV DNA testing for HPV DNA–positive women with normal cytology resulted in increased sensitivity to detect both CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions but a decrease in the PPVs. Primary cytology screening followed by screening for HPV types 16 and 18 or for HPV types 16, 31, and 33 in women with normal cytology both resulted in statistically significantly reduced PPVs compared with cytology screening only ( Table 3 ).

We next performed a stratified analysis to investigate whether the length of time between HPV DNA testing at enrollment and the protocol colposcopy influenced the CIN2+ detection rate. The median time between the first HPV DNA test at enrollment and the second HPV DNA test was 1.64 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 1.24–2.32 years), and the median time between enrollment and the protocol colposcopy was 2.05 years (IQR = 1.55–2.86 years) ( Figure 1 ). A total of 14 CIN2+ lesions were detected at colposcopies performed up to 2.05 years after enrollment, and 14 CIN2+ lesions were detected at colposcopies performed after 2.05 years after enrollment ( P = 1.00). All of the high-grade lesions detected during routine follow-up of abnormal cytology were detected within 6 months of enrollment. Because some women with mildly abnormal cytology were not immediately referred to colposcopy but followed by repeat cytology, the resulting delay in CIN2+ detection could bias the results in favor of HPV DNA testing. To investigate this potential bias, we performed a separate analysis with an extended follow-up time that included all lesions detected within 2 years of enrollment or at the protocol colposcopies that were performed on women with a persistent HPV type-specific infection (a total of 98 CIN2+ and 58 CIN3+ lesions were detected). With the extended follow-up time, the sensitivity of cytology to detect CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions was slightly reduced from 71.3% (95% CI = 60.6% to 80.5%) to 69.4% (95% CI = 59.3% to 78.3%) and from 74.0% (95% CI = 59.7% to 85.4%) to 72.4% (95% CI = 59.1% to 83.3%), respectively. With the extended follow-up time, the PPV of cytology to detect CIN2+ and CIN3+ increased from 42.5% (95% CI = 34.3% to 50.9%) to 46.6% (95% CI = 38.3% to 55.0%) and from 25.3% (95% CI = 18.5% to 33.2%) to 28.8% (95% CI = 21.6% to 36.8%), respectively.

The frequency of inadequate tests was higher for HPV DNA testing than for cytology (2.7% vs 0.4%; P < .001). However, the frequency of inadequate HPV DNA tests was much lower for the second HPV DNA test than for the first HPV DNA test (0.1% vs 2.7%; P = .01).

There were eight women with koilocytosis in otherwise-benign Pap smears, five of whom were HPV DNA positive. None of them had any repeated testing within 6 months after enrollment. Seven of the women had repeated testing more than 6 months after enrollment: five had benign Pap smears and two had abnormal Pap smears that were followed by a biopsy (one woman had CIN2 and one had koilocytosis).

We next examined the impact of nonattendance to follow-up testing. Of the 328 HPV DNA–positive women who had normal Pap smears, 73 (22.3%) did not attend the second HPV DNA test and Pap smear, and 19 (16.7%) of 114 women with a persistent HPV type-specific infection did not attend the protocol colposcopy ( Figure 1 ). There was also nonattendance in the routine practice follow-up of abnormal cytology, where the likelihood of a woman having a biopsy specimen taken during routine follow-up appeared to depend on the severity of her baseline cytology: 53 (68.8%) of 77 women with ASCUS or AGUS, 25 (78.1%) of 32 women with CIN1, and 32 (86.5%) of 37 women with CIN2+ in cytology had a cervical biopsy result in the pathology registries within 6 months of enrollment ( Ptrend = .06). We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of nonattending women on the relative sensitivities of primary HPV DNA screening and primary HPV DNA screening followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV testing compared with primary cytology screening only. In the most extreme scenarios we tested (ie, when we assumed that nonattending women had a probability of having a CIN2+ lesion that was three times higher than that observed among attending women), the estimates of relative sensitivity were 1.27 and 1.78, respectively) ( Table 4 ). The assumption of differential CIN2+ risk in relation to attendance status also had limited influence on the relative PPV estimates ( Table 4 ). Inadequate or missing screening results at enrollment had little effect on the relative sensitivity and relative PPV ( Table 4 ).

Sensitivity analysis of impact of nonattendance and inadequate or missing enrollment screening tests on the relative sensitivity and relative PPV *

| Analysis | Screening with HPV DNA test vs cytology | Screening with HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology vs cytology | |||

| Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||

| Primary analysis | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | |

| Impact of nonattendance † | |||||

| Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with persistent type-specific HPV infection (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with abnormal cytology (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | ||||

| 1:1 | 1:1 | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.60) | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) |

| 2:1 | 1:1 | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.67) | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) |

| 3:1 | 1:1 | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 0.60 (0.48 to 0.75) | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) |

| 1:1 | 2:1 | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.44 (0.36 to 0.55) | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.76 (0.63 to 0.92) |

| 1:1 | 3:1 | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.43 (0.34 to 0.53) | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.89) |

| Impact of missing or inadequate enrollment screening test results | |||||

| Probability ratio of positive screening tests in women with inadequate or missing screening tests at enrollment to that in women with adequate tests at enrollment (the actual observed probability of positive screening tests) † | |||||

| 1:1 | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.14) | |

| 2:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.88 (1.69 to 1.14) | |

| 3:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.57) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13) | |

| Analysis | Screening with HPV DNA test vs cytology | Screening with HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology vs cytology | |||

| Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||

| Primary analysis | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | |

| Impact of nonattendance † | |||||

| Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with persistent type-specific HPV infection (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with abnormal cytology (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | ||||

| 1:1 | 1:1 | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.60) | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) |

| 2:1 | 1:1 | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.67) | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) |

| 3:1 | 1:1 | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 0.60 (0.48 to 0.75) | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) |

| 1:1 | 2:1 | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.44 (0.36 to 0.55) | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.76 (0.63 to 0.92) |

| 1:1 | 3:1 | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.43 (0.34 to 0.53) | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.89) |

| Impact of missing or inadequate enrollment screening test results | |||||

| Probability ratio of positive screening tests in women with inadequate or missing screening tests at enrollment to that in women with adequate tests at enrollment (the actual observed probability of positive screening tests) † | |||||

| 1:1 | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.14) | |

| 2:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.88 (1.69 to 1.14) | |

| 3:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.57) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13) | |

HPV = human papillomavirus; CI = confidence interval; PPV = positive predictive value; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse.

The observed probability of CIN2+ among women with adequate screening tests was used in these calculations.

Sensitivity analysis of impact of nonattendance and inadequate or missing enrollment screening tests on the relative sensitivity and relative PPV *

| Analysis | Screening with HPV DNA test vs cytology | Screening with HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology vs cytology | |||

| Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||

| Primary analysis | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | |

| Impact of nonattendance † | |||||

| Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with persistent type-specific HPV infection (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with abnormal cytology (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | ||||

| 1:1 | 1:1 | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.60) | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) |

| 2:1 | 1:1 | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.67) | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) |

| 3:1 | 1:1 | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 0.60 (0.48 to 0.75) | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) |

| 1:1 | 2:1 | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.44 (0.36 to 0.55) | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.76 (0.63 to 0.92) |

| 1:1 | 3:1 | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.43 (0.34 to 0.53) | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.89) |

| Impact of missing or inadequate enrollment screening test results | |||||

| Probability ratio of positive screening tests in women with inadequate or missing screening tests at enrollment to that in women with adequate tests at enrollment (the actual observed probability of positive screening tests) † | |||||

| 1:1 | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.14) | |

| 2:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.88 (1.69 to 1.14) | |

| 3:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.57) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13) | |

| Analysis | Screening with HPV DNA test vs cytology | Screening with HPV DNA test followed by cytology triage and repeat HPV DNA test if normal cytology vs cytology | |||

| Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | Relative sensitivity (95% CI) | Relative PPV (95% CI) | ||

| Primary analysis | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.54) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | |

| Impact of nonattendance † | |||||

| Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with persistent type-specific HPV infection (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | Probability ratio of CIN2+ in nonattending women to that in attending women with abnormal cytology (the actual observed probability of CIN2+) | ||||

| 1:1 | 1:1 | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.60) | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.63) | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) |

| 2:1 | 1:1 | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.67) | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) |

| 3:1 | 1:1 | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 0.60 (0.48 to 0.75) | 1.78 (1.51 to 2.10) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) |

| 1:1 | 2:1 | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.44 (0.36 to 0.55) | 1.31 (1.14 to 1.51) | 0.76 (0.63 to 0.92) |

| 1:1 | 3:1 | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.43 (0.34 to 0.53) | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.45) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.89) |

| Impact of missing or inadequate enrollment screening test results | |||||

| Probability ratio of positive screening tests in women with inadequate or missing screening tests at enrollment to that in women with adequate tests at enrollment (the actual observed probability of positive screening tests) † | |||||

| 1:1 | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.55) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.14) | |

| 2:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.58) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.56) | 0.88 (1.69 to 1.14) | |

| 3:1 | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.57) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13) | |

HPV = human papillomavirus; CI = confidence interval; PPV = positive predictive value; CIN2+ = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse.

The observed probability of CIN2+ among women with adequate screening tests was used in these calculations.

Discussion

We found that a cervical cancer screening strategy consisting of primary HPV DNA testing followed by triaging with cytology and screening for persistent HPV type-specific infection had a considerably higher sensitivity for detecting CIN3+ than screening by cytology alone and led to only a modest increase in the number of screening tests and referrals. The large size of the Swedescreen trial and the fact that it was nested within the population-based national cervical screening program suggest that our results are robust and generalizable to organized cervical screening for women in their mid-thirties (ie, the age group included in the trial).

A major concern regarding the use of HPV DNA tests in primary cervical cancer screening has been their lower specificity compared with cytology ( 13–18 ), which results in more women needing to go through unnecessary follow-up procedures, including repeat testing and colposcopy. As reported in other randomized ( 4 , 15 , 17 , 18 ) and nonrandomized ( 7 , 8 ) screening studies, we found that a one-time HPV DNA test has a lower specificity and PPV than cytology, for both CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions. By contrast, the screening strategy used in the intervention arm of the Swedish trial—cytological screening in combination with screening for persistent HPV type-specific infection—resulted in an increased sensitivity to detect CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions compared with screening with cytology alone without a statistically significant decrease in the PPV. However, this screening strategy was costly because more than twice the number of screening tests had to be performed compared with cytology alone. Our post hoc analyses of the efficacy of different HPV DNA–based screening strategies in combination with cytology indicate that the most effective screening strategy was primary screening with an HPV DNA test (the test used in this trial included HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) followed by cytological triage and rescreening for persistent HPV type-specific infection at least 1 year later among women with normal cytology. This screening strategy resulted in an increased sensitivity to detect CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions and maintained a high PPV and the number of screening tests performed increased by only 12% compared with conventional screening by cytology. Results of the HPV in Addition to Routine Testing study ( 29 ) also suggest that this strategy is safe. In that study, HPV DNA–positive women with normal cytology were randomly assigned to receive immediate colposcopy or to repeat HPV DNA testing and cytology 1 year later. The detection rates of CIN2+ were similar in the different randomization arms of the trial, and no CIN2+ lesion was found among women who had cleared their HPV infection.

Our study has limitations. First, our study population was limited to women aged 32–38 years. Because transient HPV infections are more common among younger women than among older women, it has been proposed that primary screening with HPV DNA testing should be restricted to women aged 30 years or older ( 12 ). A randomized controlled trial among Italian women aged 25–34 years reported that primary screening with HPV DNA testing followed by cytological triage and repeat testing of HPV DNA–positive women resulted in a 58% increase in sensitivity (95% CI = 3% to 144%) to detect CIN2+ compared with screening by cytology alone without a statistically significant decrease in the PPV (relative PPV = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.52 to 1.16) ( 17 ), suggesting that primary screening with HPV DNA testing followed by cytology triage and screening for persistent HPV infection is also feasible among women younger than 35 years of age. However, more studies are needed to determine the optimal screening strategies and psychosocial impact of primary HPV DNA screening among younger women.

Second, women who were negative in both cytology and HPV DNA testing, women who had cleared their HPV infection and were HPV DNA negative on repeat testing, as well as some women with a mild cytological abnormality who were followed up with repeat cytology were not referred to colposcopy. Because not all women in the cohort were referred to colposcopy, our data represent relative rather than absolute measurements of sensitivity and specificity. However, a number of colposcopies performed at random in the control arm of the Swedescreen trial that included taking of biopsies for histopathology also in case of normal colposcopy found little cervical disease, which suggests that nonreferral of cytology-negative and HPV DNA–negative women induced limited verification bias ( 19 ).

Third, our study was nested within the routine organized screening program in Sweden, which uses the older North American cytological diagnostic system and does not consistently refer women with koilocytosis to colposcopy. According to the Bethesda cytology system ( 30 ) that is used in the United States, koilocytotic atypia is classified as a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion that triggers referral to colposcopy. A formal exchange of reference slides between expert cytopathologists participating in Scandinavian and US studies showed that Scandinavian cytopathologists tend to rate slides as normal more frequently than US cytopathologists ( 31 ). However, there were only eight women with koilocytosis in otherwise-normal smears in our cohort, seven of whom were followed up. Because there was only a single case of CIN2 diagnosed among these women, it is likely that lowering the threshold of cytological classification to always refer women with koilocytosis would have only marginally improved the sensitivity of cytology.

Fourth, some women who were referred to follow-up testing or colposcopy did not attend these tests, and some baseline cytology and HPV DNA tests were inadequate. However, a sensitivity analysis of the effects of these limitations found our results to be robust, given that even extreme scenarios of differential CIN2+ rates according to compliance had only a modest impact on the results.

Fifth, there was a protocol violation in that 14 HPV DNA–positive women with abnormal cytology had a repeat HPV DNA test and five of these women also had a protocol colposcopy. However, this protocol violation is unlikely to have had a negative impact on the sensitivity or PPV of cytology because these women were subjected to additional assessment compared with that normally scheduled for women with normal cytology.

A sixth limitation is the length of follow-up time, which was shorter for women with abnormal cytology than for women with persistent HPV infection. This difference could have biased the data in favor of HPV DNA testing, in particular because follow-up with repeat cytology was an option among women who had mildly abnormal cytology. However, extending the follow-up time from 6 months to 2 years did not improve the sensitivity of cytology.

Finally, the fact that we used conventional cytology rather than modern liquid-based cytology could be considered a limitation. Liquid-based cytology facilitates the logistics of screening because the same cervical sample can be used for both cytology and HPV DNA testing. However, our study also used this split-sample design, that is, for each woman, we used one cervical sample to prepare a Pap smear and to obtain cells for HPV DNA testing. Although there is conflicting evidence regarding the efficacy of liquid-based cytology at detecting high-grade CIN compared with that of conventional cytology, a meta-analysis ( 32 ) of all studies in which subjects were referred to colposcopy with biopsy found that liquid-based cytology did not increase the sensitivity or specificity for CIN2+ compared with conventional cytology, although it reduced the number of inadequate samples. However, a randomized trial that was published later ( 33 ) reported increased detection of CIN2+ with liquid-based cytology compared with conventional cytology. Liquid-based cytology would simplify the logistics of HPV DNA testing with cytological triage, the screening strategy that in this study was found to have the most favorable combination of high sensitivity for CIN2+, high PPV, and low number of screening tests required.

Our identification of HPV DNA screening with cytology triage as the most feasible screening strategy is at variance with results of a Canadian randomized controlled trial that argued in favor of primary HPV DNA screening only because subsequent cytological triage reduced the sensitivity to detect CIN2+ lesions from 97.4% to 57.8% ( 4 ). However, the reduced sensitivity was balanced by a greatly reduced colposcopy referral rate (from 6.1% to 1.1% with cytological triage compared with HPV DNA testing only). In addition, the Canadian study did not include screening for persistent HPV infection among women who had normal cytology ( 4 ).

An Italian HPV screening trial reported that combined cytology and HPV DNA screening resulted in an increased detection of CIN2+ lesions (relative sensitivity = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.03 to 2.09) but a lower PPV (relative PPV = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.23 to 0.66) compared with screening with cytology only ( 18 ). HPV DNA testing alone resulted in a relative sensitivity of 1.43 (95% CI = 1.00 to 2.04) and relative PPV of 0.58 (95% CI = 0.33 to 0.98) compared with cytology ( 18 ). A Finnish trial of women aged 30–60 years who were randomly assigned to HPV DNA testing followed by cytology triage of HPV DNA–positive women or conventional screening with cytology alone found that screening with an HPV DNA test alone resulted in a statistically significantly reduced specificity and PPV compared with cytology alone, whereas HPV DNA testing with cytology triage had a specificity and PPV similar to that of screening with cytology alone ( 15 ). In our trial, our post hoc analysis of screening with an HPV DNA test alone or with both an HPV DNA test and cytology at baseline resulted in an increased sensitivity to detect both CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions but a reduced PPV compared with screening with cytology only, indicating that repeated testing—either as screening for persistent HPV infection or as cytological triage of HPV DNA–positive women—is needed within an HPV DNA–based screening program to reduce the number of false positives.

Our finding that cytology had a lower sensitivity than HPV DNA testing for detecting CIN2+ and CIN3+ lesions (approximately 70%–75% vs approximately 95%, respectively) is consistent with results from other randomized and nonrandomized studies ( 4 , 7 , 8 , 17 , 18 ), which have shown that in developed countries, the sensitivity of HPV DNA testing for detecting CIN2+ lesions is consistently approximately 95%, whereas the sensitivity of cytology for detecting CIN2+ is highly variable depending on geographical location and the age group being screened.

The baseline prevalences of HPV DNA positivity (7.1%) and of cytological diagnosis of ASCUS or worse (2.3%) in the Swedescreen trial were similar to those in most other randomized controlled trials of HPV DNA testing. In an Italian trial of women aged 35–60 years ( 18 ), a Finnish trial of women aged 30–60 years ( 15 ), a Canadian trial of women aged 30–69 years ( 4 ), and a Dutch trial of women aged 29–56 years ( 34 ), the HPV prevalence ranged from 4.5% to 9.3% and the prevalence of women with abnormal cytology (ie, ASCUS or worse [except for the Finnish trial, which excluded women with ASCUS]) ranged from 1.0% to 3.6%. Hence, our results are likely to be generalizable to screening programs in several other countries. A randomized trial in England had a markedly higher prevalence of abnormal cytology than the other trials (12% among women aged 30–49 years) ( 14 ). In such settings, that is, where the cytology that is used has a high prevalence of abnormal findings, screening strategies that are based on HPV DNA testing would be favored.